Final Version: O'brien, LF (1996), 'Solipsism and Self-Reference'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING to IDEALISM Idealism As a Philosophy

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING TO IDEALISM Idealism as a philosophy had its greatest impact during the nineteenth century. It is a philosophical approach that has as its central tenet that ideas are the only true reality, the only thing worth knowing. In a search for truth, beauty, and justice that is enduring and everlasting; the focus is on conscious reasoning in the mind. The main tenant of idealism is that ideas and knowledge are the truest reality. Many things in the world change, but ideas and knowledge are enduring. Idealism was often referred to as “idea-ism”. Idealists believe that ideas can change lives. The most important part of a person is the mind. It is to be nourished and developed. Etymologically Its origin is: from Greek idea “form, shape” from weid- also the origin of the “his” in his-tor “wise, learned” underlying English “history.” In Latin this root became videre “to see” and related words. It is the same root in Sanskrit veda “knowledge as in the Rig-Veda. The stem entered Germanic as witan “know,” seen in Modern German wissen “to know” and in English “wisdom” and “twit,” a shortened form of Middle English atwite derived from æt “at” +witen “reproach.” In short Idealism is a philosophical position which adheres to the view that nothing exists except as it is an idea in the mind of man or the mind of God. The idealist believes that the universe has intelligence and a will; that all material things are explainable in terms of a mind standing behind them. PHILOSOPHICAL RATIONALE OF IDEALISM a) The Universe (Ontology or Metaphysics) To the idealist, the nature of the universe is mind; it is an idea. -

Science, Subjectivity & Reality

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Science and Religion Dialogue Prints Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research| April 2016 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | pp. 333-336 333 Pereira, C. & Reddy, J. S. K., On Science & Phenomenology in Consciousness Studies Perspective Science, Subjectivity & Reality * Contzen Pereira & J. S. K. Reddy Abstract In this paper, we argue on the ability of science to capture the true subjective experience of life, blinded within the limits of its reductionist approaches. With this approach, even though science can explain well the physics behind the objective phenomenon, it fails fundamentally in understanding the various aspects associated with the biological entities. In this sense, we are skeptical to the present approach of science and calls out for a more fundamental theory of life that considers not only the objectivity aspect of a biological entity but also the subjective experience as well. It raises questions as to what does it takes to develop a new science from a subjective standpoint. Key Words: Science, subjectivity, reality, cosmos, peripersonal space. Modern science is based on the principle “Give us one free miracle and we’ll explain the rest.” The one free miracle is the appearance of all the matter and energy in the universe and all the laws that govern it from nothing, in a single instant - Terrence McKenna The Cosmos showers the experience of life graced by an enigmatic subject grounded in an objective fabric (or biological structure). The extent of the subjective experience is in a way bounded by the limitations of an objective fabric. -

BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS I

i / REF1,l!;CTit.>NS ON ECONOMIC PROBLEMS / BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS ii ~FLECTIONS ON ECONO:MIC PROBLEMS 1 BY PLA'I'O, ARISTOTLE, JJJD AQUINAS, By EUGENE LAIDIBEL ,,SWEARINGEN Bachelor of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical Collage Stillwater, Oklahoma 1941 Submitted to the Depertmeut of Economics Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1948 iii f.. 'I. I ···· i·: ,\ H.: :. :· ··: ! • • ~ ' , ~ • • !·:.· : i_ ·, 1r 1i1. cr~~rJ3t L l: i{ ,\ I~ Y , '•T •)() 1 0 ,1 8 API-'HOV~D BY: .J ,.· 1.., J l.;"t .. ---- -··- - ·- ______.,.. I 7 -.. JI J ~ L / \ l v·~~ u ' ~) (;_,LA { 7 {- ' r ~ (\.7 __\ _. ...A'_ ..;f_ ../-_" ...._!)_.... ..." ___ ......._ ·;...;;; ··-----/ 1--.,i-----' ~-.._.._ :_..(__,,---- ....... Member of the Report Committee 1..j lj:,;7 (\ - . "'·- -· _ .,. ·--'--C. r, .~-}, .~- Q_ · -~ Q.- 1Head of the Department . · ~ Dean of the Graduate School 502 04 0 .~ -,. iv . r l Preface The purpose and plan of this report are set out in the Introduction. Here, I only wish to express my gratitude to Professor Russell H. Baugh who has helped me greatly in the preparation of this report by discussing the various subjects as they were in the process of being prepared. I am very much indebted to Dr. Harold D. Hantz for his commentaries on the report and for the inspiration which his classes in Philosophy have furnished me as I attempted to correlate some of the material found in these two fields, Ecor!.Omics and Philosophy. I should like also to acknowledge that I owe my first introduction into the relationships of Economics and Philosophy to Dean Raymond Thomas, and his com~ents on this report have been of great value. -

Philosophy of Science -----Paulk

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE -----PAULK. FEYERABEND----- However, it has also a quite decisive role in building the new science and in defending new theories against their well-entrenched predecessors. For example, this philosophy plays a most important part in the arguments about the Copernican system, in the development of optics, and in the Philosophy ofScience: A Subject with construction of a new and non-Aristotelian dynamics. Almost every work of Galileo is a mixture of philosophical, mathematical, and physical prin~ a Great Past ciples which collaborate intimately without giving the impression of in coherence. This is the heroic time of the scientific philosophy. The new philosophy is not content just to mirror a science that develops independ ently of it; nor is it so distant as to deal just with alternative philosophies. It plays an essential role in building up the new science that was to replace 1. While it should be possible, in a free society, to introduce, to ex the earlier doctrines.1 pound, to make propaganda for any subject, however absurd and however 3. Now it is interesting to see how this active and critical philosophy is immoral, to publish books and articles, to give lectures on any topic, it gradually replaced by a more conservative creed, how the new creed gener must also be possible to examine what is being expounded by reference, ates technical problems of its own which are in no way related to specific not to the internal standards of the subject (which may be but the method scientific problems (Hurne), and how there arises a special subject that according to which a particular madness is being pursued), but to stan codifies science without acting back on it (Kant). -

Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh

23 Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 17, Number 2. July 2020. Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder1, Abstract: This article traces back classical Greek and Medieval meanings of habitus to show that Bourdieu’s redefinition of habitus discarded a seminal feature of Aristotelian habitus—the power of radically transforming the self at will. I elaborate how the practices of purposefully training the embodied self remains marginalized in Pierre Bourdieu’s re-conceptualization of habitus. Examining Aristotle’s habitus, this paper brings back the focus on the long-neglected insight of the power of deliberately (re)training the self in constructing a heterodox but ethical way of being and socializing. As an example, I refer to the Fakirs in current Bangladesh, who cultivate antinomian life-practices. The main argument of the paper is that habitus in Bourdieu’s formulations is less suitable than Aristotle’s in analysing the praxis of the Fakirs. I suggest that instead of sticking to a universal conceptualization of habitus, sociologists should consider with equal importance both models of habitus articulated by Aristotle and Bourdieu. Doing that could benefit contemporary sociology in two ways: First, Aristotle’s conceptualization of habitus is an important tool in identifying the sociological importance of the praxis of marginalized groups, e.g., Fakirs in Bangladesh; and second, extending the focus of a key sociological concept, i.e., habitus, addresses the apparent disconnect between the wisdom of heterodox practitioners in the Global South and dominant social theories built upon the analyses of European and American social traditions. -

Hegel and Aristotle

HEGEL AND ARISTOTLE ALFREDO FERRARIN Boston University published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, vic 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Alfredo Ferrarin 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Baskerville 10.25/13 pt. System QuarkXPress™ 4.04 [AG] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ferrarin, Alfredo, 1960– Hegel and Aristotle / Alfredo Ferrarin. p. cm.–(Modern European philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-78314-3 1. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 1770–1831. 2. Aristotle – Influence. I. Title. II. Series. B2948 .F425 2000 193–dc21 00-029779 ISBN 0 521 78314 3 hardback CONTENTS Acknowledgments page xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 § 1. Preliminary Notes 1 § 2. On the Object and Method of This Book 7 § 3. Can Energeia Be Understood as Subjectivity? 15 part i the history of philosophy and its place within the system 1. The Idea of a History of Philosophy 31 § 1. The Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Editions and Sources 31 § 2. -

Dialectical Materialism and Subject: Monism and Dialectic

経済学論纂(中央大学)第57巻第 3 ・ 4 合併号(2017年 3 月) 243 Dialectical Materialism and Subject: Monism and Dialectic Hideki Shibata Introduction Chapter 1 Critique of Tadashi Kato Chapter 2 Sartre’s Theory of Subject Chapter 3 Language and Subject: the Social Origin of Transcendental Beings Conclusion Introduction I have translated three of Tadashi Kato’s articles (Kato 2014; Kato 2015; Kato 2016). In these articles, Kato seizes Marx’s monistic argument, but divides dialectics into the dialectic of cognition and the dialectic of objects, and finally turns to the dualism of cognition and the objective world because of Engels’ influence. Hegel’s dialectic was born as the identity of substance and subject (substance is subject) in its birthplace, the Phenomenology of Spirit, but this means the identity of being and cogni- tion.1) It does not mean that there are two kinds of dialectic. To overcome the dualism that remained after Kant was one of the principle themes of German Idealist Philosophy, and Marx also inherited this critically important issue. Marx’s monism, however, does not mean that “we must understand man as a being who produces himself and his world” (Landgrebe 1966, p. 10). Marx’s monism does not character- ize the world as the product of the constitutive operations of the human subject. Sartre un- derstood Marx’s real intention, and developed it in his articles (Cf. Omote 2014). In the con- clusion of Transcendence of the Ego, Sartre writes, “a working hypothesis as fruitful as historical materialism,” and follows it with a criticism of Engels’ materialism, which “never This paper owes much to the thoughtful and helpful comments and advices of the editor of Editage(by Cactus Communications). -

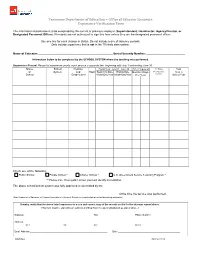

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Is Plato a Perfect Idealist?

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. V (Mar. 2014), PP 22-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Is Plato a Perfect Idealist? Dr. Shanjendu Nath M. A., M. Phil., Ph.D. Associate Professor Rabindrasadan Girls’ College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Abstract: Idealism is a philosophy that emphasizes on mind. According to this theory, mind is primary and objective world is nothing but an idea of our mind. Thus this theory believes that the primary thing that exists is spiritual and material world is secondary. This theory effectively begins with the thought of Greek philosopher Plato. But it is Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) who used the term ‘idealism’ when he referred Plato in his philosophy. Plato in his book ‘The Republic’ very clearly stated many aspects of thought and all these he discussed from the idealistic point of view. According to Plato, objective world is not a real world. It is the world of Ideas which is real. This world of Ideas is imperishable, immutable and eternal. These ideas do not exist in our mind or in the mind of God but exist by itself and independent of any mind. He also said that among the Ideas, the Idea of Good is the supreme Idea. These eternal ideas are not perceived by our sense organs but by our rational self. Thus Plato believes the existence of two worlds – material world and the world of Ideas. In this article I shall try to explore Plato’s idealism, its origin, locus etc. -

GALGAN, Gerald J., God and Subjectivity Roy Martinez

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:58 a.m. Laval théologique et philosophique GALGAN, Gerald J., God and Subjectivity Roy Martinez Volume 49, Number 1, février 1993 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/400749ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/400749ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculté de philosophie, Université Laval ISSN 0023-9054 (print) 1703-8804 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Martinez, R. (1993). Review of [GALGAN, Gerald J., God and Subjectivity]. Laval théologique et philosophique, 49(1), 166–167. https://doi.org/10.7202/400749ar Tous droits réservés © Laval théologique et philosophique, Université Laval, This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit 1993 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ COMPTES RENDUS observed. At the foundation of this study, and present This disparity between the existence of the "this" like a shadow throughout it, is the Platonic-Christian and the cognizing agent posed no problem for first view of time as an image of eternity, and of ourselves philosophy since 'the other", or object of cognition, as redeemed from time, and able in part to compre• was simply given, there for apprehension or obser• hend it, through being in the image of God.