Peeps and Related Sandpipers Peeps Are a Group of Diminutive Sandpipers That Are Notoriously Hard to Tell Apart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

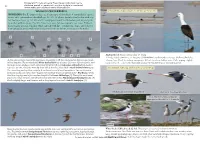

Nordmann's Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi

Final Report Nordmann’s Greenshank Population Analysis, at Pantai Cemara Jambi Cipto Dwi Handono1, Ragil Siti Rihadini1, Iwan Febrianto1 and Ahmad Zulfikar Abdullah1 1Yayasan Ekologi Satwa Alam Liar Indonesia (Yayasan EKSAI/EKSAI Foundation) Surabaya, Indonesia Background Many shorebirds species have declined along East Asian-Australasian Flyway which support the highest diversity of shorebirds in the world, including the globally endangered species, Nordmann’s Greenshank. Nordmann’s Greenshank listed as endangered in the IUCN Red list of Threatened Species because of its small and declining population (BirdLife International, 2016). It’s one of the world’s most threatened shorebirds, is confined to the East Asian–Australasian Flyway (Bamford et al. 2008, BirdLife International 2001, 2012). Its global population is estimated at 500–1,000, with an estimated 100 in Malaysia, 100–200 in Thailand, 100 in Myanmar, plus unknown but low numbers in NE India, Bangladesh and Sumatra (Wetlands International 2006). The population is suspected to be rapidly decreasing due to coastal wetland development throughout Asia for industry, infrastructure and aquaculture, and the degradation of its breeding habitat in Russia by grazing Reindeer Rangifer tarandus (BirdLife International 2012). Mostly Nordmann’s Greenshanks have been recorded in very small numbers throughout Southeast Asia, and there are few places where it has been reported regularly. In Myanmar, for example, it was rediscovered after a gap of almost 129 years. The total count recorded by the Asian Waterbird Census (AWC) in 2006 for Myanmar was 28 birds with 14 being the largest number at a single locality (Naing 2007). In 2011–2012, Nordmann’s Greenshank was found three times in Sumatera Utara province, N Sumatra. -

The Promiseuous Pectoral Sandpiper

BEHAVIOR The promiscuous Pectoral Sandpiper "nothing evolvesNorth Slope tundra more certainly than a male Pectoral Sandpiper, hooting through chilled Alaskan mist" J.P. Myers [sBARROW,ALASKA, the Pectoral a pendulous, fat-filled organ hanging deep o6-ah, o6-ah, o6-ah each syllable andpiper seasonbegins with a few prominently even while the male stands separated by a moment's silence and distant hoots sometime between the 5th immobile (Fig. 1). Its outline is en- repeatedtwo or three timesper second and 10thof June. At first hearing one has hanced by sharp contrast with the white for l0 to 15 seconds½Fig. 3 and record). difficulty accepting its source as arian. vent, and more still by the way the male Viewing this display in profile is star- The hoot is a fog horn, a sonar beam, an erects his feathers to expose their tling, but imagine what a female Pec- electronic oscillator bearing no relation darker base. toral sees. More often than not she to the sounds about it. Even after bird But the sac comes into its own when serves as the focus of his flight: the and call are linked it seems preposter- the male takes flight to hoot (Fig. 2). He male's path takes him directly over her ous. The way the call is made, the bodily flies low over the tundra, often within a in mid-hoot, perhaps only 5 cm from her distortions that male goes through to few centimeters of the upper blades of head as she feeds in the grass. He make its hoot, are visually just as odd as grass and sedge. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE SURFBIRD, APHRIZA VIRGATA JOSEPH R. JEHL, JR. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 The taxonomic relationships of the Surfbird, ( 1884) elevated the tumstone-Surfbird unit Aphriza virgata, have long been one of the to family rank. But, although they stated (p. most controversial problems in shorebird clas- 126) that Aphrizu “agrees very closely” with sification. Although the species has been as- Arenaria, the only points of similarity men- signed to a monotypic family (Shufeldt 1888; tioned were “robust feet, without trace of web Ridgway 1919), most modern workers agree between toes, the well formed hind toe, and that it should be placed with the turnstones the strong claws; the toes with a lateral margin ( Arenaria spp. ) in the subfamily Arenariinae, forming a broad flat under surface.” These even though they have reached no consensuson differences are hardly sufficient to support the affinities of this subfamily. For example, familial differentiation, or even to suggest Lowe ( 1931), Peters ( 1934), Storer ( 1960), close generic relationship. and Wetmore (1965a) include the Arenariinae Coues (1884605) was uncertain about the in the Scolopacidae (sandpipers), whereas Surfbirds’ relationships. He called it “a re- Wetmore (1951) and the American Ornithol- markable isolated form, perhaps a plover and ogists ’ Union (1957) place it in the Charadri- connecting this family with the next [Haema- idae (plovers). The reasons for these diverg- topodidae] by close relationships with Strep- ent views have never been stated. However, it silas [Armaria], but with the hind toe as well seems that those assigning the Arenariinae to developed as usual in Sandpipers, and general the Charadriidae have relied heavily on their appearance rather sandpiper-like than plover- views of tumstone relationships, because schol- like. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

