Tribal Identity Dynamics: a Case Study of Us-Haqqanis Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Gun-Running and the Indian North-West Frontier Arnold Keppel

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 Gun-running and the Indian north-west frontier Arnold Keppel Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation London, England: J. Murray, 1911 xiv, 214 p. : folded maps, and plates Includes an index This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GUN-RUNNING AND THE INDIAN NORTH-WEST FRONTIER MULES (,'ROSSING THE I\I.tRBI< IN TIlE PASS OF PASllhli. ~~'UII~~HIJ~SOO, GUN-RUNNING AND THE INDIAN NORTH - WEST FRONTIER BY THE HON. ARNOLD KEPPEL WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATTONS FORT JEIoLALI, MUSCAT. LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. 1911 SIR GEORGE ROOS-ICEPPEL, K .C.I.E. CHIEF COMMISSIONER Oh' TIIE NOR'I'I-1-WEST FRONTIER AND AGENT TO THE OOYERNOR-OENEnAL IN REMEMBRANCE OF A " COLD-MrEATHER " IN PESHAWAR v CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PESHAWAR AND TI-11% ICIIAIDAIl PASS 11. TIIIC ZAKICA ICHRT, AND MOl-IMANII ICXPEDITIONS . 111. TIIE POT,ICY OB' THE AMIR . IV. TI33 AUTUMN CRISIS, 1910 . V. TRIBAL 1tESPONSI~II.ITY VERSUS BANA'L'I(!ISAI. VI. PROM PKSHAWAR TO PAItACTTTNAIl . VII. SOUTITICRN WAZIRTS'I'AX . VIII. THE POTJCP OF SOX-INTERVENTION , IX. A CRUTSli: IN THE I'EHSIAN GULF . X. GUN-RUNNING IN TI~TlC PERSIAN GU1.P XI. -

The Haqqani Network

October 2010 Jeffrey A. Dressler AFGHANISTAN REPORT 6 THE HAQQANI NETWORK FROM PAKISTAN TO AFGHANISTAN INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY of WAR Military A nalysis andEducation for Civilian Leaders Cover photo: Members of an Afghan-international security force pull security on a compound in Waliuddin Bak dis- trict, of Khost province, Afghanistan, Apr. 8, 2010. During the search, the security force captured a Haqqani facilita- tor, responsible for specialized improvised explosive device support and technical expertise for various militant networks. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Mark Salazar/Released) All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2010 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2010 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515, Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jeffrey A. Dressler is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) where he studies security dynamics in southeastern and southern Afghanistan. He previously published the ISW report, Securing Helmand: Understanding and Responding to the Enemy (October 2009). Dressler’s work has drawn praise from members of the Marine Corps and the intelligence community for its understanding of the enemy network in southern Afghanistan and analysis of the military campaign in Helmand province over the past several years. Dressler was invited to Afghanistan in July 2010 to conduct research for General David Petraeus following his assumption of command. -

Understanding Warlordism S Understanding Warlordism G H S

PRIO PAPER Kristian Berg Harpviken Berg Kristian Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) Oslo Institute Research Peace Independent • International • Interdisciplinary Interdisciplinary • • International Independent Warlordism Understanding Areas Southeastern Afghanistan’s from Biographies Three Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW) Design: Studio 7 www.studoisju.no Checkpost south of Ghazni PO Box 9229 Grønland, NO-0134 Oslo, Norway Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) ISBN: 978-82-7288-350-7 city, on the Kabul-Kandahar Visiting Address: Hausmanns gate 7 PO Box 9229 Grønland, NO-0134 Oslo, Norway highway, Aug '94 (Qari Baba’s Visiting Address: Hausmanns gate 7 mujahedin). Photo: K B Harpviken where they operated and the challenges they faced, their personal diverged trajectories in the This period. post-2001 to paper attempts understand why this was so; why did one to be- arms his down man lay come a politician, another for com- capacity place his at the ser- violence manding gov- Karzai new of the vice con- the third while ernment, tinued to the challenge new rulers with armed force? The analysis of these trajectories will provide an insight into the nature of violent warlordism during the formal transition from war to peace and into the period. post-conflict tion and the transitional chal- transitional and the tion par- lenges that followed led the to three men in different direc-elected was a politi- up took Rocketi tions. career, cal liament in 2005, and four active an remained later years player in legal Qari politics. a gover- as briefly served Baba nor but was dethroned to the of position a advisor security and then Tali- the assassinated. -

