LR003208 - Alfred Bradley (Interview 14) - No Date.Wav Duration: 0:39:10 Date: 31/07/2017 Typist: 715

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

Ideology of the Air

IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by SETH D. ASHLEY Dr. Stephanie Craft, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 presented by Seth D. Ashley a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________________________________ Professor Stephanie Craft ____________________________________________________________ Professor Tim P. Vos ____________________________________________________________ Professor Charles Davis ____________________________________________________________ Professor Victoria Johnson ____________________________________________________________ Professor Robert McChesney For Mom and Dad. Thanks for helping me explore so many different paths. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I entered the master’s program at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, my aim was to become a practitioner of journalism, but the excellent faculty members I worked with helped me aspire to become a scholar. First and foremost is Dr. Stephanie Craft, who has challenged and supported me for more than a decade. I could not have completed this dissertation or this degree without her. I was also fortunate to have early encounters with Dr. Charles Davis and Dr. Don Ranly, who opened me to a world of ideas. More recently, Dr. Tim Vos and Dr. Victoria Johnson helped me identify and explore the ideas that were most important to me. -

Made on Merseyside

Made on Merseyside Feature Films: 2010’s: Across the Universe (2006) Little Joe (2019) Beyond Friendship Ip Man 4 (2018) Yesterday (2018) (2005) Tolkien (2017) X (2005) Triple Word Score (2017) Dead Man’s Cards Pulang (2016) (2005) Fated (2004) Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2016) Alfie (2003) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Digital (2003) (2015) Millions (2003) Florence Foster Jenkins (2015) The Virgin of Liverpool Genius (2014) (2002) The Boy with a Thorn in His Side (2014) Shooters (2001) Big Society the Musical (2014) Boomtown (2001) 71 (2013) Revenger’s Tragedy Christina Noble (2013) (2001) Fast and Furious 6 John Lennon-In His Life (2012) (2000) Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit Parole Officer (2000) (2012) The 51st State (2000) Blood (2012) My Kingdom Kelly and Victor (2011) (2000) Captain America: The First Avenger Al’s Lads (2010) (2000) Liam (2000) 2000’s: Route Irish (2009) Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2009) Nowhere Fast (2009) Powder (2009) Nowhere Boy (2009) Sherlock Holmes (2008) Salvage (2008) Kicks (2008) Of Time in the City (2008) Act of Grace (2008) Charlie Noads RIP (2007) The Pool (2007) Three and Out (2007) Awaydays (2007) Mr. Bhatti on Holiday (2007) Outlaws (2007) Grow Your Own (2006) Under the Mud (2006) Sparkle (2006) Appuntamento a Liverpool (1987) No Surrender (1986) Letter to Brezhnev (1985) Dreamchild (1985) Yentl (1983) Champion (1983) Chariots of Fire (1981) 1990’s: 1970’s: Goin’ Off Big Time (1999) Yank (1979) Dockers (1999) Gumshoe (1971) Heart (1998) Life for a Life (1998) 1960’s: Everyone -

What Is a Lighting Director?

What is a lighting director by Martin Kempton What is a lighting director? Simply put - a lighting director designs the lighting for multi-camera television productions. He or she instructs the crew of electricians in their work in addition to guiding the team of operators who usually sit with the LD in the lighting control room. All this while working closely with the director and the rest of the production team to deliver the best possible pictures. However, there's rather more to it than that, and on this page on the website I explain where LDs work, what kinds of shows LDs work on and give some of the background to what we do. It's important to point out right away that simple 'illumination' is actually a relatively unimportant part of our work. Current TV cameras are capable of operating in very low light levels so it would be quite possible to see what was going on in most studios simply by switching on the houselights. Fortunately, producers and directors realise that the result would look pretty awful. Another thing is also worth making clear – a lighting director is not an electrician. He or she might have been once, but an LD is not another name for a crew chief or gaffer. Most television LDs do not have electrical qualifications, although some may have. In any case, this is not a requirement of the job. The electrical supervisor (gaffer) is in charge of realising the LD’s design in the studio from the rigging and electrical point of view. -

Has TV Eaten Itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

May 2015 Has TV eaten itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT Hosted by Romesh Ranganathan. Nominated films and highlights of the awards ceremony will be broadcast by Sky www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2015 l Volume 52/5 From the CEO The general election are 16-18 September. I am very proud I’d like to thank everyone who has dominated the to say that we have assembled a made the recent, sold-out RTS Futures national news agenda world-class line-up of speakers. evening, “I made it in… digital”, such a for much of the year. They include: Michael Lombardo, success. A full report starts on page 23. This month, the RTS President of Programming at HBO; Are you a fan of Episodes, Googlebox hosts a debate in Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom; David or W1A? Well, who isn’t? This month’s which two of televi- Abraham, CEO at Channel 4; Viacom cover story by Stefan Stern takes a sion’s most experienced anchor men President and CEO Philippe Dauman; perceptive look at how television give an insider’s view of what really Josh Sapan, President and CEO of can’t stop making TV about TV. It’s happened in the political arena. AMC Networks; and David Zaslav, a must-read. Jeremy Paxman and Alastair Stew- President and CEO of Discovery So, too, is Richard Sambrook’s TV art are in conversation with Steve Communications. Diary, which provides some incisive Hewlett at a not-to-be missed Leg- Next month sees the 20th RTS and timely analysis of the election ends’ Lunch on 19 May. -

265 June 2019 Web Hi-Res.Pub

Formby U3A Newsletter June 2019 Formby U3A, Reg. Charity No. 1161157 Harewood House Author, Pam Skelton; photos David Skelton. What a glorious day! Although a bit grey when we left Formby, by the time we reached Hartshead Moor service station the sun was clear of all its clouds. That of course was only a short comfort stop and we soon back on the M62 en-route for Harewood. Travelling through a built-up area, I was astonished to discover that "Pudsey" is a place, not just the name of a Contents Page yellow bear with a spotty eye patch. We live Anyone for Ping Pong? 3 and learn don't we? Fulwood Barracks 3 On arrival at Harewood House Ann had organised all entrance tickets so the rest of us Golf 5 could just stay on the bus (a very comfortable Group News 7 one) until, well within the grounds, we Harewood House 1 disembarked and began our day proper. Ann had also arranged that we be met with tea/ Monthly Meetings 12 coffee and biscuits in a private room in the Music and Theatre Events 11 former stable block, which was very welcome. The biscuits were homemade and of various New Members 10 flavours, chocolate chip, ginger and plain Outings Group 8 among them. Our cups were cheerfully refilled Royal Liver Building 5 as often as wanted and the whole atmosphere was welcoming and bright. Then we had to NW Region U3A Big Sing 4 make a choice - to start in the house or in the www.formbyu3a.org.uk 2 gardens? David and I chose the house and walked up the path to the grand entrance, although we could have taken the free shuttle bus from the courtyard and others enjoyed this more leisurely way. -

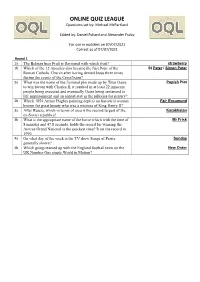

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions Set By: Michael Mcpartland

