Online Library of Liberty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 12. Évf. 1. Sz. (1911.)

A KÉT MOESIA LEGIOEMLÉKEINEK JELENTŐSÉGE ALSÓ-PANNONIA HADTÖRTÉNETÉBEN. A marcomann háborúk daciai vonatkozásaival foglalkozva, akaratlanul is ki kellene terjeszkednünk azokra a leletekre, melyek Alsó-Pannonia területén a két Moesia légióival megannyi kérdőjelként sorakoznak elénk s melyeknek értelmezése csakis Dacia rokon leleteivel kapcsolatosan kisérthető meg. Mielőtt tehát a bonyolultabbnak mutatkozó daciai emlékcsoport had- történeti magyarázatába fognánk, lássuk először is: liogy mikor s minő rendeltetéssel kerülhettek a Közép-Duna mellé a két Moesia helyőrségébe tartozó légiók eme képviselői ? A közfelfogás szerint a Krisztus után 106-ban kitört és tíz esztendőn keresztül szörnyűséges nyomort, pusztulást támasztó marcomann háborúk katonai mozgalmaival hozza nagy általános- ságban kapcsolatba ezeket a legioemlékeket, a nélkül azonban, hogy az időpontra nézve közelebbi meghatározásokkal rendel- keznénk. A marcomann háborúk kitörését pedig általában a parthusok ellen L. Verus társcsászár személyes vezénylete alatt részben a dunamelléki helyőrségből összeállított haderővel foly- tatott háború egyenes következményeinek minősíti a történet- írás. Történeti igazság például : hogy a mi Dunántúlunk hason- felét s a Kzerémséget magában egyesítő Alsó-Pannonia egyetlen légiója: a legio II adiutrix (II. segédlegio) is 104-ben a par- thusi expeditióba vonult, a mint a leg. YI. Ferratától áthelye- zett Antistius Adventus pályafutásából megtudhatjuk. [Leg(ato) Aug(usti) leg(ionis) VI. Ferrata et secunclae adiutvicis trans- lato in eam expeditione Farthica.J A parancsnok fényes kitün- tetésekkel tért a háborúból vissza. (Qua donatus est donis mili- taribus coronis merali, valiari aurea histis paris tribus, vexillis duobus. Aranykorona vár- és sánczvívásért s három dárdával, két zászlóval diszitetett hadi érem.)1 (L. 201. 1. ábráját.) Könnyű elgondolni a határvédelem gyarlóságát, a mikor a Yácztól Zimonyig terjedő hosszú Duna-vonal a háttérbeli nagy vidékkel együtt rendes legiobeli csapatok helyett a hűségre, ki- próbáltságra össze sem hasonlítható segédcsapatokra jutott. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

“At the Sight of the City Utterly Perishing Amidst the Flames Scipio Burst Into

Aurelii are one of the three major Human subgroups within western Eramus, and the founders of the mighty (some say “Eternal”) “At the sight of the city utterly perishing Aurelian Empire. They are a sturdy, amidst the flames Scipio burst into tears, conservative group, prone to religious fervor and stood long reflecting on the inevitable and philosophical revelry in equal measure. change which awaits cities, nations, and Adding to this a taste for conquest, and is it dynasties, one and all, as it does every one any wonder the Aurelii spread their of us men. This, he thought, had befallen influence, like a mighty eagle spreading its Ilium, once a powerful city, and the once wings, across the known world? mighty empires of the Assyrians, Medes, Persians, and that of Macedonia lately so splendid. And unintentionally or purposely he quoted---the words perhaps escaping him Aurelii stand a head shorter than most unconsciously--- other humans, but their tightly packed "The day shall be when holy Troy shall forms hold enough muscle for a man twice fall their height. Their physical endurance is And Priam, lord of spears, and Priam's legendary amongst human and elf alike. folk." Only the Brutum are said to be hardier, And on my asking him boldly (for I had and even then most would place money on been his tutor) what he meant by these the immovable Aurelian. words, he did not name Rome distinctly, but Skin color among the Aurelii is quite was evidently fearing for her, from this sight fluid, running from pale to various shades of the mutability of human affairs. -

Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley

A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Publius Horatius Cocles was an officer in the Roman Army who famously defended the only bridge into Rome against an attack by Lars Porsena and King Tarquin, as recounted in Plutarch’s Life of Publicola. There is a very famous poem about this event called “Horatius at the Bridge” by Thomas Babington Macauley. It was published in Macauley’s book Lays of Ancient Rome in 1842. HORATIUS AT THE BRIDGE By Thomas Babington Macauley I LARS Porsena of Clusium By the Nine Gods he swore That the great house of Tarquin Should suffer wrong no more. By the Nine Gods he swore it, And named a trysting day, And bade his messengers ride forth, East and west and south and north, To summon his array. II East and west and south and north The messengers ride fast, And tower and town and cottage Have heard the trumpet’s blast. Shame on the false Etruscan Who lingers in his home, When Porsena of Clusium Is on the march for Rome. III The horsemen and the footmen Are pouring in amain From many a stately market-place; From many a fruitful plain; From many a lonely hamlet, Which, hid by beech and pine, 1 www.cmplenary.com A Charlotte Mason Plenary Guide - Resource for Plutarch’s Life of Publicola Like an eagle’s nest, hangs on the crest Of purple Apennine; IV From lordly Volaterae, Where scowls the far-famed hold Piled by the hands of giants For godlike kings of old; From seagirt Populonia, Whose sentinels descry Sardinia’s snowy mountain-tops Fringing the southern sky; V From the proud mart of Pisae, Queen of the western waves, Where ride Massilia’s triremes Heavy with fair-haired slaves; From where sweet Clanis wanders Through corn and vines and flowers; From where Cortona lifts to heaven Her diadem of towers. -

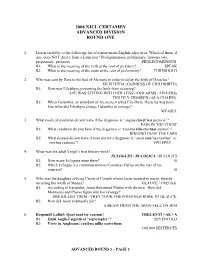

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

Quaestiones Onomatologae

929.4 N397q Digitized by tlie Internet Arcliive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/quaestionesonomaOOneum UINIV|R§ITY OF UReANA<$HAMPAlG.M CCASSICS DISSEETATIO INAVGVRALIS QVAM AVCTORITATE ET CONSENSV AMPLISSIMI PHILOSOPHORVM IN ACADEMIA PHILIPPINA MARPVRGENSI ORDINIS AD SVMMOS IN PHILOSOPHIA HONORES RITE CAPESSENDOS SCRIPSIT RVDOLF NEVMANN COLBERGENsfs (BORVSSVS) MARPURGI CATTORUM TYPIS CAROLI GEORGI TYPOGRAPHI ACADEMICI MCMXV Dissertatio ab aniplissimo pbilosoplionim ordiue referente ERNESTO MAASS probata est a. d. lil. ID. DEC. anni hr/nied in Germany Patri optimo THEODORO NEVMANN Colbergensi has studiorum primitias d. d. d. (lie natali sexagesimo sexto a. d. X. Kal. Quint. anni 1914 gratissimus filius Capitiim elenchiis I Nomina Graecorum propria a flnminibus dcrivata 1 Hominum nomina 2 Gentilicia apud IUyrios in Magna Graecia apud Romanos Gallos Hispanos Graecos Thraces Scythas in Asia Minore apud Orientales II 1 Nomina propria a fluviis ducta in Aeneide a fluviis Ita- liae Mag-nae Graeciae Siciliae Galliae Graeciae Asiae Minoris Thraciae Orientis 2 Nomina propria a fluminibus sumpta in SiH Italici Punicis a) Poenorum eorumque auxiliorum a fluviis Africae Asiae Minoris Hispaniae Italiae et Siciliae Susianae Sarmatiae b) Hispanorum a fluviis Hispaniae Asiae Minoris c) Celtarum ab amnibus Gallieis d) Saguntinorum a fluviis Hispaniae Mag-nae Graeciae Aetoliae .Asiae Minoris e) Romanorum a fluviis Galliae Italiae Asiae Minoris . III 1 Graecorum nomina in Aeneide 2 Lyciorum 3 Phrygum Mysorum Lydorum Bithynorum 4 Troianorum a) Graeca b) -

Naming Effects in Lucretius' De Rerum Natura

Antonomasia, Anonymity, and Atoms: Naming Effects in Lucretius’ DRN Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Antonomasia, Anonymity, and Atoms: Naming Effects in Lucretius’ De rerum natura Version 1.0 September 2009 Wilson H. Shearin Stanford University Abstract: This essay argues that selected proper names within Lucretius’ De rerum natura, rather than pointing deictically or referring with clear historical specificity, instead render Lucretius’ poem vaguer and more anonymous. To make this case, the essay first briefly surveys Roman naming practices, ultimately focusing upon a specific kind of naming, deictic naming. Deictic naming points (or attempts to point) to a given entity and often conjures up a sense of the reality of that entity. The essay then studies the role of deictic naming within Epicureanism and the relationship of such naming to instances of naming within De rerum natura. Through analysis of the nominal disappearance of Memmius, the near nominal absence of Epicurus, and the deployment of Venus (and other names) within the conclusion to Lucretius’ fourth book, the essay demonstrates how selected personal names in De rerum natura, in contrast to the ideal of deictic naming, become more general, more anonymous, whether by the substitution of other terms (Memmius, Epicurus), by referential wandering (Venus), or by still other means. The conclusion briefly studies the political significance of this phenomenon, suggesting that there is a certain popular quality to the tendency towards nominal indefiniteness traced in the essay. © Wilson H. Shearin. [email protected] 1 Antonomasia, Anonymity, and Atoms: Naming Effects in Lucretius’ DRN Antonomasia, Anonymity, and Atoms: Naming Effects in Lucretius’ De rerum natura Poet, patting more nonsense foamed From the sea, conceive for the courts Of these academies, the diviner health Disclosed in common forms. -

