Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kauppa-Alue 1 Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Länsi- Turunmaa Pirkkala

Kauppa-alue 1 Länsi- Akaa Hämeenkoski Kerava Turunmaa Pirkkala Siuntio Asikkala Hämeenkyrö Kiikoinen Marttila Pomarkku Somero Askola Hämeenlinna Kirkkonummi Masku Pori Sysmä Aura Iitti Kokemäki Miehikkälä Pornainen Säkylä Espoo Ikaalinen Koski Mynämäki Porvoo Taivassalo Eura Imatra Kotka Myrskylä Pukkila Tammela Eurajoki Inkoo Kouvola Mäntsälä Punkalaidun Tampere Forssa Janakkala Kuhmoinen Mäntyharju Pyhtää Tarvasjoki Hamina Jokioinen Kustavi Naantali Pyhäranta Turku Hanko Juupajoki Kärkölä Nakkila Pälkäne Tuusula Harjavalta Jämijärvi Köyliö Nastola Pöytyä Ulvila Hartola Jämsä 1) Lahti Nokia Raasepori Urjala Hattula Järvenpää Laitila Nousiainen Raisio Uusikaupunki Hausjärvi Kaarina Lapinjärvi Nummi-Pusula Rauma Valkeakoski Heinola Kangasala Lieto Nurmijärvi Riihimäki Vantaa Helsinki Kankaanpää Lohja Orimattila Rusko Vehmaa Hollola Karjalohja Loimaa Oripää Salo Vesilahti Huittinen Karkkila Loviisa Orivesi Sastamala Vihti Humppila Kauniainen Luumäki Padasjoki Sauvo Virolahti Hyvinkää Kemiönsaari Luvia Paimio Sipoo Ylöjärvi 2) 1) Lukuun ottamatta entisten Jämsänkosken ja Kuoreveden kuntien alueita, jotka kuuluvat kauppa-alueeseen 2 2) Lukuun ottamatta entisen Kurun kunnan aluetta, joka kuuluu kauppa-alueeseen 2 Kauppa-alue 2 Alajärvi Joutsa 7) Kesälahti 7) Lappajärvi Nilsiä 7) Pyhäjärvi Soini Vieremä 7) Alavieska Juankoski 7) Keuruu 7) Lapua Nivala Pyhäntä Sonkajärvi Vihanti Alavus Juva Kihniö Laukaa Närpiö Raahe Sulkava 7) Viitasaari Enonkoski 7) Jyväskylä 7) Kinnula Leppävirta 7) Oulainen Rantasalmi 7) Suomenniemi 7) Vimpeli Evijärvi Jämsä -

Koulu- Ja Linja-Autokuljetusten Tasoristeysturvallisuus Rataosat LAHTI–HEINOLA JA LAHTI–LOVIISAN SATAMA

48 • 2014 LIIKENNEVIRASTON TUtkIMUKSIA JA SELVITYKSIÄ MARKUS LAINE MIKKO POUTANEN Koulu- ja linja-autokuljetusten tasoristeysturvallisuus RATAOSAT LAHTI–HEINOLA JA LAHTI–LOVIISAN SATAMA Markus Laine, Mikko Poutanen Koulu- ja linja-autokuljetusten tasoristeysturvallisuus Rataosat Lahti–Heinola ja Lahti–Loviisan satama Liikenneviraston tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä 48/2014 Liikennevirasto Helsinki 2014 Kannen kuva: Markus Laine Verkkojulkaisu pdf (www.liikennevirasto.fi) ISSN-L 1798-6656 ISSN 1798-6664 ISBN 978-952-317-024-7 Liikennevirasto PL 33 00521 HELSINKI Puhelin 029 534 3000 3 Markus Laine, Mikko Poutanen: Koulu- ja linja-autokuljetusten tasoristeysturvallisuus, ra- taosat Lahti – Heinola ja Lahti – Loviisan satama. Liikennevirasto, infra ja ympäristö -osasto. Helsinki 2014. Liikenneviraston tutkimuksia ja selvityksiä 48/2014. 50 sivua ja 8 liitettä. ISSN-L 1798-6656, ISSN 1798-6664, ISBN 978-952-317-024-7. Avainsanat: tasoristeykset, liikenneturvallisuus, liikenneonnettomuudet, koululaiskuljetus, linja- autoliikenne Tiivistelmä Työn tarkoituksena oli kartoittaa rataosien Lahti – Heinola ja Lahti – Loviisan satama ta- soristeykset, joista kulkee koulukuljetuksia tai linja-autoliikennettä. Lisäksi tarkoituk- sena oli esittää tasoristeysturvallisuutta parantavia toimenpidesuosituksia kuljetusten reiteille ja tasoristeyksille sekä ehdottaa muita parannuksia, mikäli tutkimuksen aika- na koulukuljetuksissa ilmenisi puutteita. Rataosat Lahti – Heinola ja Lahti – Loviisan sa- tama valittiin tutkimusalueeksi, koska rataosilla on tapahtunut -

