Chronic Constipation in Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peptide Therapeutics Designing a Science-Led Strategic Quality Control Program

BioProcess International Peptide SPECIAL REPORT Therapeutics Designing a Science-Led Strategic Quality Control Program INTERTEK PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES Your partner for regulatory-driven, phase appropriate analytical programs tailored to your molecule. Our experts help you to navigate the challenges of development, regulatory submission, and manufacturing. Peptide Therapeutics Designing a Science-Led Strategic Quality Control Program Shashank Sharma and Hannah Lee ince the emergence of peptide therapeutics in the 1920s with the advent of insulin therapy, the market for this product class has continued to expand with global revenues anticipatedS to surpass US$50 billion by 2024 (1). The growth of peptide therapeutics is attributed not only to improvements in manufacturing, but also to a rise in demand because of an increasingly aging population that is driving an increase in the occurrence of long-term diseases. The need for efficient and low-cost drugs and rising investments in research and development of novel drugs continues to boost market growth and fuel the emergence of generic versions that offer patients access to vital medicines at low costs. North America has been the dominant market for peptide therapeutics, with the Asia–Pacific region Insulin molecular model; the first therapeutic expected to grow at a faster rate. The global peptides use of this peptide hormone was in the market has attracted the attention of key players 1920s to treat diabetic patients. within the pharmaceutical industry, including Teva Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, amino acids to be peptides. Within that set, those Takeda, and Amgen. Those companies have made containing 10 or more are classed as polypeptides. -

Linaclotide: a Novel Therapy for Chronic Constipation and Constipation- Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Brian E

Linaclotide: A Novel Therapy for Chronic Constipation and Constipation- Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Brian E. Lacy, PhD, MD, John M. Levenick, MD, and Michael D. Crowell, PhD, FACG Dr. Lacy is Section Chief of Gastroenter- Abstract: Chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome ology and Hepatology and Dr. Levenick (IBS) are functional gastrointestinal disorders that significantly is a Gastroenterology Fellow in the affect patients’ quality of life. Chronic constipation and IBS are Division of Gastroenterology and prevalent—12% of the US population meet the diagnostic crite- Hepatology at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, New ria for IBS, and 15% meet the criteria for chronic constipation— Hampshire. Dr. Crowell is a Professor and these conditions negatively impact the healthcare system of Medicine in the Division of from an economic perspective. Despite attempts at dietary Gastroenterology and Hepatology at modification, exercise, or use of over-the-counter medications, Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. many patients have persistent symptoms. Alternative treatment options are limited. This article describes linaclotide (Linzess, Address correspondence to: Dr. Brian E. Lacy Ironwood Pharmaceuticals/Forest Pharmaceuticals), a new, first- Division of Gastroenterology and in-class medication for the treatment of chronic constipation Hepatology, Area 4C and constipation-predominant IBS. Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center 1 Medical Center Drive Lebanon, NH 03756; Tel: 603-650-5215; Fax: 603-650-5225; onstipation is -

Laxatives for the Management of Constipation in People Receiving Palliative Care (Review)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care (Review) Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, Stone P This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 5 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care (Review) Copyright © 2015 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 BACKGROUND .................................... 2 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 4 METHODS ...................................... 4 RESULTS....................................... 7 Figure1. ..................................... 8 Figure2. ..................................... 9 Figure3. ..................................... 10 DISCUSSION ..................................... 13 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 14 REFERENCES ..................................... 15 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 17 DATAANDANALYSES. 26 ADDITIONALTABLES. 26 APPENDICES ..................................... 28 WHAT’SNEW..................................... 35 HISTORY....................................... 35 CONTRIBUTIONSOFAUTHORS . 36 DECLARATIONSOFINTEREST . 36 SOURCESOFSUPPORT . 36 DIFFERENCES -

