The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

Nordmann's Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi

Final Report Nordmann’s Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi Cipto Dwi Handono1, Ragil Siti Rihadini1, Iwan Febrianto1 and Ahmad Zulfikar Abdullah1 1Yayasan Ekologi Satwa Alam Liar Indonesia (Yayasan EKSAI/EKSAI Foundation) Surabaya, Indonesia Background Many shorebirds species have declined along East Asian-Australasian Flyway which support the highest diversity of shorebirds in the world, including the globally endangered species, Nordmann’s Greenshank. Nordmann’s Greenshank listed as endangered in the IUCN Red list of Threatened Species because of its small and declining population (BirdLife International, 2016). It’s one of the world’s most threatened shorebirds, is confined to the East Asian–Australasian Flyway (Bamford et al. 2008, BirdLife International 2001, 2012). Its global population is estimated at 500–1,000, with an estimated 100 in Malaysia, 100–200 in Thailand, 100 in Myanmar, plus unknown but low numbers in NE India, Bangladesh and Sumatra (Wetlands International 2006). The population is suspected to be rapidly decreasing due to coastal wetland development throughout Asia for industry, infrastructure and aquaculture, and the degradation of its breeding habitat in Russia by grazing Reindeer Rangifer tarandus (BirdLife International 2012). Mostly Nordmann’s Greenshanks have been recorded in very small numbers throughout Southeast Asia, and there are few places where it has been reported regularly. In Myanmar, for example, it was rediscovered after a gap of almost 129 years. The total count recorded by the Asian Waterbird Census (AWC) in 2006 for Myanmar was 28 birds with 14 being the largest number at a single locality (Naing 2007). In 2011–2012, Nordmann’s Greenshank was found three times in Sumatera Utara province, N Sumatra. -

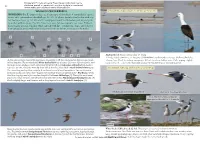

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Tasmanian Bird Report 38

Tasmanian Bird Report 38 July 2017 BirdLife Tasmania, a branch of BirdLife Australia Editor, Wynne Webber TASMANIA The Tasmanian Bird Report is published by BirdLife Tasmania, a regional branch of BirdLife Australia Number 38 © 2017 BirdLife Tasmania, GPO Box 68, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001 ISSN 0156-4935 This publication is copyright. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, except for the purposes of study or research, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of BirdLife Tasmania or the respective paper’s author(s). Acknowledgments NRM South, through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme, has provided financial assistance for the publication of this report. We thank them both for this contribution. Contents Editorial iv Wynne Webber State of Tasmania’s terrestrial birds 2014–15 1 Mike Newman, Nick Ramshaw, Sue Drake, Eric Woehler, Andrew Walter and Wynne Webber Risk of anticoagulant rodenticides to Tasmanian raptors 17 Nick Mooney Oddities of behaviour and occurrence 26 Compiler, Wynne Webber When is the best time to survey shorebirds? 31 Stephen Walsh A Eurasian Coot nests in Hobart 32 William E. Davis, Jr Changes in bird populations on Mt Wellington over a 40-year period 34 Mike Newman 2016 Summer and winter wader counts 44 (incorporating corrected tables for 2015 summer counts) Eric Woehler and Sue Drake Editorial In this Tasmanian Bird Report we institute what is hoped to be a useful and ongoing enterprise, which replaces the systematic lists of earlier years: a report on ‘The state of Tasmania’s birds’. -

Pages 345–366850.31 KB

Conservation Science W. Aust. 8 (3) : 345–366 (2013) Wader numbers and distribution on Eighty Mile Beach, north-west Australia: baseline counts for the period 1981–2003 CLIVE MINTON 1, MICHAEL CONNOR 2, DAVID PRICE 3, ROSALIND JESSOP 4, PETER COLLINS 5, HUMPHREY SITTERS 6, CHRIS HASSELL 7, GRANT PEARSON 8, DANNY ROGERS 9 1 165 Dalgetty Road Beaumaris, Victoria 3193 2 19 Pamela Grove Lower Templestowe, Victoria 3107 [email protected] 3 8 Scattor View Bridford, Exeter, Devon EX6 7JF, UK 4 Phillip Island Nature Park, PO Box 97 Cowes, Victoria 3922 5 214 Doveton Crescent Soldiers Hill, Ballarat, Victoria 3350 6 Higher Wyndcliffe Barline, Beer, Seaton, Devon EX12 3LP, UK 7 PO Box 3089 Broome, Western Australia 6725 8 Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife, PO Box 51 Wanneroo, Western Australia 6065 9 340 Ninks Road St Andrews, Victoria 3761 ABSTRACT This paper analyses ground counts and aerial surveys of high-tide wader roosts conducted over the 23-year period from 1981 to 2003, at Eighty Mile Beach, north-west Australia. It provides a baseline data set with which later count data can be compared. Over the study period, Eighty Mile Beach held a maximum of around 470,000 waders in any given year. This represented around 20% of the total number of migratory waders visiting Australia each year and around 6% of the total East Asian – Australasian Flyway migratory wader population. The most numerous species were great knot (169,000), bar-tailed godwit (110,000), greater sand plover (65,000) and oriental plover (58,000). -

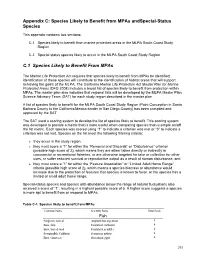

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

YELLOW THROAT the Newsletter of Birdlife Tasmania: a Branch of Birdlife Australia Number 110, Winter 2020

YELLOW THROAT The newsletter of BirdLife Tasmania: a branch of BirdLife Australia Number 110, Winter 2020 Welcome to all our new readers (supporters and new Contents members) to the Winter edition of Yellow Throat. Masked Lapwing—Is it breeding earlier this year…..2 Normally we would be letting you know when the Concern for Tasmania’s woodland birds………………...3 next BirdLife Tasmania General Meeting will be held and who will be speaking. Alas, we are still under More of the same—windfarms gaining approval through archaic assessment……………………………………..4 COVID-19 restrictions for now, and are unsure when the next meeting will take place, but it will not be be- Birdata is easy to use and helps our birdlife!...............7 fore September. Beneath the radar…………………………………………………….8 We will continue to provide updates in the e-bulletin What Happens to Out-of-Range Records in on the resumption of meetings, and also, of course, Birdata?.................................................................... .10 outings. At this stage, outings will hopefully resume in Any more oddities?....................................................11 August. In the meantime, enjoy the many interesting Bird - safe architecture…………………………………………. .12 articles we have in this issue of Yellow Throat; we South-east Tasmanian KBA report indicates climate - hope you are making the most of the birds in your related concern for some species………………………… ..14 local area. Birding in backyards initiative………………………………. ..17 In this issue of Yellow Throat, two programs are out- lined that allow the community to participate in bird Is your cat a killer?......................................................18 surveys. General Birdata surveys and Birds in Back- Cat management in Tasmania………………… .19 yards surveys are two different ways that people who Letter from the Raptor Refuge………………………………..20 love birds can record what they see. -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Post-Breeding Stopover Sites of Waders in the Estuaries of the Khairusovo, Belogolovaya and Moroshechnaya Rivers, Western Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, 2010–2012

Post-breeding stopover sites of waders in the estuaries of the Khairusovo, Belogolovaya and Moroshechnaya rivers, western Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, 2010–2012 Dmitry S. Dorofeev1 & Fedor V. Kazansky2 1 All-Russian Research Institute for Nature Protection (ARRINP), Znamenskoe-Sadki, Moscow, 117628 Russia [email protected] 2 Kronotsky State Biosphere Reserve, Ryabikova St. 48, Elizovo, Kamchatskiy Kray, 68400 Russia. [email protected] Dorofeev, D.S. & Kazansky, F.V. 2013. Post-breeding stopover sites of waders in the estuaries of the Khairusovo, Belogolovaya and Moroshechnaya rivers, western Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, 2010–2012. Wader Study Group Bull. 120(2): 119–123. Keywords: East Asian–Australasian Flyway, Kamchatka, waders, stopover site, resightings During the northern summer and autumn seasons of 2010–2012 we collected data on the numbers of waders that stop on the estuaries of the rivers Khairusovo, Belogolovaya and Moroshechnaya on the west-central coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia. Among known wader stopovers on the west coast of Kamchatka, this is the area that supports the largest numbers. We found that the most abundant species were Great Knot Calidris tenuirostris, Bar-tailed Godwit Limosa lapponica, Black-tailed Godwit L. limosa and Red-necked Stint C. ruficollis. Two globally-threatened species were also recorded: Eastern Curlew Numenius madagascarensis and Spoon-billed Sandpiper Eurynorhynchus pygmeus. At least 35 Great Knots colour-marked in NW Australia, one from South Australia and two from China were recorded in the area. We also observed several colour- marked Bar-tailed Godwits, Red-necked Stints and a Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres marked in different areas of Australia and in China. -

EPBC Act Referral Is Complete, Current and Correct

Submission #2895 - Robbins Island Renewable Energy Park, Robbins Island, Tasmania Title of Proposal - Robbins Island Renewable Energy Park, Robbins Island, Tasmania Section 1 - Summary of your proposed action Provide a summary of your proposed action, including any consultations undertaken. 1.1 Project Industry Type Energy Generation and Supply (renewable) 1.2 Provide a detailed description of the proposed action, including all proposed activities. Please see letter for detailed description of the proposed action, attached at 1.4. 1.3 What is the extent and location of your proposed action? Use the polygon tool on the map below to mark the location of your proposed action. Area Point Latitude Longitude Robbins Island 1 -40.674899476105 145.00381304524 Robbins Island 2 -40.678232305635 145.00655962727 Robbins Island 3 -40.68156496855 145.01397539038 Robbins Island 4 -40.684689176792 145.02660966353 Robbins Island 5 -40.68427259873 145.03155351957 Robbins Island 6 -40.68427259873 145.03484940962 Robbins Island 7 -40.682606387569 145.03924395764 Robbins Island 8 -40.682189796489 145.0417158647 Robbins Island 9 -40.680315231537 145.04528642972 Robbins Island 10 -40.680106929163 145.04858231978 Robbins Island 11 -40.680106929163 145.04968095678 Robbins Island 12 -40.682189796489 145.04775835774 Robbins Island 13 -40.68156496855 145.04611041271 Robbins Island 14 -40.683231205745 145.04446244673 Robbins Island 15 -40.684689176792 145.04501177571 Robbins Island 16 -40.685522261546 145.04720902876 Robbins Island 17 -40.686147084167 145.0447371217 -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------