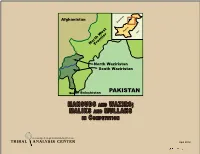

Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition

Afghanistan FGHANISTAN A PAKISTAN INIDA NorthFrontier West North Waziristan South Waziristan Balochistan PAKISTAN MAHSUDS AND WAZIRS; MALIKS AND MULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER April 2012 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition M AHSUDS AND W AZIRS ; M ALIKS AND M ULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition No patchwork scheme—and all our present recent schemes...are mere patchwork— will settle the Waziristan problem. Not until the military steam-roller has passed over the country from end to end, will there be peace. But I do not want to be the person to start that machine. Lord Curzon, Britain’s viceroy of India The great drawback to progress in Afghanistan has been those men who, under the pretense of religion, have taught things which were entirely contrary to the teachings of Mohammad, and that, being the false leaders of the religion. The sooner they are got rid of, the better. Amir Abd al-Rahman (Kabul’s Iron Amir) The Pashtun tribes have individual “personality” characteristics and this is a factor more commonly seen within the independent tribes – and their sub-tribes – than in the large tribal “confederations” located in southern Afghanistan, the Durranis and Ghilzai tribes that have developed in- termarried leadership clans and have more in common than those unaffiliated, independent tribes. Isolated and surrounded by larger, and probably later arriving migrating Pashtun tribes and restricted to poorer land, the Mahsud tribe of the Wazirs evolved into a nearly unique “tribal culture.” For context, it is useful to review the overarching genealogy of the Pashtuns. -

Bayazid Ansari and Roushaniya Movement: a Conservative Cult Or a Nationalist Endeavor?

Himayatullah Yaqubi BAYAZID ANSARI AND ROUSHANIYA MOVEMENT: A CONSERVATIVE CULT OR A NATIONALIST ENDEAVOR? This paper deals with the emergence of Bayazid Ansari and his Roushaniya Movement in the middle of the 16th century in the north-western Pakhtun borderland. The purpose of the paper is to make comprehensive analyses of whether the movement was a militant cult or a struggle for the unification of all the Pakhtun tribes? The movement initially adopted an anti- Mughal stance but side by side it brought stratifications and divisions in the society. While taking a relatively progressive and nationalist stance, a number of historians often overlooked some of its conservative and militant aspects. Particularly the religious ideas of Bayazid Ansari are to be analyzed for ascertaining that whether the movement was nationalist in nature and contents or otherwise? The political and Sufi orientation of Bayazid was different from the established orders prevailing at that time among the Pakhtuns. An attempt would be made in the paper to ascertain as how much support he extracted from different tribes in the Pakhtun region. From the time of Mughal Emperor Babur down to Aurangzeb, the whole of the trans-Indus Frontier region, including the plain and the hilly tracts was beyond the effective control of the Mughal authority. The most these rulers, including Sher Shah, himself a Ghalji, did was no more than to secure the hilly passes for transportation. However, the Mughal rulers regarded the area not independent but subordinate to their imperial authority. In the geographical distribution, generally the area lay under the suzerainty of the Governor at Kabul, which was regarded a province of the Mughal Empire. -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879. -

Yusufzai Tribe Aka: Yousefzai

Program for Culture and Conflict Studies YUSUFZAI TRIBE AKA: YOUSEFZAI The Program for Culture & Conflict Studies Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA Material contained herein is made available for the purpose of peer review and discussion and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. PRIMARY LOCATION The Yusufzai live north of Peshawar in Swat, Bunar1 and the Mardan2 and Malakand districts of the North-West Frontier Province.3 KEY TERRAIN FEATURES Valleys: Indus, Swat, Panjkora Plains: Yusufzai Plains Mountains: Kuh-e Sefid Rivers: Indus, Swat, Panjkora Dams: Maulana Dam, Zeran Dam, Kot Ragha Dam Malikhel The Kurram Agency is divided into three sub-divisions: Upper, Lower, and Central Kurram. The upper and lower divisions have long been administered and are subject to the Frontier Crimes Regulation, Kohat Pact, and tribal law. The central division, however, is still largely inaccessible, and development in this region lags behind the other two. Though each of the three divisions are headed by Assistant Political Agents, administration of Central Kurram is headed by tribal elders.4 WEATHER Average temperatures in the Peshawar valley range from the mid- to upper-60s in the winter and between mid-90s to 105 in the summer. It averages about 18 inches of rain per year with the majority falling between February and April. RELIGION/SECT The Yusufzai are of the Sunni Sect of Islam. FEUDS The Yusufzai have a history of fueding with the Mohmand tribe primarily over land rights.5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION The Yusufzai population was estimated at 500,000 in 1965.6 They have special recognition for two of their tribal leaders: Wali of Swat and the Mir of Dir.7 These are ancestors of Yusufzai tribesman who led the tribe when it first conquered the 1 Arnold Fletcher, Afghanistan Highway of Conquest, (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1965), 296. -

Counterinsurgency in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY institution that helps improve policy and POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY decisionmaking through research and SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY analysis. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND Support RAND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in Pakistan Seth G. Jones, C. Christine Fair NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Project supported by a RAND Investment in People and Ideas This monograph results from the RAND Corporation’s Investment in People and Ideas program. -

