Immanuel Kant's Theory of Knowledge: Exploring the Relation Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polarization of Reality †

AEA Papers and Proceedings 2020, 110: 324–328 https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20201072 The Polarization of Reality † By Alberto Alesina, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva* Evidence is growing that Americans are voters have been illustrated in the political sci- polarized not only in their views on policy issues ence literature. Bartels 2002 shows that party and attitudes toward government and society identification shapes (perception) of economic but also in their perceptions of the same factual indicators that can be seen as the government’s reality. In this paper, we conceptualize how to “performance indicators” e.g., unemployment think about the polarization of reality and review or inflation , with Republicans( being more opti- recent papers that show that Republicans and mistic than) Democrats on economic variables Democrats as well as Trump and non-Trump during the Reagan presidency.1 Similar results voters since (2016 view the same reality through about the importance of partisan assessment a different lens. Perhaps) as a result, they hold of the government’s performance in shaping different views about policies and what should perceptions of economic indicators is found in be done to address different economic and social Conover, Feldman, and Knight 1987 . More issues. recently, Jerit and Barabas 2012( shows) that The direction of causality is unclear. On the people perceive the same reality( in a) way consis- one hand, individuals could select into political tent with their political views and that learning affiliations on the basis of their perceptions of is selective: partisans have higher knowledge reality. On the other hand, political affiliation for facts that corroborate their world views and affects the information one receives, the groups lower knowledge of facts that challenge them. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Immanuel Kant Was Born in 1724, and Published “Religion Within The

CHAPTER FIVE THE PHENOMENOLOGY AND ‘FORMATIONS OF CONSCIOUSNESS’ It is this self-construing method alone which enables philosophy to be an objective, demonstrated science. (Hegel 1812) Immanuel Kant was born in 1724, and published “Religion within the limits of Reason” at the age of 70, at about the same time as the young Hegel was writing his speculations on building a folk religion at the seminary in Tübingen and Robespierre was engaged in his ultimately fatal practical experiment in a religion of Reason. Kant was a huge figure. Hegel and all his young philosopher friends were Kantians. But Kant’s system posed as many problems as it solved; to be a Kantian at that time was to be a participant in the project which Kant had initiated, the development of a philosophical system to fulfill the aims of the Enlightenment; and that generally meant critique of Kant. We need to look at just a couple of aspects of Kant’s philosophy which will help us understand Hegel’s approach. “I freely admit,” said Kant , “it was David Hume ’s remark [that Reason could not prove necessity or causality in Nature] that first, many years ago, interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave a completely differ- ent direction to my enquiries in the field of speculative philosophy” (Kant 1997). Hume’s “Treatise on Human Nature” had been published while Kant was still very young, continuing a line of empiricists and their rationalist critics, whose concern was how knowledge and ideas originate from sensation. Hume was a skeptic; he demonstrated that causality could not be deduced from experience. -

Dilemmas of Objectivity

SOCIALEPISTEMOLOGY , 2002, VOL. 16, NO . 3, 267–281 Dilemmas of objectivity MARIANNE JANACK Objectivityis a virtuein most circles.As weevaluateour students (even those we don’t like)we tryto be objective. As wedeliberateon juries,we tryto be objective about the accused and thevictim, the prosecutor and thedefence. As wetoteup theevidence for and againsta certainposition or theory, we try to separate our personal preferences fromthe argument, or we try to separate the arguer (and ourevaluation of him/ her) fromthe case presented.Sometimes we do wellat this,sometimes we do lesswell at it,but we recognize something valuable intheeffort. Considerthe following cases inwhich objectivity or its failure is at issue: (1)A professorgives his favourite student an Ainaclass inwhichthe student has done onlymediocre work. (2)A scientistoverlooks evidence that would call intoquestion a theorythat she has goneout on alimbto defend,and has investedmuch timeand energyin pursuing. (3)A scientistskews data inorder to bolster support for a favouritepolitical cause. (4)A particularphilosophy journal, which does not use a blindreview process, only publishesarticles written by men. (5)A memberof a trialjury questions evidence presented in atrialbecause it conicts withracist stereotypes. Some ofthese invocations of objectivity imply that a separationshould exist between thesource or origin of the theory or argument and theargument itself. Some imply thatour deliberations should be answerable only to ‘ theevidence’ or ‘ thefacts’ and notsimply to our own preferences and idiosyncrasies.Some implythat our emotionsor biases (broadly understood to include emotions) should not interfere withour reasoning. Inits ontological guise, the appeal toobjectivity is a wayof appealing to the way thingsare, or to the world as itis independently of our desires about howwe want it tobe. -

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(S): Cleo H

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(s): Cleo H. Cherryholmes Source: Educational Researcher, Vol. 21, No. 6, (Aug. - Sep., 1992), pp. 13-17 Published by: American Educational Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1176502 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aera. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Notes on Pragmatismand Scientific Realism CLEOH. CHERRYHOLMES Ernest R. House's article "Realism in plicit declarationof pragmatism. Here is his 1905 statement ProfessorResearch" (1991) is informative for the overview it of it: of scientificrealism. -

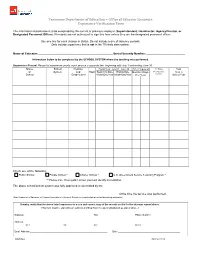

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

5. What Matters Is the Motive / Immanuel Kant

This excerpt is from Michael J. Sandel, Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do?, pp. 103-116, by permission of the publisher. 5. WHAT MATTERS IS THE MOTIVE / IMMANUEL KANT If you believe in universal human rights, you are probably not a utili- tarian. If all human beings are worthy of respect, regardless of who they are or where they live, then it’s wrong to treat them as mere in- struments of the collective happiness. (Recall the story of the mal- nourished child languishing in the cellar for the sake of the “city of happiness.”) You might defend human rights on the grounds that respecting them will maximize utility in the long run. In that case, however, your reason for respecting rights is not to respect the person who holds them but to make things better for everyone. It is one thing to con- demn the scenario of the su! ering child because it reduces overall util- ity, and something else to condemn it as an intrinsic moral wrong, an injustice to the child. If rights don’t rest on utility, what is their moral basis? Libertarians o! er a possible answer: Persons should not be used merely as means to the welfare of others, because doing so violates the fundamental right of self-ownership. My life, labor, and person belong to me and me alone. They are not at the disposal of the society as a whole. As we have seen, however, the idea of self-ownership, consistently applied, has implications that only an ardent libertarian can love—an unfettered market without a safety net for those who fall behind; a 104 JUSTICE minimal state that rules out most mea sures to ease inequality and pro- mote the common good; and a celebration of consent so complete that it permits self-in" icted a! ronts to human dignity such as consensual cannibalism or selling oneself into slav ery. -

INTUITION .THE PHILOSOPHY of HENRI BERGSON By

THE RHYTHM OF PHILOSOPHY: INTUITION ·ANI? PHILOSO~IDC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON By CAROLE TABOR FlSHER Bachelor Of Arts Taylor University Upland, Indiana .. 1983 Submitted ~o the Faculty of the Graduate College of the · Oklahoma State University in partial fulfi11ment of the requirements for . the Degree of . Master of Arts May, 1990 Oklahoma State. Univ. Library THE RHY1HM OF PlllLOSOPHY: INTUITION ' AND PfnLoSOPlllC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON Thesis Approved: vt4;;. e ·~lu .. ·~ests AdVIsor /l4.t--OZ. ·~ ,£__ '', 13~6350' ii · ,. PREFACE The writing of this thesis has bee~ a tiring, enjoyable, :Qustrating and challenging experience. M.,Bergson has introduced me to ·a whole new way of doing . philosophy which has put vitality into the process. I have caught a Bergson bug. His vision of a collaboration of philosophers using his intuitional m~thod to correct, each others' work and patiently compile a body of philosophic know: ledge is inspiring. I hope I have done him justice in my description of that vision. If I have succeeded and that vision catches your imagination I hope you Will make the effort to apply it. Please let me know of your effort, your successes and your failures. With the current challenges to rationalist epistemology, I believe the time has come to give Bergson's method a try. My discovery of Bergson is. the culmination of a development of my thought, one that started long before I began my work at Oklahoma State. However, there are some people there who deserv~. special thanks for awakening me from my ' "''' analytic slumber. -

Logical Empiricism / Positivism Some Empiricist Slogans

4/13/16 Logical empiricism / positivism Some empiricist slogans o Hume’s 18th century book-burning passage Key elements of a logical positivist /empiricist conception of science o Comte’s mid-19th century rejection of n Motivations for post WW1 ‘scientific philosophy’ ‘speculation after first & final causes o viscerally opposed to speculation / mere metaphysics / idealism o Duhem’s late 19th/early 20th century slogan: o a normative demarcation project: to show why science ‘save the phenomena’ is and should be epistemically authoritative n Empiricist commitments o Hempel’s injunction against ‘detours n Logicism through the realm of unobservables’ Conflicts & Memories: The First World War Vienna Circle Maria Marchant o Debussy: Berceuse héroique, Élégie So - what was the motivation for this “revolutionary, written war-time Paris (1914), heralds the ominous bugle call of war uncompromising empricism”? (Godfrey Smith, Ch. 2) o Rachmaninov: Études-Tableaux Op. 39, No 8, 5 “some of the most impassioned, fervent work the composer wrote” Why the “massive intellectual housecleaning”? (Godfrey Smith) o Ireland: Rhapsody, London Nights, London Pieces a “turbulant, virtuosic work… Consider the context: World War I / the interwar period o Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 written just before he fled as a fugitive himself to the US (1917); military aggression & sardonic irony o Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin each of six movements dedicated to a friend who died in the war x Key problem (1): logicism o Are there, in fact, “rules” governing inference -

Feminist Empiricism Draws in Various Ways

2 FEMINIST EMPIRICISM CATHERINE E. HUNDLEBY eminist empiricism draws in various ways developing new accounts of agency in knowl- on the philosophical tradition of empiri- edge emerges as the second theme in feminist F cism, which can be defined as epistemol- empiricism. ogy that gives primary importance to knowledge Most feminist empiricists employ the meth- based on experience. Feminist demands for atten- odology for developing epistemology known as tion to women’s experiences suggest that empiri- naturalized or naturalist epistemology. Naturalism cism can be a promising resource for developing is controversial, but it welcomes disputation, a feminist account of knowledge. Yet feminists takes up new resources for epistemology on an also value empiricism’s purchase on science and ongoing basis, and encourages multiple approaches the empiricist view that knowers’ abilities depend to the evaluation of knowledge. This pluralism on their experiences and their experiential histo- undercuts naturalism’s and empiricism’s conser- ries, including socialization and psychological vative tendencies and imbues current formula- development. tions of empiricism with radical potential. This chapter explores the attractions of empiricism for feminists. Feminist empiricist analysis ranges from broad considerations about FEMINIST ATTRACTION TO EMPIRICISM popular understandings to technical analysis of narrowly defined scientific fields. Whatever the Empiricism traces in the philosophy of the scope, feminist reworkings of empiricism have global North as far back as Aristotle,1 but it is two central themes. The first theme is the inter- classically associated with the 18th-century play among values in knowledge, especially British philosophers, John Locke, George connecting traditionally recognized empirical Berkeley, and David Hume. -

Anti-Metaphysics: 1. Agnosticism (Qv). 2. Logical Positivism (See Scientific Empiricism (1))

Anti-metaphysics: 1. Agnosticism (q.v.). 2. Logical Positivism (see Scientific Empiricism (1)) holds that those metaphysical statements which are not confirmable by experiences (see Verification 4, 5) have no cognitive meaning and hence are pseudo-statements (see Meaning, Kinds of, 1, 5). — R.C. Basic Sentences, Protocol Sentences: Sentences formulating the result of observations or perceptions or other experiences, furnishing the basis for empirical verification or confirmation (see Verification). Some philosophers take sentences concerning observable properties of physical things as basic sentences, others take sentences concerning sense-data or perceptions. The sentences of the latter kind are regarded by some philosophers as completely verifiable, while others believe that all factual sentences can be confirmed only to some degree. See Scientific Empiricism. — R.C. Formal: l. In the traditional use: valid independently of the specific subject-matter; having a merely logical meaning (see Meaning, Kinds of, 3). 2. Narrower sense, in modern logic: independent of, without reference to meaning (compare Semiotic, 3). — R.C. Intersubjective: Used and understood by, or valid for different subjects. Especially, i. lan- guage, i. concepts, i. knowledge, i. confirmability (see Verification). The i. character of science is especially emphasized by Scientific Empiricism (g. v., 1 C). —R.C. Meaning, Kinds of: In semiotic (q. v.) several kinds of meaning, i.e. of the function of an expression in language and the content it conveys, are distinguished. 1. An expression (sen- tence) has cognitive (or theoretical, assertive) meaning, if it asserts something and hence is either true or false. In this case, it is called a cognitive sentence or (cognitive, genuine) statement; it has usually the form of a declarative sentence. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice.