What Psychodynamic Psychotherapists Think About Free Will and Determinism and How That Impacts Their Clinical Practice : a Qualitative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Becoming a Pragmatic Researcher: the Importance of Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methodologies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 462 TM 035 389 AUTHOR Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J.; Leech, Nancy L. TITLE On Becoming a Pragmatic Researcher: The Importance of Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methodologies. PUB DATE 2003-11-00 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association (Biloxi, MS, November 5-7, 2003). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Pragmatics; *Qualitative Research; *Research Methodology; *Researchers ABSTRACT The last 100 years have witnessed a fervent debate in the United States about quantitative and qualitative research paradigms. Unfortunately, this has led to a great divide between quantitative and qualitative researchers, who often view themselves in competition with each other. Clearly, this polarization has promoted purists, i.e., researchers who restrict themselves exclusively to either quantitative or qualitative research methods. Mono-method research is the biggest threat to the advancement of the social sciences. As long as researchers stay polarized in research they cannot expect stakeholders who rely on their research findings to take their work seriously. The purpose of this paper is to explore how the debate between quantitative and qualitative is divisive, and thus counterproductive for advancing the social and behavioral science field. This paper advocates that all graduate students learn to use and appreciate both quantitative and qualitative research. In so doing, students will develop into what is termed "pragmatic researchers." (Contains 41 references.) (Author/SLD) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. On Becoming a Pragmatic Researcher 1 Running head: ON BECOMING A PRAGMATIC RESEARCHER U.S. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Philosophy As a Path to Happiness

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Philosophy as a Path to Happiness Attainment of Happiness in Arabic Peripatetic and Ismaili Philosophy Janne Mattila ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, University main building, on the 13th of June, 2011 at 12 o’clock. ISBN 978-952-92-9077-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7001-3 (PDF) http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/ Helsinki University Print Helsinki 2011 2 Abstract The aim of this study is to explore the idea of philosophy as a path to happiness in medieval Arabic philosophy. The starting point is in comparison of two distinct currents within Arabic philosophy between the 10th and early 11th centuries, Peripatetic philosophy, represented by al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā, and Ismaili philosophy represented by al-Kirmānī and the Brethren of Purity. These two distinct groups of sources initially offer two contrasting views about philosophy. The attitude of the Peripatetic philosophers is rationalistic and secular in spirit, whereas for the Ismailis philosophy represents the esoteric truth behind revelation. Still, the two currents of thought converge in their view that the ultimate purpose of philosophy lies in its ability to lead man towards happiness. Moreover, they share a common concept of happiness as a contemplative ideal of human perfection, merged together with the Neoplatonic goal of the soul’s reascent to the spiritual world. Finally, for both happiness refers primarily to an otherworldly state thereby becoming a philosophical interpretation of the Quranic accounts of the afterlife. -

The Transition from Studying Philosophy to Doing Philosophy

Teaching Philosophy 34:3, September 2011 241 The Transition from Studying Philosophy to Doing Philosophy JOHN RUDISILL The College of Wooster Abstract: In this paper I articulate a minimal conception of the idea of doing philosophy that informs a curriculum and pedagogy for producing students who are capable of engaging in philosophical activity and not just competent with a specific domain of knowledge. The paper then relates, by way of back- ground, the departmental assessment practices that have played a vital role in the development of my department’s current curriculum and in particular in the design of a junior-year seminar in philosophical research required of all majors. After a brief survey of the learning theory literature that has informed its design, I share the content of this junior-year seminar. In the paper’s conclusion I provide some initial data that indicates our approach to curriculum and pedagogy has had a positive impact on student achievement with respect to reaching the learning goals associated with “doing” as opposed to “merely studying” philosophy. 1. Introduction Capstone projects are common among liberal arts colleges and fre- quently carry an expectation that the final product demonstrates the student’s achievement of becoming a budding biologist, historian, sociologist, philosopher and so on. Even without a formal capstone requirement, I would hope that my philosophy students could—as they finish their undergraduate studies—demonstrate such an achievement. This is because the full set of benefits made available by an education in philosophy includes but extends well beyond knowledge of the history of philosophy and mastery of a philosophical lexicon. -

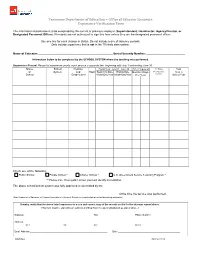

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Indeterminism in Physics and Intuitionistic Mathematics

Indeterminism in Physics and Intuitionistic Mathematics Nicolas Gisin Group of Applied Physics, University of Geneva, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland (Dated: November 5, 2020) Most physics theories are deterministic, with the notable exception of quantum mechanics which, however, comes plagued by the so-called measurement problem. This state of affairs might well be due to the inability of standard mathematics to “speak” of indeterminism, its inability to present us a worldview in which new information is created as time passes. In such a case, scientific determinism would only be an illusion due to the timeless mathematical language scientists use. To investigate this possibility it is necessary to develop an alternative mathematical language that is both powerful enough to allow scientists to compute predictions and compatible with indeterminism and the passage of time. We argue that intuitionistic mathematics provides such a language and we illustrate it in simple terms. I. INTRODUCTION I have always been amazed by the huge difficulties that my fellow physicists seem to encounter when con- templating indeterminism and the highly sophisticated Physicists are not used to thinking of the world as in- circumlocutions they are ready to swallow to avoid the determinate and its evolution as indeterministic. New- straightforward conclusion that physics does not neces- ton’s equations, like Maxwell’s and Schr¨odinger’s equa- sarily present us a deterministic worldview. But even tions, are (partial) differential equations describing the more surprising to me is the attitude of most philoso- continuous evolution of the initial condition as a func- phers, especially philosophers of science. Indeed, most tion of a parameter identified with time. -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Wittgenstein on Freedom of the Will: Not Determinism, Yet Not Indeterminism

Wittgenstein on Freedom of the Will: Not Determinism, Yet Not Indeterminism Thomas Nadelhoffer This is a prepublication draft. This version is being revised for resubmission to a journal. Abstract Since the publication of Wittgenstein’s Lectures on Freedom of the Will, his remarks about free will and determinism have received very little attention. Insofar as these lectures give us an opportunity to see him at work on a traditional—and seemingly intractable—philosophical problem and given the voluminous secondary literature written about nearly every other facet of Wittgenstein’s life and philosophy, this neglect is both surprising and unfortunate. Perhaps these lectures have not attracted much attention because they are available to us only in the form of a single student’s notes (Yorick Smythies). Or perhaps it is because, as one Wittgenstein scholar put it, the lectures represent only “cursory reflections” that “are themselves uncompelling." (Glock 1996: 390) Either way, my goal is to show that Wittgenstein’s views about freedom of the will merit closer attention. All of these arguments might look as if I wanted to argue for the freedom of the will or against it. But I don't want to. --Ludwig Wittgenstein, Lectures on Freedom of the Will Since the publication of Wittgenstein’s Lectures on Freedom of the Will,1 his remarks from these lectures about free will and determinism have received very little attention.2 Insofar as these lectures give us an opportunity to see him at work on a traditional—and seemingly intractable— philosophical problem and given the voluminous secondary literature written about nearly every 1 Wittgenstein’s “Lectures on Freedom of the Will” will be abbreviated as LFW 1993 in this paper (see bibliography) since I am using the version reprinted in Philosophical Occasions (1993). -

Is the Cosmos Random?

IS THE RANDOM? COSMOS QUANTUM PHYSICS Einstein’s assertion that God does not play dice with the universe has been misinterpreted By George Musser Few of Albert Einstein’s sayings have been as widely quot- ed as his remark that God does not play dice with the universe. People have naturally taken his quip as proof that he was dogmatically opposed to quantum mechanics, which views randomness as a built-in feature of the physical world. When a radioactive nucleus decays, it does so sponta- neously; no rule will tell you when or why. When a particle of light strikes a half-silvered mirror, it either reflects off it or passes through; the out- come is open until the moment it occurs. You do not need to visit a labora- tory to see these processes: lots of Web sites display streams of random digits generated by Geiger counters or quantum optics. Being unpredict- able even in principle, such numbers are ideal for cryptography, statistics and online poker. Einstein, so the standard tale goes, refused to accept that some things are indeterministic—they just happen, and there is not a darned thing anyone can do to figure out why. Almost alone among his peers, he clung to the clockwork universe of classical physics, ticking mechanistically, each moment dictating the next. The dice-playing line became emblemat- ic of the B side of his life: the tragedy of a revolutionary turned reaction- ary who upended physics with relativity theory but was, as Niels Bohr put it, “out to lunch” on quantum theory. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Being and Becoming-Ontology and the Conception of Evolution In

Part I: Foundationof Activify Theory Chapter2: Beingand Becoming-Ontologyand the Conceptionof Evolution in Activity Theory Pp.79-172 IN: Karpatsclrol.B. (1000).Human actit,ity. Contributions to the A nI hr op oI og i c'u I Sc' i en c e s .fr om a P er.s p ec t it,e of A ct iv i ty Theory. Copenlragen:Dansk Psykologisk Forlag. ISBN: 87 7706311 2. (Front.cover + xii + 513pages). Re-publishedriith acceptancefrom the authorand copyright- holder. PART I FOUNDATIONOF ACTIVITY THEORY 2. Beingand Becoming Ontology and the Conceptionof Evolution in Activity Theory As mentionedin thetirst chapter.this treatiseis abouta specificanthropo- loeicaltheor-v. Activitl'Theory'. In the flrst chapter.the historicaltradition of Activitv Theor.vu'as discussed. Before presenting the core of thetheory. how- eier. I uill intloduceand discuss its philclsophicalbasis. This philosophical tootingis ccrnrprisedof theba.irt' (onLept o.f reulitt andour knorletlg,eof tli.s realitt. The currentchapter presents the former.the onlo/ri,qr'.and chapter 3 presentsthe latter. the epistetrtologr. 2.1 Ontology Ontologr is thc'philosophicaldiscipline that erplores the question of beurg. Thus.the ontolog),'of Activin' Theori'mLlst ans\\'er such questions as. "What thingsexist iiroundhere'1" "Are thereditterent nrodes of eristence'1"Mclre- over.although episteurological in nature."How areue. thesub.ject.s discussing ontolog)-.relatecl to theerrlrtrr,r 'ul e arediscnssin-g'1" In principle.I u ill distinguishbenr,een Ihe object ntutlel'of ontologv (i.e.. the categorvof tlteotttit. and the content of ontolo-ufitself) and the ontolosi(ul (i.e..the description of theontic). This is in principal.because u'hen there is no dangerof confusion.