3.2.2 Misuse of Stimulant Laxatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Single Dose Resin-Cathartic Therapy on Serum Potassium Concentration in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease

J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1924-1930. 1998 Effect of Single Dose Resin-Cathartic Therapy on Serum Potassium Concentration in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease CHRISTINE GRUY-KAPRAL, MICHAEL EMMETT, CAROL A. SANTA ANA, JACK L. PORTER, JOHN S. FORDTRAN, and KENNETH D. FINE Departnzent of Internal Medicine, Baylor Universirs’ Medical Center, Dallas, Texas. Abstract. Hyperkalemia in patients with renal failure is fre- slightly (0.4 mEqIL) during the I 2-h experiment. This rise was quently treated with a cation exchange resin (sodium polysty- apparently abrogated by some of the regimens that included rene sulfonate, hereafter referred to as resin) in combination resin; this may have been due in part to extracellular volume with a cathartic, but the effect of such therapy on serum expansion caused by absorption of sodium released from resin. potassium concentration has not been established. This study Phenolphthalein regimens were associated with a slight rise in evaluates the effect of four single-dose resin-cathartic regimens serum potassium concentrations (similar to placebo); this may and placebo on 5 different test days in six patients with chronic have been due to extracellular volume contraction produced by renal failure. Dietary intake was controlled. Fecal potassium high volume and sodium-rich diarrhea and acidosis secondary output and serum potassium concentration were measured for to bicarbonate losses. None of the regimens reduced serum 12 h. Phenobphthalein alone caused an average fecal potassium potassium concentrations, compared with baseline levels. Be- output of 54 mEq. The addition of resin caused an increase in cause single-dose resin-cathartic therapy produces no or only insoluble potassium output but a decrease in soluble potassium trivial reductions in serum potassium concentration, and be- output; therefore, there was no significant effect of resin on cause this therapy is unpleasant and occasionally is associated total potassium output. -

Laxatives for the Management of Constipation in People Receiving Palliative Care (Review)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care (Review) Candy B, Jones L, Larkin PJ, Vickerstaff V, Tookman A, Stone P This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 5 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Laxatives for the management of constipation in people receiving palliative care (Review) Copyright © 2015 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 BACKGROUND .................................... 2 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 4 METHODS ...................................... 4 RESULTS....................................... 7 Figure1. ..................................... 8 Figure2. ..................................... 9 Figure3. ..................................... 10 DISCUSSION ..................................... 13 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 14 REFERENCES ..................................... 15 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 17 DATAANDANALYSES. 26 ADDITIONALTABLES. 26 APPENDICES ..................................... 28 WHAT’SNEW..................................... 35 HISTORY....................................... 35 CONTRIBUTIONSOFAUTHORS . 36 DECLARATIONSOFINTEREST . 36 SOURCESOFSUPPORT . 36 DIFFERENCES -

1: Gastro-Intestinal System

1 1: GASTRO-INTESTINAL SYSTEM Antacids .......................................................... 1 Stimulant laxatives ...................................46 Compound alginate products .................. 3 Docuate sodium .......................................49 Simeticone ................................................... 4 Lactulose ....................................................50 Antimuscarinics .......................................... 5 Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) ..........51 Glycopyrronium .......................................13 Magnesium salts ........................................53 Hyoscine butylbromide ...........................16 Rectal products for constipation ..........55 Hyoscine hydrobromide .........................19 Products for haemorrhoids .................56 Propantheline ............................................21 Pancreatin ...................................................58 Orphenadrine ...........................................23 Prokinetics ..................................................24 Quick Clinical Guides: H2-receptor antagonists .......................27 Death rattle (noisy rattling breathing) 12 Proton pump inhibitors ........................30 Opioid-induced constipation .................42 Loperamide ................................................35 Bowel management in paraplegia Laxatives ......................................................38 and tetraplegia .....................................44 Ispaghula (Psyllium husk) ........................45 ANTACIDS Indications: -

Assessment Report on Ricinus Communis L., Oleum Final

2 February 2016 EMA/HMPC/572973/2014 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) Assessment report on Ricinus communis L., oleum Final Based on Article 10a of Directive 2001/83/EC as amended (well-established use) Herbal substance(s) (binomial scientific name Ricinus communis L., oleum (castor oil) of the plant, including plant part) Herbal preparation Fatty oil obtained from seeds of Ricinus communis L. by cold expression Pharmaceutical forms Herbal preparation in liquid or solid dosage forms for oral use Rapporteur C. Purdel Peer-reviewer B. Kroes 30 Churchill Place ● Canary Wharf ● London E14 5EU ● United Kingdom Telephone +44 (0)20 3660 6000 Facsimile +44 (0)20 3660 5555 Send a question via our website www.ema.europa.eu/contact An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2016. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Description of the herbal substance(s), herbal preparation(s) or combinations thereof .. 4 1.2. Search and assessment methodology ..................................................................... 6 2. Data on medicinal use ........................................................................................................ 6 2.1. Information about products on the market ............................................................. -

Chronic Constipation: an Evidence-Based Review

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100272 on 7 July 2011. Downloaded from CLINICAL REVIEW Chronic Constipation: An Evidence-Based Review Lawrence Leung, MBBChir, FRACGP, FRCGP, Taylor Riutta, MD, Jyoti Kotecha, MPA, MRSC, and Walter Rosser MD, MRCGP, FCFP Background: Chronic constipation is a common condition seen in family practice among the elderly and women. There is no consensus regarding its exact definition, and it may be interpreted differently by physicians and patients. Physicians prescribe various treatments, and patients often adopt different over-the-counter remedies. Chronic constipation is either caused by slow colonic transit or pelvic floor dysfunction, and treatment differs accordingly. Methods: To update our knowledge of chronic constipation and its etiology and best-evidence treat- ment, information was synthesized from articles published in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Levels of evidence and recommendations were made according to the Strength of Recommendation taxonomy. Results: The standard advice of increasing dietary fibers, fluids, and exercise for relieving chronic constipation will only benefit patients with true deficiency. Biofeedback works best for constipation caused by pelvic floor dysfunction. Pharmacological agents increase bulk or water content in the bowel lumen or aim to stimulate bowel movements. Novel classes of compounds have emerged for treating chronic constipation, with promising clinical trial data. Finally, the link between senna abuse and colon cancer remains unsupported. Conclusions: Chronic constipation should be managed according to its etiology and guided by the best evidence-based treatment.(J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:436–451.) copyright. Keywords: Chronic Constipation, Clinical Review, Evidence-Based Medicine, Family Medicine, Gastrointestinal Problems, Systematic Review The word “constipation” has varied meanings for was established in 1991 by Drossman et al, primar- different individuals. -

Oral Lactulose Vs. Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Preparation in Colonoscopy: a Randomized Controlled Study

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14363 Oral Lactulose vs. Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Preparation in Colonoscopy: A Randomized Controlled Study Jagdeep Jagdeep 1 , Gaurish Sawant 1 , Pawan Lal 1 , Lovenish Bains 1 1. Department of Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, IND Corresponding author: Lovenish Bains, [email protected] Abstract Background Colonoscopy is the method of choice to evaluate colonic mucosa and the distal ileum, allowing the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. Appropriate bowel preparation necessitates the use of laxative medications, preferentially by oral administration. These include polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium picosulfate, and sodium phosphate (NaP). Lactulose, a semi-synthetic derivative of lactose, undergoes fermentation, acidifying the gut environment, stimulates intestinal motility, and increases osmotic pressure within the lumen of the colon. Methods In this prospective randomized controlled study, we analyzed 40 patients who presented with symptomatic bleeding per rectum and underwent bowel preparation either with lactulose or polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy. The quality of bowel preparation and other variables like palatability, discomfort, and electrolyte levels were analyzed. Results The majority of the patients (90%) were comfortable with the taste of lactulose solution, whereas the PEG group patients (55%) were equally divided on its palatability. On lactulose consumption, 40% of patients reported nausea/vomiting and around 10% of patients complained of abdominal discomfort. Serum sodium levels showed insignificant changes from 4.33 ± 0.07 mEq/L to 4.21 ± 0.18 mEq/L while potassium also remained similar from 4.26 ± 0.03 mEq/L to 4.22 ± 0.17 mEq/L. The mean Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS) in patients who received lactulose solution was 6.25 ± 0.786 and in those who received PEG solution, it was 6.35 ± 0.813 (P-value = 0.59). -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

Constpation Refworks

Guidelines for Management of Idiopathic Childhood Constipation Introduction • Constipation is common in childhood affecting up to 30% of the child population. Symptoms become chronic in more than one third of patients and constipation is a common reason for referral to secondary care. • ‘Idiopathic Constipation’ refers to constipation not explained by anatomical or physiological abnormalities. • A NICE guideline entitled ‘Diagnosis and management of idiopathic childhood constipation in primary and secondary care’ was published in 2010 and the RHSC paediatric department endorses its approach. Key steps are to: 1) Identify symptoms of constipation and faecal impaction through history and physical examination 2) Recognise features in history / examination indicative of alternative underlying pathology (termed red and amber flags) 3) Provide advice on diagnosis 4) Prescribe and supervise a disimpaction regimen (where evidence of faecal impaction exists) followed by a sustained course of maintenance laxative therapy. Lothian Guideline • Click on icons for quick link to our simple to use xxx YYY iiiii flow chart formulary referral checklist. • Referrals will not be accepted without evidence of use of the above guidance. • We have provided worked examples of common scenarios encountered in primary care (Figure 4). • Finally please see our links to other useful resources (Figure 5). Click b to return to top Lothian Guideline for Management of Idiopathic Childhood Constipation. Take a history - 2 or more from the following indicate that the child is constipated: • <3 stools per week............................................................................................................................ (type 3 or 4, see Bristol Stool Form Scale) Note - this does not apply to breast fed babies over 6wks who may stool less frequently. • Large stools that block the toilet or 'rabbit dropping' type 1 stool (see Bristol Stool Form Scale) • Overflow soiling (very loose, smelly stool passed without sensation) • Poor appetite that improves with passage of large stool. -

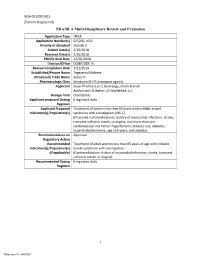

I NDA/BLA Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation

NDA 021200 S015 Zelnorm (tegaserod) NDA/BLA Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation Application Type sNDA Application Number(s) 021200, s015 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) 2/26/2018 Received Date(s) 2/26/2018 PDUFA Goal Date 12/26/2018 Division/Office DGIEP/ODE III Review Completion Date 3/22/2019 Established/Proper Name Tegaserod Maleate (Proposed) Trade Name Zelnorm Pharmacologic Class Serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist Applicant Sloan Pharma S.a.r.l, Bertrange, Cham Branch Authorized US Agent: US WorldMed, LLC Dosage form Oral tablets Applicant proposed Dosing 6 mg twice daily Regimen Applicant Proposed Treatment of women less than 65 years with irritable bowel Indication(s)/Population(s) syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). (Proposed contraindications: history of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or angina, and more than one cardiovascular risk factor: hypertension, tobacco use, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, age ≥55 years, and obesity). Recommendation on Approval Regulatory Action Recommended Treatment of adult women less than 65 years of age with irritable Indication(s)/Population(s) bowel syndrome with constipation (if applicable) (Contraindication: history of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or angina). Recommended Dosing 6 mg twice daily Regimen i Reference ID: 4407897 NDA 021200 S015 Zelnorm (tegaserod) Table of Contents Reviewers of Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation .............................................. 1 Glossary ........................................................................................................................ -

Laxatives Or Methylnaltrexone for the Management of Constipation in Palliative Care Patients (Review)

Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients (Review) Candy B, Jones L, Goodman ML, Drake R, Tookman A This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 1 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients (Review) Copyright © 2011 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 3 BACKGROUND .................................... 4 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 4 METHODS...................................... 5 RESULTS....................................... 7 Figure1. ..................................... 8 Figure2. ..................................... 9 DISCUSSION ..................................... 13 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 15 REFERENCES..................................... 15 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . .. 17 DATAANDANALYSES. 28 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Methylnaltrexone versus placebo, Outcome 1 Proportion who had rescue-free laxation within 4hours..................................... 28 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Methylnaltrexone versus placebo, Outcome 2 Laxation within 24 hours. 29 Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Methylnaltrexone versus placebo, Outcome 3 Tolerability: proportion -

Comparison of Two Cathartic Preparations, Peg-Electrolytes Solution and Sodium Phosphate Salts, As Means for Large Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy

276 ANNALS OF GASTROENTEROLOGY 2004,C. FOTIADIS, 17(3):276-279 et al Original article Comparison of two cathartic preparations, peg-electrolytes solution and sodium phosphate salts, as means for large bowel preparation for colonoscopy N. Antonakopoulos, I. Kyrlagkitsis, V. Xourgias, D.G. Karamanolis SUMMARY period of preparation, less inconvenience for the patient and better bowel cleansing. Twenty years ago, the whole The ideal bowel preparation for colonoscopy must combine procedure required a three-day low-residue diet, a the characteristics of effectiveness with the least side effects. laxative (bisacodyl) two days before the examination, a We compared the relatively novel cathartic preparation of cathartic preparation the previous day and an enema on R sodium phosphate salts (Fleet Phospho-soda ) with the the day of the examination.1 Today a single-day prepa- R widely used PEG-electrolytes solution (Klean-prep ). Fifty- ration with an oral cathartic solution is adequate. two consecutive patients referred for colonoscopy were randomised to receive either sodium phospate salts or PEG The aim of the present study was to compare the novel electrolytes. The evaluation of the two preparations was cathartic preparation of sodium phosphate salts (Fleet R based on two separate questionnaires, one completed by the Phospho-soda ), to the widely used PEG-electrolytes R endoscopist who ignored the kind of bowel preparation used solution (Klean-prep ), in terms of efficacy and tolerance and the other by the patient. Bowel preparation with sodium by the patient. phospate salts was more effective in bowel cleansing and better tolerated than PEG-electrolytes solution in terms of MATERIALS AND METHODS difficulty in intake and swallowing, fatigue, the presence of colicky abdominal pain, flatulence, vomiting and perianal We included all outpatients who underwent colono- irritation (p<0,05). -

Artigo Original / Original Article

ARQGA/1308 RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIAL COMPARING SODIUM PICOSULFATE WITH MANNITOL IN THE PREPARATION FOR COLONOSCOPY IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS Suzana MÜLLER, Carlos Fernando de Magalhães FRANCESCONI Ismael MAGUILNIK and Helenice Pankowsky BREYER ABSTRACT – Background - The cleansing of the colon for a colonoscopy exam must be complete so as to allow the visualization and inspection of the intestinal lumen. The ideal cleansing agent should be easily administered, have a low cost, and minimum collateral effects. Sodium picosulfate together with the magnesium citrate is a cathartic stimulant and mannitol is an osmotic laxative, both usually used for this purpose. Aims - Assess the colon cleanliness comparing the use of mannitol and sodium picosulfate as well as evaluate the level of patient satisfaction, the presence of foam, pain, and abdominal distension in hospitalized patients undergoing colonoscopy. Methods - A prospective, randomized, single-blind study with 80 patients that compared two groups: mannitol (40) and sodium picosulfate (40). Both groups received the same dietary orientation. The study was approved by the hospital’s Ethics and Research Committee. The endoscopist was blind to the type of preparation. Outcomes evaluated: level of the colon’s cleanliness, patient’s satisfaction, the presence of foam, abdominal pain and distension, and the duration of the exam. The data was analyzed by means of the chi-squared test for proportions and Mann-Whitney for independent samples. Results - There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in relation to the level of the colon’s cleanliness, patient’s satisfaction, the presence of foam, abdominal pain, and the duration of the exam. Fifteen percent of the exams of the mannitol group were interrupted while from the sodium picosulfate group it was 5%.