Chanting Sanskrit Verses in Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda MITHUN HOWLADAR Ph. D Scholar, Department of Sanskrit, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal Received: May 22, 2018 Accepted: July 11, 2018 ABSTRACT We can generally say, any composition which has a musical sound, is called chanda. Chanda has been one of the Vedāṅgas since Vedic period. Vedic verses are composed in several chandas. The number of Vedic chandas is 21, out of which 7 are mainly used. Earliest poetic composition in public language (laukika Sanskrit) started from Valmiki, later it became a fashion and then a discipline for composition (kāvya). But here has been a difference in Vedic and laukika chandas. Where Vedic chnadas are identified by the number of syllables (varṇa or akṣara) in a line of verse or whole verse and the number of lines in the verse, laukika chanda is identified by the order of the laghu-guru syllables. The number of the laukika chandas is not yet finally defined but many texts have been composed describing the different number of chandas. Each chanda of laukika Sanskrit (post Vedic Sanskrit) consists of four pādas or caraṇas, that is, the fourth part of the chanda. Keywords: Chanda, Vedāṅgas, Chandaśāstra, pāda, Chandomañjarī. Introduction: Veda, the oldest literature in the world, is also called Chandas because the Vedic mantras (compositions) are all metric compositions (Chandobaddha). All the four Saṁhitās (with some exceptions in Yajurveda and Atharvaveda) are of this nature. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

Contribution of Leelavathi to Prosody

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 8, Ver. VI (Aug. 2015), PP 08-13 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Contribution of Leelavathi to Prosody Dr.K.K.Geethakumary Associate Professor, Dept.of Sanskrit, University of Calicut, India, Kerala, 673635) I. Introduction Leelavathi, a treatise on Mathematics, is written by Bhaskara II who lived in 12th century A.D. Besides explaining the details of mathematical concepts that were in existence up to that period, the text introduces some new mathematical concepts. This paper is an attempt to analyze the metres employed in Leelavathi as well as the concepts of permutation and combination introduced by the author in the same text. Key words:-Combination, Leelavathi, Meruprasthara, Metre, Permutation, II. Metres In The Text Leelavathi In poetry, metre has a significant role to contribute the emotive aspect. The spontaneous out pore of emotion always happens through a suitable metre that is revealed in the mind of the poet at the time of literary creation. Rhythm itself is the life of the metre as it transfuses the emotion. Varied compositions of diversified rhythms which are innumerable give birth to different metres in poetry. Early poeticians like Bhamaha, Dandin, Vamana, Rudrada and Rajasekhara have stated that erudition in prosody is essential for making poetical composition. In Vedic period, the skill of Vedic Rishis in handling the language and metre for expressing their ideas is also equally attractive. The metres used are well suited to the types of poetry, the ideas expressed in them and the content exposed. -

Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India

Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research ISSN NO: 0022-1945 Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India Ceazer Gonsalves Assistant Professor Department of English Milagres College, Udupi, Karnataka Email: [email protected] Abstract Language is a medium through which we express our thought. While the literature is a mirror which reflects ideas and philosophies which govern our society, hence to know any particular culture and its traditions it is very important we understand the evolution of its language and the various forms of literature like poetry, plan drama, religious and non religious writing. Indian language play a very important role in our culture and one of the earliest language is Sanskrit ever since human being have invented scripts, writing has reflected the culture, life style, society and the polity of the contemporary society. Each culture evolved its own language and creates a number of literary bases and this literary base of civilization tells us about the evolution of its language and culture through the span of centuries. As we know Sanskrit language is a mother of most of the Indian language .The Vedas and Puranas, Mahabharata, Ramayana all these works were written in Sanskrit language and also variety of secular and regional literature created in the past so that we can understand better. It is among the 22 language listed in the Indian Constitution .Sanskrit gave importance to study linguist scientifically during 18th and 19th century. Sanskrit is the only language that transcended the barriers of regions and boundaries from the north to the south and east to the west .There is no part of India that has not contributed to all being affected by language. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

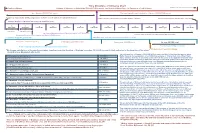

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature

YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Studia Orientalia 116 YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Helsinki 2015 Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Klaus Karttunen Studia Orientalia, vol. 116 Copyright © 2015 by the Finnish Oriental Society Editor Lotta Aunio Co-Editor Sari Nieminen Advisory Editorial Board Axel Fleisch (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Middle Eastern and Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Assyriology) Jaana Toivari-Viitala (Egyptology) Typesetting Lotta Aunio ISSN 0039-3282 ISBN 978-951-9380-88-9 Juvenes Print – Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2015 CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................... XV PART I: REFERENCES IN TEXTS A. EPIC AND CLASSICAL SANSKRIT ..................................................................... 3 1. Epics ....................................................................................................................3 Mahābhārata .........................................................................................................3 Rāmāyaṇa ............................................................................................................25 -

![History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7681/history-of-indian-philosophy-upani%C3%B1ads-key-terms-questions-pin-d%C5%93-%C3%A4%C3%BCn-aatmn-xmr-s-sar-kmr-mae-aannd-847681.webp)

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions KEY TERMS %pin;dœ *to sit down near to, to approach *the sitting down at the feet of another to listen to his words, hence, secret knowledge upaniñad *the mystery which underlies or rests underneath the external system of things Upanishad *esoteric doctrine, secret doctrine, words of mystery *a class of philosophical writings *lit. growth, expansion, evolution, swelling of the spirit or soul äün! *the sacred word, the Veda, a sacred text or Mantra (in Vedas) *the sacred syllable OM brahman *religious or spiritual knowledge brahman *the One, self-existent impersonal Spirit, universal Soul, Divine Essence and source from which all created things emanate or with which they are identified and to which they return, the Absolute, the Eternal AaTmn! *variously derived from: to breathe, to move, to blow, the breath ätman *the soul, principle of life and sensation atman *the highest personal principle of life xmR *that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, law dharma *right, justice dharma *virtue, morality, religion, religious merit, good works s<sar *going or wandering through, undergoing trasmigration *a course, passage, passing through a succession of states, circuit of mundane saàsära existence, the world, secular life, worldly illusion samsara kmR from kri, to act; thus action, performance *making, doing, performing karma (the law governing the fruit of action) karma mae] *emancipation, liberation, release mokña *release from worldly existence or transmigration, final -

A Computational Algorithm for Metrical Classification of Verse

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 7, Issue 2, No 1, March 2010 46 ISSN (Online): 1694-0784 ISSN (Print): 1694-0814 A Computational Algorithm for Metrical Classification of Verse Rama N.1 and Meenakshi Lakshmanan2 1 Department of Computer Science, Presidency College Chennai 600 005, India 2 Department of Computer Science, Meenakshi College for Women Chennai 600 024, India and Research Scholar, Mother Teresa Women’s University Kodaikanal 624 101, India Abstract other utilities for the researcher, the identification of the The science of versification and analysis of verse in Sanskrit is two aforesaid characteristics would also help even a governed by rules of metre or chandas. Such metre-wise person who is not too knowledgeable in the language and classification of verses has numerous uses for scholars and unfamiliar with the meaning of the verse, to chant the researchers alike, such as in the study of poets and their style of verse by pausing at the appropriate junctures. Sanskrit poetical works. This paper presents a comprehensive computational scheme and set of algorithms to identify the metre of verses given as Sanskrit (Unicode) or English E-text (Latin In this paper, we explore the scheme of classification of Unicode). The paper also demonstrates the use of euphonic Sanskrit prosody [5] and present computational algorithms conjunction rules to correct verses in which these conjunctions, to classify verses given either in Sanskrit Unicode font or which are compulsory in verse, have erroneously not been as English E-text. implemented. Keywords: Sanskrit, verse, hashing, metre, chandas, metrical 1.1 Unicode Representation classification, sandhi. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought.