Flying the Southeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11Th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia

11th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia 11th Australian Space Forum a 11th Australian Space Forum Wednesday 31 March 2021 Adelaide, South Australia Major Sponsor Supported by b 11th Australian Space Forum c Contents Welcome from the Chair of The Andy Thomas Space Foundation The Andy Thomas Space Foundation is delighted to welcome you to the 11th Australian Space Forum. Contents 11th Australian Space Forum The Foundation will be working with partners Wednesday 31 March 2021 1 Welcome and sponsors, including the Australian Space Adelaide, South Australia — Chair of The Andy Thomas Agency, on an ambitious agenda of projects Space Foundation to advance space education and outreach. Adelaide Convention Centre, — Premier of South Australia We are reaching out to friends and supporters North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia — Head of the Australian who have a shared belief in the power of Forum sessions: Hall C Space Agency education, the pursuit of excellence and a Exhibition: Hall H commitment to diversity and inclusion. We 6 Message from the CEO The Foundation was established in 2020 for look forward to conversations during the 8 Forum Schedule the purpose of advancing space education, Forum – as well as ongoing interaction - about raising space awareness and contributing our shared interests and topics of importance 11 Speaker Profiles to the national space community. We to the national space community. are delighted that the South Australian 28 Company Profiles We hope you enjoy the 11th Australian Government has entrusted us with the future Space Forum. 75 Foundation Corporate Sponsors conduct of the Australian Space Forum – and Professional Partners Australia’s most significant space industry Michael Davis AO meeting – and we intend to ensure that the Chair, Andy Thomas Space Foundation 76 Venue Map Forum continues to be the leading national 77 Exhibition Floorplan platform for the highest quality information and discussion about space industry topics. -

Analysis of a Southerly Buster Event and Associated Solitary Waves

CSIRO PUBLISHING Journal of Southern Hemisphere Earth Systems Science, 2019, 69, 205–215 https://doi.org/10.1071/ES19015 Analysis of a southerly buster event and associated solitary waves Shuang WangA,B,D, Lance LeslieA, Tapan RaiA, Milton SpeerA and Yuriy KuleshovC AUniversity of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia. BBureau of Meteorology, PO Box 413, Darlinghurst, NSW 1300, Australia. CBureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. This paper is a detailed case study of the southerly buster of 6–7 October 2015, along the New South Wales coast. It takes advantage of recently available Himawari-8 high temporal- and spatial-resolution satellite data, and other observational data. The data analyses support the widespread view that the southerly buster is a density current, coastally trapped by the Great Dividing Range. In addition, it appeared that solitary waves developed in this event because the prefrontal boundary layer was shallow and stable. A simplified density current model produced speeds matching well with observational southerly buster data, at both Nowra and Sydney airports. Extending the density current theory, to include inertia-gravity effects, suggested that the solitary waves travel at a speed of ,20% faster than the density current. This speed difference was consistent with the high-resolution satellite data, which shows the solitary waves moving increasingly ahead of the leading edge of the density current. Additional keywords: coastally trapped disturbance, density currents. Received 19 May 2019, accepted 7 October 2019, published online 11 June 2020 1 Introduction speed of ,20 m/s at the leading edge of the ridge (Holland and Southerly busters (SBs) occur during the spring and summer Leslie 1986). -

The Bubbly Professor Tackles Topography

The Bubbly Professor Tackles Topography France Land: Western Alps, Massif Central, Vosges Mountains, Pyrenees, Auvergne Mountains, Jura Mountains, Morvan Massif, Mont Blanc Water: Rhône River, Moselle River, Rhine River, Loire River, Cher River, Charente River, Garonne River, Dordogne River, Gironde River (Estuary), Seine River, Marne River, Hérault River, Saône River, Aube River, Atlantic Ocean, Bay of Biscay, Mediterranean Sea, English Channel Wind: Gulf Stream, Mistral, Tramontane Italy Land: Italian Alps, Apennines, Dolomites, Mount Etna, Mount Vesuvius, Mont Blanc Water: Arno River, Po River, Tiber River, Tanaro River, Adige River, Piave River, Tagliamento River, Sesia River, Lake Garda, Lake Como, Mediterranean Sea, Gulf of Venice Wind: Sirocco winds, Grecale Winds Spain: Land: Pyrenees, Meseta Central, Picos de Europa, Sierra Nevada, Cantabrian Mountains, Sistema Ibérico, Montes de Toledo, Sierra de Gredos, Sierra de Guadaramma, Sistema Penibértico, Canary Islands, Balearic Islands Water: Ebro River, Duero River, Tagus River, Guadiana River, Guadalquivir River, Rías Baixas, Rías Altas, Atlantic Ocean, Bay of Biscay, Gulf of Cadiz, Mediterranean Sea Wind: Garbinada Winds, Cierzo Winds, Levante, Poniente Portugal Land: Serra da Estrela, Montes de Toledo, Sintra Mountain, Azores, Madeira Island Water: Minho River, Douro River, Tagus (Tejo) River, Guadiana River, Sado River, Mondego River, Ave River, Gulf of Cadiz, Atlantic Ocean Winds: Portugal Current Austria Land: Central Alps, Pannonian Basin, Bohemian Forest Water: Danube River, -

Temporal and Spatial Study of Thunderstorm Rainfall in the Greater Sydney Region Ali Akbar Rasuly University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1996 Temporal and spatial study of thunderstorm rainfall in the Greater Sydney region Ali Akbar Rasuly University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rasuly, Ali Akbar, Temporal and spatial study of thunderstorm rainfall in the Greater Sydney region, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Geosciences, University of Wollongong, 1996. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1986 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL STUDY OF THUNDERSTORM RAINFALL IN THE GREATER SYDNEY REGION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree UNIVERSITY O* DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ALIAKBAR RASULY B.Sc. & M.Sc. (IRAN, TABRIZ University) SCHOOL OF GEOSCIENCES 1996 CERTIFICATION The work presented herein has not been submitted to any other university or institution for a higher degree and, unless acknowledged, is my own original work. A. A. Rasuly February 1996 i ABSTRACT Thunderstorm rainfall is considered as a very vital climatic factor because of its significant effects and often disastrous consequences upon people and the natural environment in the Greater Sydney Region. Thus, this study investigates the following aspects of thunderstorm rainfall climatology of the region between 1960 to 1993. In detail, it was found that thunderstorm rainfalls in Sydney have marked diurnal and seasonal variations. They are most frequent in the spring and summer and during the late afternoon and early evening. Thunderstorms occur primarily over the coastal areas and mountains, and less frequently over the lowland interior of the Sydney basin. -

JSHESS Early Online View

DOI: 10.22499/3.6901.015 JSHESS early online view This article has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Southern Hemisphere Earth Systems Science and undergone full peer review. It has not been through the copy-editing, typesetting and pagination, which may lead to differences between this version and the final version. Corresponding author: Shuan g Wang, Bureau of Meteorology, Sydney Email: [email protected] 1 2 Analysis of a Southerly Buster Event and 3 Associated Solitary Waves 4 5 Shuang Wang1, 2, Lance Leslie1, Tapan Rai1, Milton Speer1 and Yuriy 6 Kuleshov3 7 1 University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia 8 2 Bureau of Meteorology, Sydney, Australia 9 3 Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia 10 11 (Manuscript submitted March 19, 2019) 12 Revised version submitted July 23, 2019 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Corresponding author: Shuan g Wang, Bureau of Meteorology, Sydney Email: [email protected] 29 30 ABSTRACT 31 This paper is a detailed case study of the southerly buster of October 6-7, 2015, along the New 32 South Wales coast. It takes advantage of recently available Himawari-8 high temporal- and spatial- 33 resolution satellite data, and other observational data. The data analyses support the widespread 34 view that the southerly buster is a density current, coastally trapped by the Great Dividing Range. 35 In addition, it appears that solitary waves develop in this event because the prefrontal boundary 36 layer is shallow and stable. A simplified density current model produced speeds matching well 37 with observational southerly buster data, at both Nowra and Sydney airports. -

Cold Air Incursions Over Subtropical and Tropical South America: a Numerical Case Study

DECEMBER 1999 GARREAUD 2823 Cold Air Incursions over Subtropical and Tropical South America: A Numerical Case Study RENEÂ D. GARREAUD Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (Manuscript received 6 June 1998, in ®nal form 24 November 1998) ABSTRACT Synoptic-scale incursions of cold, midlatitude air that penetrate deep into the Tropics are frequently observed to the east of the Andes cordillera. These incursions are a distinctive year-round feature of the synoptic climatology of this part of South America and exhibit similar characteristics to cold surges observed in the lee of the Rocky Mountains and the Himalayan Plateau. While their large-scale structure has received some attention, details of their mesoscale structural evolution and underlying dynamics are largely unknown. This paper advances our understanding in these matters on the basis of a mesoscale numerical simulation and analysis of the available data during a typical case that occurred in May of 1993. The large-scale environment in which the cold air incursion occurred was characterized by a developing midlatitude wave in the middle and upper troposphere, with a ridge immediately to the west of the Andes and a downstream trough over eastern South America. At the surface, a migratory cold anticyclone over the southern plains of the continent and a deepening cyclone centered over the southwestern Atlantic grew mainly due to upper-level vorticity advection. The surface anticyclone was also supported by midtropospheric subsidence on the poleward side of a jet entrance±con¯uent ¯ow region over subtropical South America. The northern edge of the anticyclone followed an anticyclonic path along the lee side of the Andes, reaching tropical latitudes 2± 3 days after its onset over southern Argentina. -

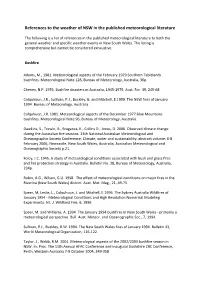

References to the Weather of NSW in the Published Meteorological Literature

References to the weather of NSW in the published meteorological literature The following is a list of references in the published meteorological literature to both the general weather and specific weather events in New South Wales. The listing is comprehensive but cannot be considered exhaustive. Bushfire Adams, M., 1981. Meteorological aspects of the February 1979 Southern Tablelands bushfires. Meteorological Note 126, Bureau of Meteorology, Australia, 36p. Cheney, N.P. 1976. Bushfire disasters in Australia, 1945-1975. Aust. For. 39, 245-68 Colquhoun, J.R., Sullivan, P.J., Buckley, B. and Mitchell, E.1999. The NSW fires of January 1994. Bureau of Meteorology, Australia. Colquhuon, J.R. 1981. Meteorological aspects of the December 1977 Blue Mountains bushfires. Meteorological Note 96, Bureau of Meteorology, Australia. Dawkins, S., Trewin, B., Braganza, K., Collins D., Jones, D. 2006. Observed climate change during the Australian fire seasons. 13th National Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society Conference: Climate, water and sustainability: abstract volume: 6-8 February 2006, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia, Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society p.21. Foley, J.C. 1945. A study of meteorological conditions associated with bush and grass fires and fire protection strategy in Australia. Bulletin No. 38, Bureau of Meteorology, Australia, 234p. Robin, A.G., Wilson, G.U. 1958. The effect of meteorological conditions on major fires in the Riverina (New South Wales) district. Aust. Met. Mag., 21, 49-75 Speer, M, Leslie, L., Colquhoun, J. and Mitchell, E.1996. The Sydney Australia Wildfires of January 1994 - Meteorological Conditions and High Resolution Numerical Modeling Experiments. Int. J. Wildland Fire, 6, 1996 Speer, M. -

Southerly Buster Events in New Zealand

Weather and Climate (1990) 10: 35-54 35 SOUTHERLY BUSTER EVENTS IN NEW ZEALAND R. N. Ridley' New Zealand Meteorological Service, Wellington, New Zealand ABSTRACT The 'southerly buster' is a particularly intense form of southerly change which occurs along the New South Wales coast of Australia. In this study similar changes occurring in late summer in eastern New Zealand are identified and described, with emphasis on their synoptic environment. Typical features found include a sharp or sharpening trough approaching in a strong westerly flow, much warmer than usual air over New Zealand preceding the change, a shallow southerly flow following the change, and a complex meso-scale signature at the surface. The synoptic scale flow is found to have a significant influence on the formation and nature of the changes. On the meso- scale, the New Zealand southerly buster appears to have unsteady gravity current-like features similar to its Australian counterpart. A typical scenario for the occurrence of a southerly buster along the east coast of New Zealand is given. INTRODUCTION tries as marine, aviation, construction, forest- The Southern Alps are a major barrier to ry (including fire-fighting) and power supply. the prevailing westerly flow, occupying up to They pose a difficult forecasting problem due a third of the depth of the troposphere, and the to their occurrence on time and space scales structure of any front is expected, therefore, that are not well resolved by current numeri- to be greatly modified by flow over or around cal prediction models, and a lack of under- the mountains. Indeed, it is well known by standing of their dynamics. -

Brickfielders and Bursters

grandfather’s rain-making ritual faithfully Lambert, J (ed), 1996. Macquarie book of recounted by an old bushman in the slang: Australian slang in the 1990s, “Aboriginalities” section of the Bulletin (Huie, Macquarie Library, Macquarie University, 2011). NSW, 276pp. By the early twentieth century, Australians Ludowyx, William, 1999. Send Her Down spoke of Hughie as if he were a knockabout Who-ie? Ozwords, available from god – an equal, a mate. But that’s not how he www.anu.edu.au/andc/pubs/ozwords/ began. In the 1880s, the thirsty stockmen of October_99/index.html. Narrandera were not appealing for divine Murray, F, 2011. Thomas O’Shaughnessey’s intervention when they appealed to Hughie. diary, entry for 1848 – The Early Pioneers and They were recalling a local man’s audacity. their lives. Available from They were saluting John Ziegler Huie and his www.frankmurray.com.au/?page_id=420. meteorological cannon. Reilly, P.J., 1853. Notes to James Allen in References Journal of an experimental trip by the “Lady Huie, J., 2011. Huie Family Tree. Available Augusta” on the River Murray. Australiana from think.io/pub/Mirror/www.futureweb.com. facsimile editions 202, Ferguson no. 5897, au/johnhuie/tree.htm. 81–2. Brickfielders and Bursters Neville Nicholls School of Geography & Environmental Science, Monash University, Melbourne Address for correspondence: [email protected] The Australian Meteorological & So, when did “brickfielder” start to be used to Oceanographic Society (AMOS) has been denote a hot, northerly wind? And why? running a competition to name Melbourne’s Where was it used in this way? And what hot northerly wind, and the winners have just happened to the term? been announced (see News in this issue). -

Writing the Illawarra

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2001 Once upon a place: writing the Illawarra Peter Knox University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Knox, Peter, Once upon a place: writing the Illawarra, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2001. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2242 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

Atmospheric Density Currents: Impacts on Aviation Over Nsw and Act

ATMOSPHERIC DENSITY CURRENTS: IMPACTS ON AVIATION OVER NSW AND ACT [Shuang Wang] [Master of Science and Master of Engineering] [Supervisors: Tapan Rai, Lance Leslie, Yuriy Kuleshov] Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Mathematical and Physical Science University of Technology Sydney [2019] Atmospheric Density Currents: Impacts on Aviation over NSW and ACT i Statement of Original Authorship Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. ii Atmospheric Density Currents: Impacts on Aviation over NSW and ACT Keywords ACT, Aviation, Canberra, climate, cooler, damaging winds, density current, down burst, microburst, NSW, observations, permutation testing, ranges, Rossby waves, satellite images, sort-lived gusty winds, southerly busters, squall lines, Sydney, thunderstorms, turbulence, warnings, wavelet analysis, wind shear (in alphabetical order) Atmospheric Density Currents: Impacts on Aviation over NSW and ACT iii Abstract Three main types of density currents (DCs) which have significant impacts for aviation are investigated in detail over New South Wales (NSW) state of Australia and Australian capital Territory (ACT) in the research. The three types of density currents are southerly busters (SBs) along the coastal NSW, thunderstorm downbursts over north-western NSW and easterly DCs over Canberra. The research take advantage of the recently available Himawari-8 high temporal- and spatial- resolution satellite data, Sydney wind profiler data, Doppler radar data, radiosonde data, half hourly METAR and SPECI aviation from observation data Bureau of Meteorology Climate zone, synoptic weather charts and other observational data. In addition, simply model for density currents, global data assimilation system (GDAS) meteorological model outputs, and the Australian Community Climate and Earth-System Simulator (ACCESS) operational model products are employed in the research. -

Marine Meteorology

PUBLICATIONS VISION DIGITAL ONLINE MAR046 MARITIME STUDIES Supplementary Notes MARINE METEOROLOGY Fifth Edition www.westone.wa.gov.au MARINE METEOROLOGY Supplementary Notes Fifth Edition Larry Lawrence This edition updated by Kenn Batt Copyright and Terms of Use © Department of Training and Workforce Development 2016 (unless indicated otherwise, for example ‘Excluded Material’). The copyright material published in this product is subject to the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and is owned by the Department of Training and Workforce Development or, where indicated, by a party other than the Department of Training and Workforce Development. The Department of Training and Workforce Development supports and encourages use of its material for all legitimate purposes. Copyright material available on this website is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license unless indicated otherwise (Excluded Material). Except in relation to Excluded Material this license allows you to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially provided you attribute the Department of Training and Workforce Development as the source of the copyright material. The Department of Training and Workforce Development requests attribution as: © Department of Training and Workforce Development (year of publication). Excluded Material not available under a Creative Commons license: 1. The Department of Training and Workforce Development logo, other logos and trademark protected material; and 2. Material owned by third parties that has been reproduced with permission. Permission will need to be obtained from third parties to re-use their material. Excluded Material may not be licensed under a CC BY license and can only be used in accordance with the specific terms of use attached to that material or where permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).