100-Incidents-Of-Humanitarian-Harm

Report by Esther Cann and Katherine Harrison Editor Katherine Harrison With contributions by Nerina Cevra, Coordinator, Survivor Rights & Victim Assistance, AOAV; and Henry Dodd, Research Intern, AOAV. Copyright © Action on Armed Violence, March 2011 With thanks to Suhair Abdi, Ailynne Benito, Mike Boddington, Roos Boer, John Borrie, Maya Brehm, Dr. Réginald Moreels, Richard Moyes, Thomas Nash, Kerry Smith, Verity Smith, Miriam Struyk, and Sebastian Taylor. Photographic material Bobby Benito/Bangsamoro Centre for Justpeace, Free Burma Rangers, Abdul Majeed Goraya/IRIN, ISM Palestine/ Wikimedia Commons, Rachel Kabejja/The Daily Monitor, Jason Motlagh/Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Avi Ohayon/Wikimedia Commons, Mark Pearson/ShelterBox UK, and Muhammad Sabah/B’Tselem. Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome. Research and publication funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record of this report is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-0-9568521-0-6 Design Kieran Gardner Printing FM Print 100 InCIDEnts of HuManItaRIan HaRM Published in March 2011 by: Action on Armed Violence (Landmine Action) 5th Floor, Epworth House, 25 City Road, London, EC1Y 1AA T +44 (0) 20 7256 9500 F +44 (0) 20 7256 9311 Landmine Action is a company limited by guarantee. Registered in England and Wales no. 3895803. Contents Introduction 6 Executive summary 8 Incident profile guide 10 Incident profiles 1–100 11 Health impacts 17 Children and explosive weapons 28 Damage to infrastructure, property, and services 36 Displacement and explosive weapons 50 Harm caused by explosive remnants of war 61 Harm from explosions in stockpiles 69 Victim assistance 80 Counting explosive weapons casualties 89 annex: the research process 101 sources, incidents 1–100 102 The graffiti reads: “This market was destroyed by the Americans and the Saudi Arabians. -

Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 3-24-1965 Kabul Times (March 24, 1965, vol. 4, no. 3) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (March 24, 1965, vol. 4, no. 3)" (1965). Kabul Times. 847. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/847 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '. , ~._.- . ~UL, .- MARCH 23,J9li5, , ~~ f'AGIC 4 .:....:..._--:-~~ TIMI8~.:"'"""''''';':''''''~''''': .. __ . ~_ .' :=:~-:.,---"'-"'~~.'~.'~--:'~"':'::--'~L":'-'-~ -I»" :b",,;'. Ra~r Nine on ·AT:~~NE;·~cn~EMA··.-· . '. Chen Yi s Speech 8e1YGe¥,c 89IIQY .es~I_ ~ ,:'" - 'c- ".-~ 0 0 PAB!< ~ To ,0 . (~~.~i). -: Smooth'Landing. PfVoSJ(~~d.·. ~~r,~eif~,~ath !Fr~J~~~'~~~1IA~h~ZO h~,in ~'~17ch~~:~e ' .. ' .'.' ' ..: .'.. MOSCOW, Mardf:J3; (~).-~ . To 'MOOn ·Crater.,. ~~~~-Wlth.; D~ ..trans~- . _ . .natianaI J~ce, w~ U.N.:' . NEL. '.FaveJ.. Bel~v aDd ~t;oiCelcmel: AJ~ ,~~v ". -'.. '.. tion .. ... .. .' 'pa='::~:g~~~ visi~:.'T¥r C~~·1JL·~eli:o~.J!raJS~ their ~lp ':V~ocl u, c~~~~~::: ~i~Y}b~~.m.:1ndian timL . MajestieS the King, and Queen. lias !aIlded ~ey ar:e~ffflrnc.~~ ~care iD·-a ,~ '. ~aft is :~:n~«tPath to ~ ~:! :.' :. paid to China five ~onthS ago, tlie TaSs. '8peelaJ eoniESpoDAlent·~.troJD.Balk~.~ its inteI1aed target. on tlie moon'-. At '2,.~.6 P;ID. .RI,ISS .8n:' tUm. -

How Opium Profits the Taliban / Gretchen Peters

S How Opium RK Profits the Taliban Gretchen Peters EW AC UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PE The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect views of the United States Institute of Peace. UNITED STATE S IN S TIT U TE OF PEACE 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 62. First published August 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Peters, Gretchen. How opium profits the Taliban / Gretchen Peters. p. cm. — (Peaceworks no. 62.) ISBN 978-1-60127-032-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Opium trade—Afghanistan. 2. Drug traffic—Afghanistan. 3. Taliban. 4. Afghanistan— Economic conditions. 5. Afghanistan—Politics and government—2001. 6. United States— Foreign relations—Afghanistan. 7. Afghanistan—Foreign relations—United States. I. Title. HV5840.A53P48 2009 363.4509581—dc22 2009027307 Contents Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. A Brief History 7 3. The Neo-Taliban 17 4. Key Challenges 23 5. Conclusion 33 About the Author 37 1 Summary In Afghanistan’s poppy-rich south and southwest, a raging insurgency intersects a thriving opium trade. This study examines how the Taliban profit from narcotics, probes how traffick- ers influence the strategic goals of the insurgency, and considers the extent to which narcotics are changing the nature of the insurgency itself. With thousands more U.S. troops deploying to Afghanistan, joined by hundreds of civilian partners as part of Washington’s reshaped strategy toward the region, understanding the nexus between traffickers and the Taliban could help build strategies to weaken the insurgents and to extend governance.