Politics and Urban Development Focus on Jakarta's Shopping Center Trajectory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PT Agung Podomoro Land Tbk

PT Agung Podomoro Land Tbk Public Expose 2 Desember 2019 0 Disclaimer Presentasi ini dipersiapkan semata-mata dan secara eksklusif untuk para pihak terundang untuk tujuan diskusi. Baik presentasi maupun isinya tidak boleh diperbanyak, atau digunakan tanpa izin tertulis dari PT Agung Podomoro Land Tbk. Presentasi ini dapat berisi pernyataan yang menyampaikan harapan berorientasi masa depan yang mewakili pandangan Perusahaan saat ini untuk perkiraan kejadian dan keuangan masa depan. Pandangan tersebut disajikan berdasarkan asumsi saat ini, yang mungkin memiliki berbagai risiko dan potensi perubahan. Disajikan berdasarkan asumsi yang dianggap benar pada saat ini, dan berdasarkan data yang tersedia pada saat presentasi ini dibuat. Perusahaan tidak dapat menjaminan bahwa pandangan tersebut akan, sebagian atau secara keseluruhan, akhirnya terwujud. Hasil yang sebenarnya dapat berbeda secara signifikan dari yang diproyeksikan. 1 Agenda 1. Tentang Perusahaan 2. Kinerja Operasional 3. Kinerja Keuangan 2 PT Agung Podomoro Land Tbk (APLN) Pendapatan Berulang .Malls .Hotels .Lainnya .Pengembang terkemuka dan terdiversifikasi .Pionir pengembangan superblock .Model pengembangan property terintegrasi . IPO di tahun 2010 Penjualan .Pengembangan Superblock .Rumah tapak/apartemen .Lainnya 3 Project Locations 4 Lahan untuk pengembangan* (Hektar) Medan; Balikpapan; 4,9 5,2 Greater Jakarta; Batam; 58,2 40,8 Bandung; 1,8 Karawang ; 5,7 Bogor; 91,2 Dalam Pengembangan Pengembangan; 209 Mendatang; 554 Bali; 7,4 Makassar; 15,0 Jakarta; 36,3 Bandung; 120,5 * Tidak termasuk reklamasi Karawang; 374,9 5 Agenda 1. Tentang Perusahaan 2. Kinerja Operasional 3. Kinerja Keuangan 6 Sekilas 2019 . Penjualan Sofitel senilai Rp 1,6 triliun pada Maret 2019. Pelunasan Obligasi Berkelanjutan I APLN Tahap II Tahun 2014 sebesar Rp750 miliar Juni 2019 . -

Sociocultural Landscape of Rural Community in New Town Development of Bumi Serpong Damai City Kota Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Wahid & Widyawati, 2018 Volume 4 Issue 3, pp.164-180 Date of Publication: 19th November 2018 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2018.43.164180 This paper can be cited as: Wahid, A. G. A. & Widyawati. (2018). Sociocultural Landscape of Rural Community in New Town Development of Bumi Serpong Damai City Kota Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 164-180. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. SOCIOCULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF RURAL COMMUNITY IN NEW TOWN DEVELOPMENT OF BUMI SERPONG DAMAI CITY KOTA TANGERANG SELATAN, INDONESIA Alvin Gus Abdurrahman Wahid Student at Geography Department, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Widyawati Lecturer at Geography Department, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract Bumi Serpong Damai City, a New Town Development in Kecamatan (District) Serpong, Kota Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia, is causing many changes in land usage in its development area and also a flow of immigrants into this area. This phenomenon is causing rural settlement or kampung in this area to change in terms of land usage and population proportions, this kampung, namely Lengkong Ulama, is culturally very rich in traditional religious activities and education. The mentioned changes are affecting the social condition in communal and gathering activities within the kampung and can be explained by its spatial organization across generations. -

PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk Dan Entitas Anakiand Its Subsidiaries

PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk dan Entitas Anakiand its Subsidiaries Laporan Keuangan Konsolidasian/ Consolidated Financial Statements Pada Tanggal 30 September 2019 dan 31 Desember 2018 serta untuk Periode-periode Sembilan Bulan yang Berakhir 30 September 2019 dan 2018/ As of September 30, 2019 and December 31, 2018 and for the Nine-Month Periods Ended September30, 2019 and 2018 PT BUMI SERPONG DAMAI Tbk DAN ENTITAS ANAKJAND ITS SUBSIDIARIES DAFTAR ISIITABLE OF CONTENTS Halaman/ Page Laporan atas Reviu Informasi Keuangan Interim! Report on Review of Interim Financial Information Surat Pernyataan Direksi tentang Tanggung Jawab atas Laporan Keuangan Konsolidasian PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk dan Entitas Anak pada Tanggal 30 September 2019 dan 31 Desember 2018 serta untuk Periode-periode Sembilan Bulan yang Berakhir 30 September 2019 dan 2018/ The Directors' Statement on the Responsibility for Consolidated Financial Statements of PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk and Its Subsidiaries as of September 30, 2019 and December 31, 2018 and for the Nine-Month Periods Ended September 30, 2019 and 2018 LAPORAN KEUANGAN KONSOLIDASIAN — Pada Tanggal 30 September 2019 dan 31 Desember 2018 serta untuk Periode-periode Sembilan Bulan yang Berakhir 30 September 2019 dan 2018/ CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — As of September 30, 2019 and December 31, 2018 and for the Nine-Month Periods Ended September 30, 2019 and 2018 Laporan Posisi Keuangan Konsolidasian/Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 1 Laporan Laba Rugi dan Penghasilan Komprehensif Lain Konsolidasian/Consolidated Statements of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 3 Laporan Perubahan Ekuitas Konsolidasian/Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 4 Laporan Arus Kas Konsolidasian/Conso/idated Statements of Cash Flows 5 Catatan atas Laporan Keuangan Konsolidasian/Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 6 MIRAWATI SENSI IDRIS MOORE STEPHENS Registered Public Accountants Business License No. -

Annual Report 2015

Laporan Tahunan Annual Report. 2015 TABLE OF 1 CONTENTS Daftar Isi 2 VISI DAN MISI PERUSAHAAN 48 JARINGAN BISNIS PERSEROAN Corporate Vision and Mission Our Stores Network 4 SEKILAS ACE 52 RAGAM PRODUK PILIHAN BERKUALITAS Ace at a Glance Quality Selected Products 8 IKHTISAR KEUANGAN 56 ANALISIS DAN PEMBAHASAN MANAJEMEN Financial Highlights Management’s Discussion and Analysis 10 PERISTIWA PENTING TAHUN 2015 60 TANGGUNG JAWAB SOSIAL PERUSAHAAN Significant Events In 2015 Corporate Social Responbility 12 PENGHARGAAN DI TAHUN 2015 64 PENGEMBANGAN SUMBER DAYA MANUSIA Awards in 2015 Human Resources Development 16 SAMBUTAN DEWAN KOMISARIS 70 INFORMASI TENTANG PERUSAHAAN Message from The Board Of Commissioners Corporate Information 19 LAPORAN DIREKSI 72 LAPORAN KEUANGAN AUDITOR 2015 Report from the Board Of Directors Audited Financial Report 2015 22 TATA KELOLA PERUSAHAAN Good Corporate Governance 40 PROFIL PERSEROAN Company Profile Laporan Tahunan Annual Report. 2015 2 Flagship Store Ace Hardware Indonesia VISI DAN MISI Corporate Vision and Mission Laporan Tahunan Annual Report. 2015 3 VISI PERUSAHAAN “Menjadi peritel terdepan di Indonesia untuk produk home improvement dan lifestyle” MISI PERUSAHAAN “Menawarkan ragam produk berkualitas tinggi dengan harga bersaing dan didukung oleh layanan terpadu dari tim profesional” Corporate Vision “We strive to become the leading retail company in Indonesia for home improvement and lifestyle products.” Corporate Mission “We aim to offer a wide range of high-quality products at competitive prices, supported by the integrated service of a professional team.” Laporan Tahunan Annual Report. 2015 4 SEKILAS ACE HARDWARE ACE at a Glance Tahun 1996 menjadi saksi kelahiran gerai Ace Hardware The year of 1996 witnessed the birth of first Ace Hardware pertama di Karawaci, Tangerang, Jawa Barat, melalui PT Ace store in Karawaci, Tangerang, West Java, through PT Ace Hardware Indonesia (AHI) yang didirikan oleh PT Kawan Hardware Indonesia (AHI), which was established by Lama Sejahtera pada tahun 1995. -

