Proposal to Encode the Kaithi Script in ISO/IEC 10646

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet

- ON THE <)|{I<; IN <>F TIIK INDIAN BRAHMA ALPHABET GEORG BtfHLKi; SECOND REVISED EDITION OF INDIAN STUDIES, NO III. TOGETHER WITH TWO APPENDICES ON THE OKU; IN OF THE KHAROSTHI ALPHABET AND OF THK SO-CALLED LETTER-NUMERALS OF THE BRAHMI. WITH TIIKKK PLATES. STRASSBUKi-. K A K 1. I. 1 1M I: \ I I; 1898. I'lintccl liy Adolf Ilcil/.haiisi'ii, Vicniiii. Preface to the Second Edition. .As the few separate copies of the Indian Studies No. Ill, struck off in 1895, were sold very soon and rather numerous requests for additional ones were addressed both to me and to the bookseller of the Imperial Academy, Messrs. Carl Gerold's Sohn, I asked the Academy for permission to issue a second edition, which Mr. Karl J. Trlibner had consented to publish. My petition was readily granted. In addition Messrs, von Holder, the publishers of the Wiener Zeitschrift fur die Kunde des Morgenlandes, kindly allowed me to reprint my article on the origin of the Kharosthi, which had appeared in vol. IX of that Journal and is now given in Appendix I. To these two sections I have added, in Appendix II, a brief review of the arguments for Dr. Burnell's hypothesis, which derives the so-called letter- numerals or numerical symbols of the Brahma alphabet from the ancient Egyptian numeral signs, together with a third com- parative table, in order to include in this volume all those points, which require fuller discussion, and in order to make it a serviceable companion to the palaeography of the Grund- riss. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION ’ P”(Bha.t.tikāvya) is one of the boldest “B experiments in classical literature. In the formal genre of “great poem” (mahākāvya) it incorprates two of the most powerful Sanskrit traditions, the “Ramáyana” and Pánini’s grammar, and several other minor themes. In this one rich mix of science and art, Bhatti created both a po- etic retelling of the adventures of Rama and a compendium of examples of grammar, metrics, the Prakrit language and rhetoric. As literature, his composition stands comparison with the best of Sanskrit poetry, in particular cantos , and . “Bhatti’s Poem” provides a comprehensive exem- plification of Sanskrit grammar in use and a good introduc- tion to the science (śāstra) of poetics or rhetoric (alamk. āra, lit. ornament). It also gives a taster of the Prakrit language (a major component in every Sanskrit drama) in an easily ac- cessible form. Finally it tells the compelling story of Prince Rama in simple elegant Sanskrit: this is the “Ramáyana” faithfully retold. e learned Indian curriculum in late classical times had at its heart a system of grammatical study and linguistic analysis. e core text for this study was the notoriously difficult “Eight Books” (A.s.tādhyāyī) of Pánini, the sine qua non of learning composed in the fourth century , and arguably the most remarkable and indeed foundational text in the history of linguistics. Not only is the “Eight Books” a description of a language unmatched in totality for any language until the nineteenth century, but it is also pre- sented in the most compact form possible through the use xix of an elaborate and sophisticated metalanguage, again un- known anywhere else in linguistics before modern times. -

GEO ROO DIST BUC PRO Prep ATE 111 Cha Dec Expi OTECHNICA OSEVELT ST TRICT CKEYE, ARI OJECT # 15 Pared By

GEOTECHNICAL EXPLORARATION REPORT ROOSEVELT STREET IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT BUCKEYE, ARIZONA PROJECT # 150004 Prepared by: ATEK Engineering Consultants, LLC 111 South Weber Drive, Suite 1 Chandler, Arizona 85226 Exp ires 9/30/2018 December 14, 2015 December 14, 2015 ATEK Project #150004 RITOCH-POWELL & Associates 5727 North 7th Street #120 Phoenix, AZ 85014 Attention: Mr. Keith L. Drunasky, P.E. RE: GEOTECHNICAL EXPLORATION REPORT Roosevelt Street Improvement District Buckeye, Arizona Dear Mr. Drunasky: ATEK Engineering Consultants, LLC is pleased to present the attached Geotechnical Exploration Report for the Roosevelt Street Improvement Disstrict located in Buckeye, Arizona. The purpose of our study was to explore and evaluate the subsurface conditions at the proposed site to develop geotechnical engineering recommendations for project design and construction. Based on our findings, the site is considered suittable for the proposed construction, provided geotechnical recommendations presented in thhe attached report are followed. Specific recommendations regarding the geotechnical aspects of the project design and construction are presented in the attached report. The recommendations contained within this report are depeendent on the provisions provided in the Limitations and Recommended Additional Services sections of this report. We appreciate the opportunity of providing our services for this project. If you have questions regarding this report or if we may be of further assistance, please contact the undersigned. Sincerely, ATEK Engineering Consultants, LLC Expires 9/30/2018 James P Floyd, P.E. Armando Ortega, P.E. Project Manager Principal Geotechnical Engineer Expires 9/30/2017 111 SOUTH WEBER DRIVE, SUITE 1 WWW.ATEKEC.COM P (480) 659-8065 CHANDLER, AZ 85226 F (480) 656-9658 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

A Practical Sanskrit Introductory

A Practical Sanskrit Intro ductory This print le is available from ftpftpnacaczawiknersktintropsjan Preface This course of fteen lessons is intended to lift the Englishsp eaking studentwho knows nothing of Sanskrit to the level where he can intelligently apply Monier DhatuPat ha Williams dictionary and the to the study of the scriptures The rst ve lessons cover the pronunciation of the basic Sanskrit alphab et Devanagar together with its written form in b oth and transliterated Roman ash cards are included as an aid The notes on pronunciation are largely descriptive based on mouth p osition and eort with similar English Received Pronunciation sounds oered where p ossible The next four lessons describ e vowel emb ellishments to the consonants the principles of conjunct consonants Devanagar and additions to and variations in the alphab et Lessons ten and sandhi eleven present in grid form and explain their principles in sound The next three lessons p enetrate MonierWilliams dictionary through its four levels of alphab etical order and suggest strategies for nding dicult words The artha DhatuPat ha last lesson shows the extraction of the from the and the application of this and the dictionary to the study of the scriptures In addition to the primary course the rst eleven lessons include a B section whichintro duces the student to the principles of sentence structure in this fully inected language Six declension paradigms and class conjugation in the present tense are used with a minimal vo cabulary of nineteen words In the B part of -

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-04-22 Document version: 2.7 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract This document lays down the Label Generation Ruleset for Gurmukhi script. Three main components of the Gurmukhi Script LGR i.e. Code point repertoire, Variants and Whole Label Evaluation Rules have been described in detail here. All these components have been incorporated in a machine-readable format in the accompanying XML file named "proposal-gurmukhi-lgr-22apr19-en.xml". In addition, a document named “gurmukhi-test-labels-22apr19-en.txt” has been provided. It provides a list of labels which can produce variants as laid down in Section 6 of this document and it also provides valid and invalid labels as per the Whole Label Evaluation laid down in Section 7. 2. Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Guru ISO 15924 Key N°: 310 ISO 15924 English Name: Gurmukhi Latin transliteration of native script name: gurmukhī Native name of the script: ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ Maximal Starting Repertoire [MSR] version: 4 1 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1. The Evolution of the Script Like most of the North Indian writing systems, the Gurmukhi script is a descendant of the Brahmi script. The Proto-Gurmukhi letters evolved through the Gupta script from 4th to 8th century, followed by the Sharda script from 8th century onwards and finally adapted their archaic form in the Devasesha stage of the later Sharda script, dated between the 10th and 14th centuries. -