KIERTO KIRJEKÖ KO ELMA 1976 No 51

POSTI- JA LENNATINHALLITUKSEN KIERTO KIRJEKÖ KO ELMA 1976 No 51 No 51 Kiertokirje posti- ja lennätinlaitoksen linjahallinnon jakamisesta postipiireihin sekä postisäännön soveltamismääräysten muuttamisesta Posti- ja lennätinhallitus on tänään istun hola, Tuulos, Tuusula, Vantaa ja Vihti, pii nossa tapahtuneessa esittelyssä, nojautuen rikonttorin asemapaikkana Helsinki. posti-ja lennätinlaitoksesta 12. 2. 1971 an Lounais-Suomen postipiiri, johon kuulu netun asetuksen 26 §:n 2 momenttiin, vah vat seuraavat kunnat: Alastaro, Askainen, vistanut posti- ja lennätinlaitoksen linja- Aura, Dragsfjärd, Eura, Eurajoki, Forssa, hallinnon jaon postipiireihin sekä samalla Halikko, Harjavalta, Honkajoki, Houtskari, muuttanut postisäännön soveltamismää Huittinen, Humppila, Iniö, Jokioinen, Jämi räysten 2 §:n, sellaisena kuin se on kierto järvi, Kaarina, Kalanti, Kankaanpää, Kari- kirjeissä no 127/61 ja 77/71, näin kuulu nainen, Karjala, Karvia, Keikyä, Kemiö, vaksi: Kiikala, Kiikka, Kiikoinen, Kisko, Kiukai nen, Kodisjoki, Kokemäki, Korppoo, Koski 2 S T.I., Kuhaa, Kustavi, Kuusjoki, Köyliö, Lai Postipiirit tila, Lappi, Lavia, Lemu, Lieto, Loimaa, Loimaan mlk, Lokalahti, Luvia, Marttila, 1. Posti- ja lennätinlaitoksen linjahallinto Masku, Mellilä, Merikarvia, Merimasku, Mie on jaettu seuraaviin postipiireihin: toinen, Muurla, Mynämäki, Naantali, Nak Helsingin postipiiri, johon kuuluvat seu- kila, Nauvo, Noormarkku, Nousiainen, Ori- raavat kunnat: Artjärvi, Asikkala, Askola, pää, Paimio, Parainen, Perniö, Pertteli, Piik Bromarv, Espoo, Hanko, -

Labour Market Areas Final Technical Report of the Finnish Project September 2017

Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 1(37) Labour Market Areas Final Technical report of the Finnish project September 2017 Data collection for sub-national statistics (Labour Market Areas) Grant Agreement No. 08141.2015.001-2015.499 Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Postal address: 3rd floor, FI-00022 Statistics Finland E-mail: [email protected] Yrjö Palttila, Statistics Finland, 22 September 2017 Eurostat – Labour Market Areas – Final Technical report – Finland 2(37) Contents: 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work 1.2 Finland’s national travel-to-work areas 1.3 Tasks of the project 2. Results of the Finnish project 2.1 Improving IT tools to facilitate the implementation of the method (Task 2) 2.2 The finished SAS IML module (Task 2) 2.3 Define Finland’s LMAs based on the EU method (Task 4) 3. Assessing the feasibility of implementation of the EU method 3.1 Feasibility of implementation of the EU method (Task 3) 3.2 Assessing the feasibility of the adaptation of the current method of Finland’s national travel-to-work areas to the proposed method (Task 3) 4. The use and the future of the LMAs Appendix 1. Visualization of the test results (November 2016) Appendix 2. The lists of the LAU2s (test 12) (November 2016) Appendix 3. The finished SAS IML module LMAwSAS.1409 (September 2017) 1. Overview 1.1 Objective of the work In the background of the action was the need for comparable functional areas in EU-wide territorial policy analyses. The NUTS cross-national regions cover the whole EU territory, but they are usually regional administrative areas, which are the re- sult of historical circumstances. -

The Dispersal and Acclimatization of the Muskrat, Ondatra Zibethicus (L.), in Finland

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Other Publications in Wildlife Management for 1960 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland Atso Artimo Suomen Riistanhoito-Saatio (Finnish Game Foundation) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Artimo, Atso, "The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland" (1960). Other Publications in Wildlife Management. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmother/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications in Wildlife Management by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. R I 1ST A TIE T L .~1 U ( K A I S U J A ,>""'liSt I " e'e 'I >~ ~··21' \. • ; I .. '. .' . .,~., . <)/ ." , ., Thedi$perscdQnd.a~C:li"'dti~otlin. of ,the , , :n~skret, Ond~trq ~ib.t~i~',{(.h in. Firtland , 8y: ATSO ARTIMO . RllSTATIETEELLISljX JULKAISUJA PAPERS ON GAME RESEARCH 21 The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (l.), in Finland By ATSO ARTIMO Helsinki 1960 SUOMEN FIN LANDS R I 1ST A N HOI T O-S A A T I b ] AK TV ARDSSTI FTELSE Riistantutkimuslaitos Viltforskningsinstitutet Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsingfors, Unionsg. 45 B FINNISH GAME FOUNDATION Game Research Institute Helsinki, Unionink. 45 B Helsinki 1960 . K. F. Puromichen Kirjapaino O.-Y. The dispersal and acclimatization of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus (L.), in Finland By Atso Artimo CONTENTS I. -

PÄIJÄT-HÄMEEN MAAHANMUUTTO-OHJELMA 2021-2025 Sisältö

PÄIJÄT-HÄMEEN MAAHANMUUTTO-OHJELMA 2021-2025 Sisältö 1. Maahanmuutto-ohjelman tarkoitus 4 2. Kotouttaminen ohjelma-alueella 8 3. Maahanmuutto Päijät-Hämeen maahanmuutto-ohjelman alueella 9 4. Tavoite 1: Edistämme työ- ja opiskeluperusteista maahanmuuttoa 11 5. Tavoite 2: Lisäämme maahan muuttaneiden työllisyyttä 13 6. Tavoite 3: Parannamme yhteistyötä ja monipuolisia palveluja maahan muuttaneiden kotoutumisen tukemisessa 15 7. Tavoite 4: Edistämme maahanmuuttoa koskevan keskustelukulttuurin muutosta 18 8. Tavoite 5: Kannamme vastuumme humanitaarisesta maahanmuutosta 19 9. Toimenpiteet ja seuranta 22 10. Lisää tietoa ja apua kotouttamiseen 24 Päijät-Hämeen maahanmuutto-ohjelma 2021-2025 Hyväksytty: Maakuntahallitus 8.2.2021 A251 * 2021 ISBN 978-951-637-264-1 ISSN 1237-6507 Taitto ja kuvitus: Annika Moisio 1. Maahanmuutto-ohjelman tarkoitus Päijät-Hämeen maahanmuutto-ohjelma on eri toimijoiden näkemys, millä keinoin maahanmuut- totyö tukee alueen kasvua ja kehittämistä, sekä miten kotoutumista alueelle vahvistetaan. Päijät-Hämeen maahanmuutto-ohjelman tavoitteena on lisätä työperusteista maahanmuuttoa, maahan muuttaneiden työllisyyttä ja kotoutumista kaikissa kunnissa. Maahanmuutto-ohjelman tärkeänä tavoitteena on myös maahanmuuttajien osallisuuden ja yhteiskunnallisen yhdenvertaisuuden lisääminen. “Päijät-Häme on kansain- Päijät-Hämeen maakuntahallituksen hyväksymä maahanmuutto-ohjelma toimii lain Kotoutumisen edistä- misestä (1386/2010) mukaisena kotouttamisohjelmana kunnissa, jotka ovat hyväksyneet ohjelman kun- nanvaltuustoissaan. Voimassa -

Feasibility of the Jyväskylä - Lahti Railway Connection

Feasibility of the Jyväskylä - Lahti Railway connection Industrial sector Jesse Keränen Bachelor’s thesis May 2020 Technology, communication and transport Degree programme in Logistics engineering Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Keränen Jesse Bachelor’s thesis May 2020 Language of publication: English Number of pages Permission for web publi- 53 cation: x Title of publication Feasibility of Jyväskylä - Lahti railway connection industrial sector Degree programme Bachelors degree in Logistics Engineering Supervisor(s) Somerla Mikko, Franssila Tommi Assigned by - Abstract There has been a long discussion on the topic of constructing a new rail network from Cen- tral Finland to the capital area. Studies on the topic have been conducted by the govern- mental and local institutions, but most of the information is growing old and obsolete. Therefore, a more modern study on the topic is required. The objective of the present study was to assess the feasibility of the railway connection with as up-to-date information as possible. The aim was to determine the basis and groundwork for a further study on the topic as well as discuss the requirements and appli- cations required in the design and development of a possible future railway connection. The study relied on more recent and industry-based information on the implementation of such a project. This included a thorough search and analysis of publications and other sources in Finnish and European as well as selectively other governmental databases in or- der to compare and assess what was relevant and noteworthy for the study. While search- ing for the information, also the possible future applications had to be taken into consider- ation. -

Waste Sorting Instructions &P Paino Oy, 2000 Kpl, 2/2016 Paino Oy, M &P

WASTE IS BEAUTIFUL tions struc g in rtin te so Household wa 2016 • Asikkala • Myrskylä • Heinola • Orimattila • Hollola • Padasjoki • Kärkölä • Pukkila • Lahti • Sysmä Table of contents Energy waste (combustible waste) 4 Mixed waste 4 Biowaste 5 Paper 5 Carton, packaging waste 6 Glass, packaging waste 6 Metal, packaging waste 7 Plastic, packaging waste 7 Electrical equipment 8 Garden waste 8 Hazardous waste 9 Medicines 9 Furniture and other bulky items 10 Construction and renovation waste 10 Collection points 11 Wate management is everyone’s business The Päijät-Häme region has uniform waste management regulations in force, pertaining to the management of waste generated by households in Asikkala, Heinola, Hollola, Kärkölä, Lahti, Myrskylä, Orimattila, Padasjoki, Pukkila and Sysmä. All residential properties must sort waste at least into energy and mixed waste and they are encouraged to compost biowaste on their own volition. 2 Household wate bins required for residential properties of various sizes Detached houses, semi-detached houses, holiday homes • energy waste bin • mixed waste bin • composter when possible Multi-dwelling units with 3–9 flats • energy waste bin • mixed waste bin • paper bin (in built-up areas) • composter when possible Blocks of flats and terraced houses Waste paper collected free of charge from properties with at least 10 flats in areas with blocks of flats and terraced houses. Properties are responsible for acquiring a paper bin in areas with a local detailed plan in Asikkala, either by themselves or together with -

