British Birds |

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris Pusilla in Brazil: Occurrence Away from the Coast and a New Record for the Central-West Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 27(3): 218–221. SHORT-COMMUNICARTICLEATION September 2019 Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla in Brazil: occurrence away from the coast and a new record for the central-west region Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira1,3 & Jayrson Araújo de Oliveira2 1 Programa Integrado de Estudos da Fauna da Região Centro Oeste do Brasil (FaunaCO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 March 2019. Accepted on 16 September 2019. ABSTRACT: The Semipalmated Sandpiper, Calidris pusilla, is a Western Hemisphere migrant shorebird for which Brazil forms an internationally important contranuptial area. In Brazil, the species main contranuptial areas is along the Atlantic Ocean coast, in the north and northeast regions. In addition to these primary contranuptial areas, there are also records of vagrants widely distributed across Brazil. Here, we review the occurrence of vagrants of this species in Brazil, and document a new record of C. pusilla for the central-west region and a first occurrence for the state of Goiás. KEY-WORDS: geographical distribution, Nearctic migrant, shorebird, state of Goiás, vagrant. The Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla (Linnaeus, of Mato Grosso (Cintra 2011, Levatich & Padilha 2019) 1766) is a migratory shorebird species that breeds in and two in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada Grosso do Sul (Serrano 2010, Tubelis & Tomas 2003). (Andres et al. 2012, IUCN 2019). Every year, as the However, there is no evidence that these records have northern autumn approaches, Arctic populations fly been correctly identified, as individuals appear not to from 3000 to 4000 km to South America (Hicklin & have been collected and sent to a scientific collection, nor Gratto-Trevor 2010). -

Studies of the Foods and Feeding Ecology of Wading Birds

STUDIES OF THE FOODS AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF WADING BIRDS Thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Council for National Academic Awards .. by Malcolm E. Greenhalgh, B. A. Department of Biology Liverpool Polytechnic October 1975 s ABSTRACT In this thesis are described the populations of waders (Aves: Charadrii) occurring on the Ribble Estuary, Lancashire, special reference being made to the eleven species comprising the bulk of the shore wader population. The daily routine of these birds is described including the time spent in feeding. The feeding areas are described together with the foods taken from gut and pellet analysis and direct observation. The distributions of invertebrates, and especially those of major importance as wader food, are described as well as the factors affecting these distributions. Variations in density of prey in relation to O. D., general geography of the estuary, and time of year are included. Depth distribution and variations in prey size are outlined for the main species. Food intake was studied in the eight main waders. Daily intake through the year is described. in relation to energy requirements. Variations of feeding rates with several factors are included. All data are combined to enable calculation of the total biomasses of the main prey taken by waders in the course of a year. These are compared with total minimum annual production of the prey. Future work, including a computer study based on these and extra data, is outlined. Frontispiece a. The author counting a flock of 45,000 Knot 25 August, 1972 b. -

Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Field identification of smaller sandpipers within the genus C/dr/s Richard R. Veit and Lars Jonsson Paintings and line drawings by Lars Jonsson INTRODUCTION the hand, we recommend that the reader threeNearctic species, the Semipalmated refer to the speciesaccounts of Prateret Sandpiper (C. pusilia), the Western HESMALL Calidris sandpipers, affec- al. (1977) or Cramp and Simmons Sandpiper(C. mauri) andthe LeastSand- tionatelyreferred to as "peeps" in (1983). Our conclusionsin this paperare piper (C. minutilla), and four Palearctic North America, and as "stints" in Britain, basedupon our own extensivefield expe- species,the primarilywestern Little Stint haveprovided notoriously thorny identi- rience,which, betweenus, includesfirst- (C. minuta), the easternRufous-necked ficationproblems for many years. The hand familiarity with all sevenspecies. Stint (C. ruficollis), the eastern Long- first comprehensiveefforts to elucidate We also examined specimensin the toed Stint (C. subminuta)and the wide- thepicture were two paperspublished in AmericanMuseum of Natural History, spread Temminck's Stint (C. tem- Brtttsh Birds (Wallace 1974, 1979) in Museumof ComparativeZoology, Los minckii).Four of thesespecies, pusilla, whichthe problem was approached from Angeles County Museum, San Diego mauri, minuta and ruficollis, breed on the Britishperspective of distinguishing Natural History Museum, Louisiana arctictundra and are found during migra- vagrant Nearctic or eastern Palearctic State UniversityMuseum of Zoology, tion in flocksof up to thousandsof -

