Livy's Cossus and Augustus, Tacitus' Germanicus and Tiberius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

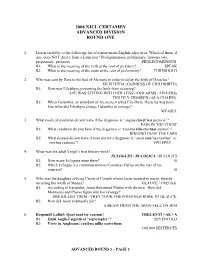

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Histoire Romaine

HISTOIRE ROMAINE EUGÈNE TALBOT PARIS - 1875 AVANT-PROPOS PREMIÈRE PARTIE. — ROYAUTÉ CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. SECONDE PARTIE. — RÉPUBLIQUE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. - CHAPITRE IV. - CHAPITRE V. - CHAPITRE VI. - CHAPITRE VII. - CHAPITRE VIII. - CHAPITRE IX. - CHAPITRE X. - CHAPITRE XI. - CHAPITRE XII. - CHAPITRE XIII. - CHAPITRE XIV. - CHAPITRE XV. - CHAPITRE XVI. - CHAPITRE XVII. - CHAPITRE XVIII. - CHAPITRE XIX. - CHAPITRE XX. - CHAPITRE XXI. - CHAPITRE XXII. TROISIÈME PARTIE. — EMPIRE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. AVANT-PROPOS. LES découvertes récentes de l’ethnographie, de la philologie et de l’épigraphie, la multiplicité des explorations dans les diverses contrées du monde connu des anciens, la facilité des rapprochements entre les mœurs antiques et les habitudes actuelles des peuples qui ont joué un rôle dans le draine du passé, ont singulièrement modifié la physionomie de l’histoire. Aussi une révolution, analogue à celle que les recherches et les œuvres d’Augustin Thierry ont accomplie pour l’histoire de France, a-t-elle fait considérer sous un jour nouveau l’histoire de Rome et des peuples soumis à son empire. L’officiel et le convenu font place au réel, au vrai. Vico, Beaufort, Niebuhr, Savigny, Mommsen ont inauguré ou pratiqué un système que Michelet, Duruy, Quinet, Daubas, J.-J. Ampère et les historiens actuels de Rome ont rendu classique et populaire. Nous ne voulons pas dire qu’il ne faut pas recourir aux sources. On ne connaît l’histoire romaine que lorsqu’on a lu et étudié Salluste, César, Cicéron, Tite-Live, Florus, Justin, Velleius, Suétone, Tacite, Valère Maxime, Cornelius Nepos, Polybe, Plutarque, Denys d’Halicarnasse, Dion Cassius, Appien, Aurelius Victor, Eutrope, Hérodien, Ammien Marcellin, Julien ; et alors, quand on aborde, parmi les modernes, outre ceux que nous avons nommés, Machiavel, Bossuet, Saint- Évremond, Montesquieu, Herder, on comprend l’idée, que les Romains ont développée dans l’évolution que l’humanité a faite, en subissant leur influence et leur domination. -

The Roman Army's Emergence from Its Italian Origins

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE ROMAN ARMY’S EMERGENCE FROM ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Richard Talbert Nathan Rosenstein Daniel Gargola Fred Naiden Wayne Lee ABSTRACT PATRICK ALAN KENT: The Roman Army’s Emergence from its Italian Origins (Under the direction of Prof. Richard Talbert) Roman armies in the 4 th century and earlier resembled other Italian armies of the day. By using what limited sources are available concerning early Italian warfare, it is possible to reinterpret the history of the Republic through the changing relationship of the Romans and their Italian allies. An important aspect of early Italian warfare was military cooperation, facilitated by overlapping bonds of formal and informal relationships between communities and individuals. However, there was little in the way of organized allied contingents. Over the 3 rd century and culminating in the Second Punic War, the Romans organized their Italian allies into large conglomerate units that were placed under Roman officers. At the same time, the Romans generally took more direct control of the military resources of their allies as idea of military obligation developed. The integration and subordination of the Italians under increasing Roman domination fundamentally altered their relationships. In the 2 nd century the result was a growing feeling of discontent among the Italians with their position. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee. -

Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay

% nvy tkvr /S^lU, CsUdx *TV IrrTCV* U- tv/ <n\V ftjw ^ Jl— i$fO-$[ . To live ^ Iz^l.cL' dcn^LU *~d |V^ ^ <X ^ ’ tri^ v^X H c /f/- v »»<,<, 4r . N^P’iTH^JJs y*^ ** 'Hvx ^ / v^r COLLECTION OF BRITISH AUTHORS. VOL. CXCVIII. LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME BY THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. IN ONE VOLUME. TATJCHNITZ EDITION". By the same Author, THE HISTORY OF ENGLAND.10 vols. CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL ESSAYS.5 vols. SPEECHES .2 vols. BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS.1 vol. WILLIAM PITT, ATTERBURY.1 VOl. THE LIFE AND LETTERS OF LORD MACAULAY. By his Nephew GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P.4 vols. SELECTIONS FROM THE WRITINGS OF LORD MACAULAY. Edited by GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P. * . 2 vols. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/laysofancientrom00maca_3 LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME: WITH IVEY” AND “THE AEMADA” THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. COPYRIGHT EDITION, LEIPZIG BERNHARD TAUCIINITZ 1851. CONTENTS. Page PREFACE . i HORATIUS.35 THE BATTLE OF THE LAKE REGILLUS.81 VIRGINIA.143 THE PROPHECY OF CAPYS.189 IVRY: A SONG OF THE HUGUENOTS ..... 221 THE ARMADA: A FRAGMENT.231 4 PREFACE. That what is called the history of the Kings and early Consuls of Rome is to a great extent fabulous, few scholars have, since the time of Beaufort, ven¬ tured to deny. It is certain that, more than three hundred and sixty years after the date ordinarily assigned for the foundation of the city, the public records were, with scarcely an exception, destroyed by the Gauls. It is certain that the oldest annals of the commonwealth were compiled more than a cen¬ tury and a half after this destruction of the records. -

A Római Nép Története a Város Alapításától 2

TITUS LIVIUS A RÓMAI NÉP TÖRTÉNETE A VÁROS ALAPÍTÁSÁTÓL FORDÍTOTTA ÉS A JEGYZETANYAGOT ÖSSZEÁLLÍTOTTA MURAKÖZY GYULA ÖTÖDIK KÖNYV HATODIK KÖNYV HETEDIK KÖNYV NYOLCADIK KÖNYV KILENCEDIK KÖNYV TIZEDIK KÖNYV NÉVMUTATÓ MÁSODIK KÖTET 2 ÖTÖDIK KÖNYV 1. Mindenütt béke volt már megint, csak a rómaiak és a veiibeliek álltak harcra készen, olyan indulattal és gyűlölettel eltelve, hogy a legyőzöttre nyilvánvaló pusztulás várt. A két nép választási gyűlései nagyon eltérő módon zajlottak le. A rómaiak a consuli jogkörrel felruházott katonai tribunusok számát - most először - nyolcra emelték, és a következőket választották meg: M. Aemilius Mamercust (másodszor), L. Valerius Potitust (harmadszor), Ap. Claudius Crassust, M. Quinctilius Varust, L. Iulius Iulust, M. Postumiust, M. Furius Camillust és M. Postumius Albinust. A veiibeliek viszont, megelégelve az évenként megújuló s nemegyszer viszálykodást okozó választási küzdelmet, királyt választottak. Ez sértette Etruria népeit, amelyek egyaránt gyűlölték a királyságot és személy szerint a királyt is, aki hatalmaskodásával és gőgjével már korábban is terhére volt a lakosságnak. Az ünnepi játé- kokat ugyanis, amelyeknek megzavarása szentségtörésszámba ment, durván félbeszakította, mert a tizenkét nép mást választott meg helyette főpapnak. S feldühödve a mellőzésen, mikor már javában folytak a játékok, váratlanul visszarendelte a szereplőket, akik nagyrészt az ő rabszolgái voltak. Ezért a népek, amelyek mindennél jobban tisztelték a vallási szertartásokat, minthogy ezek ápolásában tűntek ki leginkább, elhatározták, -

© Copyright 2014 Morgan E. Palmer

© Copyright 2014 Morgan E. Palmer Inscribing Augustan Personae: Epigraphic Conventions and Memory Across Genres Morgan E. Palmer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Alain M. Gowing, Chair Catherine M. Connors Stephen E. Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics University of Washington Abstract Inscribing Augustan Personae: Epigraphic Conventions and Memory Across Genres Morgan E. Palmer Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Alain M. Gowing Department of Classics This dissertation investigates the ways in which authors writing during the reign of the emperor Augustus, a period of increased epigraphic activity, appropriate epigraphic conventions in their work. Livy, Ovid, and Virgil furnish case studies to explore the ways in which Augustan authors create epigraphic intertexts that call upon readers to remember and synthesize literary and epigraphic sources. Investigation of Livy is foundational to my discussion of Ovid and Virgil because his selective treatment of epigraphic sources illustrates how inscriptions can be both authoritative and subjective. Augustan poets exploit the authority and subjectivity of inscriptions in accordance with their own authorial purposes and the genres in which they write, appropriating epigraphic conventions in ways that are both traditional and innovative. This blending of tradition and innovation parallels how the emperor himself used inscriptions to shape and control -

Livy, the History of Rome, Book I, Chapters 9-13

This ancient account of the abduction of the Sabine women comes from the Roman historian Livy who wrote around the turn of the 1st Century during the Augustan Era. This translation is by Rev. Canon Roberts and is available at www.perseus.tufts.edu. LIVY, THE HISTORY OF ROME, BOOK I, CHAPTERS 9-13 CHAPTER 9 THE RAPE OF THE SABINES The Roman State had now become so strong that it was a match for any of its neighbors in war, but its greatness threatened to last for only one generation, since through the absence of women there was no hope of offspring, and there was no right of intermarriage with their neighbors. Acting on the advice of the senate, Romulus sent envoys amongst the surrounding nations to ask for alliance and the right of intermarriage on behalf of his new community. It was represented that cities, like everything else, sprung from the humblest beginnings, and those who were helped on by their own courage and the favor of heaven won for themselves great power and great renown. As to the origin of Rome, it was well known that whilst it had received divine assistance, courage and self-reliance were not wanting. There should, therefore, be no reluctance for men to mingle their blood with their fellow men. Nowhere did the envoys meet with a favorable reception. Whilst their proposals were treated with contumely, there was at the same time a general feeling of alarm at the power so rapidly growing in their midst. Usually they were dismissed with the question, `whether they had opened an asylum for women, for nothing short of that would secure for them inter-marriage on equal terms.' The Roman youth could ill brook such insults, and matters began to look like an appeal to force. -

Livy's Republic: Reconciling Republic and Princeps in <Em>Ab Urbe Condita</Em>

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2017-12-01 Livy's Republic: Reconciling Republic and Princeps in Ab Urbe Condita Joshua Stewart MacKay Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation MacKay, Joshua Stewart, "Livy's Republic: Reconciling Republic and Princeps in Ab Urbe Condita" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 6668. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Livy's Republic: Reconciling Republic and Princeps in Ab Urbe Condita Joshua Stewart MacKay A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Roger T. Macfarlane, Chair Cecilia M. Peek Michael F. Pope Department of Comparative Arts and Letters Brigham Young University Copyright © 2017 Joshua Stewart MacKay All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Livy's Republic: Reconciling Republic and Princeps in Ab Urbe Condita Joshua Stewart MacKay Department of Comparative Arts and Letters, BYU Master of Arts As early as Tacitus, Livian scholarship has struggled to resolve the "Livian paradox," the conflict between Livy's support of the Roman Republic and his overt approval of Augustus, who brought about the end of the Republic. This paper addresses the paradox by attempting to place Livy's writings within their proper historical and literary context. -

Livy and the Spolia Opima [email protected] 9/15/2010

Kolb Ettenger Livy and the Spolia Opima [email protected] 9/15/2010 A. Religious and Cultural Significance of the Spolia Opima ‘Iuppiter Feretri’ inquit, ‘haec tibi victor Romulus rex regia arma fero, templumque his regionibus quas modo animo metatus sum dedico, sedem opimis spoliis quae regibus ducibusque hostium caesis me auctorem sequentes posteri ferent.’ Haec templi est origo quod primum omnium Romae sacratum est. (Livy 1.10.6) “’Jupiter Feretrius,’ he said, ‘I, king Romulus, the victor, bring these regal arms to you, and I, in those places which I have drawn out with my mind, dedicate a temple, a home for the spolia opima which posterity, following me as the founder, will bring after kings and leaders have been slain.’ This was the origin of the temple which of all was consecrated first in Rome.” B. The Cult of Jupiter Feretrius Feretrum – the cart for the spoils Ferre –bearing of pacem, spolia Ferire – striking of foedus C. The Evolution of the Dedication Ceremony Aulus Cornelius Cossus Marcus Claudius Marcellus Marcus Licinius Crassus? D. Cossus Slays Tolumnius and Dedicates the Spolia Opima Erat tum inter equites tribunus militum A. Cornelius Cossus. (Livy 4.19.1) “Aulus Cornelius Cossus was military tribune then among the cavalry.” Omnibus locis re bene gesta, dictator senatus consulto iussuque populi triumphans in urbem rediit. Longe maximum triumphi spectaculum fuit Cossus, spolia opima regis interfecti gerens; in eum milites carmina incondita aequantes eum Romulo canere. Spolia in aede Iouis Feretri prope Romuli spolia quae, prima opima appellata, sola ea tempestate erant, cum sollemni dedicatione dono fixit.