The Scottish Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CES Working Paper 07/00 RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES

CES Working Paper 07/00 RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES Author: Tim Jackson ISSN: 1464-8083 RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES Tim Jackson ISSN: 1464-8083 Published by: Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey, Guildford (Surrey) GU2 7XH, United Kingdom http://www.surrey.ac.uk/CES Publication date: 2000 © Centre for Environmental Strategy, 2007 The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and not of the Centre for Environmental Strategy. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the authors and the publishers cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials. This publication and its contents may be reproduced as long as the reference source is cited. ROYAL COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION STUDY ON ENERGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT Paper prepared as background to the Study Renewable Energy Sources March 1998 Dr Tim Jackson* and Dr Ragnar Löfstedt Centre for Environmental Strategy University of Surrey Guildford Surrey GU2 5XH E-mail: [email protected] The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the thinking of the Royal Commission. Any queries about the paper should be directed to the author indicated * above. Whilst every reasonable effort has been made to ensure accurate transposition of the written reports onto the website, the Royal Commission cannot be held responsible for any accidental errors which might have been introduced during the transcription. Table of Contents Summary 1 Introduction 2 Renewable Energy Technologies -

Who Pays? Consumer Attitudes to the Growth of Levies to Fund Environmental and Social Energy Policy Objectives Prashant Vaze and Chris Hewett About Consumer Focus

Who Pays? Consumer attitudes to the growth of levies to fund environmental and social energy policy objectives Prashant Vaze and Chris Hewett About Consumer Focus Consumer Focus is the statutory Following the recent consumer and consumer champion for England, Wales, competition reforms, the Government Scotland and (for postal consumers) has asked Consumer Focus to establish Northern Ireland. a new Regulated Industries Unit by April 2013 to represent consumers’ interests in We operate across the whole of the complex, regulated markets sectors. The economy, persuading businesses, Citizens Advice service will take on our public services and policy-makers to role in other markets from April 2013. put consumers at the heart of what they do. We tackle the issues that matter to Our Annual Plan for 2012/13 is available consumers, and give people a stronger online, consumerfocus.org.uk voice. We don’t just draw attention to problems – we work with consumers and with a range of organisations to champion creative solutions that make a difference to consumers’ lives. For regular updates from Consumer Focus, sign up to our monthly e-newsletter by emailing [email protected] or follow us on Twitter http://twitter.com/consumerfocus Consumer Focus Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 8 Background .............................................................................................................. -

A Vision for Scotland's Electricity and Gas Networks

A vision for Scotland’s electricity and gas networks DETAIL 2019 - 2030 A vision for scotland’s electricity and gas networks 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: SUPPORTING OUR ENERGY SYSTEM 03 The policy context 04 Supporting wider Scottish Government policies 07 The gas and electricity networks today 09 CHAPTER 2: DEVELOPING THE NETWORK INFRASTRUCTURE 13 Electricity 17 Gas 24 CHAPTER 3: COORDINATING THE TRANSITION 32 Regulation and governance 34 Whole system planning 36 Network funding 38 CHAPTER 4: SCOTLAND LEADING THE WAY – INNOVATION AND SKILLS 39 A vision for scotland’s electricity and gas networks 3 CHAPTER 1: SUPPORTING OUR ENERGY SYSTEM A vision for scotland’s electricity and gas networks 4 SUPPORTING OUR ENERGY SYSTEM Our Vision: By 2030… Scotland’s energy system will have changed dramatically in order to deliver Scotland’s Energy Strategy targets for renewable energy and energy productivity. We will be close to delivering the targets we have set for 2032 for energy efficiency, low carbon heat and transport. Our electricity and gas networks will be fundamental to this progress across Scotland and there will be new ways of designing, operating and regulating them to ensure that they are used efficiently. The policy context The energy transition must also be inclusive – all parts of society should be able to benefit. The Scotland’s Energy Strategy sets out a vision options we identify must make sense no matter for the energy system in Scotland until 2050 – what pathways to decarbonisation might targeting a sustainable and low carbon energy emerge as the best. Improving the efficiency of system that works for all consumers. -

Energy Policy and Biomass

National Renewable Energy Laboratory Global (International) Energy Policy and Biomass Ralph P. Overend National Renewable Energy Laboratory California Biomass Collaboration – First Annual Forum January 8th , 2004 Sacramento, CA. NREL/PR-510-35561 Operated for the U.S. Department of Energy by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle • Bechtel Understanding Policy • Policies are applied against uncertain futures! • Can be – EXPLICIT as in having an “Energy Policy” •OR – IMPLICIT derived from the sum total of previous actions • Biomass Specific Policy – At the Intersection of several policies and jurisdictions • Energy • Environment • Land Use – Agriculture – Forestry – Rural Development • Urban •ZEN Rules – not having an Explicit policy can still be an Energy Policy! – However well meaning a policy – there is a law of unintended consequences World TPES 2000 (Total Primary Energy Supply = 448 EJ) • Food TPES – 2700 Cal/person/day 6% 2% – Popn. 6.1 Billion 6% • Source for Food TPES 35% –FAO.org 10% • Nuclear conversion – kWh = 10.8 MJ • Hydro conversion 19% –kWh = 3.6 MJ • source for fuel TPES (9700 22% Mtoe) – Iea.org Oil Coal N.Gas Biomass Food Nuclear Hydro Business as Usual - World Energy according to IEA WEO2002 • 2030 time horizon • TPES grows at 1.7%/a from 9179 – 15267 Mtoe – No shortage of traditional fossil fuel resources (see next slide) – Requires considerable investment > 17 T$ (2002) • About 1% of global GDP • 50% goes for infrastructure replacement • Electricity system needs about 10 T$ (50% in T&D) • Oil and Gas each about 3 -

CLIMATE JUSTICE: the International Momentum Towards Climate Litigation

CLIMATE JUSTICE: The international momentum towards climate litigation Keely Boom, Julie-Anne Richards and Stephen Leonard CLIMATE JUSTICE: The international momentum towards climate litigation Keely Boom, Julie-Anne Richards and Stephen Leonard 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Paris Agreement is ground breaking yet contradictory. In an era of fractured multilateralism it achieved above and beyond what was considered politically possible – yet it stopped far short of what is necessary to stop dangerous climate change. In the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to pursue efforts to limit warming to 1.5C, yet the mitigation pledges on the table at Paris will result in roughly 3C of warming, with insufficient finance to implement those pledges. The Paris Agreement was widely acknowledged to signal the end of the fossil fuel era, yet it does not explicitly use the words ‘fossil fuels’ throughout the entire document, nor does it contain any binding requirements that governments commit to any concrete climate recovery steps. Now, citizens and governments are beginning to seek redress in court with ground breaking cases emerging around the world, in a whole new area of litigation, some of which can be compared with the beginnings of - and based on some of the legal precedents set by - legal action against the tobacco industry. Other new strategies are focused not only on private industry but on the sovereign responsibility of governments to preserve constitutional and public trust rights to a stable climate and healthy atmosphere on behalf of both present and future generations. Climate litigation has spread beyond the US into new jurisdictions throughout Asia, the Pacific and Europe. -

The Potential Socio-Economic Implications of Licensing the Sea 5 Area

THE POTENTIAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF LICENSING THE SEA 5 AREA A REPORT for the DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY by MACKAY CONSULTANTS June 2004 CONTENTS Section 1 : Introduction 2 : DTI scenarios 3 : The society and economy of the SEA 5 area 4 : Existing facilities and activity in the area 5 : Implications for oil and gas production and reserves 6 : Implications for capital, operating and decommissioning expenditure 7 : Implications for existing facilities 8 : Implications for employment 9 : Implications for tax revenues 10 : Social implications 11 : Conclusions Mackay Consultants Albyn House Union Street Inverness IV1 1QA Tel: 01463 223200 Fax: 01463 230869 e-mail: [email protected] The Potential Socio-Economic Implications of Licensing the SEA 5 Area A Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The UK Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) is conducting a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of licensing parts of the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) for oil and gas exploration and production. This SEA 5 is the fifth in a series planned by the DTI, which will, in stages, cover the whole of the UKCS. 1.2 The SEA 5 area is shown on the map on the following page. It is the area between the SEA 2 and SEA 4 areas. It extends from north of the Shetland Islands down the whole east coast of Scotland to the border with England. 1.3 Mackay Consultants were asked by Geotek Ltd and Hartley Anderson Ltd, on behalf of the DTI, to assess the socio-economic implications of licensing the SEA 5 area. This report sets out the results of our work, in relation to • oil and gas production, and reserves • capital, operating and decommissioning expenditure • employment • tax revenue • social impacts. -

Human Environment Baseline.Pdf

Moray Offshore Renewables Limited - Environmental Statement Telford, Stevenson and MacColl Offshore Wind Farms and Transmission Infrastructure 5 Human Environment 5.1 Commercial Fisheries 5.1 5.1.1 Introduction 5.1.1.1 This chapter summarises the baseline study of commercial fishing activities, including salmon and sea trout fisheries, in the vicinity of the three proposed development sites (Telford, Stevenson and MacColl) and the offshore transmission infrastructure (OfTI). For the purpose of this study, commercial fishing is defined as CHAPTER any legal fishing activity undertaken for declared taxable profit. 5.1.1.2 The following technical appendices support this chapter and can be found as: Technical Appendix 4.3 B (Salmon and Sea Trout Ecology Technical Report). Technical Appendix 5.1 A (Commercial Fisheries Technical Report). 5.1.1.3 For the purposes of this assessment, salmon and sea trout fisheries in the Moray Firth are separately addressed to other commercial fisheries, as a result of their being located largely in-river (with the exception of some coastal netting) and being different in nature to the majority of marine commercial fishing activities. In addition, due to the migratory behaviour of salmon and sea trout, fisheries have been assessed for all rivers flowing into the Moray Firth. It is also recognised that salmon is a qualifying feature or primary reason for Special Area of Conservation (SAC) site selection of the following rivers in the Moray Firth: Berriedale and Langwell Waters SAC (primary reason); River Moriston -

Going, Going, Gone

Going, Going, Gone The role of auctions and competition in renewable electricity support Simon Moore Edited by Guy Newey Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Danny Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), David Meller (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Richard Ehrman, Virginia Fraser, Edward Heathcoat Amory, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart Smith and Simon Wolfson. About the Authors Simon Moore joined Policy Exchange in August 2010 as a Research Fellow for the Environment & Energy Unit. Before joining Policy Exchange, Simon worked for London-based think tank The Stockholm Network. He has a Master’s degree in Public Policy from the University of Maryland and a Bachelor’s degree in Politics from Lancaster University, where he was awarded the Oakeshott Prize for best overall performance in political theory and comparative politics. Guy Newey is Head of Environment and Energy at Policy Exchange. Before joining Policy Exchange, Guy worked as a journalist, including three years as a foreign correspondent in Hong Kong. -

Annex D Major Events in the Energy Industry

Annex D Major events in the Energy Industry 2018 Energy Prices In February 2018 the Domestic Gas and Electricity (Tariff Cap) Bill was introduced to Parliament, which will put in place a requirement on the independent regulator, Ofgem, to cap energy tariffs until 2020. It will mean an absolute cap can be set on poor value tariffs, protecting the 11 million households in England, Wales and Scotland who are currently on a standard variable or other default energy tariff and who are not protected by existing price caps. An extension to Ofgem’s safeguard tariff cap was introduced in February 2018 which will see a further one million more vulnerable consumers protected from unfair energy price rises. Nuclear In June 2018 the Government announced a deal with the nuclear sector to ensure that nuclear energy continues to power the UK for years to come through major innovation, cutting-edge technology and ensuring a diverse and highly-skilled workforce. Key elements include: • a £200 million Nuclear Sector Deal to secure the UK’s diverse energy mix and drive down the costs of nuclear energy meaning cheaper energy bills for customers; • a £32 million boost from government and industry to kick-start a new advanced manufacturing programme including R&D investment to develop potential world-leading nuclear technologies like advanced modular reactors; • a commitment to increasing gender diversity with a target of 40% women working in the civil nuclear sector by 2030. 2017 Energy Policy In October 2017 the Government published The Clean Growth Strategy: Leading the way to a low carbon future, which aims to cut emissions while keeping costs down for consumers, creating good jobs and growing the economy. -

Global Gas Security Review 2018 Foreword

Global Gas Security Review Meeting Challenges in a Fast Changing Market 2018 Global Gas Security Review Meeting Challenges in a Fast Changing Market 2018 INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The IEA examines the full spectrum of energy issues including oil, gas and coal supply and demand, renewable energy technologies, electricity markets, energy efficiency, access to energy, demand side management and much more. Through its work, the IEA advocates policies that will enhance the reliability, affordability and sustainability of energy in its 30 member countries, 7 association countries and beyond. The four main areas of IEA focus are: n Energy Security: Promoting diversity, efficiency, flexibility and reliability for all fuels and energy sources; n Economic Development: Supporting free markets to foster economic growth and eliminate energy poverty; n Environmental Awareness: Analysing policy options to offset the impact of energy production and use on the environment, especially for tackling climate change and air pollution; and n Engagement Worldwide: Working closely with association and partner countries, especially major emerging economies, to find solutions to shared energy and environmental IEA member countries: concerns. Australia Austria Belgium Canada Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Secure Hungary Sustainable Ireland Together Italy Japan Korea Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic © OECD/IEA, 2018 Spain International Energy Agency Sweden Website: www.iea.org Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom United States Please note that this publication is subject to specific restrictions The European Commission that limit its use and distribution. The terms and conditions are also participates in available online at www.iea.org/t&c/ the work of the IEA. -

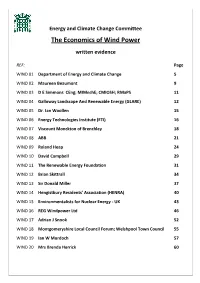

Memorandum Submitted by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (WIND 01)

Energy and Climate Change Committee The Economics of Wind Power written evidence REF: Page WIND 01 Department of Energy and Climate Change 5 WIND 02 Maureen Beaumont 9 WIND 03 D E Simmons CEng; MIMechE; CMIOSH; RMaPS 11 WIND 04 Galloway Landscape And Renewable Energy (GLARE) 12 WIND 05 Dr. Ian Woollen 15 WIND 06 Energy Technologies Institute (ETI) 16 WIND 07 Viscount Monckton of Brenchley 18 WIND 08 ABB 21 WIND 09 Roland Heap 24 WIND 10 David Campbell 29 WIND 11 The Renewable Energy Foundation 31 WIND 12 Brian Skittrall 34 WIND 13 Sir Donald Miller 37 WIND 14 Hengistbury Residents' Association (HENRA) 40 WIND 15 Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy ‐ UK 43 WIND 16 REG Windpower Ltd 46 WIND 17 Adrian J Snook 52 WIND 18 Montgomeryshire Local Council Forum; Welshpool Town Council 55 WIND 19 Ian W Murdoch 57 WIND 20 Mrs Brenda Herrick 60 WIND 21 Mr N W Woolmington 62 WIND 22 Professor Jack W Ponton FREng 63 WIND 23 Mrs Anne Rogers 65 WIND 24 Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) 67 WIND 25 Derek Partington 70 WIND 26 Professor Michael Jefferson 76 WIND 27 Robert Beith CEng FIMechE, FIMarE, FEI and Michael Knowles CEng 78 WIND 28 Barry Smith FCCA 81 WIND 29 The Wildlife Trusts (TWT) 83 WIND 30 Wyck Gerson Lohman 87 WIND 31 Brett Kibble 90 WIND 32 W P Rees BSc. CEng MIET 92 WIND 33 Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management 95 WIND 34 Councillor Ann Cowan 98 WIND 35 Ian M Thompson 99 WIND 36 E.ON UK plc 102 WIND 37 Brian D Crosby 105 WIND 38 Peter Ashcroft 106 WIND 39 Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) 109 WIND 40 Scottish Renewables 110 WIND 41 Greenpeace UK; World Wildlife Fund; Friends of the Earth 114 WIND 42 Wales and Borders Alliance 119 WIND 43 National Opposition to Windfarms 121 WIND 44 David Milborrow 124 WIND 45 SSE 126 WIND 46 Dr Howard Ferguson 129 WIND 47 Grantham Research Institute 132 WIND 48 George F Wood 135 WIND 49 Greenersky. -

Etsu/K/Bd/00187/Rep Establishing a Local

ESTABLISHING A LOCAL AUTHORITY MARKET FOR GREEN POWER ETSU/K/BD/00187/REP Contractor ESD Ltd Prepared by A Turnbull N Evans The work described in this report was carried out under contract as part of the New and Renewable Energy Programme, managed by the Energy Technology Support Unit (ETSU) on behalf of the Department of Trade and Industry. The views and judgements expressed in this report are those of the contractor and do not necessarily reflect those of ETSU or the Department of Trade and Industry First Published 1999 © Crown Copyright 1999 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The aim of this project is to establish how to maximise the potential local authority (LA) market for green power by examining the procurement and supply issues, and identifying ways to overcome the potential barriers faced both by LAs (as purchasers) and potential green electricity suppliers. To do this, it is important to understand how LAs normally procure goods and services and how power suppliers normally supply electricity. Once these two processes are understood, it is much easier to understand the issues for a LA wishing to procure green energy and for a power supplier wishing to provide green electricity, instead of buying or supplying conventional electricity. The first stage of the project was to assess the procurement processes of the LAs. This review of LA energy procurement processes resulted in a report covering the following: • background to LA structure and how this may influence procurement practices; • the liberalised market opportunities for renewable energy; • current purchasing arrangements, particularly the important role of the Standing Order; • data requirements for LAs preparing tenders; • options for, and barriers to, purchasing green energy; • conclusions, covering how the current procurement practices can be adapted to promote the procurement of green energy.