On the Mind/Body Problem: the Theory of Essence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 4-16-2012 Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Krista, Hyde Dawn, "Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife" (2012). Theses. 261. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Krista Hyde M.L.A., Washington University in St. Louis, 2010 B.A., Philosophy, Southeast Missouri State University – Cape Girardeau, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Philosophy April 2012 Advisory Committee Gualtiero Piccinini, Ph.D. Chair Jon McGinnis, Ph.D. John Brunero, Ph.D. Copyright, Krista Hyde, 2012 Abstract Thomas Aquinas nearly succeeds in addressing the persistent problem of the mind-body relationship by redefining the human being as a body-soul (matter-form) composite. This redefinition makes the interaction problem of substance dualism inapplicable, because there is no soul “in” a body. However, he works around the mind- body problem only by sacrificing an immaterial afterlife, as well as the identity and separability of the soul after death. Additionally, Thomistic psychology has difficulty accounting for the transmission of universals, nor does it seem able to overcome the arguments for causal closure. -

Comparativeurban Studies Project

COMPARATIVE URBAN STUDIES PROJECT URBAN UPDATE September 2007 NO. 12 Cities and Fundamentalisms WRITTEN BY: Nezar AlSayyad, Professor of Architecture, Planning, and Urban History & Chair of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California at Berkeley; Mejgan Massoumi, Program Assistant, Comparative Urban Studies Project (2005-2007); Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Assistant Professor, Draper Faculty Fellow (The City), New York University. With the unanticipated resur- gence of religious and ethnic loy- alties across the world, commu- nities are returning to, reinvigo- rating, and giving new meaning to religions and their common practices. Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism, among others, are experiencing new in- fl uxes of commitments and tra- ditions. These changes have been coupled with the breakdown of order and of state power under the neo-liberal economic para- Top Row, Left to Right: Salwa Ismail, Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Raka Ray, Blair Ruble, Renu Desai, Nezar AlSayyad. Bottom Row, Left to Right: digm of civil society which have Omri Elisha, Emily Gottreich, Mona Harb, Mejgan Massoumi. created vacuums in the provi- sion of social services. Religious groups in many countries around the world are increasingly providing those services left unattended to by state bureaucracies. The once sacred divide between church and COMPARATIVE URBAN STUDIES PROJECT state or the confi nement of religion to the pri- fundamentalisms in several parts of the world. The vate sphere is now being vigorously challenged systematic transformation of the urban landscape as radical religious groups not only gain ground through various strategies of religious funda- within sovereign nation-states but in fact forge mentalism has led to the redefi nition of minority enduring and powerful transnational connections space in many cities. -

Conceptual Analysis and the Essence of Space: Kant's Metaphysical

AGPh 2015; 97(4): 416–457 James Messina* Conceptual Analysis and the Essence of Space: Kant’s Metaphysical Exposition Revisited DOI 10.1515/agph-2015-0017 Abstract: I offer here an account of the methodology, historical context, and content of Kant’s so-called “Metaphysical Exposition of the Concept of Space” (MECS). Drawing on Critical and pre-Critical texts, I first argue that the arguments making up the MECS rest on a kind of conceptual analysis, one that yields (analytic) knowledge of the essence of space. Next, I situate Kant’s MECS in what I take to be its proper historical context: the debate between the Wolffians and Crusius about the correct analysis of the concept of space. Finally, I draw on the results of previous sections to provide a reconstruction of Kant’s so-called “first apriority argument.” On my reconstruction, the key premise of the argument is a claim to the effect that space grounds the possibility of the co-existence of whatever things occupy it. “To investigate the essences of things is the busi- ness and the end of philosophy.” (AA 24:115) 1 Introduction In the Transcendental Aesthetic of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant argues that space is the a priori form of outer intuition (call this the Form Thesis).¹,² Kant’s 1 References to the Critique of Pure Reason are given according to the pagination of the first (A) and second (B) editions. In quotations I have followed Critique of Pure Reason (Kant 1998). References to other works by Kant are given by volume and page number of the Berlin Akademie edition (cited as AA). -

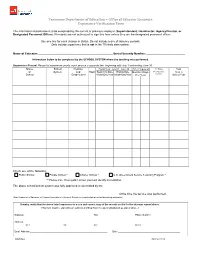

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Can God's Goodness Save the Divine Command Theory

CAN GOD’S GOODNESS SAVE THE DIVINE COMMAND THEORY FROM EUTHYPHRO? JEREMY KOONS Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar Abstract. Recent defenders of the divine command theory like Adams and Alston have confronted the Euthyphro dilemma by arguing that although God’s commands make right actions right, God is morally perfect and hence would never issue unjust or immoral commandments. On their view, God’s nature is the standard of moral goodness, and God’s commands are the source of all obligation. I argue that this view of divine goodness fails because it strips God’s nature of any features that would make His goodness intelligible. An adequate solution to the Euthyphro dilemma may require that God be constrained by a standard of goodness that is external to Himself – itself a problematic proposal for many theists. The Euthyphro dilemma is often thought to present a fatal problem for the divine command theory (aka theological voluntarism). Are right acts commanded by God because they are right, or are they right because they are commanded by God? If the former, then there is a standard of right and wrong independent of God’s commands; God’s commands are not relevant in determining the content of morality. This option seems to compromise God’s sovereignty in an important way. But the second horn of the dilemma presents seemingly insurmountable problems, as well. First, if God’s commands make right actions right, and there is no standard of morality independent of God’s commands, then that seems to make morality arbitrary. Thus, murder is not wrong because it harms someone unjustly, but merely because God forbids it; there is (it seems) no good connection between reason and the wrongness of murder. -

Existentialism

TOPIC FOR- SEM- III ( PHIL-CC 10) CONTEMPORARY WESTERN PHILOSOPHY BY- DR. VIJETA SINGH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY PATNA UNIVERSITY Existentialism Existentialism is a philosophy that emphasizes individual existence, freedom and choice. It is the view that humans define their own meaning in life, and try to make rational decisions despite existing in an irrational universe. This philosophical theory propounds that people are free agents who have control over their choices and actions. Existentialists believe that society should not restrict an individual's life or actions and that these restrictions inhibit free will and the development of that person's potential. History 1 Existentialism originated with the 19th Century philosopher Soren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, but they did not use the term (existentialism) in their work. In the 1940s and 1950s, French existentialists such as Jean- Paul Sartre , Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir wrote scholarly and fictional works that popularized existential themes, such as dread, boredom, alienation, the absurd, freedom, commitment and nothingness. The first existentialist philosopher who adopted the term as a self-description was Sartre. Existentialism as a distinct philosophical and literary movement belongs to the 19th and 20th centuries, but elements of existentialism can be found in the thought (and life) of Socrates, in the Bible, and in the work of many pre-modern philosophers and writers. Noted Existentialists: Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) Nationality Denmark Friedrich Nietzsche(1844-1900) Nationality Germany Paul Tillich(1886-1965) Nati…United States, Germany Martin Heidegger ( 1889-1976) Nati…Germany Simone de Beauvior(1908-1986) Nati…France Albert Camus (1913-1960) Nati….France Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1980) Nati….France 2 What does it mean to exist ? To have reason. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate. -

Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/10/2011, SPi 3 Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts Johannes Roessler On one view, an adequate account of causal understanding may focus exclusively on what is involved in mastering general causal concepts (concepts such as ‘x causes y’ or ‘p causally explains q’). An alternative view is that causal understanding is, partly but irreducibly, a matter of grasping what Anscombe called special causal concepts, con- cepts such as ‘push’, ‘flatten’,or‘knock over’. We can label these views generalist vs particularist approaches to causal understanding. It is worth emphasizing that the contrast here is not between two kinds of theories of the metaphysics of causation, but two views of the nature and perhaps source of ordinary causal understanding. One aim of this paper is to argue that it would be a mistake to dismiss particularism because of its putative metaphysical commitments. I begin by formulating an intuitively attractive version of particularism due to P.F. Strawson, a central element of which is what I will call na¨ıve realism concerning mechanical transactions. I will then present the account with two challenges. Both challenges reflect the worry that Strawson’s particularism may be unable to acknowledge the intimate connection between causa- tion and counterfactuals, as articulated by the interventionist approach to causation. My project will be to allay these concerns, or at least to explore how this might be done. My (tentative) conclusion will be that Strawson’sna¨ıve realism can accept what interventionism has to say about ordinary causal understanding, and that intervention- ism should not be seen as being committed to generalism. -

A Defense of Ethical Relativism One Entry in a Long Series of Possible Adjustments

A Defense of Ethical Relativism one entry in a long series of possible adjustments. These adjustments, whether they are in mannerisms like the ways of showing RUTH BENEDICT anger, or joy, or grief in any society, or in major human drives like those of sex, prove to be far more variable than experience in any one culture would suggest. In From Benedict, Ruth "Anthropology and the Abnormal," Journal of General Psychology, 10, 1934. certain fields, such as that of religion or of formal marriage arrangements, these wide limits of variability are well known and can be fairly described. In others it is Ruth Benedict (1887-1948), a foremost American anthropologist, taught at not yet possible to give a generalized account, but that does not absolve us of the Columbia University, and she is best known for her book Pattern of Culture task of indicating the significance of the work that has been done and of die (1935). Benedict views social systems as communities with common beliefs problems that have arisen. and practices, which have become integrated patterns of ideas and practices. One of these problems relates to the customary modern normal-abnormal Like a work of art, a culture chooses which theme from its repertoire of categories and our conclusions regarding them. In how far are such categories basic tendencies to emphasize and then produces a grand design, favoring culturally determined, or in how far can we with assurance regard them as absolute? those tendencies. The final systems differ from one another in striking ways, In how far can we regard inability to function socially as abnormality, or in how far but we have no reason to say that one system is better than another.