The History and Future of Narragansett Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamestown Historical Society HERITAGE

Jamestown Historical Society HERITAGE FALL 2016 To collect, preserve, and share with others the heritage of Jamestown, Rhode Island. FROM THE PRESIDENT I am honored to have been elected as president of In the news- the Jamestown Historical Society, following in the letter you will footsteps of longtime Board member and former learn of all of the Board president, Rosemary Enright. Having served on great work of the JHS Board for six years and as a Museum Dianne Rugh, Professional at the International Tennis Hall of Fame, Collections I’m eager to bring my experience to support all of the Committee chair passionate and hardworking people who serve and and her dedicated execute this mission year-round. team who care for The Board is a very special group of people from our valuable and our community who work tirelessly to collect, diverse collection. preserve, and share with all of you the heritage of Thousands of Jamestown. I look forward to working with them. artifacts are stored and cataloged We say good-by to two outgoing Board members under Dianne’s this year, and I’d like to thank them for their service expert guidance and the records made accessible and dedication. Terry Lanza, as Program Committee online through our website. chair, has overseen three years of events, including very successful House Tour Preview Party fundraisers. In closing, I’d like to recognize each and every For six years Larry McDonald, our Battery Committee Board member and volunteer – those who support us chair, has worked hard to make the town’s Conanicut with membership and annual fund donations and who Battery Historic Park a beautiful place to walk, keeping attend our events such as the House Tour and the existing paths opened and encouraging prospective Windmill Day as well as those who work in the vault Eagle Scouts to build new ones. -

Historic Resources of North Kingstown, RI.Partial Inventory: Andorcommon Historic and Architectural Pronerti Es 2

_______ Esp. 10-31-94 ,i4nited States Department of the InterIor National Park Service For 14PS use only National Register of Histèiric Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name oc N.A. Historic Resources of North Kingstown, RI.Partial Inventory: andorcommon Historic and Architectural Pronerti es 2. Location street & number town boundaries of Town of Nor ngstown, RinottorbHcatlon congressional district 112 city1town North Kingstown N.A..vicinityof I-Jon. Claudine Schneider state Rhode Island code 44 county Washington code 009 1* Classification see also inventory sheets egory Ownership Status Present Use district - public occupied & agriculture -- museum SL. buildings - private A unoccupied commercial park 1L. strOcture JL both - X. work in progress - educational _ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious - object N in process yes: restricted ...... government - - sckntlflc being considered yes: unrestricted L. industrial transportation no military other:* I 4. Owner of Property name Multiple; see inventory sheets street & number city, town - vicinity of slate 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry ot deeds, etc. North Kings town Town Hall street&number 80 Boston Neck Road clty.town North Kingstown state Rhode Island 6. Representation in Existing Surveys North Kingstown, Rhode Island: see cont. sheet #1 title Statewiue Historic Preservatiorjas this property been determined eligible? - yes_____ no P.eport, W-NK-l jjoventher, 1979 -_____ _tederal .7state depositoryforsurveyrecorcis Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission clty,town Providence state Rhode Island NPS Form logoc-. 0MB Mo. 1024-0018 3-82 Exp- 0 31 84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form ;tnte Continuation sheet 1 Item numb’,. -

Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Prudence Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background Prudence Island is located in the geographic center of Narragansett Bay. The island is approximately 7 miles long and 1 mile across at its widest point. Located at the south end of the island is the Narragansett Bay Research Reserve’s Lab & Learning Center. The Center contains educational exhibits, a public meeting area, library, and research labs for staff and visiting scientists. The Reserve manages approximately 60% of Prudence; the largest components are at the north and south ends of Prudence Island. The vegetation on Prudence reflects the extensive farming that took place in the area until the early 1900s. After the fields were abandoned, woody plants gradually replaced the herbaceous species. The uplands are now covered with a dense shrub growth of bayberry, blueberry, arrowwood, and shadbush interspersed with red cedar, red maple, black cherry, pitch pine and oak. Green briar and Asiatic bittersweet cover much of the island as well. Prudence Island also supports one of the most dense white-tailed deer herds in New England . Raccoons, squirrels, Eastern red fox, Eastern cottontail rabbits, mink, and white-footed mice are plentiful. The large, salt marshes at the north end of Prudence are used as feeding areas by a number of large wading birds such as great and little blue herons, snowy and great egrets, black-crowned night herons, green-backed herons and glossy ibis. Between September and May, Prudence Island is also used as a haul-out site for harbor seals. History of Prudence Island Before colonial times, Prudence and the surrounding islands were under the control of the Narragansett Native Americans. -

Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve

Last Updated 1/20/07 Patience Island Narragansett Bay Research Reserve Background This 207-acre island lies to the west of northern Prudence Island. At their closest, the two islands are only 900 feet apart. The Patience Island is dominated by tall shrubs interspersed with red cedar and black cherry. Common shrubs include bayberry, highbush blueberry, and shadbush. Much of the island is also covered by brier, Asiatic bittersweet and poison ivy. A deciduous forest is gradually replacing the shrub habitat in some parts of the island. The small salt marsh on the southeastern shore provides habitat for seablite, a plant species common in other areas of the country, but rare in Rhode Island. The upland area of Patience Island supports a variety of wildlife including white-tailed deer, red fox, and Eastern cottontail rabbits. Coastal areas are used extensively by migrant and wintering waterfowl species such as horned grebes, greater scaup, black ducks and scoters. Quahogs are abundant in the sandy sediment. There is no ferry service available to this island. Visitors are welcome but you must provide your own transportation. Be aware that there is a high population of ticks, the trails may be overgrown, and camping is not permitted. History of Patience Island Historically, the Patience Island Farm covered an area of approximately 200 acres, nearly the entire island, and was a working farm as early as the mid-seventeenth century. The farm buildings were burned by the British during the Revolutionary War. After the war, the buildings were rebuilt and the farm remained in operation until the early twentieth century. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

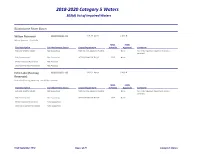

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

Jamestown, Rhode Island

Historic andArchitectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island 1 Li *fl U fl It - .-*-,. -.- - - . ---... -S - Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission 1995 Historic and Architectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island, is published by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, which is the state historic preservation office, in cooperation with the Jamestown Historical Society. Preparation of this publication has been funded in part by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions herein, however, do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. The Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission receives federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the United States Department of the Interior strictly prohibit discrimination in departmental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap. Any person who believes that he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Cover East Fern’. Photograph c. 1890. Couriecy of Janiestown Historical Society. This view, looking north along tile shore, shows the steam feriy Conanicut leaving tile slip. From left to rig/It are tile Thorndike Hotel, Gardner house, Riverside, Bay View Hotel and tile Bay Voyage Inn. Only tile Bay Voyage Iiii suivives. Title Page: Beavertail Lighthouse, 1856, Beavertail Road. Tile light/louse tower at the southern tip of the island, the tallest offive buildings at this site, is a 52-foot-high stone structure. -

City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan

Updated 1/13/10 hk Version 4.4 City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan The Newport Waterfront Commission Prepared by the Harbor Management Plan Committee (A subcommittee of the Newport Waterfront Commission) Version 1 “November 2001” -Is the original HMP as presented by the HMP Committee Version 2 “January 2003” -Is the original HMP after review by the Newport . Waterfront Commission with the inclusion of their Appendix K - Additions/Subtractions/Corrections and first CRMC Recommended Additions/Subtractions/Corrections (inclusion of App. K not 100% complete) -This copy adopted by the Newport City Council -This copy received first “Consistency” review by CRMC Version 3.0 “April 2005” -This copy is being reworked for clerical errors, discrepancies, and responses to CRMC‟s review 3.1 -Proofreading – done through page 100 (NG) - Inclusion of NWC Appendix K – completely done (NG) -Inclusion of CRMC comments at Appendix K- only “Boardwalks” not done (NG) 3.2 -Work in progress per CRMC‟s “Consistency . Determination Checklist” : From 10/03/05 meeting with K. Cute : From 12/13/05 meeting with K. Cute 3.3 -Updated Approx. J. – Hurricane Preparedness as recommend by K. Cute (HK Feb 06) 1/27/07 3.4 - Made changes from 3.3 : -Comments and suggestions from Kevin Cute -Corrects a few format errors -This version is eliminates correction notations -1 Dec 07 Hank Kniskern 3.5 -2 March 08 revisions made by Hank Kniskern and suggested Kevin Cute of CRMC. Full concurrence. -Only appendix charts and DEM water quality need update. Added Natural -

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR

CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Kenneth B. Raposa 23 An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve Figure 4.1. Geographic setting of the NBNERR, including the extent of the 4,818 km2 (1,853-square-mile) Narragan- sett Bay watershed. GIS data sources courtesy of RIGIS (www.edc.uri.edu/rigis/) and Massachusetts GIS (www.mass. gov/mgis/massgis.htm). 24 CHAPTER 4. Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Ecological Geography of the NBNERR Geographic Setting Program in 2001. Annual weather patterns on Pru- dence Island are similar to those on the mainland, Prudence Island is located roughly in at least when considering air temperature, wind the center of Narragansett Bay, R.I., bounded by speed, and barometric pressure (Figure 4.3). 41o34.71’N and 41o40.02’N, and 71o18.16’W and Using recent data collected from the 71o21.24’W. Metropolitan Providence lies 14.4 NBNERR weather station, some annual patterns kilometers (km) (9 miles) to the north and the city are clear. For example, air temperature, relative of Newport lies 6.4 km (4 miles) to the south of humidity, and the amount of photosynthetically Prudence (Fig 4.1). Because of its central location, active radiation (PAR) all clearly peak during the Prudence Island is affected by numerous water summer months (Fig. 4.3). The total amount of masses in Narragansett Bay including nutrient-rich precipitation is generally highest during spring and freshwaters fl owing downstream from the Provi- fall, but this pattern is not as strong as the former dence and Taunton rivers and oceanic tidal water parameters based on these limited data. -

Ecological Profile Ch. 3 Land Use History

CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use Joseph J. Bains and Robin L.J. Weber 15 An Ecological Profile of the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve Figure 3.1. The Prudence Inn (built in 1894) contained more than 20 guestrooms. Postcard reproduction. 16 CHAPTER 3. Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR Human and Land-Use History of the NBNERR Overview ary War. During the time that forests were being cleared, drainage of coastal and inland wetlands Prudence Island has had a long history of also occurred, which together with the deforesta- predominantly seasonal use, with a human popula- tion activities would have altered the hydrology of tion that has fl uctuated considerably due to changes the region (Niering, 1998). Changes in hydrology in the political climate. The location of Prudence would, in turn, infl uence future vegetation composi- Island near the center of Narragansett Bay, although tion. Although reforestation has occurred throughout considered isolated and relatively inaccessible by much of the region, the current forests are dissimilar today’s standards, made the island a highly desirable to the forests that existed prior to European settle- central location during periods when water travel ment, refl ected most notably in the reduction or loss was prevalent. of previously dominant or common species. In addi- The land-use practices on Prudence Island tion to forest compositional trends that can be linked are generally consistent with land-use practices to past land use, structurally the forests are most throughout New England from prehistoric periods often young and even aged (Foster, 1992). -

Prudence Island Community Wildfire Protection Plan

PRUDENCE ISLAND COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Narragansett Bay Research Reserve, Rhode Island Division of Forest Environment, Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management & Prudence Island Volunteer Fire Department Page 1 of 49 April 2018 PRUDENCE ISLAND COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTON PLAN Guidance Committee Olney Knight Robin Weber Kevin Blount Rhode Island DEM Narragansett Bay NERR Prudence Island Fire Department Division of Forest Environment Stewardship Coordinator Officer Forest Fire Program Coordinator Prepared By Alex Entrup, Senior Specialist and Joel R. Carlson, Principal Consultant Funding for this project was provided in part through the Rhode Island Division of Forest Environment Forest Fire Program, Department of Environmental Management, in cooperation with the USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to: USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410; 800-795-3272 (voice) or 202-720-6382(TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Page 2 of 49 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION/EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................... 4 COMMUNITY BACKGROUND ............................................................................ -

Draft Chapter

Ocean Special Area Management Plan Chapter 4: Cultural and Historic Resources Table of Contents 400 Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 410 Historic Contexts and Cultural Landscapes of the Ocean SAMP Area .......................4 410.1 Pre-Contact Geological History............................................................................5 410.2 Narragansett Tribal History.................................................................................6 410.3 European Exploration and Colonial Settlement Landscape Context .............16 410.4 Post-Colonial Cultural Landscape Context.......................................................18 410.5 Military Landscape Context ...............................................................................21 410.6 Fisheries Landscape Context ..............................................................................31 410.6.1 Rhode Island Fisheries.............................................................................31 410.6.2 Fishing and Subsistence on Block Island.................................................33 410.6.3 Historic Shipwrecks of Fishing Vessels ..................................................34 410.6.4 Historic Harbor Features..........................................................................35 410.7 Marine Transportation and Commercial Landscape Context ........................35 410.8 Recreation and Tourism Landscape Context....................................................38