Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris Pusilla in Brazil: Occurrence Away from the Coast and a New Record for the Central-West Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 27(3): 218–221. SHORT-COMMUNICARTICLEATION September 2019 Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla in Brazil: occurrence away from the coast and a new record for the central-west region Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira1,3 & Jayrson Araújo de Oliveira2 1 Programa Integrado de Estudos da Fauna da Região Centro Oeste do Brasil (FaunaCO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 March 2019. Accepted on 16 September 2019. ABSTRACT: The Semipalmated Sandpiper, Calidris pusilla, is a Western Hemisphere migrant shorebird for which Brazil forms an internationally important contranuptial area. In Brazil, the species main contranuptial areas is along the Atlantic Ocean coast, in the north and northeast regions. In addition to these primary contranuptial areas, there are also records of vagrants widely distributed across Brazil. Here, we review the occurrence of vagrants of this species in Brazil, and document a new record of C. pusilla for the central-west region and a first occurrence for the state of Goiás. KEY-WORDS: geographical distribution, Nearctic migrant, shorebird, state of Goiás, vagrant. The Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla (Linnaeus, of Mato Grosso (Cintra 2011, Levatich & Padilha 2019) 1766) is a migratory shorebird species that breeds in and two in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada Grosso do Sul (Serrano 2010, Tubelis & Tomas 2003). (Andres et al. 2012, IUCN 2019). Every year, as the However, there is no evidence that these records have northern autumn approaches, Arctic populations fly been correctly identified, as individuals appear not to from 3000 to 4000 km to South America (Hicklin & have been collected and sent to a scientific collection, nor Gratto-Trevor 2010). -

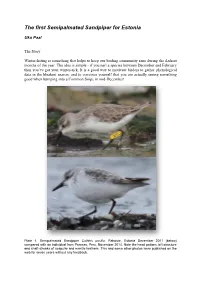

The First Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia

The first Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia Uku Paal The Story Winter-listing is something that helps to keep our birding community sane during the darkest months of the year. The idea is simple - if you nail a species between December and February then you’ve got your winter-tick. It is a good way to motivate birders to gather phenological data in the bleakest season, and to convince yourself that you are actually seeing something good when bumping into a Common Snipe in mid-December! Plate 1. Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. Rahuste, Estonia December 2011 (below) compared with an individual from Paracas, Peru, November 2014. Note the head pattern, bill structure and shaft-streaks of scapular and mantle feathers. This and some other photos were published on the web for seven years without any feedback. The late autumn of 2011 looked perfect to get some lingering migrants, as the warm weather was going strong well into January. In the first few days of December, I usually try to get to the west coast in the hope of some lost migrants, and so I packed myself off with Mari and Margus and headed to Saaremaa. Coastal meadows here are often hold a good selection of birds... We start at Türju lighthouse on the 3rd of December with a seawatching session. Nothing shocking this time with the usual Red-throated Divers, Razorbills, and a lone Red-necked Grebe passing. Rahuste coastal meadow is obviously the next site – a well-known place for getting some late birds. The situation looks exceptionally good. After trampling the area for couple of hours we manage to find White Wagtail, Skylark, five Common Snipe, two Pintail, 15 Lapwing, two Common Redshank, Grey Plover and Brant Goose among many other birds. -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

Field Checklist (PDF)

Surf Scoter Marbled Godwit OWLS (Strigidae) Common Raven White-winged Scoter Ruddy Turnstone Eastern Screech Owl CHICKADEES (Paridae) Common Goldeneye Red Knot Great Horned Owl Black-capped Chickadee Barrow’s Goldeneye Sanderling Snowy Owl Boreal Chickadee Bufflehead Semipalmated Sandpiper Northern Hawk-Owl Tufted Titmouse Hooded Merganser Western Sandpiper Barred Owl NUTHATCHES (Sittidae) Common Merganser Least Sandpiper Great Gray Owl Red-breasted Nuthatch Red-breasted Merganser White-rumped Sandpiper Long-eared Owl White-breasted Nuthatch Ruddy Duck Baird’s Sandpiper Short-eared Owl CREEPERS (Certhiidae) VULTURES (Cathartidae) Pectoral Sandpiper Northern Saw-Whet Owl Brown Creeper Turkey Vulture Purple Sandpiper NIGHTJARS (Caprimulgidae) WRENS (Troglodytidae) HAWKS & EAGLES (Accipitridae) Dunlin Common Nighthawk Carolina Wren Osprey Stilt Sandpiper Whip-poor-will House Wren Bald Eagle Buff-breasted Sandpiper SWIFTS (Apodidae) Winter Wren Northern Harrier Ruff Chimney Swift Marsh Wren Sharp-shinned Hawk Short-billed Dowitcher HUMMINGBIRDS (Trochilidae) THRUSHES (Muscicapidae) Cooper’s Hawk Wilson’s Snipe Ruby-throated Hummingbird Golden-crowned Kinglet Northern Goshawk American Woodcock KINGFISHERS (Alcedinidae) Ruby-crowned Kinglet Red-shouldered Hawk Wilson’s Phalarope Belted Kingfisher Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Broad-winged Hawk Red-necked Phalarope WOODPECKERS (Picidae) Eastern Bluebird Red-tailed Hawk Red Phalarope Red-headed Woodpecker Veery Rough-legged Hawk GULLS & TERNS (Laridae) Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Gray-cheeked Thrush Golden -

Least Sandpiper (Calidris Minutilla) Breeding in Massachusetts

Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla breeding in Massachusetts A breedingrange extension southwestward of 480 kilometers; thefirst known UnitedStates breeding record Kathleen S. Anderson HELEAST SANDPIPER (Calidris minu- firreed as a Calidris minutilla chick ap- Clement (1961) reported a brood of tilla) breedsfrom subarcticAlaska proximately 3 days old (Jehl, pers. Least Sandpiper chicks as early as June to Newfoundland, with Cape Sable Is- comm.). The specimenhas been donated 11 at Cape Sable Island. Miller (1977) •n- land and Sable Island, Nova Scotia the to the Museum of Comparative Zoology dicated that clutchesare completed from southernmost limits of the reported at Harvard University. May 23 to June 24 which, given 14-17 breedingrange (Godfrey 1966:155).Re- Monomoy Island is a typical Atlantic days for incubation (Jehl, 1970) would cent seasonal reports from American barrier beach of sand dunes and marsh mean young hatch between June 6 and Btrds(Finch 1971, 1975),indicate an in- extending in a north-south direction July 11 at that location. creasein breeding recordsfrom coastal from the elbow of Cape Cod at I thank Richard A. Harlow and Tabor Halifax County, Nova Scotia, but this Chatham. Once a peninsula,Monomoy Academy for providing transportanon may representintensified search rather recently (c. 1959) became an island to Monomoy Island, Brian A. Harr- than a population change (McLaren, about 16km long. On February 8, 1978, ington for his editorial help, and pers.comm.). Reportsfrom New Bruns- a severestorm causeda cut through the William H. Drury, Jr., for suggesting•n- wick do not suggest breeding there middle of the island dividing it into two stantly the probable identification from (Christie, pers. -

British Birds |

VOL. LU JULY No. 7 1959 BRITISH BIRDS WADER MIGRATION IN NORTH AMERICA AND ITS RELATION TO TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS By I. C. T. NISBET IT IS NOW generally accepted that the American waders which occur each autumn in western Europe have crossed the Atlantic unaided, in many (if not most) cases without stopping on the way. Yet we are far from being able to answer all the questions which are posed by these remarkable long-distance flights. Why, for example, do some species cross the Atlantic much more frequently than others? Why are a few birds recorded each year, and not many more, or many less? What factors determine the dates on which they cross? Why are most of the occurrences in the autumn? Why, despite the great advantage given to them by the prevail ing winds, are American waders only a little more numerous in Europe than European waders in North America? To dismiss the birds as "accidental vagrants", or to relate their occurrence to weather patterns, as have been attempted in the past, may answer some of these questions, but render the others still more acute. One fruitful approach to these problems is to compare the frequency of the various species in Europe with their abundance, migratory behaviour and ecology in North America. If the likelihood of occurrence in Europe should prove to be correlated with some particular type of migration pattern in North America this would offer an important clue as to the causes of trans atlantic vagrancy. In this paper some aspects of wader migration in North America will be discussed from this viewpoint. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America. -

The Occurrence and Identification of Red-Necked Stint in British Columbia Rick Toochin (Revised: December 3, 2013)

The Occurrence and Identification of Red-necked Stint in British Columbia Rick Toochin (Revised: December 3, 2013) Introduction The first confirmed report of a Red-necked Stint (Calidris ruficollis) in British Columbia was an adult in full breeding plumage found on June 24, 1978 at Iona Island (see Table 1, confirmed records item 1). Recently another older sighting has been uncovered that fits the timing of occurrence for this species in BC and may be valid (see Table 2, hypothetical records item 1). Since the first initial sightings in the late 1970s, there has been a slow but steady increase in observations of this beautiful Asian shorebird in British Columbia and, indeed, across the whole of North America. With an increase in both observer coverage and the knowledge of observers, this species is now known to be of regular, and probably annual, occurrence during fall migration in coastal British Columbia. Additionally, this species is now recorded occasionally during spring migration, indicating that at least a few individuals may be successfully wintering farther south in the western hemisphere. Identification of this species is straightforward when presented with a full breeding- plumaged adult, but identification of birds in juvenile and faded breeding plumage can be very complicated due to the close similarities to other small Calidris shorebirds. This paper describes the distribution and occurrence of the species in B.C., and also examines the similarities of all plumages of Red-necked Stint to species with which it might be confused, most notably Little Stint (C. minuta), Semipalmated Sandpiper (C. pusilla), and Western Sandpiper (C. -

Seven Deadly Stints and Their Friends an Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L

Seven Deadly Stints and their Friends An Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L. Dunn Larry Sansone photos 13 October 2020 Los Angeles Birders Genus Calidris – Composed of 23 species the largest genus within the large family (94 species worldwide, 66 in North America) of Scolopacidae (Sandpipers). – All 23 species in the genus Calidris have been found in North America, 19 of which have occurred in California. – Only Great Knot, Broad-billed Sandpiper, Temminck’s Stint, and Spoon-billed Sandpiper have not been recorded in the state, and as for Great Knot, well half of one turned up! Genus Calidris – The genus was described by Marrem in 1804 (type by tautonymy, Red Knot, 1758 Linnaeus). – Until 1934, the genus was composed only of the Red Knot and Great Knot. – This genus is composed of small to moderate sized sandpipers and use a variety of foraging styles from probing in water to picking at the shore’s edge, or even away from water on mud or the vegetated border of the mud. – As within so many families or large genre behavior offers important clues to species identification. Genus Calidris – Most, but not all, species migrate south in their alternate (breeding) or juvenal plumage, molting largely once they reach their more southerly wintering grounds. – Most species nest in the arctic, some farther north than others. Some species breed primarily in Eurasia, some in North America. Some are Holarctic. – The majority of species are monotypic (no additional recognized subspecies). Genus Calidris – In learning these species one