3.2.2 Misuse of Stimulant Laxatives

Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee Meeting date 10/06/2021 Agenda item 3.2.2 Title Misuse of stimulant laxatives Submitted by Medsafe Pharmacovigilance Paper type For advice Team Active ingredient Product name Sponsor Bisacodyl Bisacodyl Laxative (Pharmacy Health) PSM Healthcare Limited trading as API tablet Consumer Brands Dulcolax tablet Sanofi-Aventis New Zealand Limited Dulcolax Suppository Sanofi-Aventis New Zealand Limited *Lax-Suppositories Bisacodyl AFT Pharmaceuticals Limited *Lax-Tab tablet AFT Pharmaceuticals Limited Docusate sodium *Coloxyl tablet Pharmacy Retailing (New Zealand) Limited trading as Healthcare Logistics Docusate sodium + Coloxyl with Senna tablet Pharmacy Retailing (New Zealand) sennosides Limited trading as Healthcare Logistics *Laxsol tablet Pharmacy Retailing (New Zealand) Limited trading as Healthcare Logistics Glycerol *Glycerol Suppositories PSM Healthcare Limited trading as API Consumer Brands Sennosides *Senokot tablet Reckitt Benckiser (New Zealand) Limited Sodium picosulfate Dulcolax SP Drops oral solution Sanofi-Aventis New Zealand Limited PHARMAC funding *Pharmaceutical Schedule Lax-Tab tablets, Lax-Suppositories Bisacodyl, Coloxyl tablets and Glycerol Suppositories are fully-funded only on a prescription. Senokot tablets are part- funded. Previous MARC Misuse of stimulant laxatives has not been discussed previously. meetings International action Following a national safety review published in August 2020, the MHRA in the UK has introduced pack size restrictions, revised recommended ages for use -

1: Gastro-Intestinal System

1 1: GASTRO-INTESTINAL SYSTEM Antacids .......................................................... 1 Stimulant laxatives ...................................46 Compound alginate products .................. 3 Docuate sodium .......................................49 Simeticone ................................................... 4 Lactulose ....................................................50 Antimuscarinics .......................................... 5 Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) ..........51 Glycopyrronium .......................................13 Magnesium salts ........................................53 Hyoscine butylbromide ...........................16 Rectal products for constipation ..........55 Hyoscine hydrobromide .........................19 Products for haemorrhoids .................56 Propantheline ............................................21 Pancreatin ...................................................58 Orphenadrine ...........................................23 Prokinetics ..................................................24 Quick Clinical Guides: H2-receptor antagonists .......................27 Death rattle (noisy rattling breathing) 12 Proton pump inhibitors ........................30 Opioid-induced constipation .................42 Loperamide ................................................35 Bowel management in paraplegia Laxatives ......................................................38 and tetraplegia .....................................44 Ispaghula (Psyllium husk) ........................45 ANTACIDS Indications: -

Chronic Constipation: an Evidence-Based Review

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100272 on 7 July 2011. Downloaded from CLINICAL REVIEW Chronic Constipation: An Evidence-Based Review Lawrence Leung, MBBChir, FRACGP, FRCGP, Taylor Riutta, MD, Jyoti Kotecha, MPA, MRSC, and Walter Rosser MD, MRCGP, FCFP Background: Chronic constipation is a common condition seen in family practice among the elderly and women. There is no consensus regarding its exact definition, and it may be interpreted differently by physicians and patients. Physicians prescribe various treatments, and patients often adopt different over-the-counter remedies. Chronic constipation is either caused by slow colonic transit or pelvic floor dysfunction, and treatment differs accordingly. Methods: To update our knowledge of chronic constipation and its etiology and best-evidence treat- ment, information was synthesized from articles published in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Levels of evidence and recommendations were made according to the Strength of Recommendation taxonomy. Results: The standard advice of increasing dietary fibers, fluids, and exercise for relieving chronic constipation will only benefit patients with true deficiency. Biofeedback works best for constipation caused by pelvic floor dysfunction. Pharmacological agents increase bulk or water content in the bowel lumen or aim to stimulate bowel movements. Novel classes of compounds have emerged for treating chronic constipation, with promising clinical trial data. Finally, the link between senna abuse and colon cancer remains unsupported. Conclusions: Chronic constipation should be managed according to its etiology and guided by the best evidence-based treatment.(J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:436–451.) copyright. Keywords: Chronic Constipation, Clinical Review, Evidence-Based Medicine, Family Medicine, Gastrointestinal Problems, Systematic Review The word “constipation” has varied meanings for was established in 1991 by Drossman et al, primar- different individuals. -

