Acta Geologica Polonica, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Late Cretaceous Jonathan Gaylor

40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Late Cretaceous Jonathan Gaylor To cite this version: Jonathan Gaylor. 40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Late Cretaceous. Earth Sciences. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2013. English. NNT : 2013PA112124. tel-01017165 HAL Id: tel-01017165 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01017165 Submitted on 2 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris Sud 11 UFR des Sciences d’Orsay École Doctorale 534 MIPEGE, Laboratoire IDES Sciences de la Terre 40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Late Cretaceous Thèse de Doctorat Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Jonathan GAYLOR Le 11 juillet 2013 devant le jury compose de: Directeur de thèse: Xavier Quidelleur, Professeur, Université Paris Sud (France) Rapporteurs: Sarah Sherlock, Senoir Researcher, Open University (Grande-Bretagne) Bruno Galbrun, DR CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie (France) Examinateurs: Klaudia Kuiper, Researcher, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Pays-Bas) Maurice Pagel, Professeur, Université Paris Sud (France) - 2 - - 3 - Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking my supervisor Xavier Quidelleur without whom I would not have finished, with special thanks on the endless encouragement and patience, all the way through my PhD! Thank you all at GTSnext, especially to the directors Klaudia Kuiper, Jan Wijbrans and Frits Hilgen for creating such a great project. -

Upper Cretaceous Stratigraphy and Biostratigraphy of South-Central New Mexico Stephen C

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/63 Upper Cretaceous stratigraphy and biostratigraphy of south-central New Mexico Stephen C. Hook, Greg H. Mack, and William A. Cobban, 2012, pp. 413-430 in: Geology of the Warm Springs Region, Lucas, Spencer G.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Lueth, Virgil W.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Krainer, Karl, New Mexico Geological Society 63rd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 580 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2012 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

The Turonian - Coniacian Boundary in the United States Western Interior

Acta Geologica Polonica, Vol. 48 (1998), No.4, pp. 495-507 The Turonian - Coniacian boundary in the United States Western Interior IRENEUSZ WALASZCZYKI & WILLIAM A. COBBAN2 I Institute of Geology, University of Warsaw, AI. Zwirki i Wigury 93, PL-02-089 Warszawa, Poland E-mail: [email protected] 270 Estes Street, Lakewood, Colorado 80226, USA ABSTRACT: WALASZCZYK, I. & COBBAN, W.A. 1998. The Turonian - Coniacian boundary in the United States Western Interior. Acta Geologica Polonica, 48 (4),495-507. Warszawa. The Turonian/Coniacian boundary succession in the United States Western Interior is characterized by the same inoceramid faunas as recognized in Europe, allowing the application of the same zonal scheme in both regions; Mytiloides scupini and Cremnoceramus waltersdorfensis waltersdorfensis zones in the topmost Turonian and Cremnoceramus deformis erectus Zone in the lowermost Coniacian. The correla tion with Europe is enhanced, moreover, by a set of boundary events recognized originally in Europe and well represented in the Western Interior: Didymotis I Event and waltersdorfensis Event in the topmost Turonian, and erectus I, II and ?III events in the Lower Coniacian. First "Coniacian" ammonite, Forresteria peruana, appears in the indisputable Turonian, in the zone of M. scupini, and the reference to Forresteria in the boundary definition should be rejected. None of the North American sections, pro posed during the Brussels Symposium as the potential boundary stratotypes, i.e. Wagon Mound and Pueblo sections, appears better than the voted section of the Salzgitter-Salder. The Pueblo section is relatively complete but markedly condensed in comparison with the German one, but it may be used as a very convenient reference section for the Turonian/Coniacian boundary in the Western Interior. -

Paleontology and Stratigraphy of Upper Coniacianemiddle

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2005 Paleontology and stratigraphy of upper Coniacianemiddle Santonian ammonite zones and application to erosion surfaces and marine transgressive strata in Montana and Alberta W. A. Cobban U.S. Geological Survey T. S. Dyman U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] K. W. Porter Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Cobban, W. A.; Dyman, T. S.; and Porter, K. W., "Paleontology and stratigraphy of upper Coniacianemiddle Santonian ammonite zones and application to erosion surfaces and marine transgressive strata in Montana and Alberta" (2005). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 367. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/367 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cretaceous Research 26 (2005) 429e449 www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes Paleontology and stratigraphy of upper Coniacianemiddle Santonian ammonite zones and application to erosion surfaces and marine transgressive strata in Montana and Alberta W.A. Cobban a,1, T.S. Dyman b,*, K.W. Porter c a US Geological Survey, Denver, CO 80225, USA b US Geological Survey, Denver, CO 80225, USA c Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Butte, MT 59701, USA Received 28 September 2004; accepted in revised form 17 January 2005 Available online 21 June 2005 Abstract Erosional surfaces are present in middle and upper Coniacian rocks in Montana and Alberta, and probably at the base of the middle Santonian in the Western Interior of Canada. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana ISSN: 1405-3322 Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. Ifrim, Christina Schlueterella stinnesbecki n. sp. (Ammonoidea, Diplomoceratidae) from the Turonian-Coniacian of northeastern Mexico Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, vol. 71, no. 3, 2019, September-December, pp. 841-849 Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18268/BSGM2019v71n3a13 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=94366148013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana / 2019 / 841 Short note Schlueterella stinnesbecki n. sp. (Ammonoidea, Diplomoceratidae) from the Turonian–Coniacian of northeastern Mexico Christina Ifrim ABSTRACT Christina Ifrim ABSTRACT RESUMEN [email protected] Institut für Geowissenschaften, Universität Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234, 69120 A new species of the genus Schlueterella Se describe una nueva especie del género Heidelberg, Germany. Wiedmann, 1962 is here described. Schlueterella Wiedmann, 1962. Los veinte Twenty specimens of this hetero- ejemplares de este ammonoideo heteromorfo morph ammonoid were collected fueron colectados en el norte de Coahuila, in northern Coahuila, Mexico. México. Parece que Schlueterella stinnes- Schlueterella stinnesbecki n. sp. seems to becki n. sp. fue una especie endémica en el have been an endemic form in the Turoniano tardío–Coniaciano temprano. late Turonian–early Coniacian. This Con total certeza se trata del registro más is the oldest definite record of the antiguo de este género y una forma básica genus and a basal form in its evolu- en su evolución desde Neocrioceras. -

Palaeontology of the Middle Turonian Limestones of the Nysa Kłodzka Graben

Palaeontology of the Middle Turonian limestones of the Nysa Kłodzka Graben... Geologos 18, 2 (2012): 83–109 doi: 10.2478/v10118-012-0007-z Palaeontology of the Middle Turonian limestones of the Nysa Kłodzka Graben (Sudetes, SW Poland): biostratigraphical and palaeogeographical implications Alina Chrząstek Institute of the Geological Sciences, Wrocław University, Maksa Borna 9, PL 50-204 Wrocław, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The ammonites Lewesiceras peramplum Mantell and ?Lewesiceras sp. are reported from the Upper Cretaceous in the Nysa Kłodzka Graben; they date from the Middle Turonian and ?Coniacian, respectively. The Middle Turonian lime- stones of the Stara Bystrzyca quarry contain an abundant assemblage of inoceramids (Inoceramus cuvieri Sowerby and I. lamarcki Parkinson) and other bivalves, including oysters, as well as brachiopods and trace fossils. Micropalaeonto- logical data show the presence of foraminifers and siliceous sponge spiculae, bryozoans, ostracods and fragments of bivalves and gastropods. The Middle Turonian calcareous deposits belongs to the upper part of the Inoceramus lamarcki Zone (late Middle Turonian) and were deposited on a shallow, subtidal offshore shelf. They overlie the Middle Turo- nian Bystrzyca and Długopole Sandstones, which represent foreshore-shoreface delta deposits. The fossil assemblage suggests a moderate- to low-energy, normal-salinity environment with occasionally an oxygen deficit. Keywords: Middle Turonian, Sudetes, Nysa Kłodzka Graben, ammonites, inoceramids, biostratigraphy 1. Introduction Stara Bystrzyca quarry. It is, with its diameter of approx. 45 cm, probably the biggest ammo- Representatives of the ammonite genus nite ever found in Nysa Kłodzka Graben and Lewesiceras are most typical of the Middle-Late probably also in the Sudety Mountains (Fig. -

General Trends in Predation and Parasitism Upon Inoceramids

Acta Geologica Polonica, Vol. 48 (1998), No.4, pp. 377-386 General trends in predation and parasitism upon inoceramids PETER 1. HARRIES & COLIN R. OZANNE Department of Geology, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Ave., SeA 528, Tampa, FL 33620-5201 USA. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: HARRIES, P.I. & OZANNE, C.R. 1998. General trends in predation and parasitism upon inoceramids. Acta Geologica Polonica, 48 (4), 377-386. Warszawa. Inoceramid bivalves have a prolific evolutionary history spanning much of the Mesozoic, but they dra matically declined 1.5 Myr prior to the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Only the enigmatic genus Tenu ipteria survived until the terminal Cretaceous event. A variety of hypotheses have attempted to expla in this disappearance. This study investigates the role that predation and parasitism may have played in the inoceramids' demise. Inoceramids show a range of predatory and parasitic features recorded in their shells ranging from extremely rare bore holes to the parasite-induced Hohlkehle. The stratigraphic record of these features suggests that they were virtually absent in inoceramids prior to the Late Turonian and became increasingly abundant through the remainder of the Cretaceous. These results suggest that predation and parasitism may have played a role in the inoceramid extinction, but more rigorous, quantitative data are required to test this hypothesis further. Probably the C011lmonest death for many animals is to be ous-Tertiary boundary (KAUFFMAN 1988). The mar eaten by something else. ked demise of such an important group has led to the C. S. Elton (1927) formulation of a wide range of hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. -

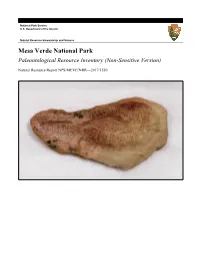

Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version)

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 ON THE COVER An undescribed chimaera (ratfish) egg capsule of the ichnogenus Chimaerotheca found in the Cliff House Sandstone of Mesa Verde National Park during the work that led to the production of this report. Photograph by: G. William M. Harrison/NPS Photo (Geoscientists-in-the-Parks Intern) Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resources Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 G. William M. Harrison,1 Justin S. Tweet,2 Vincent L. Santucci,3 and George L. San Miguel4 1National Park Service Geoscientists-in-the-Park Program 2788 Ault Park Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45208 2National Park Service 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove, Minnesota 55016 3National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 4National Park Service Mesa Verde National Park PO Box 8 Mesa Verde CO 81330 November 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Jurassic and Cretaceous Macrofossils from Sheet 266 (Marlborough): Autumn 2011

?Jurassic and Cretaceous macrofossils from Sheet 266 (Marlborough): Autumn 2011 Science, Geology & Landscape Programme Internal Report IR/11/072 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SCIENCE, GEOLOGY & LANDSCAPE PROGRAMME INTERNAL REPORT IR/11/072 ?Jurassic and Cretaceous macrofossils from Sheet 266 (Marlborough): Autumn 2011 The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. M A Woods Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords ?Jurassic, Cretaceous, Chalk Group, macropalaeontology, lithostratigraphy, chronostratigraphy, biostratigraphy, Cenomanian, Coniacian. Map Sheet 266, 1: 50 000 scale, Marlborough Bibliographical reference WOODS, M A. 2011. ?Jurassic and Cretaceous macrofossils from Sheet 266 (Marlborough): Autumn 2011. British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/11/072. 20pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. © NERC 2011. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2011 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Numbers in italic indicate figures, numbers in bold indicate tables abiotic environment change 43 Anticosti Island, Qu6bec Acanthocythereis meslei meslei 298, 304, 305 conodont fauna 73-100 Achilleodinium 263 geology 74 Achmosphaera 263 Anticostiodus species 93, 99 Achmosphaera alcicornu 312, 319 Aphelognathus grandis 79, 83-84 Acodus delicatus 50 Apiculatasporites variocorneus 127, 128 acritarch extinction 28, 29 Apiculatisporites verbitskayae 178, 182 Actinoptychus 282, 286, 287 Apsidognathus tuberculatus 96 Actinoptychus senarius 280, 283, 284, 287 Apteodinium 263 adaptation, evolutionary 35 Araucariacites 252 A dnatosphaeridium 312, 314, 321 Archaeoglobigerina blowi 220, 231,232 buccinum 261,264 Archaeoglobigerina cretacea 221 Aequitriradites spinulosus 180, 182 Arctic Basin Aeronian Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary 137-171, 136 conodont evolutionary cycles 93-96 palaeobiogeography 162, 165, 164, 166, 170 sea-level change 98-100 palaeoclimate 158-160 age dating, independent 237 Aren Formation, Pyrenees 244, 245 age-dependency, Cenozoic foraminifera 38-39, Arenobulimina 221,235 41-44 Areoligera 321 Ailly see Cap d'Ailly coronata 264 Alaska, Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary, medusettiformis 264, 263, 259 stratigraphy 155-157 Areosphaeridium diktyoplokum 315, 317, 319 Alatisporites hofjmeisterii 127, 128, 129 Areosphaeridium michoudii 314, 317 Albiconus postcostatus 54 Argentina, Oligocene-Miocene palynomorphs Aleqatsia Fjord Formation, Greenland 92 325-341 Alterbidinium 262 Ashgillian Ammobaculites lobus 147, 149, 153, 155, 157 -

A Late Cretaceous Mosasaur from North-Central New Mexico

New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 46th Field Conference, Geology of the Santa Fe Region, 1995 257 A LATE CRETACEOUS MOSASAUR FROM NORTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO SPENCER G. LUCASl, ANDREW B. HECKERT2 and BARRY S. KUES2 New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Road N.W., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87104; 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87l31-1116 Abstract-We describe a partial vertebral column of a mosasaur identified as cf. Tylosaurus sp. from the lower Niobrara interval of the Mancos Shale south of Galisteo in Santa Fe County, New Mexico. Invertebrate fossils collected from the same horizon include the inoceramids cf. Inoceramus (Cremnoceramus) deformis and cf. Inoceramus (Platyceramus ) platinus and dense growths of the oyster Pseudoperna congesta. They suggest a Coniacian age. This is the oldest documented mosasaur from New Mexico. INTRODUCTION more, comparison of NMMNH P-22142 to Williston's (1898) plates Mosasaurs were marine lizards of the Late Cretaceous that first ap shows that in Tylosaurus the rib articulations on the dorsal vertebrae are peared during the Cenomanian (Russell, 1967, 1993). Although marine large, dorsally positioned and circular in cross section. NMMNH P-22142 Upper Cretaceous strata are widely exposed in New Mexico, the fossil is also very similar to specimens of Tylosaurus proriger illustrated by record of mosasaurs from the state is limited to a handful of documented Williston (1898, pIs. 62, 65, 72) in that no traces of a zygosphene occurrences (Lucas and Reser, 1981; Hunt and Lucas, 1993). Here, we zygantrum articulation can be seen on any of the vertebrae, and the neu add to this limited record notice of incomplete remains of a mosasaur ral spines are very long antero-posteriorly so that their edges almost meet. -

Integrated Biostratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Abderaz Formation of the East Kopet Dagh Basin (NE Iran)

GEOLOGICA BALCANICA, 41. 1–3, Sofia, Dec. 2012, p. 21–37. Integrated biostratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous Abderaz Formation of the East Kopet Dagh Basin (NE Iran) Meysam Shafiee Ardestani1, Mohammad Vahidinia1, Abbas Sadeghi2, José Antonio Arz3, Docho Dochev4 1 Faculty of Science, Department of Geology, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Shahid Beheshti, Tehran, Iran 3 Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra (Paleontología) e Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Ambientales (IUCA), Universidad de Zaragoza, C/ Pedro Cerbuna 12, E-50009 Zaragoza, Spain 4 Department of Geology, Paleontology and Fossil Fuels, Faculty of Geology and Geography, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Sofia, Bulgaria (Accepted in revised form: November2012) Abstract. Based on planktonic foraminifera, inoceramids and echinoids, we present a detailed biostratigraphic analysis of the Abderaz Formation at the 606 m thick Padeha section, NE Iran. This sequence consists mainly of gray shales and marls with four levels of chalky limestones intercalated. The lower boundary of the Abderaz Formation with the Aitamir Formation is a paraconformity, while the upper boundary with the Abtalkh Formation represents a gradual transition. Fifty four species of planktonic foraminifera from 15 genera were identified, and five zones were recognized, namely: Whiteinella archaeocretacea (Bolli) Partial-Range- Zone; Helvetoglobotruncana helvetica (Sigal) Total-Range-Zone; Marginotruncana schneegansi (Dalbiez) Interval-Range-Zone; Dicarinella concavata (Brotzen) Interval-Range-Zone; and Dicarinella asymetrica (Sigal) Total-Range-Zone. Based on these data, the age of the Abderaz Formation is determined as earli- est Turonian to earliest Campanian. Inoceramid bivalves Cremnoceramus walterdorfensis walterdorfensis (Andert) and Cremnoceramus deformis deformis (Meek) were identified in the uppermost Turonian and in the middle part of the early Coniacian, respectively.