Solitary Sandpipers Nesting in Montana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

Tringarefs V1.3.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2016 & 2017 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and best employed in conjunction with other reference sources. Grateful thanks to Graham Clarke (http://grahamsphoto.blogspot.com/) and Tom Shevlin (www.wildlifesnaps.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds). 2016. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 6.1 accessed February 2016]). Version Version 1.3 (March 2016). Cover Main image: Spotted Redshank. Albufera, Mallorca. 13th April 2011. Picture by Graham Clarke. Vignette: Solitary Sandpiper. Central Bog, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 29th August 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Species Page No. Greater Yellowlegs [Tringa melanoleuca] 14 Green Sandpiper [Tringa ochropus] 16 Greenshank [Tringa nebularia] 11 Grey-tailed Tattler [Tringa brevipes] 20 Lesser Yellowlegs [Tringa flavipes] 15 Marsh Sandpiper [Tringa stagnatilis] 10 Nordmann's Greenshank [Tringa guttifer] 13 Redshank [Tringa totanus] 7 Solitary Sandpiper [Tringa solitaria] 17 Spotted Redshank [Tringa erythropus] 5 Wandering Tattler [Tringa incana] 21 Willet [Tringa semipalmata] 22 Wood Sandpiper [Tringa glareola] 18 1 Relevant Publications Bahr, N. 2011. The Bird Species / Die Vogelarten: systematics of the bird species and subspecies of the world. Volume 1: Charadriiformes. Media Nutur, Minden. Balmer, D. et al 2013. Bird Atlas 2001-11: The breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. -

Fall 2009 Vol. 28 No. 3

V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2009 Vol. 28, No. 3 V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 3 Fall 2009 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Western Kingbird by Leonard Medlock, 11/17/09, at the Rochester wastewater treatment plant, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2010 www.nhbirdrecords.org Published by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department Printed on Recycled Paper V28 No3 Fall09_final 5/19/10 8:41 AM Page 1 IN MEMORY OF Tudor Richards We continue to honor Tudor Richards with this third of the four 2009 New Hampshire Bird Records issues in his memory. -

Green Sandpiper

Green Sandpiper The Green Sandpiper (Tringa ochropus) is a small wader of the Old World. The genus name Tringa is the New Latin name given to the Green Sandpiper by Aldrovandus in 1599 based on Ancient Greek trungas, a thrush-sized, white- rumped, tail-bobbing wading bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific ochropus is from Ancient Greek okhros, "ochre", and pous, "foot". The Green Sandpiper represents an ancient lineage of the genus Tringa and its only close living relative is the Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria). They both have brown wings with little light dots and a delicate but contrasting neck and chest pattern. In addition, both species nest in trees, unlike most other scolopacids. Given its basal position in Tringa, it is fairly unsurprising that suspected cases of hybridisation between this species and the Common Sandpiper (A. hypoleucos) of the sister genus Actitis have been reported. This species is a somewhat plump wader with a dark greenish-brown back and wings, greyish head and breast and otherwise white underparts. The back is spotted white to varying extents, being maximal in the breeding adult, and less in winter and young birds. The legs and short bill are both dark green. It is conspicuous and characteristically patterned in flight, with the wings dark above and below and a brilliant white rump. The latter feature reliably distinguishes it from the slightly smaller but otherwise very similar Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria) of North America. It breeds across subarctic Europe and Asia and is a migratory bird, wintering in southern Europe, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and tropical Africa. -

Vertebrate Diversity Benefiting from Carrion Provided by Pumas And

Biological Conservation 215 (2017) 123–131 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication Vertebrate diversity benefiting from carrion provided by pumas and other subordinate, apex felids MARK L. Mark Elbroch⁎, Connor O'Malley, Michelle Peziol, Howard B. Quigley Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Carrion promotes biodiversity and ecosystem stability, and large carnivores provide this resource throughout the Biodiversity year. In particular, apex felids subordinate to other carnivores contribute more carrion to ecological commu- Carnivores nities than other predators. We measured vertebrate scavenger diversity at puma (Puma concolor) kills in the Food webs Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and utilized a model-comparison approach to determine what variables influ- Scavenging enced scavenger diversity (Shannon's H) at carcasses. We documented the highest vertebrate scavenger diversity of any study to date (39 birds and mammals). Scavengers represented 10.9% of local birds and 28.3% of local mammals, emphasizing the diversity of food-web vectors supported by pumas, and the positive contributions of pumas and potentially other subordinate, apex felids to ecological stability. Scavenger diversity at carcasses was most influenced by the length of time the carcass was sampled, and the biological variables, temperature and prey weight. Nevertheless, diversity was relatively consistent across carcasses. We also identified six additional stalk- and-ambush carnivores weighing > 20 kg, that feed on prey larger than themselves, and are subordinate to other predators. Together with pumas, these seven felids may provide distinctive ecological functions through their disproportionate production of carrion and subsequent contributions to biodiversity. -

