Emery–Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy–Linked Genes and Centronuclear Myopathy–Linked Genes Regulate Myonuclear Movement by Distinct Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centronuclear Myopathies Under Attack: a Plethora of Therapeutic Targets Hichem Tasfaout, Belinda Cowling, Jocelyn Laporte

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Centronuclear myopathies under attack: A plethora of therapeutic targets Hichem Tasfaout, Belinda Cowling, Jocelyn Laporte To cite this version: Hichem Tasfaout, Belinda Cowling, Jocelyn Laporte. Centronuclear myopathies under attack: A plethora of therapeutic targets. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases, IOS Press, 2018, 5, pp.387 - 406. 10.3233/JND-180309. hal-02438924 HAL Id: hal-02438924 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02438924 Submitted on 14 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 5 (2018) 387–406 387 DOI 10.3233/JND-180309 IOS Press Review Centronuclear myopathies under attack: A plethora of therapeutic targets Hichem Tasfaouta,b,c,d, Belinda S. Cowlinga,b,c,d,1 and Jocelyn Laportea,b,c,d,1,∗ aDepartment of Translational Medicine and Neurogenetics, Institut de G´en´etique et de Biologie Mol´eculaire et Cellulaire (IGBMC), Illkirch, France bInstitut National de la Sant´eetdelaRechercheM´edicale (INSERM), U1258, Illkirch, France cCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), UMR7104, Illkirch, France dUniversit´e de Strasbourg, Illkirch, France Abstract. -

Affected Female Carriers of MTM1 Mutations Display a Wide Spectrum

Acta Neuropathol DOI 10.1007/s00401-017-1748-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Afected female carriers of MTM1 mutations display a wide spectrum of clinical and pathological involvement: delineating diagnostic clues Valérie Biancalana1,2,3,4,5 · Sophie Scheidecker1 · Marguerite Miguet1 · Annie Laquerrière6 · Norma B. Romero7,8 · Tanya Stojkovic8 · Osorio Abath Neto9 · Sandra Mercier10,11,12 · Nicol Voermans13 · Laura Tanner14 · Curtis Rogers15 · Elisabeth Ollagnon‑Roman16 · Helen Roper17 · Célia Boutte18 · Shay Ben‑Shachar19 · Xavière Lornage2,3,4,5 · Nasim Vasli2,3,4,5 · Elise Schaefer20 · Pascal Laforet21 · Jean Pouget22 · Alexandre Moerman23 · Laurent Pasquier24 · Pascale Marcorelle25,26 · Armelle Magot12 · Benno Küsters27 · Nathalie Streichenberger28 · Christine Tranchant29 · Nicolas Dondaine1 · Raphael Schneider2,3,4,5,30 · Claire Gasnier1 · Nadège Calmels1 · Valérie Kremer31 · Karine Nguyen32 · Julie Perrier12 · Erik Jan Kamsteeg33 · Pierre Carlier34 · Robert‑Yves Carlier35 · Julie Thompson30 · Anne Boland36 · Jean‑François Deleuze36 · Michel Fardeau7,8 · Edmar Zanoteli9 · Bruno Eymard21 · Jocelyn Laporte2,3,4,5 Received: 9 May 2017 / Revised: 24 June 2017 / Accepted: 2 July 2017 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany 2017 Abstract X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM), a females and to delineate diagnostic clues, we character- severe congenital myopathy, is caused by mutations in the ized 17 new unrelated afected females and performed a MTM1 gene located on the X chromosome. A majority of detailed comparison with previously reported cases at the afected males die in the early postnatal period, whereas clinical, muscle imaging, histological, ultrastructural and female carriers are believed to be usually asymptomatic. molecular levels. Taken together, the analysis of this large Nevertheless, several afected females have been reported. cohort of 43 cases highlights a wide spectrum of clini- To assess the phenotypic and pathological spectra of carrier cal severity ranging from severe neonatal and generalized weakness, similar to XLMTM male, to milder adult forms. -