Relative Efficacy of Tegaserod in a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Licensed Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation

This is a repository copy of Relative Efficacy of Tegaserod in a Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Licensed Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/149160/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Black, CJ, Burr, NE orcid.org/0000-0003-1988-2982 and Ford, AC orcid.org/0000-0001-6371-4359 (2020) Relative Efficacy of Tegaserod in a Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Licensed Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 18 (5). 1238-1239.E1. ISSN 1542-3565 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.007 © 2019 by the AGA Institute. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Black et al. Page 1 of 9 Accepted for publication 3rd July 2019 TITLE PAGE Title: Relative Efficacy of Tegaserod in a Systematic Review and Network Meta- analysis of Licensed Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation. -

Oral Lactulose Vs. Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Preparation in Colonoscopy: a Randomized Controlled Study

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14363 Oral Lactulose vs. Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Preparation in Colonoscopy: A Randomized Controlled Study Jagdeep Jagdeep 1 , Gaurish Sawant 1 , Pawan Lal 1 , Lovenish Bains 1 1. Department of Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, IND Corresponding author: Lovenish Bains, [email protected] Abstract Background Colonoscopy is the method of choice to evaluate colonic mucosa and the distal ileum, allowing the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. Appropriate bowel preparation necessitates the use of laxative medications, preferentially by oral administration. These include polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium picosulfate, and sodium phosphate (NaP). Lactulose, a semi-synthetic derivative of lactose, undergoes fermentation, acidifying the gut environment, stimulates intestinal motility, and increases osmotic pressure within the lumen of the colon. Methods In this prospective randomized controlled study, we analyzed 40 patients who presented with symptomatic bleeding per rectum and underwent bowel preparation either with lactulose or polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy. The quality of bowel preparation and other variables like palatability, discomfort, and electrolyte levels were analyzed. Results The majority of the patients (90%) were comfortable with the taste of lactulose solution, whereas the PEG group patients (55%) were equally divided on its palatability. On lactulose consumption, 40% of patients reported nausea/vomiting and around 10% of patients complained of abdominal discomfort. Serum sodium levels showed insignificant changes from 4.33 ± 0.07 mEq/L to 4.21 ± 0.18 mEq/L while potassium also remained similar from 4.26 ± 0.03 mEq/L to 4.22 ± 0.17 mEq/L. The mean Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) in patients who received lactulose solution was 6.25 ± 0.786 and in those who received PEG solution, it was 6.35 ± 0.813 (P-value = 0.59). -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

Constpation Refworks

Guidelines for Management of Idiopathic Childhood Constipation Introduction • Constipation is common in childhood affecting up to 30% of the child population. Symptoms become chronic in more than one third of patients and constipation is a common reason for referral to secondary care. • ‘Idiopathic Constipation’ refers to constipation not explained by anatomical or physiological abnormalities. • A NICE guideline entitled ‘Diagnosis and management of idiopathic childhood constipation in primary and secondary care’ was published in 2010 and the RHSC paediatric department endorses its approach. Key steps are to: 1) Identify symptoms of constipation and faecal impaction through history and physical examination 2) Recognise features in history / examination indicative of alternative underlying pathology (termed red and amber flags) 3) Provide advice on diagnosis 4) Prescribe and supervise a disimpaction regimen (where evidence of faecal impaction exists) followed by a sustained course of maintenance laxative therapy. Lothian Guideline • Click on icons for quick link to our simple to use xxx YYY iiiii flow chart formulary referral checklist. • Referrals will not be accepted without evidence of use of the above guidance. • We have provided worked examples of common scenarios encountered in primary care (Figure 4). • Finally please see our links to other useful resources (Figure 5). Click b to return to top Lothian Guideline for Management of Idiopathic Childhood Constipation. Take a history - 2 or more from the following indicate that the child is constipated: • <3 stools per week............................................................................................................................ (type 3 or 4, see Bristol Stool Form Scale) Note - this does not apply to breast fed babies over 6wks who may stool less frequently. • Large stools that block the toilet or 'rabbit dropping' type 1 stool (see Bristol Stool Form Scale) • Overflow soiling (very loose, smelly stool passed without sensation) • Poor appetite that improves with passage of large stool. -

