Missions, Their Rise and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Henry Martyn to the Study of India's Muslims and Islam in the Nineteenth Century

THE LEGACY OF HENRY MARTYN TO THE STUDY OF INDIA'S MUSLIMS AND ISLAM IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Avril A. Powell University of Lincoln (SOAS) INTRODUCTION: A biography of Henry Martyn, published in 1892, by George Smith, a retired Bengal civil servant, carried two sub-titles: the first, 'saint and scholar', the second, the 'first modern missionary to the Mohammedans. [1]In an earlier lecture we have heard about the forming, initially in Cambridge, of a reputation for spirituality that partly explains the attribution of 'saintliness' to Martyn: my brief, on the other hand, is to explore the background to Smith's second attribution: the late Victorian perception of him as the 'first modern missionary' to Muslims. I intend to concentrate on the first hundred years since his ordination, dividing my paper between, first, Martyn's relations with Muslims in India and Persia, especially his efforts both to understand Islam and to prepare for the conversion of Muslims, and, second, the scholarship of those evangelicals who continued his efforts to turn Indian Muslims towards Christianity. Among the latter I shall be concerned especially with an important, but neglected figure, Sir William Muir, author of The Life of Mahomet, and The Caliphate:ite Rise, Decline and Fall, and of several other histories of Islam, and of evangelical tracts directed to Muslim readers. I will finish with a brief discussion of conversion from Islam to Christianity among the Muslim circles influenced by Martyn and Muir. But before beginning I would like to mention the work of those responsible for the Henry Martyn Centre at Westminster College in recently collecting together and listing some widely scattered correspondence concerning Henry Martyn. -

My Pilgrimage in Mission Michael C

My Pilgrimage in Mission Michael C. Griffiths was born in Cardiff, Wales, in April 1928. A simple CICCU was seeing students converted every week; of the five Icalculation shows that like others of my generation I have hundred members, half were converted after joining the univer- lived through a third of the history of Anglo-Saxophone mission, sity. After two terms I was invited onto the Executive Committee, giving an interesting perspective upon it. and in my second year became president of this indigenous At age ten I won a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital, a boys student movement, run by and for students. At age twenty-three, boarding school, founded as a Reformation response to the need this experience provided remarkable on-the-job training. The of London’s street children. Then two weeks after World War II following two years I served as missionary secretary, and then started, I began attending the school’s Christian Union, a group chairman, of the national InterVarsity Fellowship (IVF) Student indigenous to and organized by senior schoolboys. After four Executive, covering twenty-two universities in the United King- years of Sunday meetings, I came to Christ through Alfred dom (now fifty years later there are five times as many). As well Schultes, a German pastor of the Confessing Church. We boys as seeing many conversions through student evangelism, two listened to this “enemy” because he had suffered, having been other things accelerated my pilgrimage. imprisoned by Hitler with Martin Niemöller and later interned In my first term the CICCU was organized into forty mission by us. -

The Legacy of Thomas Valpy French

The Legacy of Thomas Valpy French Vivienne Stacey ew seem to have heard of this self-effacing man, Thomas service abroad. Soon after this Lea was fatally injured in a railway F Valpy French. However, Bishop Stephen Neill described accident. Their mutual decision bound French even more and he him as the most distinguished missionary who has ever served applied to the CMS. the Church Missionary Society (CMS).1 For those concerned with There was one other matter to be resolved before he and his communicating the gospel to Muslims, his legacy is especially companion, Edward Stuart, sailed in 1850 for India. Thomas was precious. attracted to M. A. Janson, daughter of Alfred Janson of Oxford. Twice her parents refused permission to Thomas to pursue his The Life of French (1825-1891) suit even by correspondence. According to the custom of the day, he accepted this, though very reluctantly.i Then suddenly Alfred Thomas Valpy French was born on New Year's Day 1825, the Janson withdrew his objections and Thomas was welcomed by first child of an evangelical Anglican clergyman, Peter French, the family. He became engaged to the young woman shortly who worked in the English Midlands town of Burton-on-Trent before he sailed." A year later she sailed to India to be married for forty-seven years. In those days before the Industrial Revo to him. Throughout- his life, she was a strong, quiet support to lution, Burton-on Trent was a small county town. Thomas liked him. The health and educational needs of their eight children walking with his father to the surrounding villages where Peter sometimes necessitated long periods of separation for the parents. -

Biography of Thomas Valpy French

THOMAS VALPY FRENCH, FIRST BISHOP OF LAHORE By Vivienne Stacey CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introductory – Burton- on-Trent, Lahore, Muscat 2 Chapter 2 Childhood, youth and. early manhood 10 Chapter 3 The voyage, first impressions, St. John’s College Agra 16 Chapter 4 Agra in the 1850’s 25 Chapter 5 French’s first furlough and his first call to the Dejarat 36 Chapter 6 Six years in England, 1863-1869 46 Chapter 7 St. John’s Divinity School, Lahore 55 Chapter 8 The creation of’ the Diocese at Lahore 69 Chapter 9 The building of the Cathedral of the Resurrection, Lahore 75 Chapter 10 The first Bishop of Lahore 1877 – 1887 84 Chapter 11 Resignation. Journey to England through the Middle East 97 Chapter 12 Call to Arabia and death in Muscat 108 Some important dates 121 Bib1iography primary sources 122 secondary sources 125 1 Chapter 1: Introductory. Burton-on Trent, Lahore, Muscat Three thousand or so Pakistanis are camped in the half-built town of Salalah in the Sultanate of Oman. They are helping to construct the second largest city of Oman – most of them live in tents or huts. Their size as a community is matched by the Indian commu- nity also helping in this work and in the hospital and health pro- grammes. Among the three thousand Pakistanis perhaps three hundred belong to the Christian community. Forty or so meet for a service of worship every Friday evening – they are organized as a local congregation singing psalms in Punjabi and hearing the Holy Bible expounded in Urdu. -

Sunday 31 May Pentecost the Bishop: Pray for Archbishop Michael And

Sunday Pentecost The Bishop: Pray for Archbishop Michael and for his oversight of the 31 May Diocese and the Province. Kuwait: The Anglican Church in Kuwait, St Paul’s, has three - English, Urdu and Mandarin - congregations. There are three English worship services in a week and two of them are held at Ahmadi on Thursdays, Fridays and Sundays. The Centre hosts nineteen other congregations. Monday We praise God for keeping the congregation together during this time of the Coronavirus 1 despite not being able to physically meet. Tuesday We rejoice in the joy of having our people maintaining contacts and attendance of services 2 via livestreaming using ZOOM. Four other meetings are conducted weekly with encouraging participation. Wednesday We are hopeful of returning to the church and worship in our space and to see life 3 returning to normalcy for all the people. Thursday We seek God’s intervention for our depleting financial resources, as this ultimately affects 4 our budget. Jobs are insecure for our members especially due to the Covid - 19 pandemic. Friday The future is uncertain. We pray for our parishioners to remain positive, committed, and 5 dedicated amidst current challenges. Saturday Heavenly Father, we are delighted to experience your love. Give us hope and trust in you 6 amid challenges we encounter as a parish. Inspire your people to be thankful to you for all your grace and divine protection. Continue to bless the goodwill we receive from the State of Kuwait and other stakeholders and bring more people to our fellowship. Amen. Sunday Trinity Sunday Those being confirmed: Pray for all considering or preparing for 7 June Confirmation, that the Spirit will guide them. -

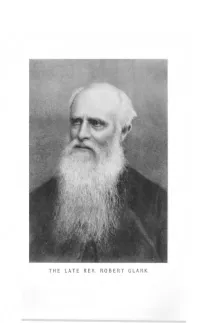

The Late Rev. Robert Clark. the Missions

THE LATE REV. ROBERT CLARK. THE MISSIONS OF THE CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY A~D THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND ZENANA MISSIONARY · SOCIETY IN THE PUNJAB AND SINDH BY THE LATE REv. ROBERT CLARK, M.A. EDITED .AND REPISED BY ROBERT MACONACHIE, LATE I.C.S. LONDON: CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY SALi SBU R Y SQUARE, E.C. 1904 PREFATORY NOTE. --+---- THE first edition of this book was published in 18~5. In 1899 Mr. Robert Clark sent the copy for a second and revised edition, omitting some parts of the original work, adding new matter, and bringing the history of the different branches of the Mission up to date. At the same time he generously remitted a sum of money to cover in part the expense of the new edition. It was his wish that Mr. R. Maconachie, for many years a Civil officer in the Punjab, and a member of the C.M.S. Lahore Corre sponding Committee, would edit the book; and this task Mr. Maconachie, who had returned to England and was now a member of the Committee at home, kindly undertook. Before, however, he could go through the revised copy, Mr. Clark died, and this threw the whole responsibility of the work upon the editor. Mr. Maconachie then, after a careful examination of the revision, con sidered that the amount of matter provided was more than could be produced for a price at which the book could be sold. He therefore set to work to condense the whole, and this involved the virtual re-writing of some of the chapters. -

THE NEARER and FARTHER EAST," Consists of Two Parts, - " Moslem Lands," by Rev

aM'" illS ntA-.IJ:i8''FUl IU II.,..],"'" !If' II IF .."'..........., M lfU!lQliill'.-"-- ' ......iGii;· THE NEARERAND · FA,RT,HER EAST OUTLINE STUDIES OF MOSLEM LANDS A'N'D OF SIAM BUR.MA. AND KOREA SAMUEL 'I'll tb Z'WEMER" .A.ND ARTHU'R.. r&J. BR..O"W'N electronic file created by cafis.org .T~. -3 0 THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO ATLANTA' SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., LIMITED LONDON • BOMBAV • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO electronic file created by cafis.org 120 20 o 100 A RUS J I I~IA. 40 ____-120 BA.BIA.N qE.J. .. :~ c:' fQUATOR 0 • .0' I N JJ I A N .,' ". 0 C E A N 1V.Iap sho-..ving; 'thE' \--------cri"'~------_J20 20 I-t-------- PRESENT EXTENT OF ISLAllI /1 ',"" __ ..:= L._ With !I,,,,..tlOll "r p.ln"lllul MI••I"n Stations ---- -1-- "-- """~--~---"~ to ""..ell. M.oslems Mosfem Population or Infll.\ence ----------.c=J AUSTRALIA Pagan Tribes . -'" ~ .... Direction of Mosrem Advance ~ __ ~~"" ~ ~~in.cipal Misslon Sta.ti<H... S~ ._ __B~.y 120 20 Longitude We.t o Longitude 20 East frOln 40 Gr-eenwich 60 so 100 CopyrIght, '907, by Student VolunlL'er Movement for Foreign Missions. electronic file created by cafis.org THE NEARER A.ND FARTHER EAST OUTLINE STUDIES OF MOSLEM: LANDS AND OF SIAM, BURMA, AND KOREA BY SAMUEL M. ZWEMER, F.R.G.S. AND ARTHUR JUDSON BROWN, D.D. NtiD m{Jtk THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1908 electronic file created by cafis.org COPYRIGHT, 1908, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. -

November 2014

Parish of St. David with St. Michael Directory 2014 Vicar Tom Honey 686 000 & 07837 867 680 Assistant Curate ~ ~ Parish Missioner Simon Harrison 07824 456 938 Churchwarden Avril Pattinson 860 880 “ Dave Allin ~ Reader Bill Pattinson 860 880 PCC Secretary Mary Kirkland 980 660 Parish Treasurer Adrian Hewitt 437 313 Electoral Roll Officer Jeremy Lawford 214 025 Thika Link Kate Bray 877 162 St. David’s www.stdavidschurchexeter.org.uk Treasurer Barbara Allin 270 162 Asst. Treasurer Geoff Crockett 468 073 Choir Nigel Walsh 273 237 News Sheet Helena Walker [email protected] Toddler Group Julia Spruntulis 270 986 Junior Church Bill Pattinson 860 880 Servers Christopher Smith 259 469 Church Bookings Mary Quest 07792 062 403 Readers & Avril Pattinson 860 880 Time of Prayer Rota St Michael's www.stmichaelsmountdinham.org.uk Hon Asst Priest John Thurmer 272 277 Hon Asst Priest David Hastings 498 233 Chapel Warden Richard Parker ~ Chapel Warden George Hexter 469 479 Treasurer Adrian Hewitt 437 313 News Sheet Lis Robins 239389 Secretary Elizabeth Hewitt 437 313 Director of Music Alex West [email protected] Organist Nigel Browne 01363 881 137 Magazine Advertising Glynis Harflett 214 787 [email protected] Designers Ashley Potter & 432 911 Joh Ryder [email protected] ST FRANCIS Last month at St David’s we celebrated Francis of Assisi on his feast day. Bill Pattinson preached a fascinating sermon about Francis and his radi- cal renunciation of worldly goods. Bill also recounted the story about St Francis praying in the derelict church of San Damiano. He clearly heard a voice coming from the crucifix, saying to him, “Francis, rebuild my house which you can see is falling down.” At first Francis took this command literally. -

Mission and Meaning Essays Presented to Peter Cotterell

Mission and Meaning Essays Presented to Peter Cotterell Edited by Antony Billington Tony Lane Max Turner Carlisle: Paternoster Press, 1995. ISBN: 0-85364-676-7 © The Editors and Contributers 1995 Reproduced by kind permission of Paternoster Press Prepared for the Web in September 2009 by Robert I Bradshaw https://theologyontheweb.org.uk 10 A Model Missionary to Muslims: Thomas Valpy French (1825-1891) Michael Griffiths 1. Introduction The subject of this essay was a deeply committed missionary to Muslims, regarded in his own day as stoical to a fault, and who would today be labelled as a 'workaholic'. Such qualities will appeal to Peter Cotterell, himself an indefatigable worker. At the same time, I am conscious that for Peter, the contemporary thrust, where we are now, and even more where we ought to be soon, must always be more important than an antiquarian interest in where missions used· to be. We deplqre a common result of reading nineteenth century hagiography, that people imagine mission to be as it was then, rather than as it is now. It could be argued, however, that Valpy French was making more progress with Muslims than many of us are today, and that his approaches may give us a useful paradigm for pioneer situations still. It is not only over-enthusiastic biographers who can be selective with truth: some classic mission histories give us a one sided picture - Stephen Neill, for instance, in his Penguin history, regards only one or two Christian women as worthy of mention by name, and gives little space to American interdenominational, as compared with European ecumenical mission agencies. -

Islam in European Thought

Islam in European Thought ALBERT HOURANI THE TANNER LECTURES ON HUMAN VALUE Delivered at Clare Hall, Cambridge University January 30 and 31 and February 1, 1989 ALBERT HOURANI was born in Manchester, England, in 1915 and studied at Oxford University. He taught the modern history of the Middle East at Oxford until his retirement, and is an Emeritus Fellow of St. Antony’s College and Honorary Fellow of Magdalen College. He has been a visiting professor at the American University of Beirut, the Universities of Chicago and Pennsylvania, and Harvard University, and Distinguished Fellow in the Humanities at Dartmouth College. His books include Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age (1962 ; revised edition, 1983)) Europe and the Middle East (1980), and The Emergence of the Modern Middle East (1981). I From the time it first appeared, the religion of Islam was a problem for Christian Europe. Those who believed in it were the enemy on the frontier. In the seventh and eighth centuries armies fighting in the name of the first Muslim empire, the Caliphate, expanded into the heart of the Christian world. They occupied provinces of the Byzantine Empire in Syria, the Holy Land, and Egypt, and spread westward into North Africa, Spain, and Sicily; and the conquest was not only a military one but was followed in course of time by conversions to Islam on a large scale. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries there was a Christian counter- attack, successful for a time in the Holy Land, where a Latin king- dom of Jerusalem was created, and more permanently in Spain. -

2019 Yearbook

— THE LIVING STONES OF THE HOLY LAND TRUST _________________________________________________ Registered Charity No. 1081204 'An ecumenical trust seeking to promote contacts between Christian Communities in Britain and those in the Holy Land and neighbouring countries.’ You are permitted to redistribute or reproduce all or part of the contents of the Yearbook in any form as long as it is for personal or academic purposes and non-commercial use only and that you acknowledge and cite appropriately the source of the material. You are not permitted to distribute or commercially exploit the content without the written permission of the copyright owner, nor are you permitted to transmit or store the content on any other website or other form of electronic retrieval system. The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of the contents in its publications. However, the opinions and views expressed in its publications are those of the contributors and are not necessarily those of The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust. The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook and its content are copyright of © The Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust. All rights reserved. [email protected] 1 Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2019 2 Contributors Living StoneS Yearbook 2019 i Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2017-18 ii Contributors Living StoneS Yearbook 2019 Witness and Communion: Christian Theological and Political Thought in the Contemporary Middle East Living StoneS of the hoLY Land truSt Registered charity no. 1081204 iii Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust Yearbook 2017-18 © Living Stones of the Holy Land Trust 2019 all rights reserved. -

The Legacy of Karl Gottlieb Pfander

Protestant Christianity in East Asia (China, Japan, and Korea). expansion of the church in many Third World regions, makes This project has brought me full circle back to some of the little impression on it. unanswered questions from my earlier missionary days in the Ecumenicalconferencesissuestatementssuchas "theChurch Far East. on earth is missionary by its very nature" (Ad Gentes 2), but I wonder about their usefulness, considering the minimal impact Challenges of Missiology such slogans have on programs for ministerial training and on priorities of local congregations. Only as the church in the West It had always struck me that the teaching of missions had no is fully engaged in evangelization in its own neighborhood will clearly defined or adequate place in the theological curriculumof it be ready to take its partin God's mission at the endsof the earth. mainline seminaries. Whatever place it once had seems to have Work at the academic edges and on the literary fringes of further diminished in recent years. This lack of status contrasts missiology has constituted my major involvement in the mission sharply with the central place of mission in the New Testament of Jesus Christin recentyears. YetI have always felt mostat home and in the early church, and it contradicts the growing recogni when visiting new congregations in China, inspecting village tion given to mission and evangelism by ecumenical assemblies projects in India, or greeting local groups of believers in Africa. and by theological education programs in the Third World. With God's people, I rejoice that the mission of God has It seems to me that the dominant Western model of theologi entered a newphaseas Christians in 11.011.-Westernlandsembrace cal education is one devised in the late period of Christendom.