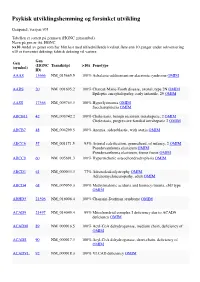

Psykisk Utviklingshemming Og Forsinket Utvikling

Psykisk utviklingshemming og forsinket utvikling Genpanel, versjon v03 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC >x10 Andel av genet som har blitt lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering x10 er forventet dekning; faktisk dekning vil variere. Gen Gen (HGNC Transkript >10x Fenotype (symbol) ID) AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 100% Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29 OMIM AASS 17366 NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCB11 42 NM_003742.2 100% Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 OMIM Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 OMIM ABCB7 48 NM_004299.5 100% Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia OMIM ABCC6 57 NM_001171.5 93% Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste OMIM ABCC9 60 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 77% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABCD4 68 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 21396 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 21497 NM_014049.4 99% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM 89 NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS 90 NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL 92 NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE Et Al

US 20160281 166A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 29, 2016 (54) METHODS AND SYSTEMIS FOR SCREENING Publication Classification DISEASES IN SUBJECTS (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: PARABASE GENOMICS, INC., CI2O I/68 (2006.01) Boston, MA (US) C40B 30/02 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Arindam BHATTACHARJEE, G06F 9/22 (2006.01) Andover, MA (US); Tanya (52) U.S. Cl. SOKOLSKY, Cambridge, MA (US); CPC ............. CI2O 1/6883 (2013.01); G06F 19/22 Edwin NAYLOR, Mt. Pleasant, SC (2013.01); C40B 30/02 (2013.01); C12O (US); Richard B. PARAD, Newton, 2600/156 (2013.01); C12O 2600/158 MA (US); Evan MAUCELI, (2013.01) Roslindale, MA (US) (21) Appl. No.: 15/078,579 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Mar. 23, 2016 Related U.S. Application Data The present disclosure provides systems, devices, and meth (60) Provisional application No. 62/136,836, filed on Mar. ods for a fast-turnaround, minimally invasive, and/or cost 23, 2015, provisional application No. 62/137,745, effective assay for Screening diseases, such as genetic dis filed on Mar. 24, 2015. orders and/or pathogens, in Subjects. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 1 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS S{}}\\93? sau36 Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 2 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 &**** ? ???zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz??º & %&&zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz &Sssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss & s s sS ------------------------------ Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 3 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 23 25 20 FG, 2. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 4 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 : S Patent Application Publication Sep. -

Myopathies Infosheet

The University of Chicago Genetic Services Laboratories 5841 S. Maryland Ave., Rm. G701, MC 0077, Chicago, Illinois 60637 Toll Free: (888) UC GENES (888) 824 3637 Local: (773) 834 0555 FAX: (773) 702 9130 [email protected] dnatesting.uchicago.edu CLIA #: 14D0917593 CAP #: 18827-49 Gene tic Testing for Congenital Myopathies/Muscular Dystrophies Congenital Myopathies Congenital myopathies are typically characterized by the presence of specific structural and histochemical features on muscle biopsy and clinical presentation can include congenital hypotonia, muscle weakness, delayed motor milestones, feeding difficulties, and facial muscle involvement (1). Serum creatine kinase may be normal or elevated. Heterogeneity in presenting symptoms can occur even amongst affected members of the same family. Congenital myopathies can be divided into three main clinicopathological defined categories: nemaline myopathy, core myopathy and centronuclear myopathy (2). Nemaline Myopathy Nemaline Myopathy is characterized by weakness, hypotonia and depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes. Weakness is typically proximal, diffuse or selective, with or without facial weakness and the diagnostic hallmark is the presence of distinct rod-like inclusions in the sarcoplasm of skeletal muscle fibers (3). Core Myopathy Core Myopathy is characterized by areas lacking histochemical oxidative and glycolytic enzymatic activity on histopathological exam (2). Symptoms include proximal muscle weakness with onset either congenitally or in early childhood. Bulbar and facial weakness may also be present. Patients with core myopathy are typically subclassified as either having central core disease or multiminicore disease. Centronuclear Myopathy Centronuclear Myopathy (CNM) is a rare muscle disease associated with non-progressive or slowly progressive muscle weakness that can develop from infancy to adulthood (4, 5). -

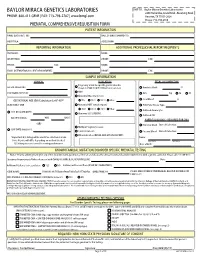

Prenatal Testing Requisition Form

BAYLOR MIRACA GENETICS LABORATORIES SHIP TO: Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories 2450 Holcombe, Grand Blvd. -Receiving Dock PHONE: 800-411-GENE | FAX: 713-798-2787 | www.bmgl.com Houston, TX 77021-2024 Phone: 713-798-6555 PRENATAL COMPREHENSIVE REQUISITION FORM PATIENT INFORMATION NAME (LAST,FIRST, MI): DATE OF BIRTH (MM/DD/YY): HOSPITAL#: ACCESSION#: REPORTING INFORMATION ADDITIONAL PROFESSIONAL REPORT RECIPIENTS PHYSICIAN: NAME: INSTITUTION: PHONE: FAX: PHONE: FAX: NAME: EMAIL (INTERNATIONAL CLIENT REQUIREMENT): PHONE: FAX: SAMPLE INFORMATION CLINICAL INDICATION FETAL SPECIMEN TYPE Pregnancy at risk for specific genetic disorder DATE OF COLLECTION: (Complete FAMILIAL MUTATION information below) Amniotic Fluid: cc AMA PERFORMING PHYSICIAN: CVS: mg TA TC Abnormal Maternal Screen: Fetal Blood: cc GESTATIONAL AGE (GA) Calculation for AF-AFP* NTD TRI 21 TRI 18 Other: SELECT ONLY ONE: Abnormal NIPT (attach report): POC/Fetal Tissue, Type: TRI 21 TRI 13 TRI 18 Other: Cultured Amniocytes U/S DATE (MM/DD/YY): Abnormal U/S (SPECIFY): Cultured CVS GA ON U/S DATE: WKS DAYS PARENTAL BLOODS - REQUIRED FOR CMA -OR- Maternal Blood Date of Collection: Multiple Pregnancy Losses LMP DATE (MM/DD/YY): Parental Concern Paternal Blood Date of Collection: Other Indication (DETAIL AND ATTACH REPORT): *Important: U/S dating will be used if no selection is made. Name: Note: Results will differ depending on method checked. Last Name First Name U/S dating increases overall screening performance. Date of Birth: KNOWN FAMILIAL MUTATION/DISORDER SPECIFIC PRENATAL TESTING Notice: Prior to ordering testing for any of the disorders listed, you must call the lab and discuss the clinical history and sample requirements with a genetic counselor. -

Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Precision Panel Overview Indications Clinical

Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Precision Panel Overview Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (RPL) is one of the most common obstetric complications, affecting more than 30% of conceptions. These can occur during preimplantation, pre-embryonic, embryonic, early fetal, late fetal and stillbirth. An important number of losses are due to genetic abnormalities, nonetheless 50% of early pregnancy losses have been associated with chromosomal abnormalities. The majority are due to de novo non-disjunctional events during meiosis and balanced paternal translocations. Traditionally, the assessment of recurrent pregnancy loss was based on karyotyping techniques. However, advances in molecular genetic technology have provided an array of information regarding genetic causes and risk factors for pregnancy loss. One of the most innovative techniques with a significant role in RPL is preimplantation genetic testing in in vitro fertilization cycles. The Igenomix Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Precision Panel can be used to make a directed and accurate differential diagnosis of inability to carry out a full pregnancy ultimately leading to a better management and achieve a healthy baby at home. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the genes involved in this disease using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully understand the spectrum of relevant genes involved. Indications The Igenomix Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Precision Panel is indicated for those patients the following manifestations: - Inability to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse - Family history of infertility - Personal history of recurrent miscarriages - Family history of recurrent miscarriages - Previous failed IVF cycles - Other failed assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatments Clinical Utility The clinical utility of this panel is: - The genetic and molecular confirmation for an accurate clinical diagnosis of a symptomatic patient. -

Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Muscular Dystrophy / Myopathy Panel

Comprehensive Muscular Dystrophy / Myopathy Panel Test code: NE0701 Is a 125 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. In addition, it also includes the maternally inherited mitochondrial genome. Is ideal for patients with distal myopathy or a clinical suspicion of muscular dystrophy. Includes the smaller Nemaline Myopathy Panel, LGMD and Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Panel, Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy Panel and Collagen Type VI-Related Disorders Panel. About Comprehensive Muscular Dystrophy / Myopathy Muscular dystrophies and myopathies are a complex group of neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders that typically result in progressive muscle weakness. The age of onset, affected muscle groups and additional symptoms depend on the type of the disease. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) is a group of disorders with atrophy and weakness of proximal limb girdle muscles, typically sparing the heart and bulbar muscles. However, cardiac and respiratory impairment may be observed in certain forms of LGMD. In congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD), the onset of muscle weakness typically presents in the newborn period or early infancy. Clinical severity, age of onset, and disease progression are highly variable among the different forms of LGMD/CMD. Phenotypes overlap both within CMD subtypes and among the congenital muscular dystrophies, congenital myopathies, and LGMDs. Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) is a condition that affects mainly skeletal muscle and heart. Usually it presents in early childhood with contractures, which restrict the movement of certain joints – most often elbows, ankles, and neck. Most patients also experience slowly progressive muscle weakness and wasting, beginning with the upper arm and lower leg muscles and progressing to shoulders and hips. -

Psykisk Utviklingshemming

Psykisk utviklingshemming Genpanel, versjon v01 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC Kolonnen >x10 viser andel av genet som vi forventer blir lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering Gen Transkript >10x Fenotype AAAS NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AASS NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCC9 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 NM_000033.3 76% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM ABCD4 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 NM_014049.4 100% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD deficiency OMIM ACAT1 NM_000019.3 100% Alpha-methylacetoacetic aciduria OMIM ACO2 NM_001098.2 97% Infantile cerebellar-retinal degeneration OMIM ACOX1 NM_004035.6 100% Peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase deficiency OMIM ACSL4 NM_004458.2 99% Mental retardation, X-linked 63 OMIM ACTA2 NM_001613.2 100% Moyamoya disease 5 OMIM Multisystemic smooth muscle dysfunction syndrome OMIM Gen Transkript >10x Fenotype ACTB NM_001101.3 100% ?Dystonia, juvenile-onset OMIM Baraitser-Winter syndrome 1 OMIM ACTG1 NM_001614.3 100% Baraitser-Winter syndrome 2 OMIM Deafness, autosomal dominant 20/26 OMIM ACVR1 NM_001105.4 100% Fibrodysplasia ossificans -

Expert Reviewers for Orphanet in 2020 2

2020 Expert reviewers for Orphanet in 2020 www.orpha.net www.orphadata.org o METHODOLOGY Differential diagnosis This document provides the list of Orphanet expert o Genetic counseling (if relevant) reviewers having contributed to the update and o Antenatal diagnosis (if relevant) quality control of scientific information contained o Management and treatment in the Orphanet database of Rare Diseases in 2020. o Prognosis - Disability facts related to rare diseases. Experts were identified through their publications, and their activity related to the given In some cases, the experts are contacted to answer disease/group of diseases (research projects, a specific question (nomenclature, genetics, clinical trials, expert centres and dedicated classifications, or epidemiological data) in order to networks): more information on the expert update the Orphanet content, or to carry out selection procedure will be available soon on quality control of the data. Please note that the www.orpha.net. Once identified, experts receive experts contacted to answer this type of question an invitation to examine, validate, correct or are not cited on the disease page on the Orphanet complete scientific information related to a given website: the expert cited on the disease page is the disease and produced based on peer-reviewed one having contributed to the text concerning the publications.Experts are solicited for their input on disease. one, or a number, of the following: - Nomenclature: preferred term and synonyms Data presentation - Related genes and the type of relationship Experts are listed by alphabetical order of their between the gene and the diseases, name and with the expertised disease name and namely: genes are annotated as causative, ORPHA code of the disease/ group of diseases, and modifiers (both from germline or somatic their affiliation to a European Reference Network mutations), major susceptibility factors or (ERN) if they have contributed on behalf of an ERN. -