Daftar BU BBM Untuk Website Migas.Xlsx

STATUS BADAN USAHA NIAGA MIGAS UNTUK KEGIATAN NIAGA MINYAK BUMI/BBM/HASIL OLAHAN (PERIODE S.D OKTOBER 2020) A. BADAN USAHA NIAGA MIGAS, STATUS: PENGHENTIAN SEMENTARA/PEMBEKUAN No Nama Badan Usaha Alamat Badan Usaha Jenis Kegiatan Usaha 1 PT Hj Nurfadiah Jaya Angkasa Jl. Pulau Samosir no. 27 B Karang Mumus Samarinda Ilir Kalimantan Timur 75113 Niaga Umum BBM B. BADAN USAHA NIAGA MIGAS, STATUS: AKTIF, STATUS PELAPORAN : RUTIN No Nama Badan Usaha Alamat Badan Usaha Jenis Kegiatan Usaha 1 PT Agung Persada Mandiri Jl. Karang Anyar Raya 55 Blok A No.46, Kel. Karang Anyar, Sawah Besar, Jakarta Pusat Niaga Umum BBM 2 PT AKR Corporindo Tbk Wisma AKR Lantai 7 – 8 JL. Panjang Nomor 5 Kebon Jeruk, Jakarta Barat 11530 Niaga Umum BBM 3 PT Andifa Perkasa Energi Perum Jhonlin Indah C no 10 RT 013/003 Gunung Antasari Niaga Umum BBM 4 PT Aneka Petroindo Raya AKR Tower Lantai. 25 Jl. Panjang No. 5 RT. 011 RW 010. Kebon Jeruk, Kebon Jeruk, Jakarta Barat Niaga Umum BBM 5 PT Angkasa Tunggal Selaras Nugrahatama Sentra Arteri Mas Blok I Lt. 4 Jl. Sultan Iskandar Muda No. 10 Niaga Umum Hasil Olahan 6 PT Anigos Jaya Perkasa Jl. Lingkar Utara RT/RW 007/006, Kel. Perwira, Bekasi Utara, Bekasi Niaga Umum BBM 7 PT Anugrah Aldhi Persada Gd Graha BIP Lt 9 Jl Jend Gatot Subroto Kav 23, RT 002/002 Setiabudi, Jakarta Selatan Niaga Umum BBM 8 PT Apex Indopacific Rukan Crown Plaza Blok C-08 Jl. Prof.Dr.Soepomo SH No. 231 Jakarta Selatan Niaga Umum BBM 9 PT Arinda Ananda Arsindo Jl. -

Regional Kabupaten Tipe Outlet Nama Outlet BALI NUSRA KOTA

Regional Kabupaten Tipe Nama Outlet Outlet BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone XIAOMI STORE TEUKU UMAR BALI BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone MEGASTORE RUKO GATOT SUBROTO BALI BALI NUSRA KUPANG Erafone SES LIPPO PLAZA KUPANG BALI NUSRA KUPANG Erafone ERAFONE LIPPO PLAZA KUPANG BALI NUSRA KOTA MATARAM Erafone MEGASTORE RUKO MATARAM LOMBOK BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone SES TRANS STUDIO MALL BALI BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone ERAFONE MALL BALI GALERIA BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone SES BEACHWALK BALI BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone MEGASTORE 2 TEUKU UMAR BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone MEGASTORE RUKO SINGARAJA BALI BALI NUSRA KOTA DENPASAR Erafone TELKOMSEL GRAPARI RENON BALI NUSRA KOTA MATARAM Erafone TELKOMSEL GRAPARI LOMBOK EPICENTRUM MALL BALI NUSRA KOTA MATARAM Erafone ERAFONE LOMBOK EPICENTRUM MALL CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE 2 ITC ROXY MAS JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE 3 ITC ROXY MAS JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE 4 ITC ROXY MAS JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE CENTRAL PARK JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE DAAN MOGOT MALL JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE GREEN SEDAYU MALL JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE MAL CIPUTRA JAKARTA JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE MAL PURI INDAH JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE MAL TAMAN ANGGREK JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE PLAZA SLIPI JAYA JABOTABEK CENTRAL JAKARTA BARAT Erafone ERAFONE PX PAVILION ST MORITS JABOTABEK Internal Regional Kabupaten Tipe -

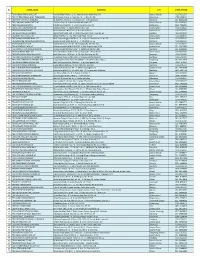

No Nama Alamat1 Alamat2 Propinsi L/A Status Investor Nama

Daftar Pemegang Saham PT Goodyear lndonesia Tbk Per 31 Agustus 2018 No Nama Alamat1 Alamat2 Propinsi L/A Status Investor Nama Pemegang Rekening Jumlah Saham % 1 PT KALIBESAR ASRI Jl Pintu Kecil No.27 Roa Malaka Tambora Jakarta L PERUSAHAAN TERBATAS NPWP PT UOB KAY HIAN SEKURITAS 27.210.000 6,64 2 PT RODA EKAKARYA Jl Pintu Kecil No.27 RT/RW 002/002 Kel.Roa Malaka Kec.Tambora Jakarta L PERUSAHAAN TERBATAS NPWP PT UOB KAY HIAN SEKURITAS 8.300.000 2,02 3 ANTON SIMON JL. AGUNG INDAH M-4 NO.8 RT/RW 015/016 Jakarta L INDIVIDUAL - DOMESTIC PT WATERFRONT SEKURITAS INDONESIA 4.604.400 1,12 4 ANTON SIMON JL AGUNG INDAH M 4 NO 8 RT 015/016, SUNTER AGUNG, TANJUNG PRIOKJakarta L INDIVIDUAL - DOMESTIC NET SEKURITAS, PT 2.748.000 0,67 5 PT. Kalibesar Asri Jl. Pintu Kecil No. 27 Roa Malaka Jakarta L PERUSAHAAN TERBATAS NPWP PT NIKKO SEKURITAS INDONESIA 1.837.400 0,45 6 KENNETH RUDY KAMON 35 LAFAYETTE PLACE A INDIVIDUAL - FOREIGN PT DBS VICKERS SEKURITAS INDONESIA 1.625.000 0,40 7 SSB WLGK S/A GOODHART PARTNERS HORIZON106,ROUTE FUND-2144615378 DE ARLON L-8210 MAMER, LUXEMBOURG Others A INSTITUTION - FOREIGN BUT DEUTSCHE BANK AG 1.343.700 0,33 8 PRIMA TUNAS INVESTAMA, PT. WISMA HAYAM WURUK LT.9 JL. HAYAM WURUK NO. 8 KEBON KELAPAJakarta - GAMBIR L PERUSAHAAN TERBATAS NPWP PT EQUITY SEKURITAS INDONESIA 1.025.000 0,25 9 KENNETH RUDY KAMON 4400 ANDREWS HWY #801, MIDLAND TEXASSUITE - USA 375 306 MIDLAND WEST WALL STREET A INDIVIDUAL - FOREIGN PT. -

H. Winarso Access to Main Roads Or Low Cost Land? Residential Land Developers Behaviour in Indonesia

H. Winarso Access to main roads or low cost land? Residential land developers behaviour in Indonesia In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, On the roadThe social impact of new roads in Southeast Asia 158 (2002), no: 4, Leiden, 653-676 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 02:29:57AM via free access HARYO WINARSO Access to main roads or low cost land? Residential land developers' behaviour in Indonesia The rapid growth of the urban population in the Third World has obvious implications not only for the provision of basic infrastructure but also for land development. It has been reported that in 1990, around 42 per cent of the Third World's total urban population was living in informal settlements, many of them located on urban fringes (World Resource Institute, quoted by Browder, Bohland, and Scarpaci 1995). But many urban residents also live in settlements on urban fringes created by land developers. This is particularly visible in cities of countries that have enjoyed massive economie growth, such as Bangkok (Foo 1992a, 1992b; Dowall 1991). In Jabotabek,1 the private sector has urbanized 16,600 hectares of rural land far away from the built-up area of Jakarta, selling around 25,000 hous- ing units annually. This was achieved by private developers in the Jabotabek area, an emerging mega-urban region in Indonesia, between the 1970s and the 1990s (Winarso 1999; Winarso and Kombaitan 1995). In the Jabotabek area, land developments, particularly those for residential use, have pen- etrated far into rural areas, creating urban sprawl (Henderson, Kuncoro, and Nasution 1996; Firman and Dharmapatni 1994; Firman 1994; Noe 1991; Winarso and Kombaitan 1995). -

