Migratory Birds Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF/36 2/36 2 175-181.Pdf Stenhouse

VOLUME 15, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 11 D'Entremont, K. J. N., L. Minich Zitske, A. J. Gladwell, N. K. Elliott, R. A. Mauck, and R. A. Ronconi. 2020. Breeding population decline and associations with nest site use of Leach’s Storm-Petrels on Kent Island, New Brunswick from 2001 to 2018. Avian Conservation and Ecology 15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01526-150111 Copyright © 2020 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Breeding population decline and associations with nest site use of Leach’s Storm-Petrels on Kent Island, New Brunswick from 2001 to 2018 Kyle J. N. d'Entremont 1,2, Laura Minich Zitske 3,4, Alison J. Gladwell 1, Nathan K. Elliott 3,5, Robert A. Mauck 6 and Robert A. Ronconi 7,8 1Dalhousie University, Canada, 2Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada, 3Bowdoin College, USA, 4Maine Audubon, USA, 5Point Blue Conservation Science, USA, 6Kenyon College, USA, 7Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 8Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada ABSTRACT. Leach’s Storm-Petrels (Hydrobates leucorhous) are burrow-nesting seabirds that breed on coastal islands throughout much of the North Atlantic, with most of the world’s population breeding in Atlantic Canada. Population declines in the past 20–30 years have resulted in the species being uplisted to “Vulnerable” on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. One of the species’ most well-studied colonies is on Kent Island, New Brunswick in the Bay of Fundy. -

Puffinus Gravis (Great Shearwater)

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Puffinus gravis (Great Shearwater) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Procellariiformes (Tubenoses) Family: Procellariidae (Fulmers, Petrels, And Shearwaters) General comments: Status seems secure though limited data Species Conservation Range Maps for Great Shearwater: Town Map: Puffinus gravis_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Puffinus gravis_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: North American Waterbird Conservation Plan: High Concern United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Great Shearwater: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Rocky Coast Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Pelagic (Water Column) Habitat System Name: Offshore **Primary Habitat** Stressors Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Stressors Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Species Specific Conservation Actions Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Guild Level Conservation Actions: This Species is currently not attributed to a guild. -

Beidaihe^ China: East Asian Hotspot Paul I

Beidaihe^ China: East Asian hotspot Paul I. Holt, Graham P. Catley and David Tipling China has come a long way since 1958 when 'Sparrows [probably meaning any passerine], rats, bugs and flies' were proscribed as pests and a war declared on them. The extermination of a reputed 800,000 birds over three days in Beijing alone was apparently then followed by a plague of insects (Boswall 1986). After years of isolation and intellectual stagnation during the Cultural Revolution, China opened its doors to organised foreign tour groups in the late 1970s and to individual travellers from 1979 onwards. Whilst these initial 'pion eering' travellers included only a handful of birdwatchers, news of the country's ornithological riches soon spread and others were quick to follow. With a national avifauna in excess of 1,200 species, the People's Republic offers vast scope for study. Many of the species are endemic or nearly so, a majority are poorly known and a few possess an almost mythical draw for European birders. Sadly, all too many of the endemic forms are either rare or endangered. Initially, most of the recent visits by birders were via Hong Kong, and concentrated on China's mountainous southern and western regions. Inevitably, however, attention has shifted towards the coastal migration sites. Migration at one such, Beidaihe in Hebei Province, in Northeast China, had been studied and documented by a Danish scientist during the Second World War (Hemmingsen 1951; Hemmingsen & Guildal 1968). It became the focus of renewed interest after a 1985 Cambridge University expedition (Williams et al. -

The Taxonomy of the Procellariiformes Has Been Proposed from Various Approaches

山 階 鳥 研 報(J. Yamashina Inst. Ornithol.),22:114-23,1990 Genetic Divergence and Relationships in Fifteen Species of Procellariiformes Nagahisa Kuroda*, Ryozo Kakizawa* and Masayoshi Watada** Abstract The genetic analysis of 23 protein loci in 15 species of Procellariiformes was made The genetic distancesbetween the specieswas calculatedand a dendrogram was formulated of the group. The separation of Hydrobatidae from all other taxa including Diomedeidae agrees with other precedent works. The resultsof the present study support the basic Procellariidclassification system. However, two points stillneed further study. The firstpoint is that Fulmarus diverged earlier from the Procellariidsthan did the Diomedeidae. The second point is the position of Puffinuspacificus which appears more closely related to the Pterodroma petrels than to other Puffinus species. These points are discussed. Introduction The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes has been proposed from various approaches. The earliest study by Forbes (1882) was made by appendicular myology. Godman (1906) and Loomis (1918) studied this group from a morphological point of view. The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes by functional osteology and appendicular myology was studied by Kuroda (1954, 1983) and Klemm (1969), The results of the various studies agreed in proposing four families of Procellariiformes: Diomedeidae, Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae, and Pelecanoididae. They also pointed out that the Procellariidae was a heterogenous group among them. Timmermann (1958) found the parallel evolution of mallophaga and their hosts in Procellariiformes. Recently, electrophoretical studies have been made on the Procellariiformes. Harper (1978) found different patterns of the electromorph among the families. Bar- rowclough et al. (1981) studied genetic differentiation among 12 species of Procellari- iformes at 16 loci, and discussed the genetic distances among the taxa but with no consideration of their phylogenetic relationships. -

Conservation Status of Birds of Prey and Owls in Norway

Conservation status of birds of prey and owls in Norway Oddvar Heggøy & Ingar Jostein Øien Norsk Ornitologisk Forening 2014 NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 © NOF-BirdLife Norway E-mail: [email protected] Publication type: Digital document (pdf)/75 printed copies January 2014 Front cover: Boreal owl at breeding site in Nord-Trøndelag. © Ingar Jostein Øien Editor: Ingar Jostein Øien Recommended citation: Heggøy, O. & Øien, I. J. (2014) Conservation status of birds of prey and owls in Norway. NOF/BirdLife Norway - Report 1-2014. 129 pp. ISSN: 0805-4932 ISBN: 978-82-78-52092-5 Some amendments and addenda have been made to this PDF document compared to the 75 printed copies: Page 25: Picture of snowy owl and photo caption added Page 27: Picture of white-tailed eagle and photo caption added Page 36: Picture of eagle owl and photo caption added Page 58: Table 4 - hen harrier - “Total population” corrected from 26-147 pairs to 26-137 pairs Page 60: Table 5 - northern goshawk –“Total population” corrected from 1434 – 2036 pairs to 1405 – 2036 pairs Page 80: Table 8 - Eurasian hobby - “Total population” corrected from 119-190 pairs to 142-190 pairs Page 85: Table 10 - peregrine falcon – Population estimate for Hedmark corrected from 6-7 pairs to 12-13 pairs and “Total population” corrected from 700-1017 pairs to 707-1023 pairs Page 78: Photo caption changed Page 87: Last paragraph under “Relevant studies” added. Table text increased NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 NOF-BirdLife Norway – Report 1-2014 SUMMARY Many of the migratory birds of prey species in the African-Eurasian region have undergone rapid long-term declines in recent years. -

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Pechora Pipitanthus Gustavi in Australia

59 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2003, 20, 59-65 Pechora PipitAnthus gustavi in Australia MIKE CARTER 30 Canadian Bay Road, Mount Eliza, Victoria 3930 (Email: [email protected]) Summary A Pechora Pipit Anthus gustavi was present on West Island, Ashmore Reef, off the northern coast of Western Australia on 4 and 5 November 2001. This paper documents the occurrence, the first record for Australia. lntrQduction During the morning of 4 November 2001, twelve observers (Allan Benson, Rob Benson, Peter Crabtree, Penny Drake-Brockman, Phil Joy, Chris Lester, Jann Mullholland, Ross Mullholland, Stuart Pell, Fred Smith, George Swann and the author) carried out a census of the birds of West Island, Ashmore Reef (12°14'S, 122°58'E). This is about 600 km north of Broome in Western Australia. Apart from the resident Buff-banded Rails Gallirallus philippensis, the only land birds discovered were passage migrants: 4 Oriental Cuckoos Cuculus saturatus, 1 Little Bronze-Cuckoo Chrysococcyx minutillus, 4 Sacred Kingfishers Todiramphus sanctus, 3 Rainbow Bee-eaters Merops omatus, 3 Magpie-larks Grallina cyanoleuca, 4 Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava and 2 Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica. In the late morning a small, short-tailed passerine was flushed but not identified. In the afternoon, a small ground-bird was seen walking into a clump ofArgusia argentia. This large sprawling shrub growing to about 5 m tall, with a dome-like canopy embraced by creeping vines, is confined almost completely to the fringes of the island where it is the dominant vegetation. In spite of a prolonged attempt, we were unable to identify the bird before nightfall, but the views obtained were sufficient to suggest that our quarry was a pipit Anthus sp. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

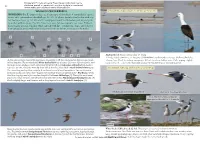

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Nesting Birds and Two Fox Species

BIODIVERSITY CHANGES AT THE INTERFACE OF MARINE AND TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEMS: Nesting birds and two fox species David R. Klein, University of Alaska Fairbanks, AK Heather Renner, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Homer, AK Richard Kleinleder, URS, Homer, AK Climate warming in the Arctic and Subarctic has brought about decline in the seasonal extent of sea ice, rising sea levels, accelerated coastal erosion, and changes in the distribution and biodiversity of species of mammals and birds. What are the consequences of these climate- induced changes for nesting birds and resident mammals at the ecosystem and species levels on the St. Matthew Islands? The St. Matthew Islands, now part of Alaska, were discovered during an exploration cruise by Lieutenant Synd of the Russian Navy in the mid-1760’s. Captain Cook “re-discovered” and named the islands in 1778. •In 1909, St. Matthew and adjacent islands were given protective status as a bird reserve by President Theodore Roosevelt, designated as the Bering Sea Reservation These islands attained “Wilderness” status within the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980 Several million sea birds, including >15 species, nest on the St. Matthew Islands, and walrus, sea lions, and seals haul out there Pinnacle Is. There are two vertebrate species endemic to these islands McKay’s bunting Plectrophenax hyperboreus Singing vole Microtus abreviatus Ian Jones photo The St. Mathew Islands are the nesting location for the major portion of the Bering Sea rock sandpiper population The St. Matthew Islands include 3 islands, the largest is about 52 km long, as the biologist walks, and averages ~6 km wide. -

Nov. 24Th – 7:00 Pm by Zoom Doors Will Open at 6:30

Wandering November 2020 Volume 70, Number 3 Tattler The Voice of SEA AND SAGE AUDUBON, an Orange County Chapter of the National Audubon Society Why Do Birders Count Birds? General Meeting - Online Presentation th Gail Richards, President Friday, November 20 – 7:00 PM Via Zoom Populations of birds are changing, both in the survival of each species and the numbers of birds within each “Motus – an exciting new method to track species. In California, there are 146 bird species that are vulnerable to extinction from climate change. These the movements of birds, bats, & insects” fluctuations may indicate shifts in climate, pollution levels, presented by Kristie Stein, MS habitat loss, scarcity of food, timing of migration or survival of offspring. Monitoring birds is an essential part of protecting them. But tracking the health of the world’s 10,000 bird species is an immense challenge. Scientists need thousands of people reporting what they are seeing in their back yards, neighborhoods, parks, nature preserves and in all accessible wild areas. Even though there are a number of things we are unable to do during this pandemic, Sea and Sage volunteers are committed to continuing bird surveys (when permitted, observing Covid-19 protocols). MONTHLY SURVEYS: Volunteers survey what is out there, tracking the number of species and their abundance. San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary UCI Marsh Kristie Stein is a Wildlife Biologist with the Southern University Hills Eco Reserve Sierra Research Station (SSRS) in Weldon, California. Upper Newport Bay by pontoon boat Her research interests include post-fledging ecology, seasonal interactions and carry-over effects, and SEASONAL SURVEYS AND/OR MONITORING: movement ecology. -

Supplementary Information

Supporting Information Balk et al. 10.1073/pnas.0902903106 Movie S1. A paralyzed herring gull (Larus argentatus). This movie shows a specimen from the County of So¨ dermanland (region G in Fig. 1). Both wings are equally paralyzed and the beak has no strength, whereas mobility and control of the head still remain. In this work we demonstrate that the probability to remedy an individual in this condition by thiamine treatment is very high. The movie is taken in the field, but the specimen is placed on a black tablecloth in order to remove disturbing background and enhance contrast. Movie S1 (AVI) Other Supporting Information Files SI Appendix Balk et al. www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/0902903106 1of1 Supporting Information Wild birds of declining European species are dying from a thiamine deficiency syndrome L. Balk*, P.-Å. Hägerroth, G. Åkerman, M. Hanson, U. Tjärnlund, T. Hansson, G. T. Hallgrimsson, Y. Zebühr, D. Broman, T. Mörner, H. Sundberg *Corresponding author: [email protected] Contents Pages M & M Materials and Methods. 2–10 Text S1 Additional bird species affected by the paralytic disease. 11 Text S2 Additional results for eggs. 12–13 Text S3 Results for liver body index (LBI) in pulli. 14–15 Text S4 Breeding output and population estimates. 16–18 Text S5 Elaborated discussion of important aspects. 19–27 Acknowl. Further acknowledgements. 28 Fig. S1 a–j The 83 locations where samples were collected. 29–30 Fig. S2 a–d Pigmentation changes in the iris of the herring gull (Larus argentatus). 31 Fig. S3 Liver α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH) in common black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus).