COMPETIZIONE DAYTONAS, from $300,000 to $2,000,000 by Michael Sheehan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REV Entry List

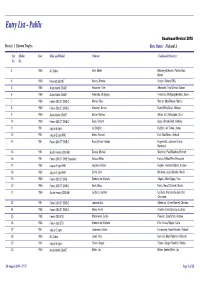

Entry List - Public Goodwood Revival 2018 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy - Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 3 1963 AC Cobra Hunt, Martin Blakeney-Edwards, Patrick/Hunt, Martin 4 1960 Maserati 3500GT Rosina, Stefano Rosina, Stefano/TBC, 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Wilmott, Adrian 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Friedrichs, Wolfgang/Hadfield, Simon 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Werner, Max Werner, Max/Werner, Moritz 8 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Allemann, Benno Dowd, Mike/Gnani, Michael 9 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Mosler, Mathias Gillian, G.C./Woodgate, Chris 10 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Reid, Anthony 11 1961 Jaguar E-type Ian Dalglish Dalglish, Ian/Turner, James 12 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Huff, Rob/Meins, Richard 14 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Hugenholtz, John/van Oranje, Bernhard 15 1961 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Darcey, Michael Woolmer, Paul/Woolmer, Richard 16 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB 'Breadvan' Halusa, Niklas Halusa, Niklas/Pirro, Emanuele 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Corrie, John Minshaw, Jason/Stretton, Martin 19 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Scuderia del Viadotto Vögele, Alain/Vögele, Yves 20 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 21 1960 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Le Blanc, Karsten Le Blanc, Karsten/van Lanschot, Christiaen 23 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Lanzante Ltd. Ellerbrock, Olivier/Glaesel, Christian -

In Stock: Seeking to Acquire for Ready Customers

3300 Southwest 14th Place Boynton Beach, FL 33426 TEL: 561 509 7251 / CELL: 203 981 9444 / FAX: 561 892 2201 EMAIL: [email protected] OCTOBER 1, 2020 IN STOCK: 1967 JAGUAR XKE ROADSTER. BR GREEN - TAN. SUPERB HI QUALITY RESTORATION. MULTIPLE AWARDS $225,000 1964 JAGUAR XKE ROADSTER, SILVER SAND -TOBACCO. FULL RESTORATION BY PREDATOR. PERFECT $238,000 1954 JAGUAR XK120 SE. BLACK – RED. PERIOD COMPETITION MODS AND EARLY RACE HIST $165,000 1999 FERRARI 360 MODENA F1. RED – BLK. 1500 ORIGINAL MILES. FULLY SERVICED. PERFECT. AS NEW INQUIRE 1992 FERRARI F40, RED-RED, 9300 MILES. 1992 US PRODUCTION 1 OF 22. CLASSICHE, PLATINUM SOLD 1974 FERRARI 365 GTB-S4. LO MILES, BLACK. DAYTONA SPIDER CONVERSION. “A”TYPE, EURO. INQUIRE 1972 FERRARI 365 GTB4 DAYTONA, RED – BLK. FULLY RESTORED. THREE TIMES PLATINUM. PERFECT INQUIRE 1971 FERRARI DINO 246, BLUE “SERA” – TAN. RARE “L” MODEL, FULLY RESTORED. PLATINUM $425,000 1974 FERRARI 365 BB4, FLY YELLOW – BLACK, FIRST OF THE BOXERS, RESTORED TO PLATINUM SOLD 1976 FERRARI 308 GT4, BLUE SERA WITH BLACK LEATHER. EXCEPTIONAL DRIVER SOLD 1994 FERRARI 512 TR, RED – TAN, RECENT MAJOR SERVICE. EURO VERSION $135,000 1960 ALFA ROMEO 1300 GT SPIDER VELOCE. SILVER – RED. IN RESTORATION SOLD 1966 ALFA ROMEO 1600 GTA. RED. ORIGINAL 1600. FRESH REBUILD. ORIGINAL CAR, GREAT HISTORY INQUIRE 1965 ALFA ROMEO 2600 SZ. ZAGATO COUPE. IN RESTORATION INQUIRE 1993 LAMBORGHNI DIABLO. RED – BLK. 3000 ORIG MILES. FULLY SERVICED INQUIRE 1967 MASERATI GHIBLI COUPE. 4.7 LITER. DARK BLUE – TAN. RESTORED. VERY EARLY CAR INQUIRE 1977 PANTHER J72, CREAM - TAN. MODERN REPRODUCTION OF THE CALSSIC JAGUAR SS 100 57,500 1956 PORSCHE 356A SPEEDSTER, DARK GREEN – TAN. -

The Great American Car Revival Words and Photography by Howard Koby

SPECIAL EVENT : 2007 COPPERSTATE 1000 Seventeenth Annual Copperstate 1000 Road Rally THE GREAT AMERICAN CAR REVIVAL WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY HOWARD KOBY or 17 years the Men’s Art Council of the Phoenix Art Museum has been F giving vintage car enthusiasts the opportunity to exercise their machinery while enjoying some of the best scenery in the Southwest. On April 14, 2007, two car shows united at Tempe Diablo Stadium (home of spring training for the Los Angeles Angels baseball team). The Concorso Arizona, celebrating 60 years of Ferrari, was held in conjunction with the sendoff of the Copperstate 1000 Road Rally. Ferrari Club of America’s Concorso lined the field of the stadium with 120 exotic Italian vehicles. Concorso Arizona is the largest Ferrari gathering in Arizona and is the only IFC/PCA judged event in the state. Ferrari, Lamborghini, Jaguar, Aston Martin, Maserati, and Alfa Romeo owners were invited from around the country to proudly display their treasures in a “Field of Dreams” setting. Some lesser-known names such as Allard, Kurtis and Frazier-Nash added to the wide-range of cars on display. While the key purpose for many of these car shows is raising money for worthy charities like the Ronald McDonald House and the Phoenix Art Museum, having a good time is also part of the package. Judging was available for any 1997 or older Ferrari, and at the same time the blending of the concours and the Concorso Arizona — Tempe Diablo Stadium Copperstate entries created a new and Concorso Arizona — 1962 Ferrari Spyder CA — Chris Cox exciting visual treat for the hundreds of 1952 212 Ferrari Barchetta — Bill Jacobs spectators who showed up Saturday and 1960 Lotus Type 14 Elite — Jess and Eddie Marker — Copperstate sendoff from stadium 18 • September-October 2007 • ARIZONADRIVER ARIZONADRIVER • September-October 2007 • 19 Sunday morning. -

A Preliminary Study of University Students' Collaborative Learning Behavior Patterns in the Context of Online Argumentation Le

A Preliminary Study of University Students’ Collaborative Learning Behavior Patterns in the Context of Online Argumentation Learning Activities: The Role of Idea-Centered Collaborative Argumentation Instruction Ying-Tien Wu, Li-Jen Wang, and Teng-Yao Cheng [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Graduate Institute of Network Learning Technology, National Central University, Taiwan Abstract: Learners have more and more opportunities to encounter a variety of socio-scientific issues (SSIs) and they may have difficulties in collaborative argumentation on SSIs. Knowledge building is a theory about idea-centered collaborative knowledge innovation and creation. The application of idea-centered collaboration practice as emphasized in knowledge building may be helpful for facilitating students’ collaborative argumentation. To examine the perspective above, this study attempted to integrate idea-centered collaboration into argumentation practice. The participants were 48 university students and were randomly divided into experimental and control group (n=24 for both groups). The control group only received argumentation instruction, while the experimental group received explicit idea-centered collaborative argumentation (CA) instruction. This study found that two groups of students revealed different collaborative learning behavior patterns. It is also noted that the students in the experimental group benefited more in collaborative argumentation from the proper adaption of knowledge building and explicit idea-centered collaborative argumentation instruction. Introduction In the knowledge-based societies, learners have more and more opportunities to encounter a variety of social dilemmas coming with rapid development in science and technologies. These social dilemmas are often termed “Socio-scientific issues (SSIs)” which are controversial social issues that are generally ill-structured, open-ended authentic problems which have multiple solutions (Sadler, 2004; Sadler & Zeidler, 2005). -

1966 Ferrari 330 Gtc Lhd

1966 FERRARI 330 GTC LHD D E T A I L S Year: 1966 Conguration: LHD Price: SOLD D E S C R I P T I O N The Ferrari 330 GTC offered here was constructed in 1966 and sold to a Mr Milos via Franco- Britannic Autos, of Paris, France. Mr Milos retained the car for the next 17 years before selling it to another French resident, a Mr Jean-Francois Thoviste, of Boug-de-Thizy. The car remained with its second owner for the next 31 years before being sold in 1997 to a noted Ferrari collector by which time it had travelled only 15,000 kms from new. Purchased in partly restored condition by JD Classics in 2015, this GTC is currently benetting from a full restoration by marque specialists Le Coq and is being returned to its factory original colour specication of Grigio Argento bodywork and black Franzi leather interior. With full matching numbers, excellent provenance and offered in immaculate condition this example will provide the new owner with an excellent opportunity to acquire one of the most useable and stylish of Ferraris of the Enzo era. Please contact us for further details, price on application. The Ferrari 330 range was introduced in 1963 as a successor to the famous Ferrari 250. The rst model, the 330 America, was little more than a 250 GT/E with a larger engine and was quickly replaced by the 330 GT 2+2 in January 1964. This was an entirely new car with a redesigned nose and tail, four headlights, a wider grille, longer wheel base and adjustable koni shock absorbers. -

NASA Club Codes and Regulations

3/25/2021 2:24 PM CLUB CODES AND REGULATIONS Ó1989 - 2021 2021.8.3 EDITION © THIS BOOK IS AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL AUTO SPORT ASSOCIATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NOTE- MID-SEASON UPDATES MAY BE PUBLISHED. PLEASE NOTE THE VERSION NUMBER ABOVE. THE CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK ARE THE SOLE PROPERTY OF THE NATIONAL AUTO SPORT ASSOCIATION. NO PORTION OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY MANNER, ELECTRONICALLY TRANSMITTED, POSTED ON THE INTERNET, RECORDED BY ANY MEANS, OR STORED ON ANY MAGNETIC / ELECTROMAGNETIC STORAGE SYSTEM(S) WITHOUT THE EXPRESS WRITTEN CONSENT FROM THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL AUTO SPORT ASSOCIATION. NOTE- THE VERSION POSTED ON THE WEBSITE MAY BE PRINTED FOR PERSONAL USE. National Auto Sport Association National Office 7065 A Ann Rd. #130 - 432 Las Vegas, NV 89130 http://www.nasaproracing.com 510-232-NASA 510-277-0657 FAX Author: Jerry Kunzman Editors: Jim Politi and Bruce Leggett ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 TERMINOLOGY AND DEFINITIONS 3 1.1 Activities 3 1.1.1 High Performance Driving Event (HPDE) 3 1.1.2 Driving School 3 1.1.3 Open Track 3 1.1.4 Competition 3 1.1.5 Time Trial / Time Attack 3 1.1.6 Other NASA Activities 3 1.2 Facility Terminology 4 1.2.1 Racetrack 4 1.2.2 Restricted Area 4 1.2.3 Re-Entry (Head of Pit lane) 4 1.2.4 Hot Pits 4 1.2.5 Paddock / Pre-Grid 4 1.2.6 Cold Pits 4 1.2.7 Pitlane 4 1.2.8 Aerial Photography 4 1.3 Membership Definitions 4 1.3.1 Member 4 1.3.2 Membership – Terms and Conditions 4 1.3.3 Membership - Associate 5 1.3.4 Member Car Club Insurance 5 1.3.5 Membership Renewal -

1996 Ferrari FX 1981 BMW M1 1950 Ferrari 195S 1989 Lamborghini

1996 Ferrari FX 1982 DeLorean DMC12 1991 Ferrari F40 The Sultan of Brunei commissioned If it weren’t for the lm Back to the It was built to celebrate Ferrari’s 40th legendary Italian designer Future, the DMC12 would’ve died with the anniversary and held the title Pininfarina to design six one-of-a- company. Luckily, he director didn’t want to as the world’s fastest kind Ferraris. This is No. 4 of the use a refrigerator for a time machine out street-legal production car. secret six and the only one to make of fear children would get hurt at home it out of the jungle. trying to travel through time. 1981 BMW M1 1965 Ford Shelby GT350 1988 Ducati Senna Special One of the rarest BMW models ever made The real Eleanor. Have you ever seen Custom built for the late Ayrton Senna and their rst ever sport car. the movie Gone in 60 Seconds? who won three Formula One World Lamborghini entered an Well, those engine noises your Championships in his short career. agreement with BMW to build a drooled over from Eleanor, came production race car but after a few disagreements, from this Shelby GT350. BMW launched the M1 themselves. 1950 Ferrari 195S 1972 Ferrari Dino 246 GT 1979 GTS 90 Ducati Dick Marconi and his son raced this vintage This 246 GT is a VERY rare coupe with It underwent a 4 year restoration process Ferrari at the prestigious Millie Miglia race the Chair & Flair option. with custom pipes, tanks and more. in Italy. -

South Jersey Region SCCA Lightning Challenge Regional Races

South Jersey Region SCCA Eleventh Annual Lightning Challenge Regional Races Presented by Blue Knob Auto Sales New Jersey Road Racing Series – Round 3&4 MARRS - Round 4 Northeast Division Road Racing Championship- Round 3 North American Formula 1000 Championship - Round 3&4 Right Coast Formula F Series - Round 1 US Touring Car Championship – Round 1 June 1-3, 2018 New Jersey Motorsports Park Lightning Supporting www.SJR-SCCA.org ~ www.NEDiv.com ~ www.SCCA.com www.blueknobauto.com ~ www.njrrs.com ~ www.rcffs.org ~ naf1000.com 18-PD-5500-S South Jersey Region 18-RQ -5501-S Eleventh Annual Lightning Challenge 2-3 June 2018 18-R-5502-S SUPPLEMENTAL REGULATIONS 18-ADS-5784-S 18-PDX-5785-S T e s t Groups R a ce G ro u p s Group 1 - Closed wheel – Big Bore Group 1 - GT1 GT2 GT3,GTA,ASR,AS,ITE,T1,T2,SPO,GTSC Group 2 - PDX 1 Group 2 - SSM Group 3 - Open wheel, Prototype Group 3 - FA,FB,FC,FE,FM,FS,CFC,P1,P2,S2,VS2,HS2,F1000 Group 4 - SR, SRF Group 4 - T3,T4,ITA,IT7,EP,FP,HP,LC,GTP,GTL,SPU,STU, Group 5 - PDX 2 Group 5 - SRF3,SRF,SR Group 6 - Closed Wheel – SM, SSM, Small Bore Group 6 - ITR,ITS,ITB,ITC,LCC,SB,STL,SM 2,SRX7,BSpec Group 7 - FF,F500,FV,FST,CF,RCFFS Groups and Schedule are subject to change Group 8 - SM,SMT,SM 5 based on number of entries Group 9 – F1000 Championship (Sunday only) Group 10 – USTCC (Sunday only) Thursday - 31 May 2018 Registration - 7:00 pm - 9:00 pm Tech - 7:00 pm - 9:00 pm SCHEDULE FRIDAY - 1 June 2018 SATURDAY - 2 June 2018 SUNDAY - 3 June 2018 Registration Lightning Classroom Lightning Classroom Lightning Classroom -

Herbicide Group Classification

Herbicide Group Classification Limiting the resistance of weeds to herbicides is a b ig concern for most farmers. Herbicide resistance leads to reduced yields, increased control costs and stress. Traditionally herbicide resistance develops when a producer uses the same herbicide or herbicides with the same mode of action repeatedly over some time. Depending on the cropping system, weeds present and the herbicides used, resistance can develop quickly. In corn production, the presence of triazine resistant lamb’s quarters and pigweed is well documented. They originated with the continuous use of atrazine based products over several years. As a result, similar herbicides, with the same mode of action as atrazine can be ineffective against some of these populations. In recent years, fields in the mid western United States, that have been in continuous Roundup Ready corn and soybean rotations, are showing several glyphosate resistant weed species. There are several ways to minimize herbicide resistance development: Using robust crop rotations, integrating physical weed control strategies (tillage) and rotating herbicides with different modes of action. Herbicide rotation is not as easy as it sounds. Simply using a different herbicide may not give the desired effect of mode of action rotation. Using two different herbicides, with the same mode of action, could illicit the same resistance response in a particular weed. For example, switching from atrazine to simazine may still encourage triazine resistance, as they are both triazines and have similar modes of action. Mode of action: The mode of action indicates the way that a pesticide works to stop the normal function of the pest, and eventually suppress or even kill the pest. -

FCA Added Member Benefits Ferraris, Fun and Bucks Back!

2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Hello FCA Southwest Region Members, “I am a member of “The Ferrari Club of America, Southwest Region.” What does that mean? To me it means I’m a member of the best car club anyone could be a member of. It means I get to meet people who share the same pas - sion I have for my favorite Italian car. It means I have made lasting friends and relationships. It means I get to see cars under normal circumstances I would never see. It means I have ample opportunity to drive my car on the track, with plenty of opportunities to go on scenic drives for the day –the weekend –and sometimes longer that that. It means I get to display my car in numerous concours, and have the opportunity to win trophies and awards. And It means about 25+ more items that I can add to the list. I bet you can even think of more than that. It’s so much more than just a car club, it’s an ability to participate in a life style that we all are so fortunate to have the means to do so. That’s what it is to me. Think about it, see what it means to you. We have a fantastic year of events coming up. By the time you are reading this, the Holiday Party, Kart racing, The Tech Inspection at South Bay Ferrari, The Nethercutt Collection, the Mullin Museum Run, and the Enzo Cruise In event would have passed. Up coming is The Ortega Run, the Willow Springs Driving School, the McDonald’s to McDonnell Douglas Run, and The Rancho Los Alamitos Run. -

Sonoma-Provisional-R

SVRA Sonoma Historic Motorsports Festival SVRA Sonoma Raceway, Sonoma, CA May 31 – June 3, 2018 Provisional Schedule Track Length: 2.52 miles Wednesday, May 30 Saturday cont. 12:00pm—5:00pm Registration & Load-in 11:40am Trans Am Testing 2 40min Thursday, May 31 7:00am—5:00pm Registration 12:20pm - 1:20pm LUNCH BREAK 7:30am—5:00pm Tech Inspection-Test Day/DOP/TOP Participants 12:20pm – 12:50pm Jaguar Consumer Pro Laps plan Tech by 3:00pm. After 3pm, priority to 1st 4 Run 12:50pm - 1:20pm Prewar Exhibition Laps Groups of Friday Schedule. 7:30am—Mandatory test day drivers’ mtg, 1:20pm Group 9 Feature Race 1 (grandstands near winners’ circle) 1:50pm Group 6 Feature Race 1 8:10am—5:10pm TEST DAY (separate schedule on other side) 2:20am Group 5 Feature Race 1 2:50pm Group 12 Feature Race 1 Friday, June 1 3:20pm Group 11 Feature Race 1 7:00am--5:00pm Registration 3:50pm Trans Am Practice (split) 40min 7:00am-11:30am / 1:30pm-5:00pm Tech Inspection 4:20pm Stage selected cars for at front gate for parade to Sonoma 7:30am MANDATORY DRIVERS’ MEETING 4:30pm End of on-track activities (grandstands near winners’ circle) 5:10pm Depart for Sonoma Town Square Historic Festival 8:10am Group 5 Practice 8:30am Group 4 Practice Sunday, June 3 8:50am Group 3 Practice 8:00am—12 noon Registration 9:10am Group 2 Practice 8:10am TA Qualifying (split) 60mins 9:30am Group 1 Practice 9:10am Group 5 Feature Race 2 9:50am Group 12 Practice 9:40am Group 3 Feature Race 2 10:10am Group 11 Practice 10:10am Group 9 Feature Race 2 10:30am Group 10 Practice 10:40am Group -

![Ferrari Daytona[Redigera | Redigera Wikitext] Hoppa Till Navigeringhoppa Till Sök Ferrari Daytona](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9123/ferrari-daytona-redigera-redigera-wikitext-hoppa-till-navigeringhoppa-till-s%C3%B6k-ferrari-daytona-1509123.webp)

Ferrari Daytona[Redigera | Redigera Wikitext] Hoppa Till Navigeringhoppa Till Sök Ferrari Daytona

Bilaga 3 Ferrari Daytona[redigera | redigera wikitext] Hoppa till navigeringHoppa till sök Ferrari Daytona Ferrari 365 GTB/4. Grundinformation Märke Ferrari Tillverkning 1968-1974 Designer Pininfarina Konstruktion Klass Sportbil Karosseri 2-d coupé 2-d roadster Besläktade Ferrari 365 Liknande Aston Martin V8 Lamborghini Jarama Maserati Ghibli Drivlina Motor 12-cyl V-motor Drivning Bakhjulsdrift Växellåda 5-växlad manuell Bränslekap. 98 l Dimensioner Hjulbas 240 cm Längd 443 cm Bredd 176 cm Höjd 125 cm Vikt 1280 kg Kronologi Föregångare Ferrari 275 Efterträdare Ferrari Berlinetta Boxer Ferrari Daytona är en sportbil, tillverkad av den italienska biltillverkaren Ferrari mellan 1968 och 1974. Bilaga 3 Innehåll • 1Bakgrund • 2Motor • 3365 GTB/4 • 4365 GTS/4 • 5Motorsport • 6Bilder • 7Källor Bakgrund[redigera | redigera wikitext] Daytonan ersatte 275 GTB/4 som företagets Berlinetta, vagnen för kunden som ville använda sin sportbil för seriös racing. Namnet Daytona användes aldrig av Ferrari själva i officiella sammanhang. Den döptes så av media för att påminna om Ferraris seger i Daytona 24- timmars 1967. Bilen byggde på tekniken från företrädaren, med individuella hjulupphängningar runt om och transaxel, det vill säga växellådamonterad bak vid differentialen. Karossen byggdes av Scaglietti och hade motorhuv, baklucka och dörrar av aluminium för att hålla nere vikten. Ferrari Daytona ansågs allmänt vara Ferraris svar på succén Lamborghini Miura, som presenterades i Genève två år tidigare. Även om Daytonan var mer konservativt byggd med frontmotor, till skillnad från Miura som hade mittmonterad motor, var den med sin toppfart runt 280 km/h och toppklassiga vägegenskaper en av världens snabbaste bilar för landsvägsbruk. Ferrari Daytona efterträddes av den mittmotormonterade Berlinetta Boxer.