Myotubular/Centronuclear Myopathy and Central Core Disease

Review Article Myotubular/centronuclear myopathy and central core disease Chieko Fujimura-Kiyono, Gabor Z. Racz, Ichizo Nishino Department of Neuromuscular Research, National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, 4-1-1 Ogawahigashi-Cho Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8502, Japan The term congenital myopathy is applied to muscle disorders Despite their genetic heterogeneity, the clinical presenting with generalized muscle weakness and hypotonia features have some characteristics in common. Main from early infancy with delayed developmental milestones. symptoms are generalized muscle weakness and The congenital myopathies have been classiÞ ed into various hypotonia, typically presenting at birth or in infancy. The categories based on morphological Þ ndings on muscle biopsy. clinical severity is highly variable from a mild, almost Although the clinical symptoms may seem homogenous, the asymptomatic form, to a severe form characterized by genetic basis is remarkably variable. This review will focus marked hypotonia at birth. Muscle weakness can be on myotubular myopathy, centronuclear myopathy, central very subtle in childhood and thus can only present core disease, and congenital neuromuscular disease with during adult years. Dysmorphic facies is very common uniform Type 1 Þ ber, myopathies that are subjects of our due to facial muscle involvement, and when this does ongoing examinations. occur, the onset is thought to be in utero. High arched palate is often documented in almost all patients with Key words: Central core disease, centronuclear myopathy, this disease. Scoliosis and contracture of joints are congenital myopathy, congenital neuromuscular disease with seen early in childhood, especially in infantile or child uniform Type 1 Þ bers, myotubular myopathy onset form. -

Prenatal Comprehensive Requisition

BAYLOR GENETICS PHONE CONNECT 2450 HOLCOMBE BLVD. 1.800.411.4363 GRAND BLVD. RECEIVING DOCK FAX HOUSTON, TX 77021-2024 1.800.434.9850 PRENATAL COMPREHENSIVE REQUISITION PATIENT INFORMATION (COMPLETE ONE FORM FOR EACH PERSON TESTED) / / Fetus of: Patient Last Name Patient First Name MI Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / Biological /Sex Fetus of: Patient Last Name Patient First Name MI Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) Address City State Zip Phone Patient discharged from Biological Sex: the hospital/facility: Female Male Unknown Accession # Hospital / Medical Record # Yes No Gender identity (if diff erent from above): REPORTING RECIPIENTS Ordering Physician Institution Name Email (Required for International Clients) Phone Fax ADDITIONAL RECIPIENTS Name Email Fax Name Email Fax PAYMENT (FILL OUT ONE OF THE OPTIONS BELOW) SELF PAYMENT Pay With Sample Bill To Patient INSTITUTIONAL BILLING Institution Name Institution Code Institution Contact Name Institution Phone Institution Contact Email INSURANCE REQUIRED ITEMS 1. Copy of the Front/Back of Insurance Card(s) 2. ICD10 Diagnosis Code(s) 3. Name of Ordering Physician 4. Insured Signature of Authorization / / / / Name of Insured Insured Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) Name of Insured Insured Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) Patient's Relationship to Insured Phone of Insured Patient's Relationship to Insured Phone of Insured Address of Insured Address of Insured City State Zip City State Zip Primary Insurance Co. Name Primary Insurance Co. Phone Secondary Insurance Co. Name Secondary Insurance Co. Phone Primary Member Policy # Primary Member Group # Secondary Member Policy # Secondary Member Group # By signing below, I hereby authorize Baylor Genetics to provide my insurance carrier any information necessary, including test results, for processing my insurance claim.