INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isaak Babel," Anonymous, "He Died for Art," Nesweek (July 27, 1964)

European Writers: The Twentieth Century. Ed. George Stade. Vol. 11. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1983. Pp. 1885-1914. Babel's extant output: movie scripts, early short Isaac Babel fiction, journalistic sketches, one translation, and a few later stories that remained unpublished in Babel's lifetime (they were considered offensive either to the (1894 – 1940) party line or the censor's sense of public delicacy). His most famous work, the cycle of short stories Gregory Freidin and vignettes, Konarmiia (Red Cavalry), was first published in a separate edition in 1926. It dealt with the experiences of the Russo-Polish War of 1920 as (A version of this essay in Critical Biography was seen through the bespectacled eyes of a Russian published in European Writer of the Twentieth Jewish intellectual working, as Babel himself had Century [NY: Scribners, 1990]) done, for the newspaper of the red Cossack army. This autobiographical aura played a key rôle in the success and popularity of the cycle. The thirty three jewel-like pieces, strung together to form the first Isaac Babel (1894-1940) was, perhaps, the first edition of Red Cavalry, were composed in a short Soviet prose writer to achieve a truly stellar stature in period of time, between the summer of 1923 and the Russia, to enjoy a wide-ranging international beginning of 1925, and together constitute Babel's reputation as a grand master of the short story,1 and lengthiest work of fiction (two more pieces would be to continue to influence—directly through his own added subsequently). They also represent his most work as well as through criticism and scholarship— innovative and daring technical accomplishment. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

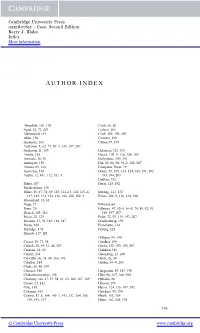

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. Blake Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Abondolo, 101, 105 Cook, 66, 80 Agud, 32, 72, 207 Corbett, 104 Aikhenvald, 191 Croft, 192, 193, 207 Allen, 150 Crowley, 100 Andersen, 163 Cutler, 99, 190 Anderson, J., 62, 71, 80–3, 135, 197, 207 Anderson, S., 109 Delancey, 123, 192 Anttila, 165 Dench, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Aristotle, 18, 30 Derbyshire, 100, 191 Armagost, 156 Dik, 62, 66, 68, 91–2, 188, 207 Artawa, 89, 124 Dionysius Thrax, 19 Austerlitz, 165 Dixon, 56, 105, 114, 124, 185, 191, 192, Austin, 12, 101, 112, 182–3 193, 194, 207 DuBois, 192 Baker, 187 Durie, 124, 192 Balakrishnan, 158 Blake, 15, 67, 78, 89, 107, 114–15, 124, 127–8, Ebeling, 121, 152 137, 143, 151, 154, 158, 186, 188, 192–3 Evans, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Bloomfield, 13, 63 Bopp, 37 Filliozat, 64 Bowe, 26 Fillmore, 47, 62–3, 66–8, 74, 80, 82, 91, Branch, 105, 116 188, 197, 207 Breen, 28, 125 Foley, 72, 92, 110, 192, 207 Bresnan, 47, 92, 185, 186, 187 Frachtenberg, 190 Bryan, 102 Franchetto, 124 Burridge, 174 Friberg, 123 Burrow, 117, 181 Gilligan, 99, 190 Caesar, 19, 73, 98 Giridhar, 100 Calboli, 18, 19, 31, 48, 207 Giv´on, 112, 192, 193, 207 Cardona, 64, 65 Goddard, 186 Carroll, 138 Greenberg, 15, 160 Carvalho, de, 31, 40, 186, 192 Groot, de, 30 Catullus, 184 Gruber, 67–9, 205 Chafe, 66, 80, 207 Chaucer, 148 Haegeman, 59, 187, 190 Chidambaranathan, 158 Hale, 96, 107, 168, 194 Chomsky, xiii, 47, 57, 58, 61, 62, 186, 187, 189 Halliday, 66 Cicero, 23, 112 Hansen, 193 Cole, 110 Harris, 124, 126, 147, 192 Coleman, 105 Hawkins, 99, 190 Comrie, 87–8, 104, 140–1, 142, 152, 154, 185, Heath, 155, 159 190, 191, 207 Heine, 162, 165, 193 219 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. -

Morphology Building Syntax: Constructive Case in Australian Languages

Morphology Building Syntax Constructive Case in Australian Languages Rachel Nordlinger Stanford University Pro ceedings of the LFG Conference University of California San Diego Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King Editors CSLI Publications httpwwwcslistanfordedupublications LFG R Nordlinger Morphology Building Syntax Constructive Case in Australia Intro duction A dening characteristic of lfg is that morphological words can carry the same kinds of functional information as syntactic phrases words and phrases are alternative means of enco ding the same syntactic relations Kaplan and Bresnan Bresnan That morphology comp etes with syntax in this way Bresnan is seen most clearly in noncongurational languages where inectional morphology takes on much of the functional load of phrase structure in more congura tional languages like English determining grammatical functions and constituency relations lfg is thus wellsuited to the analysis of noncongurationality and has pioneered muchwork on non congurational languages b oth in Australia and elsewhere Mohanan Bresnan Simpson Kro eger T Mohanan Austin and Bresnan Nordlinger and Bresnan Andrews among many others In this pap er I will b e concerned with the function of case in the dep endentmarking non congurational languages of Australia These Australian languages haveunusually extensive case marking and case concord Intuitively as has b een suggested bymany researchers working with these languages eg Hale Simpson Nash Austin Evans a it is this case marking that enables their -

The Nature of Specific Language Impairment: Optionality and Principle Conflict

The Nature of Specific Language Impairment: Optionality and Principle Conflict Lee Davies Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London August 2001 ProQuest Number: U642667 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642667 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 *I see nobody on the road,* said Alice. 7only wish I had such eyes,* the King remarked in a fretful tone. * To he able to see Nobody! And at that distance too! Why it*s as much as I can do to see real people, by this light!,... ABSTRACT This thesis focuses upon two related goals. The first is the development of an explanatory account of Specific Language Impairment (SLI) that can effectively capture the variety and complexity of the children’s grammatical deficit. The second is to embed this account within a restrictive theoretical framework. Taking as a starting point the broad characterisation of the children’s deficit, developed by Heather van der Lely in her RDDR (Representational Deficit for Dependant Relations) research program, I refine and extend her position by proposing a number of principled generalisations upon which a theoretical explanation can be based. -

Serebro Mama Lover Mp3, Flac, Wma

Serebro Mama Lover mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Mama Lover Country: Poland Released: 2011 Style: Europop MP3 version RAR size: 1746 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1158 mb WMA version RAR size: 1794 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 647 Other Formats: MIDI AAC XM VQF WAV ADX MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Mama Lover (Radio Edit) 3:29 2 Mama Lover (Original) 4:02 Mama Lover (WAWA Remix) 3 5:33 Remix – Wawa Mama Lover (WAWA Dub Mix) 4 5:31 Remix – Wawa Mama Lover (The Cube Guys Remix) 5 7:04 Remix – The Cube Guys* Mama Lover (Lockout's Remix) 6 5:00 Remix – Lockout Mama Lover (Gary Caos Remix) 7 6:57 Remix – Gary Caos Video 1 Mama Lover 4:04 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Ego Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Vae Victis Srl Phonographic Copyright (p) – Art & Music Recording Licensed From – Монолит Notes ℗ 2012 Ego/ Vae Victis Srl / Art & Music Recording Srl under exclusive license from Izdatelstvo Monolit LLC Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Mama Lover (CD, Single, 9013CDS Serebro Ego Music 9013CDS Italy 2012 Car) Mama Lover (7xFile, AAC, 5999545558327 Serebro CLS Music 5999545558327 Hungary 2012 EP, 256) Mama Lover (Remixes) Mucha Mas none Serebro none Mexico 2012 (5xFile, AAC, EP, 256) Música Mama Lover (File, AAC, 5099993462655 Serebro EMI 5099993462655 Japan 2013 Single, 256) Mama Lover (Remixes) 8033712128535 Serebro Ego Music 8033712128535 Europe 2012 (5xFile, AAC, EP, 256) Related Music albums to Mama Lover by Serebro Carol Hahn - Reach Out / Come Be My Lover Eydie Gormé - Mama, Teach Me To Dance / You Bring Out The Lover In Me Mama - Horses - The Remixes Hello Lover - Hello Lover Big Mama Thornton - Cotton Picking Blues / They Call Me Big Mama Alistair Foster - Shy Lover Billie Leigh, Lee Kelton Orchestra, Keltonaires - Mama Mama / Keep Me That Way LL Cool J - Mama Said Knock You Out - Marley Marl Remix Broadhurst - Little Lover (Remixes) Serebro - Mi Mi Mi (Remixes). -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT on most significant events of 2014 radio year and core trends in streaming broadcast and music industry' development of 2015 Part 1 – RADIO STARS & RADIO HITS ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ”, 127018 РОССИЯ, МОСКВА, СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, ДОМ 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 111, +7 (495) 645 78 55, +44 20 7193 7003, +1 (347) 274 88 41, +49 69 5780 1997, WWW.TOPHIT.RU CONTENTS Introduction.………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Radio stars and radio hits…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Artists and songs – Top Hit Music Awards 2015 winners…….…………………………………………………….……… 6 Achievements of record labels in 2014…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Top 10 of Companies with biggest number of spins on radio air……………………..……………………………….. 8 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on radio air …………………………………………………………. 9 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of spins per each song………………………………………………………. 10 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on TOP HIT 100 radio chart…………………………………. 11 Top 10 Companies with best song test results …………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Top 100 of most frequently rotated local and foreign songs on Moscow radio air 2014…………………… 13 Top 20 of hot rotation playlists, set music trends on Moscow radio air 2014.…………………………………… 15 2015: Top Hit 3.0 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 About the author……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 1 ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ” 125130 РОССИЯ МОСКВА СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 102 +7 495 645 7855 +44 20 7193 7003 +1 347 274 8841 +49 69 5780 1997 WWW.TOPHIT.RU Introduction Every day hundreds of millions of people listen to radio, driving their cars. Music, news, programs and advertising are delivered in single information flows to listeners. Today the radio air brodcast is gradually replaced by the Internet streaming, and the place of customary radiostations and TV sets is more often taken by desktops, tablet PCs and smartphones with various entertainment apps in them. -

