Y and W Are Sometimes Vowels and Sometimes Consonants by Linda Farrell, Michael Hunter, and Tina Osenga Founding Partners, Readsters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16 Flourishing From the Start: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured? Kristin Anderson Moore, PhD, Child Trends Christina D. Bethell, PhD, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Introduction Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Every parent wants their child to flourish, and every community wants its Public Health children to thrive. It is not sufficient for children to avoid negative outcomes. Rather, from their earliest years, we should foster positive outcomes for David Murphey, PhD, children. Substantial evidence indicates that early investments to foster positive child development can reap large and lasting gains.1 But in order to Child Trends implement and sustain policies and programs that help children flourish, we need to accurately define, measure, and then monitor, “flourishing.”a Miranda Carver Martin, BA, Child Trends By comparing the available child development research literature with the data currently being collected by health researchers and other practitioners, Martha Beltz, BA, we have identified important gaps in our definition of flourishing.2 In formerly of Child Trends particular, the field lacks a set of brief, robust, and culturally sensitive measures of “thriving” constructs critical for young children.3 This is also true for measures of the promotive and protective factors that contribute to thriving. Even when measures do exist, there are serious concerns regarding their validity and utility. We instead recommend these high-priority measures of flourishing -

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim

Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim To cite this version: Dae Hwan Kim, Jin Hyung Kim. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space. Tenth International Workshop on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, Université de Rennes 1, Oct 2006, La Baule (France). inria-00105116 HAL Id: inria-00105116 https://hal.inria.fr/inria-00105116 Submitted on 10 Oct 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ligature Modeling for Recognition of Characters Written in 3D Space Dae Hwan Kim Jin Hyung Kim Artificial Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition Lab. Pattern Recognition Lab. KAIST, Daejeon, KAIST, Daejeon, South Korea South Korea [email protected] [email protected] Abstract defined shape of character while it showed high recognition performance. Moreover when a user writes In this work, we propose a 3D space handwriting multiple stroke character such as ‘4’, the user has to recognition system by combining 2D space handwriting write a new shape which is predefined in a uni-stroke models and 3D space ligature models based on that the and which he/she has never seen. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 the BASIC SOUNDS of ENGLISH 1. STOPS a Stop Consonant Is Produced with a Complete Closure of Airflow

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology THE BASIC SOUNDS OF ENGLISH 1. STOPS A stop consonant is produced with a complete closure of airflow in the vocal tract; the air pressure has built up behind the closure; the air rushes out with an explosive sound when released. The term plosive is also used for oral stops. ORAL STOPS: e.g., [b] [t] (= plosives) NASAL STOPS: e.g., [m] [n] (= nasals) There are three phases of stop articulation: i. CLOSING PHASE (approach or shutting phase) The articulators are moving from an open state to a closed state; ii. CLOSURE PHASE (= occlusion) Blockage of the airflow in the oral tract; iii. RELEASE PHASE Sudden reopening; it may be accompanied by a burst of air. ORAL STOPS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL STOPS: The blockage is made with the two lips. spot [p] voiceless baby [b] voiced 1 b. ALVEOLAR STOPS: The blade (or the tip) of the tongue makes a closure with the alveolar ridge; the sides of the tongue are along the upper teeth. lamino-alveolar stops or Check your apico-alveolar stops pronunciation! stake [t] voiceless deep [d] voiced c. VELAR STOPS: The closure is between the back of the tongue (= dorsum) and the velum. dorso-velar stops scar [k] voiceless goose [g] voiced 2. NASALS (= nasal stops) The air is stopped in the oral tract, but the velum is lowered so that the airflow can go through the nasal tract. All nasals are voiced. NASALS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL NASAL: made [m] b. ALVEOLAR NASAL: need [n] c. -

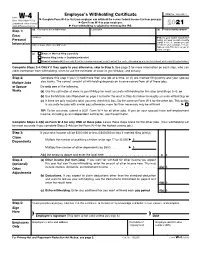

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

The Violability of Backness in Retroflex Consonants

The violability of backness in retroflex consonants Paul Boersma University of Amsterdam Silke Hamann ZAS Berlin February 11, 2005 Abstract This paper addresses remarks made by Flemming (2003) to the effect that his analysis of the interaction between retroflexion and vowel backness is superior to that of Hamann (2003b). While Hamann maintained that retroflex articulations are always back, Flemming adduces phonological as well as phonetic evidence to prove that retroflex consonants can be non-back and even front (i.e. palatalised). The present paper, however, shows that the phonetic evidence fails under closer scrutiny. A closer consideration of the phonological evidence shows, by making a principled distinction between articulatory and perceptual drives, that a reanalysis of Flemming’s data in terms of unviolated retroflex backness is not only possible but also simpler with respect to the number of language-specific stipulations. 1 Introduction This paper is a reply to Flemming’s article “The relationship between coronal place and vowel backness” in Phonology 20.3 (2003). In a footnote (p. 342), Flemming states that “a key difference from the present proposal is that Hamann (2003b) employs inviolable articulatory constraints, whereas it is a central thesis of this paper that the constraints relating coronal place to tongue-body backness are violable”. The only such constraint that is violable for Flemming but inviolable for Hamann is the constraint that requires retroflex coronals to be articulated with a back tongue body. Flemming expresses this as the violable constraint RETRO!BACK, or RETRO!BACKCLO if it only requires that the closing phase of a retroflex consonant be articulated with a back tongue body. -

Ffontiau Cymraeg

This publication is available in other languages and formats on request. Mae'r cyhoeddiad hwn ar gael mewn ieithoedd a fformatau eraill ar gais. [email protected] www.caerphilly.gov.uk/equalities How to type Accented Characters This guidance document has been produced to provide practical help when typing letters or circulars, or when designing posters or flyers so that getting accents on various letters when typing is made easier. The guide should be used alongside the Council’s Guidance on Equalities in Designing and Printing. Please note this is for PCs only and will not work on Macs. Firstly, on your keyboard make sure the Num Lock is switched on, or the codes shown in this document won’t work (this button is found above the numeric keypad on the right of your keyboard). By pressing the ALT key (to the left of the space bar), holding it down and then entering a certain sequence of numbers on the numeric keypad, it's very easy to get almost any accented character you want. For example, to get the letter “ô”, press and hold the ALT key, type in the code 0 2 4 4, then release the ALT key. The number sequences shown from page 3 onwards work in most fonts in order to get an accent over “a, e, i, o, u”, the vowels in the English alphabet. In other languages, for example in French, the letter "c" can be accented and in Spanish, "n" can be accented too. Many other languages have accents on consonants as well as vowels. -

English Phonetic Vowel Shortening and Lengthening As Perceptually Active for the Poles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Title: English phonetic vowel shortening and lengthening as perceptually active for the Poles Author: Arkadiusz Rojczyk Citation style: Rojczyk Arkadiusz. (2007). English phonetic vowel shortening and lengthening as perceptually active for the Poles. W: J. Arabski (red.), "On foreign language acquisition and effective learning" (S. 237-249). Katowice : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Phonological subsystem English phonetic vowel shortening and lengthening as perceptually active for the Poles Arkadiusz Rojczyk University of Silesia, Katowice 1. Introduction Auditory perception is one of the most thriving and active domains of psy cholinguistics. Recent years have witnessed manifold attempts to investigate and understand how humans perceive linguistic sounds and what principles govern the process. The major assumption underlying the studies on auditory perception is a simple fact that linguistic sounds are means of conveying meaning, encoded by a speaker, to a hearer. The speaker, via articulatory gestures, transmits a message encoded in acoustic waves. This is the hearer, on the other hand, who, using his perceptual apparatus, reads acoustic signals and decodes them into the meaning. Therefore, in phonetic terms, the whole communicative act can be divided into three stages. Articulatory - the speaker encodes the message by sound production. Acoustic - the message is transmitted to the hearer as acous tic waves. Auditory - the hearer perceives sounds and decodes them into the meaning. Each of the three stages is indispensable for effective communication. Of the three aforementioned stages of communication, the auditory percep tion is the least amenable to precise depiction and understanding. -

Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Diacritics: A Corpus Based Study by Claire Moore-Cantwell This is my difficulty, what marks to use and when to use them: they are so much needed, and yet so objectionable.1 ~Hopkins 1. Introduction In a letter to his friend Robert Bridges, Hopkins once wrote: “... my apparent licences are counterbalanced, and more, by my strictness. In fact all English verse, except Milton’s, almost, offends me as ‘licentious’. Remember this.”2 The typical view held by modern critics can be seen in James Wimsatt’s 2006 volume, as he begins his discussion of sprung rhythm by saying, “For Hopkins the chief advantage of sprung rhythm lies in its bringing verse rhythms closer to natural speech rhythms than traditional verse systems usually allow.”3 In a later chapter, he also states that “[Hopkins’] stress indicators mark ‘actual stress’ which is both metrical and sense stress, part of linguistic meaning broadly understood to include feeling.” In his 1989 article, Sprung Rhythm, Kiparsky asks the question “Wherein lies [sprung rhythm’s] unique strictness?” In answer to this question, he proposes a system of syllable quantity coupled with a set of metrical rules by which, he claims, all of Hopkins’ verse is metrical, but other conceivable lines are not. This paper is an outgrowth of a larger project (Hayes & Moore-Cantwell in progress) in which Kiparsky’s claims are being analyzed in greater detail. In particular, we believe that Kiparsky’s system overgenerates, allowing too many different possible scansions for each line for it to be entirely falsifiable. The goal of the project is to tighten Kiparsky’s system by taking into account the gradience that can be found in metrical well-formedness, so that while many different scansion of a line may be 1 Letter to Bridges dated 1 April 1885. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

SSC: the Science of Talking

SSC: The Science of Talking (for year 1 students of medicine) Week 3: Sounds of the World’s Languages (vowels and consonants) Michael Ashby, Senior Lecturer in Phonetics, UCL PLIN1101 Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology A Lecture 4 page 1 Vowel Description Essential reading: Ashby & Maidment, Chapter 5 4.1 Aim: To introduce the basics of vowel description and the main characteristics of the vowels of RP English. 4.2 Definition of vowel: Vowels are produced without any major obstruction of the airflow; the intra-oral pressure stays low, and vowels are therefore sonorant sounds. Vowels are normally voiced. Vowels are articulated by raising some part of the tongue body (that is the front or the back of the tongue notnot the tip or blade) towards the roof of the oral cavity (see Figure 1). 4.3 Front vowels are produced by raising the front of the tongue towards the hard palate. Back vowels are produced by raising the back of the tongue towards the soft palate. Central vowels are produced by raising the centre part of the tongue towards the junction of the hard and soft palates. 4.4 The height of a vowel refers to the degree of raising of the relevant part of the tongue. If the tongue is raised so as to be close to the roof of the oral cavity then a close or high vowel is produced. If the tongue is only slightly raised, so that there is a wide gap between its highest point and the roof of the oral cavity, then an open or lowlowlow vowel results. -

Word Study Guide for Parents

Descriptions of Word Study Patterns/Concepts Purpose of Word Study • It teaches students to examine words to discover the regularities, patterns, and conventions of the English language in order to read and spell. • It increases specific knowledge of words – the spelling and meaning of individual words. 3 Layers of word study • Alphabet – learning the relationship between letters and sounds • Pattern – learning specific groupings of letters and their sounds • Meaning – learning the meaning of groups of letters such as prefixes, suffixes, and roots. Vocabulary increases at this layer. Sorting – organizing words into groups based on similarities in their patterns or meaning. Oddballs – words that cannot be grouped into any of the identified categories of a sort. Students should be taught that there are always words that “break the rules” and do not follow the general pattern. Sound marks / / - Sound marks around a letter or pattern tell the student to focus only on the sound rather than the actual letters. (example: the word gem could be grouped into the /j/ category because it sounds like j at the beginning). Vowel (represented by V) – one of 6 letters causing the mouth to open when vocalized (a, e, i, o, u, and usually y). A single vowel sound is heard in every syllable of a word. Consonants (represented by C) – all letters other than the vowels. Consonant sounds are blocked by the lips, tongue, or teeth during articulation. Concepts in Order of Instruction Initial and final consonants – students are instructed to look at pictures and identify the beginning sound. They then connect the beginning sound to the letter that makes that sound.