On Reality, Experience, and Truth: John Watson's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-23-2015 12:00 AM Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought Ben Woodard The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Tilottama Rajan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Joan Steigerwald The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Ben Woodard 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Woodard, Ben, "Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3314. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3314 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Benjamin Graham Woodard A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Theory and Criticism The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ben Woodard 2015 Abstract: This dissertation examines F.W.J. von Schelling's Philosophy of Nature (or Naturphilosophie) as a form of early, and transcendentally expansive, naturalism that is, simultaneously, a naturalized transcendentalism. -

Studia Philosophiae Religionis 21

STUDIA PHILOSOPHIAE RELIGIONIS 21 Editores: Catharina Stenqvist et Eberhard Herrmann Ulf Zackariasson Forces by Which We Live Religion and Religious Experience from the Perspective of a Pragmatic Philosophical Anthropology UPPSALA 2002 Doctoral Dissertation in Philosophy of Religion for the Degree of Doctor of Theology at Uppsala University 2002. ABSTRACT Zackariasson, Ulf. 2002. Forces by which We Live. Religion and Religious Experience from the Perspective of a Pragmatic Philosophical Anthropology. Studia Philosophiae Religionis 21. 254 pp. ISBN 91–628–5169–1. ISSN 0346–5446. This study argues that a pragmatic conception of religion would enable philosophers to make important contributions to our ability to handle concrete problems involving religion. The term ’philosophical anthropology’, referring to different interpretative frameworks, which philosophers draw on to develop conceptions of human phenomena, is introduced. It is argued that the classical pragmatists embraced a philosophical anthro- pology significantly different from that embraced by most philosophers of religion; accordingly, pragmatism offers an alternative conception of religion. It is suggested that a conception of religion is superior to another if it makes more promising contributions to our ability to handle extra-philosophical problems of religion. A pragmatic philosophical anthropology urges us to view human practices as taking shape as responses to shared experienced needs. Religious practices develop to resolve tensions in our views of life. The pictures of human flourishing they present reconstruct our views of life, thereby allowing more significant interaction with the environment, and a more significant life. A modified version of reflective equilibrium is developed to show how we, on a pragmatic conception of religion, are able to supply resources for criticism and reform of religious practices, so the extra-philosophical problems of religion can be handled. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Comment Fundamentalism and Science

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Comment Fundamentalism and science Massimo Pigliucci The many facets of fundamentalism. There has been much talk about fundamentalism of late. While most people's thought on the topic go to the 9/11 attacks against the United States, or to the ongoing war in Iraq, fundamentalism is affecting science and its relationship to society in a way that may have dire long-term consequences. Of course, religious fundamentalism has always had a history of antagonism with science, and – before the birth of modern science – with philosophy, the age-old vehicle of the human attempt to exercise critical thinking and rationality to solve problems and pursue knowledge. “Fundamentalism” is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of the Social Sciences 1 as “A movement that asserts the primacy of religious values in social and political life and calls for a return to a 'fundamental' or pure form of religion.” In its broadest sense, however, fundamentalism is a form of ideological intransigence which is not limited to religion, but includes political positions as well (for example, in the case of some extreme forms of “environmentalism”). In the United States, the main version of the modern conflict between science and religious fundamentalism is epitomized by the infamous Scopes trial that occurred in 1925 in Tennessee, when the teaching of evolution was challenged for the first time 2,3. That battle is still being fought, for example in Dover, Pennsylvania, where at the time of this writing a court of law is considering the legitimacy of teaching “intelligent design” (a form of creationism) in public schools. -

The Golden Cord

THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED ' " ' ..I ~·/ I _,., ' '4 ~ 'V . \ . " ': ,., .:._ C HARLE S TALIAFERR O THE GOLDEN CORD THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED CHARLES TALIAFERRO University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2012 by the University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taliaferro, Charles. The golden cord : a short book on the secular and the sacred / Charles Taliaferro. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04238-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04238-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. God (Christianity) 2. Life—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Self—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Redemption—Christianity. 5. Cambridge Platonism. I. Title. BT103.T35 2012 230—dc23 2012037000 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 Love in the Physical World 15 CHAPTER 2 Selves and Bodies 41 CHAPTER 3 Some Big Pictures 61 CHAPTER 4 Some Real Appearances 81 CHAPTER 5 Is God Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know? 107 CHAPTER 6 Redemption and Time 131 CHAPTER 7 Eternity in Time 145 CHAPTER 8 Glory and the Hallowing of Domestic Virtue 163 Notes 179 Index 197 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the patience, graciousness, support, and encour- agement of the University of Notre Dame Press’s senior editor, Charles Van Hof. -

Idealism and Realism in Western and Indian Philosophies

IDEALISM AND REALISM IN WESTERN AND INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES —Dr. Sohan Raj Tater Over the centuries the philosophical attitude in the west has never been constant but undulated between Idealism and Realism. The difference between these two appears to be irreconcilable, being more or less bound up with the innate difference of predispositions and tendencies varying from person to person. The result is an uncompromising antagonism. The western scholars, who were brought up in the tradition of Kant and Hegel, and who studied Indian philosophies, were more sympathetic towards the Idealistic systems of India. In the 19 th century, there was a predominant wave of monism and scholars like Max Muller were naturally attracted towards the metaphysical views of Sankara etc. and the uncompromising Monism of Vedanta was much admired as the cream of the oriental wisdom. There have been different Idealistic views in Western and Indian philosophies as follows : Western Idealism (i) Platonic Idealism The Idealism of Plato is objective in the sense that the ideas enjoy an existence in a real world independent of any mind. Mind is not antecedent for the existence of ideas. The ideas are there whether a mind reveals them or not. The determination of the phenomenal world depends on them. They somehow determine the empirical existence of the world. Hence, Plato’s conception of reality is nothing but a system of eternal, immutable and immaterial ideas. (ii) Idealism of Berkeley Berkeley may be said to be the founder of Idealism in the modern period, although his arrow could not touch the point of destination. -

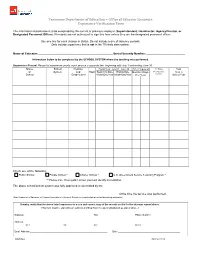

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

The Main Schools of Economic Thought

THE MAIN SCHOOLS OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT Level Initiation 5 Modules EDUCATION GOALS Understand the different schools of economic thought Recognise the key authors of the different schools of economic thought Be able to link the various theories to the school of thought that 3 H developed them Understand the contributions and the limitations of the different schools of economic thought WORD FROM THE AUTHOR « Economic reflections have existed since antiquity, emerging initially in Ancient Greece and then in Ancient China, where market production and an economy first appear to have been developed. Since 1800, different schools of economic thought have succeeded one another: the foundations of economic science first emerged via the two “precursors” of classical economic thought: the schools of mercantilism and physiocracy; the first half of the 19th century saw the birth of the classical school; while The Marxian school emerged during the second half of the 19th century; the neoclassical school is considered to be the fourth main school of economic thought. Finally, the last school of economic thought is the Keynesian school. In this course I invite you to examine these five schools of thought in detail: What are their theories? Who were the key authors of these schools? » ACTION ON LINE / Le Contemporain - 52 Chemin de la Bruyère - 69574 LYON DARDILLY CEDEX Tél : +33 (0) 4 37 64 40 10 / Mail : [email protected] / www.actiononline.fr © All rights reserved MODULES M181 – THE PRECURSORS Objectives education Understand mercantilism and its main authors Understand physiocracy and its main authors Word from the author « The mercantilist and physiocratic schools are often referred to as the precursors of classical economic thought. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Secular Fundamentalism and Democracy

Journal of Markets & Morality Volume 8, Number 1 (Spring 2005): 81–93 Copyright © 2005 Secular Richard Ekins Fundamentalism Lecturer at the Faculty of Law University of Auckland and Democracy New Zealand This article critiques the view, which may be termed secular fundamentalism, that democracy requires religious arguments and religious believers to be excluded from political discourse. Two objections are raised against secular fun- damentalism: First, it is premised on a flawed reading of the historical record that assumes religion and democracy are incompatible; second, it falsely assumes a stark division between religious (irrational) and secular (rational) reasons. The article goes on to propound a democratic model of church-state relations, prem- ised on the “twin tolerations” and priority for democracy. Finally, it is suggested that, in certain polities at least, stable democracy may require a religiously coherent rationale. Religious believers who organize collectively and who publicly advance argu- ments that rely on religious premises are often accused of engaging in inher- ently undemocratic political action. This article seeks to refute that charge, arguing instead that regimes that entrench secularism and exclude religious groups from participation in politics are not truly democratic. In what follows, I seek to establish that the intellectual framework that stipulates that religious believers ought to be excluded from politics is an absolutist doctrine that is inconsistent with a democratic interaction between church and -

Freewill and Determinism: the African Perspective and Experience

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.2, pp.75-82, February 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) FREEWILL AND DETERMINISM: THE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE AND EXPERIENCE Augustine Chidi Igbokwe, Department of Philosophy, Caritas University, Amorji – Nike P.M.B 01784, Enugu Enugu State – Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Whether Freewill and/or determinism has been an age long heated debate in the history of Western philosophy. The African metaphysical enquiry attempts a resolution by establishing a complementarity parlance between the two. Reality then becomes a paradox of harmony of opposites. In the midst of this harmony, a realization comes that the more a society turns modern, the more freedom is identified, subjecting deterministic tendencies to the periphery. As Africa is on the process to modernity, the system of communalism that had hitherto served Africa now gives way to individualism. In the same vein, there is need for a conscious change from unorganized but effective brotherhood to corporate and efficient governance to synergize this paradigm shift KEYWORDS: Freewill; Determinism; Communalism; Individualism; Free-Determinism. INTRODUCTION The philosophical argument on freewill and determinism which dates back to the ancient period still takes the front burner in our philosophical discourse today. How free are our actions and the choices we make? This question becomes pertinent when we juxtapose it with the long assumed assertion that every effect has a cause. If our actions as effects are all caused, then how morally responsible are we in our actions? This is usually the major paradox in the discourse on freewill and determinism and this is the major rationale behind the insistence on the heated debate.