Compound Case in Bodic Languages

Case Compounding in the Bodic Languages Michael Noonan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1. introduction Case compounding has received a certain amount of attention in the literature in recent years, in particular the phenomenon known as Suffixaufnahme [e.g. in Plank 1995a] and the various sorts of case compounding in Australian languages, some of which manifest Suffixaufnahme and other types of case compounding. There has been relatively less attention paid to the phenomenon outside of these two areas of research, and this paper is an attempt to rectify the situation somewhat by presenting data from a large family of languages, the Bodic languages, spoken in the areas straddling the spine of the Himala- yas. 1.1 bodic languages: The Bodic languages are a large and ramified branch of the Ti- beto-Burman languages.1 It is a controversial grouping in the sense that there is no con- sensus as to what should be placed within it and indeed whether it is a legitimate ge- netic grouping at all or just an assemblage of Tibeto-Burman languages that have been spoken in the region of the Himalayas long enough for the languages to have influ- enced each other in a variety of ways. A figure illustrating possible relationships among the Bodic languages can be found in Appendix 1. For our purposes, nothing crucial hinges on the assumption that these languages form a genetic grouping. It suffices that structurally these languages share certain fea- tures, among which is a tendency to compound markers of case within a phonological word. 1.2 definition of case compounding: We will define case compounding as the inclu- sion of two or more case markers within a phonological word. -

One Feature Versus Two for Kayardild Tense-Aspect-Mood

Morphology DOI 10.1007/s11525-016-9294-3 The theory of feature systems: One feature versus two for Kayardild tense-aspect-mood Erich R. Round1,2 · Greville G. Corbett2 Received: 21 October 2015 / Accepted: 5 May 2016 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Features are central to all major theories of syntax and morphology. Yet it can be a non-trivial task to determine the inventory of features and their values for a given language, and in particular to determine whether to postulate one feature or two in the same semantico-syntactic domain. We illustrate this from tense-aspect- mood (TAM) in Kayardild, and adduce principles for deciding in general between one-feature and two-feature analyses, thereby contributing to the theory of feature systems and their typology. Kayardild shows striking inflectional complexities, investigated in two major stud- ies (Evans 1995a; Round 2013), and it proves particularly revealing for our topic. Both Evans and Round claimed that clauses in Kayardild have not one but two con- current TAM features. While it is perfectly possible for a language to have two fea- tures of the same type, it is unusual. Accordingly, we establish general arguments which would justify postulating two features rather than one; we then apply these specifically to Kayardild TAM. Our finding is at variance with both Evans and Round; on all counts, the evidence which would motivate an analysis in terms of one TAM feature or two is either approximately balanced, or clearly favours an analysis with just one. -

Guida Allo Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2014 Realizzazione a Cura Dello Staff Di Eurofestival NEWS

2 JUNIOR EUROVISION SONG CONTEST: LA FESTA EUROPEA DELLA MUSICA, A MISURA DI BAMBINO Cos’è lo Junior Eurovision Song Contest? E’ la versione “junior” dell’Eurovision Song Contest, ovvero il più grande concorso musicale d’Europa ed è organizzato, come il festival degli adulti dalla EBU, European Broadcasting Union, l’ente che riunisce le tv e radio pubbliche d’Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Lo Junior Eurovision si rivolge ai bambini e ragazzi dai 10 ai 15 anni, che abbiano avuto o meno esperienze canore precedenti (regola introdotta nel 2008: prima dovevano essere esordienti assoluti). L’idea è nata nel 2003 prendendo spunto da concorsi per bambini organizzati nei paesi Scandinavi, dove l’Eurovision Song Contest (quello dei grandi) è seguito quasi come una religione. Le prime due edizioni furono infatti ospitate proprio da Danimarca e Norvegia. Curiosamente però, dopo le prime edizioni, i paesi Scandinavi si sono fatti da parte, ad eccezione della Svezia. Come funziona lo Junior Eurovision Song Contest? Esattamente come nell’Eurovision dei grandi, possiamo dunque dire che sono “le televisioni” a concorrere, ciascuna con un proprio rappresentante. Rispetto alla rassegna degli adulti, ci sono alcune sostanziali differenze: • Il cantante che viene selezionato (o il gruppo) deve essere rigorosamente della nazionalità del paese che rappresenta. L’unica eccezione è consentita per la Repubblica di San Marino, limitatamente alla possibilità di schierare cantanti italiani. Nella rassegna dei “grandi” non ci sono invece paletti in tal senso ma piena libertà. • Le canzoni devono essere eseguite obbligatoriamente in una delle lingue nazionali almeno per il 70% della propria durata, che deve essere compresa fra 2’45” e 3’ e completamente inedite al momento della presentazione ufficiale sul sito della rassegna o della partecipazione al concorso di selezione. -

Self-Quotations As Reinterpretation of the Past in the Russian Rock Band DDT

Self-quotations as reinterpretation of the past in the Russian rock band DDT Sergio Mazzanti University of Macerata [email protected] Abstract This article discusses the use of lyrical, musical and visual self-quotations in the works of DDT, one of the most important Russian rock bands. After the collapse of the USSR, the legacy of the Soviet rock movement has been the object of a nostalgic approach, both by its protagonists as individuals and by the society as a whole. Supported by different methodological approaches (Genette 1997; Yurchak 2003, 2005; Boym 2001; Chion 2016;, Veselovsky 2006), the author examines how Yury Shevchuk, DDT’s leader, uses self-quotation as an artistic tool to re-interpret the past: his own past, and at the same time the past of the country. Self-quotations can also act as a kind of dialogue between the author and society, helping us to understand the role of intertextuality in popular music, and to position it in the cultural field between the individual and the social. KEYWORDS: Russian popular music, palimpsest, nostalgia, self-quotations, appropriation, definition of popular music. Preface The collapse of the USSR in 1991 brought enormous and sudden changes in all spheres of Russian society. It is not easy to give an objective historical reconstruction of Soviet society, even if (or because) relatively little time has passed since its collapse. Especially after significant historical upheavals, people tend to reinterpret the past from the point of view of the present, often without noticing that they are doing so. Alexei Yurchak has shown how representations of the Soviet Union have quite quickly changed in the minds of the Russian people. -

Insubordination and Its ·Uses •

11 Insubordination and its ·uses NICHOLAS EVANS • 11.1 Introduction -- Prototypical finite clauses are main clauses-indeed, the ability to occur in a main clause is often taken as definitional for finiteness, e.g. by Crystal (1997: 427 }l-and prototypical nonfinite clauses are subordinate clauses. Problems thus arise when clauses that would by standard criteria be analysed as non finite are used as main clauses; examples are the use in main clauses of the English bare infinitive go (1a) or Spanish ir in (1b) (both from Etxepare and Grohmann 2005: 129), or the Italian and German infinitives used to express commands in (2). (1) a. John go to the movies?! No way, man. b. diYo ir a esa fiesta?! iJamas! l.SG go.INF to this party never 'Me go to that party? Never!' (2) a. Alza-r-si, porc-i, av-ete cap-ito? Rifa-re get.up-INF-REFL pig-PL have-2PL understand-PSTPTCP make-INF i lett-i, rna presto! Puli-r-si le scarp-e the.M.PL bed-PL but quickly clean-INF-REFL the.F.PL shoe-PL This chapter has had a long gestation, and earlier versions were presented at the Monash University Seminar Series (1989), the inaugural conference of the Association for Linguistic Typology in Vitoria Gasteiz (1995), and at the Cognitive Anthropology Research Group of the Max Planck Institut fur Psycholinguistik (1995). I thank Frans Plank for inviting me to revise it for the present volume, thereby rescuing it from further neglect, and Irina Nikolaeva for her subsequent editorial comments.