No STORE NAME ADDRESS2 CITY STORE PHONE 1 TBS

No STORE_NAME ADDRESS2 CITY STORE_PHONE 1 TBS PONDOK INDAH MALL JKT Pondok Indah Mall Lt. 1 - JL. Metro Pondok Indah Blok IIIB Jakarta Selatan 021-7692353 2 TBS CIPUTRA SERAYA MALL PEKANBARU Mall Ciputra Seraya Lt. Dasar No.18 - Jl. Riau No. 58 Pekanbaru 0761-868618 3 TBS PARIS VAN JAVA BANDUNG RL B20 Paris Van Java - Jl. Sukajadi 137 - 139, Bandung Bandung 022-82063649 4 TBS GANDARIA MAIN STREET JKT Gandaria City - Jl. Sultan Iskandar Muda No. 57 Jakarta Selatan 021-29053091 5 TBS E-WALK BALIKPAPAN E Walk Superblok GF - Jl. Jendral Sudirman No. 71 Balikpapan 0542-7586881 6 TBS KELAPA GADING MALL JKT Kelapa Gading - Jl. Boulevard Raya Kav. 144 Jakarta Utara 021-4533422 7 TBS PLAZA SENAYAN JKT Plaza Senayan 2 ND Floor - JL. Asia Afrika No. 8 Jakarta Pusat 021-5725179 8 TBS GALAXY MALL SURABAYA Galaxy Mall G.101-102 - Jl. Dharmahusada Indah Timur No.14 Surabaya 031-5915032 9 TBS PLUIT MEGA MALL JKT Mega Mall Pluit GF - JL. Pluit Indah Raya No. 36 Jakarta Utara 021-6683878 10 TBS TAMAN ANGGREK MALL JKT Mall Taman Anggrek UG Floor - JL. Letjen S. Parman Kav. 21 No. 78 Jakarta Barat 021-5639296 11 TBS BANDUNG INDAH PLAZA BANDUNG Bandung Indah Plaza GF NO. 5 - Jl. Merdeka No. 56 Bandung 022-4233521 12 TBS BLOK M PLAZA JKT Blok M Plaza UG - 01 - 02 - Jl. Bulungan No. 76 Keb. Baru Jakarta Selatan 021-7209041 13 TBS INDONESIA PLAZA JKT Plaza Indonesia LB# B-08 FLOOR - Jl. MH Thamrin Kav.28-30 Jakarta Pusat 021-29923853 14 TBS TRANS STUDIO MALL BANDUNG Bandung Supermall 1ST Floor - Jl. -

List Store Ibox

List Store iBox NO Store Name Addres 1 IBOX NEW KOTA KASABLANKA JL. Casablanca Raya Kav. 88, Jakarta Selatan, DKI 2 IBOX CILANDAK TOWN SQUARE Cilandak Town Square Ground Floor #065, Jl. T.B. 3 IBOX GANDARIA CITY Gandaria City 1st Floor #189, Jl. KH. M. Syafi'i Hadzami 4 IBOX KEMANG Lippo Mall Kemang 2nd Floor L2-27, Jl. Pangeran 5 IBOX PEJATEN VILLAGE Pejaten Village Lt. L2 – 08-09 Jl. Warung Jati Barat No. 6 IBOX RATU PLAZA 2 Ratu Plaza 1st Floor #8, Jl. Jendral Sudirman No. 9 7 IBOX MALL OF AMBASSADOR II Mal Ambasador 3rd Floor #18, Jl. Prof. Dr. Satrio Kav. FIRST FLOOR, UNIT NO. FL1 - 22 MARGO CITY, JL. 8 IBOX MARGO CITY MARGONDA RAYA NO. 358, DEPOK 16423 Ground Floor / 01 Jl. Juanda No. 99 Bakti Jaya Sukma 9 IBOX PESONA SQUARE DEPOK Jaya, Kota Depok, Jawa Barat 16418 10 IBOX FLAGSHIP SENAYAN CITY Senayan City 4th Floor #4-29 Jl. Asia Afrika Lot 19 Kode IBOX FLAGSHIP SUMMARECON Jl. Boulevard raya Gading Serpong Pakulonan Barat 11 MALL SERPONG Kelapa Dua Unit #GF211-212-215 IBOX BAYWALK MALL (GREEN Bay Walk Mall 4th Floor #36 Green Bay Pluit Jl. Pluit 12 BAY PLUIT) Karang Ayu, Penjaringan, Jakarta Utara 14450 Unit GF A3 001,002,016,017 Jl. Boulevard Artha Gading 13 IBOX MAL ARTHA GADING No.1, RT.18/RW.8, Klp. Gading Bar., Kec. Klp. Gading, Kota Jkt Utara, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 14240 Mall of Indonesia Ground Floor #GF–A5 Jl. Raya 14 IBOX MALL OF INDONESIA NEW Boulevard Barat, Kelapa Gading, Jakarta Utara 14240 Jl. -

Admedika National Provider Network Jabodetabek & Banten : Jakarta Bogor Depok Tanggerang Bekasi Banten

AdMedika National Provider Network Jabodetabek & Banten : Jakarta Bogor Depok Tanggerang Bekasi Banten Updated : February 2018 Provinsi Kab / Kota Provider Alamat Tel Number Fax Number BANTEN TANGERANG MEDIPRO CLINIC PASAR KEMIS PERUM WISMA MAS, BLOK A1, NO.30-31, PASAR KEMIS, KUTA JAYA 021-59318964| 021-59318965 BANTEN TANGERANG DENTAL PREMIER BINTARO ( D/H DENTAL JL. MH THAMRIN NO.1, SEKTOR 7, BINTARO JAYA 021-745 5500; 021-27625500 021-748 64854/745 58 INTERNASIONAL ext 1680|- BANTEN TANGERANG RSIA. BUAH HATI PAMULANG JL. RAYA SILIWANGI NO 189 PONDOK BENDA PAMULANG 021-7421149 / 7414488| 021-7420322 BANTEN TANGERANG RS. OMNI ALAM SUTERA JL. ALAM SUTERA BOULEVARD KAV.25 SERPONG 021-29779999/85550711 - 021-5312 8666 353438|0711 - 353438 BANTEN TANGERANG LAB. PRODIA BUMI SERPONG DAMAI (BSD) JL. LETNAN SUTOPO, RUKO GOLDEN MADRID BLOK B NO.1-2, BUMI 021-53160403/4| 021-53160406 SERPONG DAMAI BANTEN TANGERANG RSIA. CITRA ANANDA JL. RE MARTADINATA NO. 30, CIPUTAT (021) 7401347/ 0852 1795 (021) 7491701 1795| BANTEN TANGERANG RS ARIA SENTRA MEDIKA JL. ARIA PUTRA NO. 9 KEDAUNG PAMULANG, TANGERANG SELATAN 021-7499199/ 7401376| 021-7495864/7400956 15431 BANTEN TANGERANG KLINIK SATELIT GSO CENGKARENG AREA PERKANTORAN GARUDA SENTRA OPERASI (GSO) GEDUNG 021-25601565| 021-5501801 POLIKLINIK GSM BANDARA SOEKARNO-HATTA CENGKARENG BANTEN TANGERANG KLINIK & LAB BETH RAPHA AGAVE INSANI JL. MAULANA HASANUDIN Gg.AMPERA II NO.7-8, PORIS GAGA, BATU 021-5445855 / 68800855| 021-5445855 CEPER BANTEN TANGERANG KLINIK & APOTEK KF 447 CIRENDEU JL. CIRENDEU RAYA NO.27C CIPUTAT 021-7415997| -021-7415997 BANTEN TANGERANG KLINIK PESONA LEGOK JL. RAYA LEGOK KM 7 DESA CIJANTRA KEC. -

Indonesia- Jakarta- Landed Residential Q4 2019

M A R K E T B E AT GREATER JAKARTA Landed Residential H2 2019 YoY 12-Mo. DEMAND: Healthy Growth after the Challenging Semester Chg Forecast The overall Greater Jakarta landed residential market started to see a healthy growth in the second semester of 2019. Recovering from the challenging first semester due to the tight political atmosphere, the demand showed a positive trend. The average number of housing units 4.42% transacted increased to 28.9 units per month per estate, rising by about 6.6 units from previous semester’s average. The average monthly take-up Price Growth YoY value also improved to approximately IDR 43.1 billion per estate, with the total take-up value rising by 32.7% from the previous semester. 94.54% Tangerang continued to be the most active submarket for landed residential market in Greater Jakarta area in terms of both supply and demand. Sales Rate H2 2019 The area has an average monthly take-up of 41.5 units per month per estate, a significant increase of 13.7 units per estate from the previous semester’s figure. The average transaction value in this area reached IDR 72.4 billion per month per estate. 3,826 New Launched H2 2019 In the overall Greater Jakarta market, the middle segment houses remained to contribute to the highest proportion of housing transactions in the second half of 2019, even increased in share to 45.8%. In this segment, the most coveted units were priced at IDR 1.1 to 1.7 billion with building Source: Cushman & Wakefield Indonesia Research size ranging from 52 to 77 square meters (sq.m.) and land size between 55 to 90 square meters (sq.m.).