Towards Strengths-Based Planning Strategies for Rural Localities in Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kauppa-Alue 1 Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Länsi- Turunmaa Pirkkala

Kauppa-alue 1 Länsi- Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Turunmaa Pirkkala Siuntio Asikkala Hämeenkyrö Kiikoinen Marttila Pomarkku Somero Askola Hämeenlinna Kirkkonummi Masku Pori Sysmä Aura Iitti Kokemäki Miehikkälä Pornainen Säkylä Espoo Ikaalinen Koski Mynämäki Porvoo Taivassalo Eura Imatra Kotka Myrskylä Pukkila Tammela Eurajoki Inkoo Kouvola Mäntsälä Punkalaidun Tampere Forssa Janakkala Kuhmoinen Mäntyharju Pyhtää Tarvasjoki Hamina Jokioinen Kustavi Naantali Pyhäranta Turku Hanko Juupajoki Kärkölä Nakkila Pälkäne Tuusula Harjavalta Jämijärvi Köyliö Nastola Pöytyä Ulvila Hartola Jämsä 1) Lahti Nokia Raasepori Urjala Hattula Järvenpää Laitila Nousiainen Raisio Uusikaupunki Hausjärvi Kaarina Lapinjärvi Nummi-Pusula Rauma Valkeakoski Heinola Kangasala Lieto Nurmijärvi Riihimäki Vantaa Helsinki Kankaanpää Lohja Orimattila Rusko Vehmaa Hollola Karjalohja Loimaa Oripää Salo Vesilahti Huittinen Karkkila Loviisa Orivesi Sastamala Vihti Humppila Kauniainen Luumäki Padasjoki Sauvo Virolahti Hyvinkää Kemiönsaari Luvia Paimio Sipoo Ylöjärvi 2) 1) Lukuun ottamatta entisten Jämsänkosken ja Kuoreveden kuntien alueita, jotka kuuluvat kauppa-alueeseen 2 2) Lukuun ottamatta entisen Kurun kunnan aluetta, joka kuuluu kauppa-alueeseen 2 Kauppa-alue 2 Alajärvi Joutsa 7) Kesälahti 7) Lappajärvi Nilsiä 7) Pyhäjärvi Soini Vieremä 7) Alavieska Juankoski 7) Keuruu 7) Lapua Nivala Pyhäntä Sonkajärvi Vihanti Alavus Juva Kihniö Laukaa Närpiö Raahe Sulkava 7) Viitasaari Enonkoski 7) Jyväskylä 7) Kinnula Leppävirta 7) Oulainen Rantasalmi 7) Suomenniemi 7) Vimpeli Evijärvi Jämsä -

Kirje 09 Liite SRP

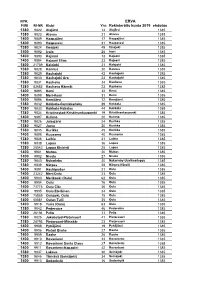

NYK. ERVA PIIRI RI-NR Klubi Yht: Rekisteröity kunta 2019 ehdotus 1380 9822 Alajärvi 14 Alajärvi 1385 1380 9823 Alavus 21 Alavus 1385 1400 9889 Haapajärvi 17 Haapajärvi 1385 1400 9890 Haapavesi 31 Haapavesi 1385 1380 9824 Ilmajoki 49 Ilmajoki 1385 1400 9892 Ivalo 28 Inari 1385 1400 9893 Kajaani 13 Kajaani 1385 1400 9894 Kajaani Elias 33 Kajaani 1385 1400 21739 Kalajoki 21 Kalajoki 1385 1380 9828 Kannus 30 Kannus 1385 1380 9829 Kauhajoki 42 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9830 Kauhajoki Aro 24 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9831 Kauhava 34 Kauhava 1385 1380 83683 Kauhava Härmät 23 Kauhava 1385 1400 9895 Kemi 32 Kemi 1385 1400 9899 Meri-Kemi 31 Kemi 1385 1400 9896 Kemijärvi 12 Kemijärvi 1385 1380 9832 Kokkola-Gamlakarleby 29 Kokkola 1385 1380 9833 Kokkola-Hakalax 44 Kokkola 1385 1380 9834 Kristinestad-Kristiinankaupunki 19 Kristiinankaupunki 1385 1400 9897 Kuhmo 20 Kuhmo 1385 1380 9826 Jalasjärvi 24 Kurikka 1385 1380 9827 Jurva 20 Kurikka 1385 1380 9835 Kurikka 45 Kurikka 1385 1400 9898 Kuusamo 40 Kuusamo 1385 1380 9836 Laihia 31 Laihia 1385 1380 9838 Lapua 36 Lapua 1385 1380 25542 Lapua Kiviristi 25 Lapua 1385 1400 9901 Muhos 20 Muhos 1385 1400 9902 Nivala 27 Nivala 1385 1380 9840 Nykarleby 40 Nykarleby-Uusikaarlepyy 1385 1380 9839 Närpes 28 Närpes-Närpiö 1385 1400 9891 Haukipudas 21 Oulu 1385 1400 23242 Meri-Oulu 23 Oulu 1385 1400 9900 Merikoski (Oulu) 62 Oulu 1385 1400 9904 Oulu 76 Oulu 1385 1400 73778 Oulu City 36 Oulu 1385 1400 9905 Oulu Eteläinen 34 Oulu 1385 1400 75859 Oulujoki, Oulu 15 Oulu 1385 1400 50881 Oulun Tulli 35 Oulu 1385 1400 9918 Tuira (Oulu) -

39 DOUZELAGE CONFERENCE SIGULDA 24 April – 27 April 2014

AGROS (CY) ALTEA (E) ASIKKALA (FIN) th BAD KÖTZTING (D) 39 DOUZELAGE CONFERENCE BELLAGIO (I) BUNDORAN (IRL) CHOJNA (PL) GRANVILLE (F) HOLSTEBRO (DK) HOUFFALIZE (B) JUDENBURG (A) SIGULDA KÖSZEG (H) MARSASKALA (MT) MEERSSEN (NL) NIEDERANVEN (L) OXELÖSUND (S) th th PREVEZA (GR) 24 April – 27 April 2014 PRIENAI (LT) SESIMBRA (P) SHERBORNE (GB) SIGULDA (LV) SIRET (RO) SKOFIA LOKA (SI) MINUTES SUŠICE (CZ) TRYAVNA (BG) TÜRI (EST) ZVOLEN (SK) DOUZELAGE – EUROPEAN TOWN TWINNING ASSOCIATION PARTICIPANTS AGROS Andreas Latzias Metaxoula Kamana Alexis Koutsoventis Nicolas Christofi ASIKKALA Merja Palokangos-Viitanen Pirjo Ala-Hemmila Salomaa Miika BAD KOTZTING Wolfgang Kershcer Agathe Kerscher Isolde Emberger Elisabeth Anthofer Saskia Muller-Wessling Simona Gogeissl BELLAGIO Donatella Gandola Arianna Sancassani CHOJNA Janusz Cezary Salamończyk Norbert Oleskow Rafał Czubik Andrzej Będzak Anna Rydzewska Paweł Woźnicki BUNDORAN Denise Connolly Shane Smyth John Campbell GRANVILLE Fay Guerry Jean-Claude Guerry HOLSTEBRO Jette Hingebjerg Mette Grith Sorensen Lene Bisgaard Larsen Victoria Louise Tilsted Joachim Peter Tilsted 2 DOUZELAGE – EUROPEAN TOWN TWINNING ASSOCIATION HOUFFALIZE Alphonse Henrard Luc Nollomont Mathilde Close JUDENBURG Christian Fuller Franz Bachmann Andrea Kober Theresa Hofer Corinna Haasmann Marios Agathocleous KOSZEG Peter Rege Kitti Mercz Luca Nagy Aliz Pongracz MARSASKALA Mario Calleja Sandro Gatt Charlot Mifsud MEERSSEN Karel Majoor Annigje Luns-Kruytbosch Ellen Schiffeleers Simone Borm Bert Van Doorn Irene Raedts NIEDERANVEN Jos -

Carbon Neutral Päijät-Häme 2030: Climate Action Roadmap

Carbon Neutral Päijät-Häme 2030: Climate Action Roadmap ENTER The Regional Council of Päijät-Häme Carbon Neutral Päijät-Häme 2030: Climate Action Roadmap Päijät-Häme region is committed to mitigating 2030. The network is coordinated by the Finnish climate change with an aim of reaching carbon Environment Institute. neutrality by the year 2030. This requires significant reductions of greenhouse gas The Climate Action Roadmap presents actions emissions at all sectors as well as increasing towards carbon neutrality. The Roadmap is carbon sinks. updated annually, and future development targets include climate change adaptation, actions on Päijät-Häme region achieved a Hinku (Towards increasing carbon sinks and indicators to follow Carbon Neutral Municipalities) region status the progress. The Roadmap is a part of national in 2019. The national Hinku network brings Canemure project supported by EU Life program. together forerunner municipalities and regions, which are committed to an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 2007 levels by ROADMAP Read more: STAKEHOLDERS CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS Stakeholders Climate action requires broad cooperation with different stakeholders including municipalities, companies, higher education institutions and regional actors. Päijät-Häme climate coordination group steers regional activities, and the Regional Council of Päijät-Häme facilitates the work of coordination group. Kymenlaakson Sähkö: Lahti Energy ltd: Heikki Rantula heikki.rantula@ksoy.fi Eeva Lillman eeva.lillman@lahtienergia.fi -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Linna, Paula; Pekkarinen, Satu; Tura, Tomi Conference Paper Developing a Regional Service Cluster. Case: Setting Up a Social Affairs and Health District in Päijät- Häme, Finland 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Linna, Paula; Pekkarinen, Satu; Tura, Tomi (2006) : Developing a Regional Service Cluster. Case: Setting Up a Social Affairs and Health District in Päijät-Häme, Finland, 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118322 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Entangled Beliefs and Rituals Religion in Finland and Sάpmi from Stone Age to Contemporary Times

- 1 - ÄIKÄS, LIPKIN & AHOLA Entangled beliefs and rituals Religion in Finland and Sάpmi from Stone Age to contemporary times Tiina Äikäs & Sanna Lipkin (editors) MONOGRAPHS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF FINLAND 8 Published by the Archaeological Society of Finland www.sarks.fi Layout: Elise Liikala Cover image: Tiina Äikäs Copyright © 2020 The contributors ISBN 978-952-68453-8-8 (online - PDF) Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland ISSN-L 1799-8611 Entangled beliefs and rituals Religion in Finland and Sάpmi from Stone Age to contemporary times MONOGRAPHS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF FINLAND 8 Editor-in-Chief Associate Professor Anna-Kaisa Salmi, University of Oulu Editorial board Professor Joakim Goldhahn, University of Western Australia Professor Alessandro Guidi, Roma Tre University Professor Volker Heyd, University of Helsinki Professor Aivar Kriiska, University of Tartu Associate Professor Helen Lewis, University College Dublin Professor (emeritus) Milton Nunez, University of Oulu Researcher Carl-Gösta Ojala, Uppsala University Researcher Eve Rannamäe, Natural Resources Institute of Finland and University of Tartu Adjunct Professor Liisa Seppänen, University of Turku and University of Helsinki Associate Professor Marte Spangen, University of Tromsø - 1 - Entangled beliefs and rituals Religion in Finland and Sápmi from Stone Age to contemporary times Tiina Äikäs & Sanna Lipkin (editors) Table of content Tiina Äikäs, Sanna Lipkin & Marja Ahola: Introduction: Entangled rituals and beliefs from contemporary times to -

Geologisia Havaintoja Päijänne-Tunnelista 1

GEOLOGINEN TUTKIMUSLAITOS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF FINLAND TUTKIMUSRAPORTTI N:o 37 REPORT OF INVESTIGA TION No. 37 Ilkka Laitakari ja Eero Pokki Geologisia havaintoja Päijänne-tunnelista 1. Rakennusjakso, HI. Koski - Asikkala Summary: Geological observations from the Päijänne Tunnel, construction phase 1, HI. Koski - Asikkala Espoo 1979 GEOLOGINEN TUTKIMUSLAITOS GEOLOGICAL SUR VEY OF FINLAND Tutkimusraportti n:o 37 Report of Investigation no . 37 • llkka Laitakari ja Eero Pokki GEOLOGISIA HAVAINTOJA PÄljÄNNE-TUNNELISTA 1. RAKENNUSJAKSO, HL. KOSKI - ASIKKALA Summary: Geological observations from the Päijänne tunnel, construction phase 1, HI. Koski-Asikkala Espoo 1979 2 Laitakari, I. & Pokki E., 1979. Geologisia havaintoja Päijänne-tunnelista, I . rakennusjakso, HI. Koski - Asikkala. Summary: Geological observations from the Päijänne tunnel, construc tion phase I, HI. Koski - Asikkala. Geo~ogical Survey of Finland, Report of Investigation 00. ·37.23 pages, 2 figures, 3 plates and I appendix . The Päijänne tunnel will be, when ready (in 1982), 120 km long, with a cross section of 15 .5 m2 • It is being built through bedrock to conduct fresh water from Lake Päijänne to the Helsinki metropolitan area. This paper deals with geological observations made in the tunnel along the northemmost 35 km , built in 1973 - 1976. The bedrock belongs to the Svecokareli dic migmatite zone 01" southern Finland, migmatitic granite and mica gneiss being the most ab undant rocks in the research area. A lithological map on the scale of 1:20 000 is appended. Shearing, fracture and fault zones have been investigated from the point of view of engineer ing geology. The effect of the tunnel on the ground-water conditions is discussed. -

Ohjeet Vammaispalvelulain Mukaisten Kuljetuspalvelujen Käyttäjille

OHJEET VAMMAISPALVELULAIN MUKAISTEN KULJETUSPALVELUJEN KÄYTTÄJILLE 5.2.2020 / kuljetuspalveluohje 1 Kuljetuspalvelun käyttö 30.3.2020 alkaen matkat tilataan uuden välityskeskuksen kautta, jonka palveluntuottajana toimii FCG Smart Transportation Oy. Palvelu kattaa vammaispalvelulain mukaisten kuljetusten lisäksi myös sosiaalihuoltolain- ja erityishuoltolain matkojen välitys- ja kuljetuspalvelut PHHYKY:n toiminta-alueella. Kuljetuspalvelukokonaisuuden nimi on nyt ”Hyky- kyyti”. Kuljetuspalveluna korvataan asuinkunnassa, lähikunnassa tai toiminnallisessa lähikunnassa tapahtuvat kohtuulliset matkat. Kuljetuspalvelu perustuu asiakkaalle myönnettyyn matkaoikeuteen, josta asiakkaalla on erillinen, viranhaltijan myöntämä kirjallinen päätös. Kuljetukset tilataan välityspalvelukeskuksen kautta puhelimitse, sähköpostilla, tekstiviestillä tai tilaussovelluksen kautta. Tilaaminen on maksutonta. Välityskeskus lähettää asiakkaalle tilausvahvistuksen matkasta asiakkaan haluamalla tavalla (puhelu, tekstiviesti, sähköposti, tilaussovellus, jossa saatavilla myös puheohjaus). Kuljettaja avustaa asiakasta kuljetukseen välittömästi liittyvissä asioissa sekä on vastuussa asiakkaan turvallisesta pääsystä ajoneuvoon sekä ajoneuvosta määränpäähän. Asiakas ei tarvitse erillistä matkakorttia. Välityskeskus ylläpitää asiakkaasta kuljetuksen kannalta välttämättömiä asiakastietoja (myönnetty matkaoikeus, matkojen määrä, apuvälineet yms.) Kuljetuspalveluoikeus on henkilökohtainen. Asiakkaalla tulee olla matkalla mukana henkilöllisyystodistus, joka esitetään kuljettajalle -

A Finnic Holy Word and Its Subsequent History

A Finnic Holy Word and its Subsequent History BY MAUNO KOSKI This article concentrates on a specific ancient holy word in Finnic and its subsequent development.' The word in question is hiisi. In- flection contains a strong vowel stem (basic phonological form) in hide+ , a weak vowel stem in hiibe+, a consonant stem in hiit+, e.g, Finnish hiisi, illative sing. hiiteen, genitive sing. hiiden, partitive sing. hiittä; Estonian (h)iis, genitive sing. (h)iie. Estonian and Finnish, particularly western Finnish dialects, allow us to conclude that the primary sense of the word, at least comparatively speaking, is 'cult place', or possibly — at an earlier stage — even 'burial place'. The sporadic appearance of hii(t)ta in Finnish and Estonian place names and folklore is clearly a secondary phenomenon (see Koski 1967-70, 2, 234 ff.). Labial vowel derivatives are Estonian hiid (genitive sing. hiiu), and Finnish, Karelian and Ingrian hiito hiitto) and hitto, all of which suggest their origin in Finnic *hiito(i). These were originally possessive derivatives signifying a relationship to the concept of 'Hsi' in its broadest sense. The derivative hittunen, 'ghost, spirit of the dead', appears in central Óstrobothnian dialects. Ä number of place names indicate that, alongside the inflection model hiisi: hiite+ , there existed a non-assibilated type hiiti: hiite+ hiiti,2 This article is largely based on my earlier research work (Koski 1967-70; see also Koski 1977), but I have also included certain other data published subse- quently. I have decided to take the subject up here because my previous study has only appeared in Finnish, apart from a short paper in English on the theoretical methodology of my work, semantic component analysis. -

Kuntakohtaiset Rajat 2018 Vuokramenon Lisäksi Hyväksytään Vesimaksuna 21,60 E / Henkilö

Perustoimeentulotuessa hyväksyttävien vuokramenojen kuntakohtaiset rajat 2018 Vuokramenon lisäksi hyväksytään vesimaksuna 21,60 e / henkilö. 2 hengen perhe, 3 hengen perhe, 4 hengen perhe, + lisähenkilöä Kunta Yksin asuva, e/kk e/kk e/kk e/kk kohden e/kk Akaa 522 600 686 785 96 Alajärvi 465 560 657 710 96 Alavieska 444 485 621 631 96 Alavus 420 500 594 725 96 Asikkala 479 601 710 801 96 Askola 464 604 737 805 96 Aura 457 508 623 691 96 Enonkoski 432 562 650 715 96 Enontekiö 456 560 627 680 96 Espoo 673 828 914 1027 111 Eura 428 548 600 650 96 Eurajoki 458 583 607 638 96 Evijärvi 445 545 630 685 96 Forssa 429 571 689 786 96 Haapajärvi 435 564 658 700 96 Haapavesi 410 546 667 752 96 Hailuoto 505 582 669 725 96 Halsua 478 552 639 716 96 Hamina 478 542 644 769 96 Hankasalmi 445 525 615 676 96 Hanko 530 600 717 752 96 Harjavalta 435 488 550 650 96 Hartola 445 560 660 755 96 Hattula 521 634 679 715 96 Hausjärvi 478 575 680 712 96 Heinola 398 557 675 746 96 Heinävesi 372 506 575 658 96 Helsinki 675 824 947 1038 118 Hirvensalmi 445 536 632 684 96 Hollola 495 612 740 860 96 Honkajoki 404 502 567 628 96 Huittinen 390 480 570 632 96 Humppila 440 588 708 786 96 Hyrynsalmi 467 568 640 693 96 Hyvinkää 558 650 769 861 104 Hämeenkyrö 442 558 692 796 96 Hämeenlinna 592 676 795 836 104 Ii 478 588 658 700 96 Iisalmi 440 570 663 749 96 Iitti 437 566 669 769 96 Ikaalinen 408 597 738 814 96 Ilmajoki 432 534 607 645 96 Ilomantsi 388 528 607 654 96 Imatra 474 571 688 725 96 Inari 470 599 627 680 96 Perustoimeentulotuessa hyväksyttävien vuokramenojen kuntakohtaiset rajat 2018 Vuokramenon lisäksi hyväksytään vesimaksuna 21,60 e / henkilö. -

Handboek Herkomstregio Vleeskalveren

Handboek Herkomstregio Vleeskalveren Stichting Kwaliteitsgarantie Vleeskalversector Stichting Kwaliteitsgarantie Vleeskalversector Handboek Herkomstregio Vleeskalveren S.W. van Beers Versie 2: juli 2014 50Handboek Handboek Herkomstregi Herkomstregio Pagina 2 van 50 Vleeskalveren Voorwoord Voor u ligt het Handboek Herkomstregio Vleeskalveren. Acht weken heb ik mij hier met veel plezier voor ingezet. Achteraf heeft het onderzoek wat langer geduurd dan ik had verwacht, het ontvangen van antwoorden uit het buitenland liet op zich wachten. Soms zelfs zo lang dat ik na vier weken en verschillende herinneringen later helaas nog geen antwoord heb mogen ontvangen. Al met al ben ik erg tevreden met het eindresultaat. Als derdejaars Dier- en Veehouderij studente heb ik dit onderzoek in opdracht van SKV mogen uitvoeren, hierin wil ik graag mijn collega’s bedanken voor hun medewerking en gezelligheid op kantoor. Daarnaast wil ik graag mijn stagebegeleider Michel Wesselink bedanken voor zijn ondersteuning bij de vragen die ik had omtrent het schrijven van dit handboek en het geven van kansen om meerdere aspecten van de Vleeskalversector van dichtbij mee te mogen maken. Ik kijk terug op acht hele leuke weken stage, ik hoop dat jullie met net zo veel plezier dit handboek lezen. Sanne van Beers Zeist, 8 oktober 2013 50Handboek Handboek Herkomstregi Herkomstregio Pagina 3 van 50 Vleeskalveren Inleiding Begin 2013 brak BVD-type 2 in Duitsland uit. Deze besmettelijke ziekte werd alleen geconstateerd in bepaalde regio’s van Duitsland. Het bestuur van de SKV besloot daarop de import vanuit deze regio’s te kanaliseren en daarmee niet heel Duitsland een importverbod op te leggen, immers worden alle kalveren uit Oost-Europa door Duitsland getransporteerd. -

Finland Land of Islands and Waters the Sulkava Rowing Race Is the Larg- Est Rowing Event in the World

The Island Committee Finland Land of Islands and Waters doubles racestoo. ways plentyofentriesforthesinglesand al are butthere is particularlypopular, boatraceforteams 60 km.Thechurch PartalansaariIslandextendsover around eventintheworld.Theroute est rowing The SulkavaRowingRace isthelarg - - Antero AAltonen • Front cover photo: Anne SAArinen / VastAvAlo Finland – land oF islands and wATERS 3 Dear Reader This brochure describes life, sources of livelihood and nature on islands with no permanent road connections, on islands with permanent road connections and in island-like areas in Finland. Finland is the country richest in waters and more of the richest in islands in Europe. We boast 76,000 islands with an area of 0.5 hectares or more, 56,000 lakes with an area of one hectare or more, 36,800 kilome- tres of river bed wider than fi ve metres and 336,000 kilometres of shore- eemeli / peltonen vAStAvAlo line. Every Finnish municipality has waters, and most contain islands. The number of islands with either permanent or part-time inhabitants amounts to around 20,000. Every island, lake and river has its place in the hearts of Finns. This brochure describes these unique riches. Its multitude of islands and waters makes the Finnish landscape frag- mented, creating extra costs for the economy, the State and local author- ities, but it is also an incomparable resource. Our islands, seas, lakes, riv- ers and shores are excellent regional assets in a world that thrives increas- ingly on producing unique experiences. Island municipalities and part- island municipalities boast a large range of sources of livelihood, although structural changes have decreased the number of jobs over the years.