Classical Sāṁkhya on the Authorship of the Vedas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda MITHUN HOWLADAR Ph. D Scholar, Department of Sanskrit, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal Received: May 22, 2018 Accepted: July 11, 2018 ABSTRACT We can generally say, any composition which has a musical sound, is called chanda. Chanda has been one of the Vedāṅgas since Vedic period. Vedic verses are composed in several chandas. The number of Vedic chandas is 21, out of which 7 are mainly used. Earliest poetic composition in public language (laukika Sanskrit) started from Valmiki, later it became a fashion and then a discipline for composition (kāvya). But here has been a difference in Vedic and laukika chandas. Where Vedic chnadas are identified by the number of syllables (varṇa or akṣara) in a line of verse or whole verse and the number of lines in the verse, laukika chanda is identified by the order of the laghu-guru syllables. The number of the laukika chandas is not yet finally defined but many texts have been composed describing the different number of chandas. Each chanda of laukika Sanskrit (post Vedic Sanskrit) consists of four pādas or caraṇas, that is, the fourth part of the chanda. Keywords: Chanda, Vedāṅgas, Chandaśāstra, pāda, Chandomañjarī. Introduction: Veda, the oldest literature in the world, is also called Chandas because the Vedic mantras (compositions) are all metric compositions (Chandobaddha). All the four Saṁhitās (with some exceptions in Yajurveda and Atharvaveda) are of this nature. -

Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India

Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research ISSN NO: 0022-1945 Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India Ceazer Gonsalves Assistant Professor Department of English Milagres College, Udupi, Karnataka Email: [email protected] Abstract Language is a medium through which we express our thought. While the literature is a mirror which reflects ideas and philosophies which govern our society, hence to know any particular culture and its traditions it is very important we understand the evolution of its language and the various forms of literature like poetry, plan drama, religious and non religious writing. Indian language play a very important role in our culture and one of the earliest language is Sanskrit ever since human being have invented scripts, writing has reflected the culture, life style, society and the polity of the contemporary society. Each culture evolved its own language and creates a number of literary bases and this literary base of civilization tells us about the evolution of its language and culture through the span of centuries. As we know Sanskrit language is a mother of most of the Indian language .The Vedas and Puranas, Mahabharata, Ramayana all these works were written in Sanskrit language and also variety of secular and regional literature created in the past so that we can understand better. It is among the 22 language listed in the Indian Constitution .Sanskrit gave importance to study linguist scientifically during 18th and 19th century. Sanskrit is the only language that transcended the barriers of regions and boundaries from the north to the south and east to the west .There is no part of India that has not contributed to all being affected by language. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

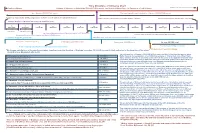

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

![History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7681/history-of-indian-philosophy-upani%C3%B1ads-key-terms-questions-pin-d%C5%93-%C3%A4%C3%BCn-aatmn-xmr-s-sar-kmr-mae-aannd-847681.webp)

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions KEY TERMS %pin;dœ *to sit down near to, to approach *the sitting down at the feet of another to listen to his words, hence, secret knowledge upaniñad *the mystery which underlies or rests underneath the external system of things Upanishad *esoteric doctrine, secret doctrine, words of mystery *a class of philosophical writings *lit. growth, expansion, evolution, swelling of the spirit or soul äün! *the sacred word, the Veda, a sacred text or Mantra (in Vedas) *the sacred syllable OM brahman *religious or spiritual knowledge brahman *the One, self-existent impersonal Spirit, universal Soul, Divine Essence and source from which all created things emanate or with which they are identified and to which they return, the Absolute, the Eternal AaTmn! *variously derived from: to breathe, to move, to blow, the breath ätman *the soul, principle of life and sensation atman *the highest personal principle of life xmR *that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, law dharma *right, justice dharma *virtue, morality, religion, religious merit, good works s<sar *going or wandering through, undergoing trasmigration *a course, passage, passing through a succession of states, circuit of mundane saàsära existence, the world, secular life, worldly illusion samsara kmR from kri, to act; thus action, performance *making, doing, performing karma (the law governing the fruit of action) karma mae] *emancipation, liberation, release mokña *release from worldly existence or transmigration, final -

Chanting Sanskrit Verses in Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Chanting Sanskrit verses in Gaudiya Vaishnavism – Jagadananda Das – Mangalacharan om ajJAna-timirAndhasya jJAnAJjanA-zalAkayA cakSur unmIlitaM yena tasmai zrI-gurave namaH nAma-zreSThaM manum api zacI-putram atra svarUpaM rUpaM tasyAgrajam uru-purim mAthurIM goSTha-vATIm rAdhA-kuNDaM giri-varam aho rAdhikA-mAdhavAzAM prApto yasya prathita-kRpayA zrI-guruM taM nato ‘smi I bow my head again and again to the holy preceptor, through whose most celebrated mercy I have received the best of all names, the initiation mantra, Sri Sachinandan Mahaprabhu, Svarupa, Rupa and his older brother Sanatan, the extensive dominions of Mathurapuri, a dwelling place in the pasturing grounds [of Krishna], Radha Kund, the chief of all mountains, Sri Govardhan, and most pointedly of all, the hope of attaining the lotus feet of Sri Radha Madhava. Introduction One of the things that attracts many people to Indian religion and to Vaishnavism in particular is the beauty of the Sanskrit language. One of the most attractive features of Sanskrit is its verse. The complex Sanskrit metres have a majestic sonority that is unmatched in any other language. A Sanskrit verse properly chanted seems to carry an authority that confirms and supports its meaning. In this little article I am going to discuss some features of Sanskrit prosody so that students and devotees can learn how to pronounce and chant Sanskrit verses in the proper manner. We will start by reviewing Sanskrit pronunciation. Then we will discuss some of the rules of prosody. The word “prosody” means the study of metrical composition, that is to say, the rules for creating verse. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha and Surya Siddhantha ?