Lahti-Kovola-Rataosuuden Kulttuurihistoriallisten Kohteiden

Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 LAHTI–KOUVOLA-RATAOSUUDEN KULTTUURIHISTORIALLISTEN KOHTEIDEN INVENTOINTI Roosa Ruotsalainen Lahti–Kouvola-rataosuuden kulttuurihistoriallisten kohteiden inventointi Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 Väylävirasto Helsinki 2021 Kannen kuva: Lepomaan hautausmaan kiviaitaa. Kuva: Roosa Ruotsalainen Verkkojulkaisu pdf (www.vayla.fi) ISSN 2490-0745 ISBN 978-952-317-838-0 Väylävirasto PL 33 00521 HELSINKI Puhelin 0295 34 3000 Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021 3 Roosa Ruotsalainen: Lahti–Kouvola-rataosan kulttuurihistoriallinen inventointi. Väy- lävirasto. Helsinki 2021. Väyläviraston julkaisuja 3/2021. 67 sivua ja 3 liitettä. ISSN 2490- 0745, ISBN 978-952-317-838-0. Asiasanat: rautatiet, inventointi, kulttuuriperintö Tiivistelmä Tässä selvityksessä kartoitettiin Lahden ja Kouvolan välisen radan kulttuurihisto- riallista merkitystä ja selvitettiin radan rakenteiden ja siihen liittyvien rakennusten ja erilaisten kohteiden historiaa. Tavoitteena työssä oli tämän lisäksi kerätä koke- muksia tulevia ratainventointeja varten. Selvitys on jatkoa suoritetuille sisävesi- inventoinneille. Selvitys suoritettiin arkistotutkimuksen ja maastokäyntien avulla. Maastokäynneillä kartoitettiin 70 erilaista kohdetta, kuten asema-alueet, tasoristeyspaikat, taito- rakenteet, vanhat ratapohjat ja sivuradat sekä ratavartijan tupien tontit. Tarkiste- tuista kohteista valittiin 31 kohdetta, joista tehtiin kohdekortit. Selvityksessä valituille kohteille tehtiin arvoluokitus kohdekortteihin. Kohteet arvo- tettiin Väyläviraston arvokohteiden -

Kirje 09 Liite SRP

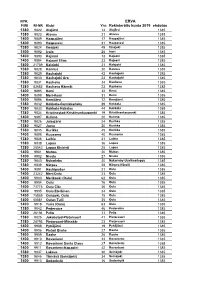

NYK. ERVA PIIRI RI-NR Klubi Yht: Rekisteröity kunta 2019 ehdotus 1380 9822 Alajärvi 14 Alajärvi 1385 1380 9823 Alavus 21 Alavus 1385 1400 9889 Haapajärvi 17 Haapajärvi 1385 1400 9890 Haapavesi 31 Haapavesi 1385 1380 9824 Ilmajoki 49 Ilmajoki 1385 1400 9892 Ivalo 28 Inari 1385 1400 9893 Kajaani 13 Kajaani 1385 1400 9894 Kajaani Elias 33 Kajaani 1385 1400 21739 Kalajoki 21 Kalajoki 1385 1380 9828 Kannus 30 Kannus 1385 1380 9829 Kauhajoki 42 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9830 Kauhajoki Aro 24 Kauhajoki 1385 1380 9831 Kauhava 34 Kauhava 1385 1380 83683 Kauhava Härmät 23 Kauhava 1385 1400 9895 Kemi 32 Kemi 1385 1400 9899 Meri-Kemi 31 Kemi 1385 1400 9896 Kemijärvi 12 Kemijärvi 1385 1380 9832 Kokkola-Gamlakarleby 29 Kokkola 1385 1380 9833 Kokkola-Hakalax 44 Kokkola 1385 1380 9834 Kristinestad-Kristiinankaupunki 19 Kristiinankaupunki 1385 1400 9897 Kuhmo 20 Kuhmo 1385 1380 9826 Jalasjärvi 24 Kurikka 1385 1380 9827 Jurva 20 Kurikka 1385 1380 9835 Kurikka 45 Kurikka 1385 1400 9898 Kuusamo 40 Kuusamo 1385 1380 9836 Laihia 31 Laihia 1385 1380 9838 Lapua 36 Lapua 1385 1380 25542 Lapua Kiviristi 25 Lapua 1385 1400 9901 Muhos 20 Muhos 1385 1400 9902 Nivala 27 Nivala 1385 1380 9840 Nykarleby 40 Nykarleby-Uusikaarlepyy 1385 1380 9839 Närpes 28 Närpes-Närpiö 1385 1400 9891 Haukipudas 21 Oulu 1385 1400 23242 Meri-Oulu 23 Oulu 1385 1400 9900 Merikoski (Oulu) 62 Oulu 1385 1400 9904 Oulu 76 Oulu 1385 1400 73778 Oulu City 36 Oulu 1385 1400 9905 Oulu Eteläinen 34 Oulu 1385 1400 75859 Oulujoki, Oulu 15 Oulu 1385 1400 50881 Oulun Tulli 35 Oulu 1385 1400 9918 Tuira (Oulu) -

Sisulisätilastot 2018

Lahden Seudun Yleisurheilu r.y. Sisulisätilastot 2018 Huom! Juoksulajien käsiajat ilmoitettu lisämainintana vain, jos ne ovat 40 - 200 m matkoilla yli 0,24 s ja 300 m tai sitä pidemmillä matkoilla yli 0,14 s ”parempia” kuin kunkin automaattisella ajanotolla saavutetut tulokset. Tuulilukemat on ilmoitettava pikajuoksuista ja pituussuuntaisista hypyistä 14 v. sarjasta alkaen ylöspäin, muuten kirjattu ”ei tuulilukemaa” -otsikon alle. Sisäratatulokset mainittu, jos ne ovat a.o. urheilijan ulkoratatuloksia paremmat. Tilaston laatinut: Aulis Tiensuu Pahkakatu 4 as 4 15950 LAHTI p. 040 - 5511 030 mailto: [email protected] Tilaston sekä piiriennätystulosten mahdolliset korjaukset ja täydennykset suoraan tekijälle, kiitos 1 POJAT 40 m P 10 6,53 Verneri Marttila 2008 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 21.08. Hip 6,66 Alex Kurkela 2008 Lahti Lahti/R 21.08. Hip 6,69 Jesse Korhonen 2008 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 21.08. Hip P 9 PE 6,3 Ville Suorajärvi 1994Nastolan Naseva Nastola 12.08.2003 6,57 Joska Tommola 1999 Asikkalan Raikas Kuhmoinen16.08.2008 6,55 i Karim Echahid 2001 Lahden Ahkera Espoo/O 06.12.2010 6,55 Oskari Syväranta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 10.08.2018 6,55 Oskari Syväranta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 10.08. so 6,64 -0,5 Lahti/R 08.07. kv 6,63 -0,5 Rasmus Rautavirta 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/R 08.07. kv 6,94 i Ilkka Kallioniemi 2009 Lahden Ahkera Lahti/P 02.04. pm 7,04 Lahti/N 17.05. pk 6,98 Niilo Kemppainen 2009 Nastolan Naseva Iitti/K 17.07. pm 7,07 +1,6 Kouvola 28.07. -

Lahden Seudun Liikennetutkimus 2010

Lahden seudun liikennetutkimus 2010 Lahden seudulla tehtiin keväällä 2010 laaja liikennetutkimus, jossa selvi- Liikennetutkimuksen ovat toteuttaneet tettiin henkilöhaastatteluilla, ajoneuvoliikenteen tutkimuksilla ja liikenne- Uudenmaan ELY-keskus, Lahden kaupunki, laskennoilla seudun asukkaiden liikkumistottumuksia sekä ajoneuvolii- Asikkalan kunta, Hollolan kunta, Nastolan kenteen, jalankulun ja pyöräilyn määrää. Liikennetutkimusalueeseen kunta ja Orimattilan kaupunki sekä Päijät- kuuluivat Asikkala, Hollola, Lahti, Nastola ja Orimattila. Vastaava liikenne- Hämeen liitto maakunnan kehittämis- tutkimus on viimeksi toteutettu Lahden seudulla vuosina 1996 ja 1982. rahoituksella. Lisätietoja liikennetutkimuk- sesta on saatavilla internetissä osoitteessa Seudun asukkaat tekevät yli 500 000 matkaa http://www.paijat-hame.fi/liikennetutkimus päivittäin 1 100 ajon./vrk 63 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden seudulle ja 37 % kulki Kaiken kaikkiaan seudun yli 5-vuotiaat asukkaat seudun läpi tekevät arkisin noin 520 000 matkaa, joista suurin 6 700 ajon./vrk osa on oman kunnan sisäisiä matkoja. Matkalla 49 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden tarkoitetaan siirtymistä paikasta toiseen kävellen seudulle ja 61 % kulki 2 600 ajon./vrk seudun läpi tai jollain kulkuneuvolla, esimerkiksi kotoa kaup- 73 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden paan, kotoa työpaikalle tai kaupasta kotiin. Näi- seudulle ja 27 % kulki seudun läpi 2 500 ajon./vrk den matkojen lisäksi seudun ulkopuolella asuvat 64 % matkoista suuntautui Lahden tekevät matkoja Lahden seudulle ja myös Lahden seudulle