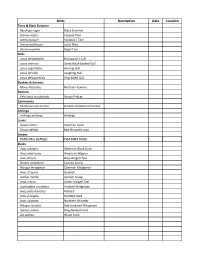

Bird Species Check List

Birds Description Date Location Terns & Black Skimmer Rynchops niger Black Skimmer Sterna caspia Caspian Tern Stema forsteri Forester's Tern Sterna antillarum Least Tern Sterna maxima Royal Tern Gulls Larus philadelphia Bonaparte's Gull Larus marinus Great Black‐backed Gull Larus argentatus Herring Gull Larus atricilla Laughing Gull Larus delawarensis Ring‐billed Gull Boobies & Gannets Morus bassanus Northern Gannet Pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus Double‐Crested Cormorant Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Anhinga Loons Gavia immer Common Loon Gavia stellata Red‐throated Loon Grebes PodilymbusPodil ymbus popodicepsdiceps PiPieded‐billbilleded GrebeGrebe Ducks Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas americana American Wigeon Anas discors Blue‐winged Teal Branta canadensis Canada Goose Mergus merganser Common Merganser Anas strepera Gadwall Aythya marila Greater Scaup Anas crecca Green‐winged Teal Lophodytes cucullatus Hooded Merganser Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Mergus serrator Red‐breasted Merganser Aythya collaris Ring‐Necked Duck Aix sponsa Wood Duck Birds Description Date Location Rails & Northern Jacana Fulica americana American Coot Rallus longirostris Clapper Rail Gallinula chloropus Common Moorhen Rallus elegans King Rail Porzana carolina Sora Long‐legged Waders Nycticorax nycticorax Black‐crowned Night‐Heron Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron Casmerodius albus Great Egret Butorides -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Ageing and Sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis Hypoleucos

ageing & sexing series Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. 10.18194/ws.00009 This series summarizing current knowledge on ageing and sexing waders is co-ordinated by Włodzimier Meissner (Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdansk, ul. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, [email protected]). See Wader Study Group Bulletin vol. 113 p. 28 for the Introduction to the series. Part 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos Włodzimierz Meissner 1, Philip K. Holland 2 & Tomasz Cofta 3 1Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdańsk, ul.Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] 232 Southlands, East Grinstead, RH19 4BZ, UK. [email protected] 3Hoene 5A/5, 80-041 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Meissner, W., P.K. Holland & T. Coa. 2015. Ageing and sexing series 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos . Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. Keywords: Common Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos , ageing, sexing, moult, plumages The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is treated as were validated using about 500 photographs available on monotypic through a breeding range that extends from the Internet and about 50 from WRG KULING ringing Ireland eastwards to Japan. Its main non-breeding area is sites in northern Poland. also vast, reaching from the Canary Islands to Australia with a few also in the British Isles, France, Spain, Portugal MOULT SCHEDULE and the Mediterranean (Cramp & Simmons 1983, del Juveniles and adults leave the breeding grounds as soon Hoyo et al. 1996, Glutz von Blotzheim et al.