- In search of UNKNOWN How ancient are Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha and Surya Siddhantha ? वेदमयीं नादमयीं बिꅍदुमयीं परपदोद्यददꅍदुमयीं मꅍरमयीं तꅍरमयीं प्रकृबतमयीं नौबम बवश्वबवक्रुबतमयीं Pidaparty Purna Satya Hariprasad e-mail: [email protected] Dated 27th December 2017 1 Abstract Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha, Surya Siddhanta are known as “apaurusheyas” meaning that their author and their period is unknown. No serious attempt seems to have been made to determine the age of these ‘apaurusheyas’. In this short paper, an attempt has been made by the author to determine VEDIC AGE using Equinoxes and their precession. He relied heavily on available evidence in Rig-Veda, Vedanga Jyotisha, Brahma Siddhanta, Surya Siddhanta etc and quoted extensively from these sources to support his contentions. The author is neither a scholar nor a scientist. At best he may be called an ANALYST with bare minimum knowledge of Sanskrit. He has abundant curiosity to search for the truth beyond what is known. 2 In search of UNKNOWNs In Hindu mythology, Brahma is known to be responsible for creation of the Universe – including Earth, Planets, stars, oceans, living and non-living beings, सवेषामेव जंतूनां शतमेव आयु셁च्यते तद्चच्वासप्राण काल: समस्त्वेष बवबनणणयः Brahma’s life-span is also limited to 100 years in his time scale. Time Scales of Brahma and Humans are very different. Brahma Siddhanta or Paitamaha Siddhanta provides details of time scale in Brahma’s life and their equivalents solar years in time scale of human beings. In brief some significant details together with results of analysis are given below: Serial No Brahma’s Time scale Time scale for humans 1.1 Ahoratra (day & night) 8640 million years 1.2 Maasa (month) 259,200 million years 1.3 Varsha (a year) 3,110,400 million solar years 1.4 Life-span of Brahma – 100 years 311,040,000 million solar years 2.1 No. -

Hindu Scriptures

Hindu Scriptures Hinduism consists of an extensive collection of ancient religious writings and oral accounts that expound upon eternal truths, some of which Hindus believe to have been divinely revealed and realized by their ancient sages and enlightened individuals. Hindu scriptures (such as the Vedas, Upanishads, Agamas, and Puranas), epics (the Bhagavad Gita and Ramayana), lawbooks, and other philosophical and denominational texts, have been passed on for generations through an oral and written tradition. Since spiritual seekers have different levels of understanding, scriptural teachings are presented in a variety of ways to provide guidance to all seekers. Scripture in Hinduism, however, does not have the same place as it does in many other religious traditions. W hile the Vedas and other sacred writings are considered valid sources for knowledge about God, other means of knowledge, such as personal experience of the Divine, are regarded highly as well. Some Hindu philosophers have taught that these other means of knowledge should be seen as secondary to scripture. But other Hindu philosophers have taught that religious experience can be considered equal or even superior to scriptural teachings. Hindu scriptures are classified broadly into two categories: Shruti and Smriti. The word Shruti literally means “heard”, and consists of what Hindus believe to be eternal truths akin to natural law. Hindus believe these truths are contained in the vibrations of the universe. It was the ancient sages, Hindus say, who realized these eternal truths through their meditation, and then transmitted them orally. The term Shruti is generally applied to the Vedas and includes the Upanishads, which constitute the fourth and final part of the Vedas. These texts are revered as “revealed” or divine in origin and are believed to contain the foundational truths of Hinduism. -

Vedic Mathematics and the Spiritual Dimension

The Secret of High-speed mental computations Vedic Vision “There are things which seem incredible to most men who have not studied mathematics.” – Archimedes. “Spiritually advanced cultures were not ignorant of the principles of mathematics, but they saw no necessity to explore those principles beyond that which was helpful in the advancement of God realization.” – Vedic Mathematics and the Spiritual Dimension. 4 frailties We have imperfect senses. Karana-patava We fall into illusion. pramada We make mistakes. bhrama We have cheating propensities. vipralipsa Descending Vedic knowledge Perfect [CC Adi 2.86, CC Adi 7.107] VEDIC KNOWLEDGE Revealed Absolute Truth Composed by sages Every word unchanged eternally SRUTI SMRTI Wording may change from age to age VEDAS UPAVEDAS Ritual Sutras Tantras Rg, Yajur, Dhanurveda VEDANGAS Connected to Spoken by Lord Pancaratras Puranas Itihasas Six Darshanas Sama, Atharva Ayurveda, Kalpa-vedanga Siva to Parvati Gandharvaveda, Sthapatyaveda Smarta Sutras Srauta Sutras Samhitas Kalpa Vaisnava explains 18 Major mantras ritual details worship public yajnas Srauta Brahmanas Sutras Grhya Sutras Siksa ritual explanation explains pronunciation 18 Minor of mantras home yajnas Tamasic Aranyakas Vyakarana Sulba Dharma Sutras esoteric explanation grammar Sutras Law books of mantras Rajasic Upanisads Nirukta Jnana-kanda etymology Dharma Sastras philosophy of Brahman including Manu- Sattvic samhita and others Chandas meters Jyotisa Vedanta Mimamsa Nyaya Vaisesika (Gautama) astronomy-time (Vyasa) (Jaimini) (Kanada)