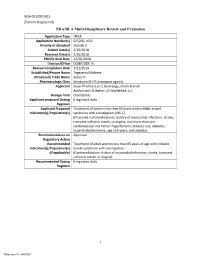

I NDA/BLA Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation

NDA 021200 S015 Zelnorm (tegaserod) NDA/BLA Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation Application Type sNDA Application Number(s) 021200, s015 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) 2/26/2018 Received Date(s) 2/26/2018 PDUFA Goal Date 12/26/2018 Division/Office DGIEP/ODE III Review Completion Date 3/22/2019 Established/Proper Name Tegaserod Maleate (Proposed) Trade Name Zelnorm Pharmacologic Class Serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist Applicant Sloan Pharma S.a.r.l, Bertrange, Cham Branch Authorized US Agent: US WorldMed, LLC Dosage form Oral tablets Applicant proposed Dosing 6 mg twice daily Regimen Applicant Proposed Treatment of women less than 65 years with irritable bowel Indication(s)/Population(s) syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). (Proposed contraindications: history of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or angina, and more than one cardiovascular risk factor: hypertension, tobacco use, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, age ≥55 years, and obesity). Recommendation on Approval Regulatory Action Recommended Treatment of adult women less than 65 years of age with irritable Indication(s)/Population(s) bowel syndrome with constipation (if applicable) (Contraindication: history of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or angina). Recommended Dosing 6 mg twice daily Regimen i Reference ID: 4407897 NDA 021200 S015 Zelnorm (tegaserod) Table of Contents Reviewers of Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation .............................................. 1 Glossary ........................................................................................................................ -

WHO Drug Information Vol

WHO Drug Information Vol. 26, No. 4, 2012 WHO Drug Information Contents International Regulatory Regulatory Action and News Harmonization New task force for antibacterial International Conference of Drug drug development 383 Regulatory Authorities 339 NIBSC: new MHRA centre 383 Quality of medicines in a globalized New Pakistan drug regulatory world: focus on active pharma- authority 384 ceutical ingredients. Pre-ICDRA EU clinical trial regulation: public meeting 352 consultation 384 Pegloticase approved for chronic tophaceous gout 385 WHO Programme on Tofacitinib: approved for rheumatoid International Drug Monitoring arthritis 385 Global challenges in medicines Rivaroxaban: extended indication safety 362 approved for blood clotting 385 Omacetaxine mepesuccinate: Safety and Efficacy Issues approved for chronic myelo- Dalfampridine: risk of seizure 371 genous leukaemia 386 Sildenafil: not for pulmonary hyper- Perampanel: approved for partial tension in children 371 onset seizures 386 Interaction: proton pump inhibitors Regorafenib: approved for colorectal and methotrexate 371 cancer 386 Fingolimod: cardiovascular Teriflunomide: approved for multiple monitoring 372 sclerosis 387 Pramipexole: risk of heart failure 372 Ocriplasmin: approved for vitreo- Lyme disease test kits: limitations 373 macular adhesion 387 Anti-androgens: hepatotoxicity 374 Florbetapir 18F: approved for Agomelatine: hepatotoxicity and neuritic plaque density imaging 387 liver failure 375 Insulin degludec: approved for Hypotonic saline in children: fatal diabetes mellitus