British Birds |

VOL. LU JULY No. 7 1959 BRITISH BIRDS WADER MIGRATION IN NORTH AMERICA AND ITS RELATION TO TRANSATLANTIC CROSSINGS By I. C. T. NISBET IT IS NOW generally accepted that the American waders which occur each autumn in western Europe have crossed the Atlantic unaided, in many (if not most) cases without stopping on the way. Yet we are far from being able to answer all the questions which are posed by these remarkable long-distance flights. Why, for example, do some species cross the Atlantic much more frequently than others? Why are a few birds recorded each year, and not many more, or many less? What factors determine the dates on which they cross? Why are most of the occurrences in the autumn? Why, despite the great advantage given to them by the prevail ing winds, are American waders only a little more numerous in Europe than European waders in North America? To dismiss the birds as "accidental vagrants", or to relate their occurrence to weather patterns, as have been attempted in the past, may answer some of these questions, but render the others still more acute. One fruitful approach to these problems is to compare the frequency of the various species in Europe with their abundance, migratory behaviour and ecology in North America. If the likelihood of occurrence in Europe should prove to be correlated with some particular type of migration pattern in North America this would offer an important clue as to the causes of trans atlantic vagrancy. In this paper some aspects of wader migration in North America will be discussed from this viewpoint. -

Solitary Sandpiper Early Reproductive Behavior •

SOLITARY SANDPIPER EARLY REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOR • LEWIS W. ORING THE Solitary Sandpiper (Tringa solitaria) is among the least known of Nearctic birds, primarily becauseof its inaccessibilityduring the breeding season. The speciesnests about muskeg and woodland pools using old nests of such passeriformspecies as the Rusty Blackbird (Euphaguscarolinus), Robin (Turdus migratorius), Common Grackle (Quiscalus quiscula), Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla ce•orum), Bo- hemianWaxwing ( B. garrulus) , Eastern Kingbird ( Tyrannustyrannus ) , and Gray Jay (Perisoreuscanadensis). It is not known if they ever preemptnests, but at least occasionallythey use freshly made nests (D. F. Parmelee,pers. comm.). Eggs have been found from 1.2-12 m above the ground and from the shorelineto 200 m away, usually in conifers but sometimesin deciduoustrees (Henderson 1923, Street 1923, Bent, 1929, Sutton in Bannerman1958) and rarely (perhaps) in cattail (Todd 1963). T. solitaria is also known to be solitary and, perhaps,territorial year-round; and does not migrate in flocks as do most waders (Hudson 1920, Todd and Carriker 1922, Wetmore 1926, Sutton in Bannerman 1958). This unique combinationof solitary and arboreal habits makes solitaria of special interest, and the paucity of information concerning Solitary Sandpiperbehavior leads me to present my data despite their preliminarynature. I publisheddata on acousticalbehavior separately (Oring, 1968). STUDY AREA AI•ID METttODS I studied Solitary Sandpipers from 15-26 May 1968 at Crimson Lake Provincial Park, 12 km northwest of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada. The area was characterized by fens of black spruce (Picea mariana) separated longitudinally by sandy ridges covered with quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). Many of the muskegsor fens contained one or more deep ponds about which Solitary Sandpipers bred in the stunted spruce trees. -

54971 GPNC Shorebirds

A P ocket Guide to Great Plains Shorebirds Third Edition I I I By Suzanne Fellows & Bob Gress Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, The Nature Conservancy, and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Identification Tips • 4 Plovers I Black-bellied Plover • 6 I American Golden-Plover • 8 I Snowy Plover • 10 I Semipalmated Plover • 12 I Piping Plover • 14 ©Bob Gress I Killdeer • 16 I Mountain Plover • 18 Stilts & Avocets I Black-necked Stilt • 19 I American Avocet • 20 Hudsonian Godwit Sandpipers I Spotted Sandpiper • 22 ©Bob Gress I Solitary Sandpiper • 24 I Greater Yellowlegs • 26 I Willet • 28 I Lesser Yellowlegs • 30 I Upland Sandpiper • 32 Black-necked Stilt I Whimbrel • 33 Cover Photo: I Long-billed Curlew • 34 Wilson‘s Phalarope I Hudsonian Godwit • 36 ©Bob Gress I Marbled Godwit • 38 I Ruddy Turnstone • 40 I Red Knot • 42 I Sanderling • 44 I Semipalmated Sandpiper • 46 I Western Sandpiper • 47 I Least Sandpiper • 48 I White-rumped Sandpiper • 49 I Baird’s Sandpiper • 50 ©Bob Gress I Pectoral Sandpiper • 51 I Dunlin • 52 I Stilt Sandpiper • 54 I Buff-breasted Sandpiper • 56 I Short-billed Dowitcher • 57 Western Sandpiper I Long-billed Dowitcher • 58 I Wilson’s Snipe • 60 I American Woodcock • 61 I Wilson’s Phalarope • 62 I Red-necked Phalarope • 64 I Red Phalarope • 65 • Rare Great Plains Shorebirds • 66 • Acknowledgements • 67 • Pocket Guides • 68 Supercilium Median crown Stripe eye Ring Nape Lores upper Mandible Postocular Stripe ear coverts Hind Neck Lower Mandible ©Dan Kilby 1 Introduction Shorebirds, such as plovers and sandpipers, are a captivating group of birds primarily adapted to live in open areas such as shorelines, wetlands and grasslands. -

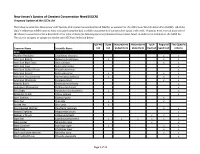

NJ List of Species of Greatest Conservation Need

New Jersey's Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Proposed Update of the SGCN List The following table lists New Jersey's 657 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), as updated for the 2015 State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). All of the state's indigenous wildlife species were evaluated using the best available assessments of conservation status and trends. A species must meet at least one of the chosen assessment criteria described in the table, Criteria for Selecting Species of Greatest Conservation Need , in order to be included on the SGCN list. The criteria category or categories met by each SGCN are indicated below. USFWS State NatureServe NatureServe IUCN Regional Taxa Specific Common Name Scientific Name List List Global Rank State Rank Red List SGCN List Criteria Birds Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens x x American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus x x x American Black Duck Anas rubripes x x American Coot Fulica americana x American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica x American Kestrel Falco sparverius x x x American Oystercatcher Haematopus palliatus x x x American Woodcock Scolopax minor x x Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla hrota x Audubon's Shearwater Puffinus iherminieri x Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus x x Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula x Bank Swallow Riparia riparia x Barn Owl Tyto alba x x Barred Owl Strix varia x Bay-breasted Warbler Dendroica castanea x x Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon x Bicknell's Thrush Catharus bicknelli x x x Black Rail Laterallus jamaicensis x x x x x x Black Scoter Melanitta -

Characteristics and Status of the Solitary Sandpiper in Utah

May, 1957 203 CHARACTERISTICS AND STATUS OF THE SOLITARY SANDPIPER IN UTAH By RICHARD D. PORTER and JOHN B. BUSHMAN When Woodbury, Cottam, and Sugden (1949) compiled their check-list of the birds of Utah, only two specimens of the Solitary Sandpiper (Tvinga soldaria) were known from the state and both were assigned to the race T. s. cinnamomea. One (UUMZ 5075), collected on July 9, 1937, two miles southwest of Poncho House, San Juan County, was reported by Woodbury and Russell (1945:48). The other was reported by Twomey ( 1942 :392) and was taken at the Ashley Creek marshes, two miles south of Jensen in Uintah County. This latter has not been examined by US. Behle and Selander (1952: 26-27) reported two additional specimens from Ibapah, Tooele County (UUMZ 10719)) and Farmington Bay, Davis County (UUMZ 10984). They also studied the specimen (UUMZ 5075) reported by Woodbury and Russell (Zoc. cit.), as well as a specimen (UUMZ 4142) from Navajo County, Arizona (Wood- bury and Russell, Zoc. cit.). All of these were referred to the race T. s. so&aria. Since Twomey (Zoc. cit.) had reported that the Ashley Creek birds remained as residents and were paired and doubtless nested, even though the nests were not located, Behle and Selander felt that they too should be referred to T. s. so&aria. Hellmayr and Conover ( 1948: 119-I 2 1) give the breeding range of T. s. cinnamomea as northern Canada from the tree limit south to about 60’ north latitude and from the Bering Sea to the west coast of Hudson Bay. -

Shorebird Habitat Conservation Strategy

Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes Region Joint Venture Shorebird Habitat Conservation Strategy May 2007 1 Shorebird Strategy Committee and Members of the Joint Venture Science Team Bob Gates, Ohio State University, Chair Dave Ewert, The Nature Conservancy Diane Granfors, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bob Russell, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bradly Potter, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mark Shieldcastle, Ohio Department of Natural Resources Greg Soulliere, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Cover: Long-billed Dowitcher. Photo by Gary Kramer. i Table of Contents Plan Summary................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements...................................................................................................... 2 Background and Context ................................................................................................. 3 Population Status and Trends ......................................................................................... 6 Habitat Characteristics .................................................................................................. 11 Biological Foundation..................................................................................................... 14 Planning Framework.................................................................................................. 14 Migration and Distribution........................................................................................ 15 Limiting