Histoire Romaine

HISTOIRE ROMAINE EUGÈNE TALBOT PARIS - 1875 AVANT-PROPOS PREMIÈRE PARTIE. — ROYAUTÉ CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. SECONDE PARTIE. — RÉPUBLIQUE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. - CHAPITRE IV. - CHAPITRE V. - CHAPITRE VI. - CHAPITRE VII. - CHAPITRE VIII. - CHAPITRE IX. - CHAPITRE X. - CHAPITRE XI. - CHAPITRE XII. - CHAPITRE XIII. - CHAPITRE XIV. - CHAPITRE XV. - CHAPITRE XVI. - CHAPITRE XVII. - CHAPITRE XVIII. - CHAPITRE XIX. - CHAPITRE XX. - CHAPITRE XXI. - CHAPITRE XXII. TROISIÈME PARTIE. — EMPIRE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. AVANT-PROPOS. LES découvertes récentes de l’ethnographie, de la philologie et de l’épigraphie, la multiplicité des explorations dans les diverses contrées du monde connu des anciens, la facilité des rapprochements entre les mœurs antiques et les habitudes actuelles des peuples qui ont joué un rôle dans le draine du passé, ont singulièrement modifié la physionomie de l’histoire. Aussi une révolution, analogue à celle que les recherches et les œuvres d’Augustin Thierry ont accomplie pour l’histoire de France, a-t-elle fait considérer sous un jour nouveau l’histoire de Rome et des peuples soumis à son empire. L’officiel et le convenu font place au réel, au vrai. Vico, Beaufort, Niebuhr, Savigny, Mommsen ont inauguré ou pratiqué un système que Michelet, Duruy, Quinet, Daubas, J.-J. Ampère et les historiens actuels de Rome ont rendu classique et populaire. Nous ne voulons pas dire qu’il ne faut pas recourir aux sources. On ne connaît l’histoire romaine que lorsqu’on a lu et étudié Salluste, César, Cicéron, Tite-Live, Florus, Justin, Velleius, Suétone, Tacite, Valère Maxime, Cornelius Nepos, Polybe, Plutarque, Denys d’Halicarnasse, Dion Cassius, Appien, Aurelius Victor, Eutrope, Hérodien, Ammien Marcellin, Julien ; et alors, quand on aborde, parmi les modernes, outre ceux que nous avons nommés, Machiavel, Bossuet, Saint- Évremond, Montesquieu, Herder, on comprend l’idée, que les Romains ont développée dans l’évolution que l’humanité a faite, en subissant leur influence et leur domination. -

Lays of Ancient Rome

Lays of Ancient Rome Thomas Babbington Macaulay The Project Gutenberg Etext of Lays of Ancient Rome, by Macaulay Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babbington Macaulay March, 1997 [Etext #847] The Project Gutenberg Etext of Lays of Ancient Rome, by Macaulay *****This file should be named lrome10.txt or lrome10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, lrome11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, lrome10a.txt. Made by David Reed of [email protected] and [email protected]. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. The official release date of all Project Gutenberg Etexts is at Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. A preliminary version may often be posted for suggestion, comment and editing by those who wish to do so. -

Lays of Ancient Rome by Thomas Babington Macaulay

% nvy tkvr /S^lU, CsUdx *TV IrrTCV* U- tv/ <n\V ftjw ^ Jl— i$fO-$[ . To live ^ Iz^l.cL' dcn^LU *~d |V^ ^ <X ^ ’ tri^ v^X H c /f/- v »»<,<, 4r . N^P’iTH^JJs y*^ ** 'Hvx ^ / v^r COLLECTION OF BRITISH AUTHORS. VOL. CXCVIII. LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME BY THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. IN ONE VOLUME. TATJCHNITZ EDITION". By the same Author, THE HISTORY OF ENGLAND.10 vols. CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL ESSAYS.5 vols. SPEECHES .2 vols. BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS.1 vol. WILLIAM PITT, ATTERBURY.1 VOl. THE LIFE AND LETTERS OF LORD MACAULAY. By his Nephew GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P.4 vols. SELECTIONS FROM THE WRITINGS OF LORD MACAULAY. Edited by GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, M.P. * . 2 vols. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/laysofancientrom00maca_3 LAYS OF ANCIENT ROME: WITH IVEY” AND “THE AEMADA” THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. COPYRIGHT EDITION, LEIPZIG BERNHARD TAUCIINITZ 1851. CONTENTS. Page PREFACE . i HORATIUS.35 THE BATTLE OF THE LAKE REGILLUS.81 VIRGINIA.143 THE PROPHECY OF CAPYS.189 IVRY: A SONG OF THE HUGUENOTS ..... 221 THE ARMADA: A FRAGMENT.231 4 PREFACE. That what is called the history of the Kings and early Consuls of Rome is to a great extent fabulous, few scholars have, since the time of Beaufort, ven¬ tured to deny. It is certain that, more than three hundred and sixty years after the date ordinarily assigned for the foundation of the city, the public records were, with scarcely an exception, destroyed by the Gauls. It is certain that the oldest annals of the commonwealth were compiled more than a cen¬ tury and a half after this destruction of the records. -

The Lacus Curtius in the Forum Romanum and the Dynamics of Memory

THE LACUS CURTIUS IN THE FORUM ROMANUM AND THE DYNAMICS OF MEMORY A contribution to the study of memory in the Roman Republic AUTHOR: PABLO RIERA BEGUÉ SUPERVISOR: NATHALIE DE HAAN MA ETERNAL ROME 15/08/2017 ACKNOLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Nathalie de Haan of the Faculty of arts at Radboud University. She was always willing to help whenever I ran into a trouble spot or had a question about my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Jeremia Pelgrom, director of studies in archaeology at the KNIR, for his invaluable advice on the present research. Without their passionate participation and input, I would not have been able to achieve the present result. I would also like to acknowledge the Koninklijk Nederlands Instituut Rome to permit me to conduct great part of my research in the city of Rome. This thesis would not have been possible without its generous scholarship program for MA students. Finally, I must express my very profound gratitude to my parents and Annelie de Graaf for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my year of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. 1 Content INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 3 1. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................ 6 1.1 The evolution of ‘memory studies’ -

A Római Nép Története a Város Alapításától 2

TITUS LIVIUS A RÓMAI NÉP TÖRTÉNETE A VÁROS ALAPÍTÁSÁTÓL FORDÍTOTTA ÉS A JEGYZETANYAGOT ÖSSZEÁLLÍTOTTA MURAKÖZY GYULA ÖTÖDIK KÖNYV HATODIK KÖNYV HETEDIK KÖNYV NYOLCADIK KÖNYV KILENCEDIK KÖNYV TIZEDIK KÖNYV NÉVMUTATÓ MÁSODIK KÖTET 2 ÖTÖDIK KÖNYV 1. Mindenütt béke volt már megint, csak a rómaiak és a veiibeliek álltak harcra készen, olyan indulattal és gyűlölettel eltelve, hogy a legyőzöttre nyilvánvaló pusztulás várt. A két nép választási gyűlései nagyon eltérő módon zajlottak le. A rómaiak a consuli jogkörrel felruházott katonai tribunusok számát - most először - nyolcra emelték, és a következőket választották meg: M. Aemilius Mamercust (másodszor), L. Valerius Potitust (harmadszor), Ap. Claudius Crassust, M. Quinctilius Varust, L. Iulius Iulust, M. Postumiust, M. Furius Camillust és M. Postumius Albinust. A veiibeliek viszont, megelégelve az évenként megújuló s nemegyszer viszálykodást okozó választási küzdelmet, királyt választottak. Ez sértette Etruria népeit, amelyek egyaránt gyűlölték a királyságot és személy szerint a királyt is, aki hatalmaskodásával és gőgjével már korábban is terhére volt a lakosságnak. Az ünnepi játé- kokat ugyanis, amelyeknek megzavarása szentségtörésszámba ment, durván félbeszakította, mert a tizenkét nép mást választott meg helyette főpapnak. S feldühödve a mellőzésen, mikor már javában folytak a játékok, váratlanul visszarendelte a szereplőket, akik nagyrészt az ő rabszolgái voltak. Ezért a népek, amelyek mindennél jobban tisztelték a vallási szertartásokat, minthogy ezek ápolásában tűntek ki leginkább, elhatározták,