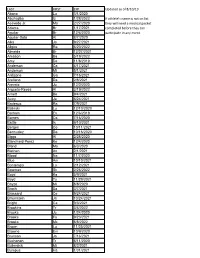

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

Kharosthi Manuscripts: a Window on Gandharan Buddhism*

KHAROSTHI MANUSCRIPTS: A WINDOW ON GANDHARAN BUDDHISM* Andrew GLASS INTRODUCTION In the present article I offer a sketch of Gandharan Buddhism in the centuries around the turn of the common era by looking at various kinds of evidence which speak to us across the centuries. In doing so I hope to shed a little light on an important stage in the transmission of Buddhism as it spread from India, through Gandhara and Central Asia to China, Korea, and ultimately Japan. In particular, I will focus on the several collections of Kharo~thi manuscripts most of which are quite new to scholarship, the vast majority of these having been discovered only in the past ten years. I will also take a detailed look at the contents of one of these manuscripts in order to illustrate connections with other text collections in Pali and Chinese. Gandharan Buddhism is itself a large topic, which cannot be adequately described within the scope of the present article. I will therefore confine my observations to the period in which the Kharo~thi script was used as a literary medium, that is, from the time of Asoka in the middle of the third century B.C. until about the third century A.D., which I refer to as the Kharo~thi Period. In addition to looking at the new manuscript materials, other forms of evidence such as inscriptions, art and architecture will be touched upon, as they provide many complementary insights into the Buddhist culture of Gandhara. The travel accounts of the Chinese pilgrims * This article is based on a paper presented at Nagoya University on April 22nd 2004. -

2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, As Required Under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code Section 68563 HON

JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF CALIFORNIA 455 Golden Gate Avenue May 15, 2020 San Francisco, CA 94102-3688 Tel 415-865-4200 TDD 415-865-4272 Fax 415-865-4205 www.courts.ca.gov Hon. Gavin Newsom Governor of California HON. TANI G. CANTIL- SAKAUYE State Capitol, First Floor Chief Justice of California Chair of the Judicial Council Sacramento, California 95814 HON. MARSHA G. SLOUGH Re: 2020 Language Need and Interpreter Use Study, as required under Chair, Executive and Planning Committee Government Code section 68563 HON. DAVID M. RUBIN Chair, Judicial Branch Budget Committee Chair, Litigation Management Committee Dear Governor Newsom: HON. MARLA O. ANDERSON Attached is the Judicial Council report required under Government Code Chair, Legislation Committee section 68563, which requires the Judicial Council to conduct a study HON. HARRY E. HULL, JR. every five years on language need and interpreter use in the California Chair, Rules Committee trial courts. HON. KYLE S. BRODIE Chair, Technology Committee The study was conducted by the Judicial Council’s Language Access Hon. Richard Bloom Services and covers the period from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2017–18. Hon. C. Todd Bottke Hon. Stacy Boulware Eurie Hon. Ming W. Chin If you have any questions related to this report, please contact Mr. Douglas Hon. Jonathan B. Conklin Hon. Samuel K. Feng Denton, Principal Manager, Language Access Services, at 415-865-7870 or Hon. Brad R. Hill Ms. Rachel W. Hill [email protected]. Hon. Harold W. Hopp Hon. Hannah-Beth Jackson Mr. Patrick M. Kelly Sincerely, Hon. Dalila C. Lyons Ms. Gretchen Nelson Mr. -

RELG 357D1 Sanskrit 2, Fall 2020 Syllabus

RELG 357D1: Sanskrit 2 Fall 2020 McGill University School of Religious Studies Tuesdays & Thursdays, 10:05 – 11:25 am Instructor: Hamsa Stainton Email: [email protected] Office hours: by appointment via phone or Zoom Note: Due to COVID-19, this course will be offered remotely via synchronous Zoom class meetings at the scheduled time. If students have any concerns about accessibility or equity please do not hesitate to contact me directly. Overview This is a Sanskrit reading course in which intermediate Sanskrit students will prepare translations of Sanskrit texts and present them in class. While the course will review Sanskrit grammar when necessary, it presumes students have already completed an introduction to Sanskrit grammar. Readings: All readings will be made available on myCourses. If you ever have any issues accessing the readings, or there are problems with a PDF, please let me know immediately. You may also wish to purchase or borrow a hard copy of Charles Lanman’s A Sanskrit Reader (1884) for ease of reference, but the ebook will be on myCourses. The exact reading on a given day will depend on how far we progressed in the previous class. For the first half of the course, we will be reading selections from the Lanman’s Sanskrit Reader, and in the second half of the course we will read from the Bhagavadgītā. Assessment and grading: Attendance: 20% Class participation based on prepared translations: 20% Test #1: 25% Test #2: 35% For attendance and class participation, students are expected to have prepared translations of the relevant Sanskrit text. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ].