Paradigm Shift: a Challenge to Naturalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

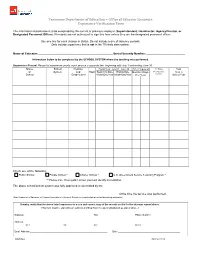

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate. -

Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/10/2011, SPi 3 Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts Johannes Roessler On one view, an adequate account of causal understanding may focus exclusively on what is involved in mastering general causal concepts (concepts such as ‘x causes y’ or ‘p causally explains q’). An alternative view is that causal understanding is, partly but irreducibly, a matter of grasping what Anscombe called special causal concepts, con- cepts such as ‘push’, ‘flatten’,or‘knock over’. We can label these views generalist vs particularist approaches to causal understanding. It is worth emphasizing that the contrast here is not between two kinds of theories of the metaphysics of causation, but two views of the nature and perhaps source of ordinary causal understanding. One aim of this paper is to argue that it would be a mistake to dismiss particularism because of its putative metaphysical commitments. I begin by formulating an intuitively attractive version of particularism due to P.F. Strawson, a central element of which is what I will call na¨ıve realism concerning mechanical transactions. I will then present the account with two challenges. Both challenges reflect the worry that Strawson’s particularism may be unable to acknowledge the intimate connection between causa- tion and counterfactuals, as articulated by the interventionist approach to causation. My project will be to allay these concerns, or at least to explore how this might be done. My (tentative) conclusion will be that Strawson’sna¨ıve realism can accept what interventionism has to say about ordinary causal understanding, and that intervention- ism should not be seen as being committed to generalism. -

A Defense of Ethical Relativism One Entry in a Long Series of Possible Adjustments

A Defense of Ethical Relativism one entry in a long series of possible adjustments. These adjustments, whether they are in mannerisms like the ways of showing RUTH BENEDICT anger, or joy, or grief in any society, or in major human drives like those of sex, prove to be far more variable than experience in any one culture would suggest. In From Benedict, Ruth "Anthropology and the Abnormal," Journal of General Psychology, 10, 1934. certain fields, such as that of religion or of formal marriage arrangements, these wide limits of variability are well known and can be fairly described. In others it is Ruth Benedict (1887-1948), a foremost American anthropologist, taught at not yet possible to give a generalized account, but that does not absolve us of the Columbia University, and she is best known for her book Pattern of Culture task of indicating the significance of the work that has been done and of die (1935). Benedict views social systems as communities with common beliefs problems that have arisen. and practices, which have become integrated patterns of ideas and practices. One of these problems relates to the customary modern normal-abnormal Like a work of art, a culture chooses which theme from its repertoire of categories and our conclusions regarding them. In how far are such categories basic tendencies to emphasize and then produces a grand design, favoring culturally determined, or in how far can we with assurance regard them as absolute? those tendencies. The final systems differ from one another in striking ways, In how far can we regard inability to function socially as abnormality, or in how far but we have no reason to say that one system is better than another. -

What Is Meant by “Christian Dualism” (Genuine Separation

Jeremy Shepherd October 15, 2004 The Friday Symposium Dallas Baptist University “Christian Enemy #1: Dualism Exposed & Destroyed” “The Fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge, but fools despise wisdom and discipline.” - Proverbs 1:7 “Christianity is not a realm of life; it’s a way of life for every realm”1 Introduction When I came to Dallas Baptist University I had a rather violent reaction to what I thought was a profound category mistake. Coming from the public school system, I had a deeply embedded idea of how “religious” claims ought to relate, or should I say, ought not to relate, with “worldly affairs.” To use a phrase that Os Guinness frequently uses, I thought that “religion might be privately engaging but publicly irrelevant.”2 I was astonished at the unashamed integration of all these “religious” beliefs into other realms of life, even though I myself was a Christian. The key word for me was: unashamed. I thought to myself, “How could these people be so shameless in their biases?” My reaction to this Wholistic vision of life was so serious that I almost left the university to go get myself a “real” education, one where my schooling wouldn’t be polluted by all of these messy assumptions and presuppositions, even if they were Christian. My worldview lenses saw “education” as something totally separate from my “faith.” I was a model student of the American public school system, and like most other students, whether Christian or not, the separation of “church/state” and “faith/education” was only a small part of something much deeper and much more profound, the separation of my “faith” from the rest of my “life.” Our public schools are indoctrinating other students who have this same split-vision3, in which “faith” is a private thing, which is not to be integrated into the classroom. -

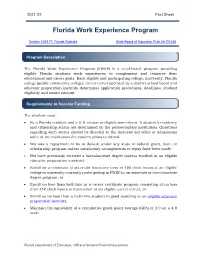

Florida Work Experience Program

2021-22 Fact Sheet Florida Work Experience Program Section 1009.77, Florida Statutes State Board of Education Rule 6A-20.038 Program Description The Florida Work Experience Program (FWEP) is a need-based program providing eligible Florida students work experiences to complement and reinforce their educational and career goals. Each eligible and participating college, university, Florida college (public community college), career center operated by a district school board and educator preparation institute determines application procedures, deadlines, student eligibility and award amount. Requirements to Receive Funding The student must: • Be a Florida resident and a U.S. citizen or eligible non-citizen. A student’s residency and citizenship status are determined by the postsecondary institution. Questions regarding such status should be directed to the financial aid office or admissions office of the institution the student plans to attend. • Not owe a repayment or be in default under any state or federal grant, loan, or scholarship program unless satisfactory arrangements to repay have been made. • Not have previously received a baccalaureate degree (unless enrolled in an eligible educator preparation institute). • Enroll for a minimum of six credit hours per term or 180 clock hours at an eligible college or university currently participating in FWEP in an associate or baccalaureate degree program, or • Enroll no less than half-time in a career certificate program consisting of no less than 450 clock hours of instruction at an eligible career center, or • Enroll as no less than a half-time student in good standing at an eligible educator preparation institute. • Maintain the equivalent of a cumulative grade point average (GPA) of 2.0 on a 4.0 scale. -

On the Mind/Body Problem: the Theory of Essence

On the Mind/Body Problem: The Theory of Essence J. Kenneth Arnette, Ph.D. Colorado State University ABSTRACT: The classical mind/body problem can be approached empiri cally, using instances of the near-death experience (NDE) as experimental data. The monistic viewpoint, that the mind is the functioning of the brain, finds little support in the NDE data, while dualism, mind and body as separate entities, is consistent with NDE research to date. Comparison of the details of the NDE with predictions from theoretical cosmology shows strong similarities between the two and further strengthens the case for dualism. A theory of human nature is proposed that incorporates these similarities. The mind/body problem has been a topic of great interest to philoso phers, scientists, and psychologists throughout history. From the spec ulations of Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek philosophers to the dualist viewpoint of Descartes to modern psychology's material monist bent, the mind/body relationship has helped form the foundations of para digms related to the understanding of human nature. There are two fundamental positions one might reasonably take on the physical relationship between mind and body. I will call these the monist and dualist positions. The monist position is stated most eco nomically as: the mind is nothing more than the biological functioning of the brain. Consider an analogy with computers. The monist might say that the brain corresponds to the central processing unit (CPU) of the computer, while the body and its organ systems are analogous to the peripherals in a computer system. The CPU serves to supervise J. -

Immanuel Kant's Theory of Knowledge: Exploring the Relation Between

Immanuel Kant’s Theory of Knowledge: Exploring the Relation between Sensibility and Understanding Wendell Allan Marinay Kant’s critique of reason does not provide an ultimate justification of knowledge, is not the last word in philosophy but is an initial thesis aimed at successfully solving the challenge posed by two warring schools of thought during Kant’s time: empiricism and rationalism.1 Following the ancient-Greek’s nothing-in-the-mind-without-passing-through-the- senses (Aristotle), Immanuel Kant’s inquiry of knowledge starts with the things “seen” or “experienced.”2 Such inquiry entails the materials and a process by which there can (probably) be known. It probes into or upon the constitution of human reason – an epistemic investigation from within yet necessarily involving from without. This is so because “in the mind we have the pure forms of sensible intuition and the pure concepts of an object in general. Extraneous to the mind we have the unknown and unknowable source of the matter for these forms, the source of that out of which our contentful experience is made.”3 Kant mentions two faculties of the mind that are involved in the knowing process, namely, sensibility and understanding. “He distinguishes between the receptive faculty of sensibility, through which we have intuitions, and the active faculty of understanding, which is the source of concepts.”4 Through the former, the objects are “given” while 1 Otfried Höffe. Immanuel Kant trans. Marshall Farrier (New York: State University of New York Press, 1994), 55. 2 We should not be misled that by starting with things seen or experienced, knowledge would mean like a result of or is consequent to such experience. -

What Psychodynamic Psychotherapists Think About Free Will and Determinism and How That Impacts Their Clinical Practice : a Qualitative Study

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2012 What psychodynamic psychotherapists think about free will and determinism and how that impacts their clinical practice : a qualitative study Patrick J. Cody Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cody, Patrick J., "What psychodynamic psychotherapists think about free will and determinism and how that impacts their clinical practice : a qualitative study" (2012). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/872 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patrick Cody What Psychodynamic Psychotherapists Think about Free Will and Determinism and How that Impacts their Clinical Practice: A Qualitative Study ABSTRACT This qualitative study explored psychodynamic psychotherapists’ beliefs about free will and determinism and how these impact their work with clients. A secondary goal was to determine if and how knowledge of psychodynamic theory, neuropsychology and/or physics has shaped those views. Twelve clinicians were asked questions related to free will, determinism and clients’ behavioral change. All participants said that psychodynamic theory has influenced their beliefs, and a majority said that neuropsychology has done so. Major findings include that 11 of the 12 participants endorsed the concept of compatibilism, that free will and determinism can co- exist and are not mutually exclusive in impacting behavior. This finding compares to, but does not confirm, research that found psychodynamic clinicians were more deterministic than other clinicians (McGovern, 1986), and it contrasts with research that suggests that the science related to free will and determinism has not reached the field and influenced clinical practice (Wilks, 2003).