Black Oystercatcher

Alaska Species Ranking System - Black Oystercatcher Black Oystercatcher Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Haematopus bachmani Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 08 April 2019 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: Species of Greatest Conservation Need IUCN: Audubon AK: S Rank: S2S3B,S2 USFWS: Bird of Conservation Concern BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 11 Action -40 to 40 -4 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Suspected stable (ASG 2019; Cushing et al. 2018), but data are limited and do not encompass this species' entire range. We therefore rank this question as Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Habitat is dynamic and subject to change as a result of geomorphic and glacial processes. For example, numbers expanded on Middleton Island after the 1964 earthquake (Gill et al. 2004). Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -2 Uncertain. The global population is estimated at 11,000 individuals, of which 45%-70% breed in Alaska (ASG 2019). -

Solitary Sandpipers Nesting in Montana

Solitary Sandpipers Breeding in Montana Progress Report for the 2020 Field Season and Summary of Past Work Montana Bird Advocacy, Missoula, Montana 2 March 2021 Most Solitary Sandpipers (Tringa solitaria) breed in Alaska and Canada near wetlands surrounded by boreal forest habitat. They were first confirmed breeding in the contiguous United States in northern Minnesota in 1973 (Savoloja 1973). Additional nesting attempts (dependent young, not nests with eggs) were documented annually in Minnesota from 1982–1984 and in 1987, 2012, and 2013 (Hoffman and Hoffman 1982, Pfannmuller et al. 2017). Solitary Sandpipers were strongly suspected to have nested in Oregon several times between 1981 and 1995 (Sawyer 1981, Lundsten 1996), but no nest or dependent young were observed. The species had never been documented nesting in Montana prior to our work in 2018 (Marks et al. 2016). Recent observations from Glacier National Park (GNP) suggested that they bred in the state. Single adults were observed at two wetlands during the summer of 2007 and at a third location in 2010, 2011, and 2016 (see Tables 1 & 2) as they vocalized and perched in trees, which are typical behaviors of breeding birds but not of migrants (Paulson 1993). These three sites were on the west side of the park. Also, birds that may have been territorial were seen at two unnamed lakes near the eastern boundary of the park in June and July of 2013 (Steve Gniadek, pers. comm.). Habitat at these sites is similar to that at breeding sites in Canada. We documented the first nesting attempt known for Solitary Sandpipers in Montana in 2018 at Sondreson Meadow just outside the boundary of GNP (Fig. -

The First Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia

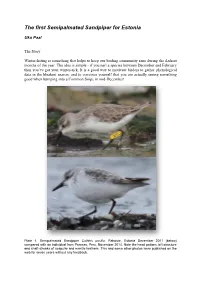

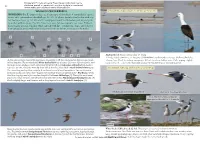

The first Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia Uku Paal The Story Winter-listing is something that helps to keep our birding community sane during the darkest months of the year. The idea is simple - if you nail a species between December and February then you’ve got your winter-tick. It is a good way to motivate birders to gather phenological data in the bleakest season, and to convince yourself that you are actually seeing something good when bumping into a Common Snipe in mid-December! Plate 1. Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. Rahuste, Estonia December 2011 (below) compared with an individual from Paracas, Peru, November 2014. Note the head pattern, bill structure and shaft-streaks of scapular and mantle feathers. This and some other photos were published on the web for seven years without any feedback. The late autumn of 2011 looked perfect to get some lingering migrants, as the warm weather was going strong well into January. In the first few days of December, I usually try to get to the west coast in the hope of some lost migrants, and so I packed myself off with Mari and Margus and headed to Saaremaa. Coastal meadows here are often hold a good selection of birds... We start at Türju lighthouse on the 3rd of December with a seawatching session. Nothing shocking this time with the usual Red-throated Divers, Razorbills, and a lone Red-necked Grebe passing. Rahuste coastal meadow is obviously the next site – a well-known place for getting some late birds. The situation looks exceptionally good. After trampling the area for couple of hours we manage to find White Wagtail, Skylark, five Common Snipe, two Pintail, 15 Lapwing, two Common Redshank, Grey Plover and Brant Goose among many other birds. -

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds

CHAPTER 1 General introduction 1.1 Shorebirds in Australia Shorebirds, sometimes referred to as waders, are birds that rely on coastal beaches, shorelines, estuaries and mudflats, or inland lakes, lagoons and the like for part of, and in some cases all of, their daily and annual requirements, i.e. food and shelter, breeding habitat. They are of the suborder Charadrii and include the curlews, snipe, plovers, sandpipers, stilts, oystercatchers and a number of other species, making up a diverse group of birds. Within Australia, shorebirds account for 10% of all bird species (Lane 1987) and in New South Wales (NSW), this figure increases marginally to 11% (Smith 1991). Of these shorebirds, 45% rely exclusively on coastal habitat (Smith 1991). The majority, however, are either migratory or vagrant species, leaving only five resident species that will permanently inhabit coastal shorelines/beaches within Australia. Australian resident shorebirds include the Beach Stone-curlew (Esacus neglectus), Hooded Plover (Charadrius rubricollis), Red- capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus), Australian Pied Oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris) and Sooty Oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus) (Smith 1991, Priest et al. 2002). These species are generally classified as ‘beach-nesting’, nesting on sandy ocean beaches, sand spits and sand islands within estuaries. However, the Sooty Oystercatcher is an island-nesting species, using rocky shores of near- and offshore islands rather than sandy beaches. The plovers may also nest by inland salt lakes. Shorebirds around the globe have become increasingly threatened with the pressure of predation, competition, human encroachment and disturbance and global warming. Populations of birds breeding in coastal areas which also support a burgeoning human population are under the highest threat. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

OSNZ News Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the Members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.)

Supplement to Notornis, Vol. 25, Part 3, September 1978 OSNZ news Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.). No. 8 September 1978 NOTE: Next deadline is earlier to try to beat the Christmas and January shut- Deadline for the December issue will be down of printers and have NOTORNIS 20 November. and OSNZ NEWS out early in 1979. DACHICKS Rough estimates: northland 150-200; The 1978 inquiry into the NZ Dabchick has gone remarkably well, with North Island Volcanic Plateau 600-800; South Taranakii members putting in a lot of time, often with meagre results, in order to help form an overall Wanganui 30; ManawatulWairarapa 300; picture of the status and habits of this species. GisborneiHawkes Bay 50. Total 1 150-1400. We began with a series of questions, to which we now have much better answers. If We thus already have a fairly good base members can stand it, we need another year's effort to confirm and clarify these answers. line agalnst which to measure any major changes in the future. Another year's f~eld 1. Is the NZ Dabchick extinct in the South Island? Answer, apparently yes. Was it ever work should cons~derably Improve the strong there? Possibly not (see Oliver). accuracy of our knowledge. 2. Does the North Island population reach a total of 1000? Answer, yes. Est~matedtotal Regional activity (very rough, see below) 1 1 50-1400 birds. We have no up-tb-date report from Far 3. Are Australian grebelets taking over? Answer, in North Island, not yet. -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3).