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by: Michael McPartland Edited by: Daniel Fullard and Alexander Furby For use in matches on 07/07/2021 Correct as of 07/07/2021 Round 1 1a The Belgian beer Fruli is flavoured with which fruit? strawberry 1b Which of the 12 Apostles also became the first Pope of the St Peter / Simon Peter Roman Catholic Church after having denied Jesus three times during the events of the Crucifixion? 2a What was the name of the fictional plot made up by Titus Oates Popish Plot to win favour with Charles II, it resulted in at least 22 innocent people being executed and eventually Oates being sentenced to life imprisonment and an annual stay in the pillories for perjury? 2b Which 1854 Arthur Hughes painting depicts an historical woman Fair Rosamund known for great beauty who was a mistress of King Henry II? 3a After Russia, which in terms of area is the second largest of the Kazakhstan ex-Soviet republics? 3b What is the appropriate name of the horse which with the time of Mr Frisk 8 minutes and 47.8 seconds, holds the record for winning the Aintree Grand National is the quickest time? It set the record in 1990. 4a On what day of the week is the TV show Songs of Praise Sunday generally shown? 4b Which group teamed up with the England football team on the New Order UK Number One single World in Motion? Round 2 1a Which solo artist became a one hit wonder in 1994, with the Tony Di Bart number one single The Real Thing? 1b Which actresses’ TV roles include playing Megan Roberts the Nerys Hughes titular character in the 1980s drama series The District Nurse and Sandra Hutchinson, one of the two title characters, alongside Polly James in the 1970s comedy series The Liver Birds? 2a What 28 letter long word is given to the position that advocates antidisestablishmentarianism that the established state church should continue to receive government patronage and should not become unrecognised as the state’s official religion? 2b The actress Stella Banderas is one of the daughters of Melanie Dakota Johnson Griffith. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Verguson, Christine Jane ‘Opting out’? nation, region and locality Original Citation Verguson, Christine Jane (2014) ‘Opting out’? nation, region and locality. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/23523/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ ‘OPTING OUT’? NATION, REGION AND LOCALITY The BBC in Yorkshire 1945-1990 CHRISTINE JANE VERGUSON A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield January 2014 Copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Russia and Allofmp3.Com: Why the WTO and WIPO Must Create a New System for Resolving Copyright Disputes in the Digital Age Brian A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Intellectual Property Journal Akron Law Journals March 2016 Russia and Allofmp3.com: Why The WTO And WIPO Must Create a New System for Resolving Copyright Disputes in The Digital Age Brian A. Benko Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronintellectualproperty Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Benko, Brian A. (2007) "Russia and Allofmp3.com: Why The WTO And WIPO Must Create a New System for Resolving Copyright Disputes in The Digital Age," Akron Intellectual Property Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronintellectualproperty/vol1/iss2/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Intellectual Property Journal by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Benko: Resolving Copyright Disputes in the Digital Age RUSSIA AND ALLOFMP3.COM: WHY THE WTO AND WIPO MUST CREATE A NEW SYSTEM FOR RESOLVING COPYRIGHT DISPUTES IN THE DIGITAL AGE Even when laws have been written down, they ought not always remain unaltered. Aristotle' I. INTRODUCTION The Digital Age threatens copyright protection throughout the world.2 Computer file formats, such as the MP3,3 allow music owners to make an intangible copy of their music library.4 In the 1990s, Peer-to- Peer ("P2P") file sharing networks exploited this new technology.5 These networks created a way for users to download songs without pay- 1. -

John of Salisbury's Relics of Saint Thomas Becket and Other Holy Martyrs 163

Aus dem Inhalt der folgenden Bände: Band 26 2013 Reinhard Bleck, Reinmar der Alte, Lieder mit historischem Hintergrund 2013 (MF 156,10; 167,31; 180,28; 181,13) · Dina Aboul Fotouh Salama, Die Kolonialisierung des weiblichen Körpers in der spätmittelalterlichen Versnovelle „Die heideninne“ Internationale Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Mittelalterforschung Band 26 Werner Heinz, Heilige Längen: Zu den Maßen des Christus- und des Mariengrabes in Bebenhausen George Arabatzis, Nicephoros Blemmydes’ Imperial Statue: Aristotelian Politics as Kingship Morality in Byzantium Francesca Romoli, La funzione delle citazioni bibliche nell'omiletica e nella letteratura di direzione spirituale del medioevo slavo orientale (XII-XIII sec.) Connie L. Scarborough, Educating Women for the Benefit of Man and Society: Castigos y dotrinas que un sabio daba a sus hijas and La perfecta casada Beihefte zur Mediaevistik: Elisabeth Mégier, Christliche Weltgeschichte im 12. Jahrhundert: Themen, Variationen und Kontraste. Untersuchungen zu Hugo von Fleury, Orderi- cus Vitalis und Otto von Freising (2010) Andrea Grafetstätter / Sieglinde Hartmann / James Ogier (eds.), Islands and Cities in Medieval Myth, Literature, and History. Papers Delivered at the International Medieval Congress, University of Leeds, in 2005, 2006, and 2007 (2011) Olaf Wagener (Hrsg.), „vmbringt mit starcken turnen, murn“. Ortsbefesti- gungen im Mittelalter (2010) Hiram Kümper (Hrsg.), eLearning & Mediävistik. Mittelalter lehren und lernen im neumedialen Zeitalter (2011) Begründet von Peter Dinzelbacher -

If You Missed the FBLA Meeting Yesterday, Please See Mrs. Angle in Room B1 Today to Pick up Information for Your Region Competition

Today’s Statistics: Thursday, November 14, 2019 Marking Period: 1 of 4 Student Day: 56 of 180 Snow Days Used: Not Yet Today’s Weather: 26° Sunny SW wind 8-11mph If you missed the FBLA meeting yesterday, please see Mrs. Angle in Room B1 today to pick up information for your region competition. Any student interested in taking a fan bus to Hazleton for Friday’s state playoff game, please sign up with Mrs. Mandzy in the 11/12 office. Please bring $4 for your ticket to the game. A minimum of 25 students is needed to run the bus, so sign up ASAP. Sign-ups will end Thursday afternoon. Attention 9th and 10th grade students: Be sure to report to the auditorium 3rd period for an assembly. Any student interested in taking a fan bus to Hazleton for Friday’s state playoff game, please sign up with Mrs. Mandzy in the 11/12 office. Please bring $4 for your ticket to the game. A minimum of 25 students is needed to run the bus, so sign up ASAP. Sign-ups will end Thursday afternoon. Attention FBLA members, volunteers are needed for the Turkey Trot on November 16. Sign- up sheets are on bulletin boards outside of Rooms S5 and B1. Basketball Cheerleading Tryouts will be held on Monday, November 18th from 3:00-6:00 in the 9/10 cafeteria. Pick up atryout packet from Coach Marchetti in the Green Gym outside the girls locker room. You must have a physical dated after June 1, 2019 to try out. -

History of the BBC October 1922

9/9/2019 1920s - History of the BBC Home News Sport Weather Shop Reel Travel Capital M History of the BBC Menu 1920s Where it all began, turning early radio experiments into a new medium - broadcasting. 1920s The British Broadcasting Company, as the BBC was originally called, was formed on 18 October 1922 by a group of leading wireless manufacturers including Marconi. Daily broadcasting by the BBC began in Marconi's London studio, 2LO, in the Strand, on November 14, 1922. John Reith, a 33-year-old Scottish engineer, was appointed General Manager of the BBC at the end of 1922. October 1922 - 2LO launched Following the closure of numerous amateur stations, the BBC started its first daily radio service in London – 2LO. Aer much argument, news was supplied by an agency, and music drama and 'talks' filled the airwaves for only a few hours a day. It wasn't long before radio could be heard across the nation. https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/timelines/1920s 1/7 9/9/2019 1920s - History of the BBC Pathe News marks the start of 2LO in a cinema newsreel. December 1922 - John Reith appointed Thirty-three year old John Charles Walsham Reith became General Manager of the BBC on 14 December 1922. I hadn't the remotest idea as to what broadcasting was. There were no rules, standards or established purpose to guide him. He immediately began innovating, experimenting and organising, and with the help of his newly appointed chief engineer, Peter Eckersley, the service began to expand. https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/timelines/1920s 2/7 9/9/2019 1920s - History of the BBC John Reith September 1923 - Radio Times first edition The first edition of The Radio Times listed the few programmes on offer.