Stratification Among Pathans of Farrukhabad Distt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: a Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier During the First World War

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: A Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier during the First World War Dr. Salman Bangash. “History is certainly being made in this corridor…and I am sure a great deal more history is going to be made there in the near future - perhaps in a rather unpleasant way, but anyway in an important way.” (Arnold J. Toynbee )1 Introduction No region of the British Empire afforded more grandeur, influence, power, status and prestige then India. The British prominence in India was unique and incomparable. For this very reason the security and safety of India became the prime objective of British Imperial foreign policy in India. India was the symbol of appealing, thriving, profitable and advantageous British Imperial greatness. Closely interlinked with the question of the imperial defence of India was the tribal belt2 or tribal areas in the North-West Frontier region inhabitant by Pashtun ethnic groups. The area was defined topographically as a strategic zone of defence, which had substantial geo-political and geo-strategic significance for the British rule in India. Tribal areas posed a complicated and multifaceted defence problem for the British in India during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Peace, stability and effective control in this sensitive area was vital and indispensable for the security and defence of India. Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 1 Arnold J. Toynbee, „Impressions of Afghanistan and Pakistan‟s North-West Frontier: In Relation to the Communist World,‟International Affairs, 37, No. 2 (April 1961), pp. -

AFRIDI Colonel Monawar Khan

2019 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER A CONCISE BIOGRAPHY OF: COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI A concise biography of Colonel Monawar Khan AFRIDI, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M. & H., who was an officer in the Indian Medical Service between 1924 and 1947; and a distinguished physician in Pakistan after the Second World War. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2019) 1 December 2019 [COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI] A Concise Biography of Colonel M. K. AFRIDI Version: 3_1 This edition dated: 1 December 2019 ISBN: Not yet allocated. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. (copyright held by author) Published privately by: The Author – Publishing as: www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk 1 1 December 2019 [COLONEL M. K. AFRIDI] Colonel Monawar Khan AFRIDI, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P., D.T.M. & H., Indian Medical Service. For an Army to fight a campaign successfully, many different aspects of military activity need to be in place. The soldiers who do the actual fighting need to be properly trained, equipped, supplied, and importantly for the individual soldiers, they need to know that in the event of them being wounded (which is more likely than not), they will receive the best medical treatment possible. In South East Asia, more soldiers fell ill than were wounded in battle, and this fact severely affected the ability of the Army to sustain any unit in the front line for any significant period. -

Gun-Running and the Indian North-West Frontier Arnold Keppel

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 Gun-running and the Indian north-west frontier Arnold Keppel Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation London, England: J. Murray, 1911 xiv, 214 p. : folded maps, and plates Includes an index This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GUN-RUNNING AND THE INDIAN NORTH-WEST FRONTIER MULES (,'ROSSING THE I\I.tRBI< IN TIlE PASS OF PASllhli. ~~'UII~~HIJ~SOO, GUN-RUNNING AND THE INDIAN NORTH - WEST FRONTIER BY THE HON. ARNOLD KEPPEL WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATTONS FORT JEIoLALI, MUSCAT. LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W. 1911 SIR GEORGE ROOS-ICEPPEL, K .C.I.E. CHIEF COMMISSIONER Oh' TIIE NOR'I'I-1-WEST FRONTIER AND AGENT TO THE OOYERNOR-OENEnAL IN REMEMBRANCE OF A " COLD-MrEATHER " IN PESHAWAR v CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PESHAWAR AND TI-11% ICIIAIDAIl PASS 11. TIIIC ZAKICA ICHRT, AND MOl-IMANII ICXPEDITIONS . 111. TIIE POT,ICY OB' THE AMIR . IV. TI33 AUTUMN CRISIS, 1910 . V. TRIBAL 1tESPONSI~II.ITY VERSUS BANA'L'I(!ISAI. VI. PROM PKSHAWAR TO PAItACTTTNAIl . VII. SOUTITICRN WAZIRTS'I'AX . VIII. THE POTJCP OF SOX-INTERVENTION , IX. A CRUTSli: IN THE I'EHSIAN GULF . X. GUN-RUNNING IN TI~TlC PERSIAN GU1.P XI. -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

M/S. SKYANSH FILMS PRODUCTION 25073

M/s. SKYANSH FILMS PRODUCTION M/s. SURYA STUTI ENTERTAINMENT 25073 - 01/03/2016 25081 - 01/03/2016 406, 407, 408, Sanmahu Complex, 4th Floor, Opp. Poona Club, House No.227, Village Bhargwan, Shahjahanpur, Bund Garden Road, Pune, 242 001 U.P. 411 001 Maharashtra SURYA KANT VERMA SURESH KESHAVRAO YADAV 9892983731 9822619772 M/s. B V M FILMS M/s. YADUVANSHI FILMS PRODUCTION HOUSE 25074 - 01/03/2016 25082 - 01/03/2016 L 503, Anand Vihar CHS, Opp. Windermere, Oshiwara, Andheri 5/131, Jankipuram, Sector-H, Lucknow, (W), Mumbai, 226 021 U.P. 400 053 Maharashtra RAMESH KUMAR YADAV MANOJ BINDAL, SANTOSH BINDAL, OM PRAKASH BINDAL 9839384024 9811045118 M/s. SHIVAADYA FILM PRODUCTION PVT. LTD. M/s. MAHAKALI ENTERTAINMENT WORLD 25075 - 01/03/2016 25083 - 01/03/2016 L 14/516, Bldg. No.1, 5th Floor, Kamdhenu Apna Ghar Unit Naya Salempur-1, Salempur, Tehsil: Lakhimpur, Dist: Kheri, No.14, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri (W), Mumbai, 262 701 U.P. 400 053 Maharashtra AJAY RASTOGI SANGITA ANAND, SABITA MUNKA 9598979590 7710891401 M/s. ADINATH ENTERTAINMENT & FILM PRODUCTION M/s. FAIZAN-A-RAZA FILM PRODUCTION 25076 - 01/03/2016 25084 - 01/03/2016 L 9/A, Saryu Vihar, Basant Vihar, Kamla Nagar, Agra, 35, Hivet Road, Aminabad, Tehsil & Dist: Lucknow, 282 002 U.P. 226 018 U.P. VIMAL KUMAR JAIN ABDUL AZIZ SIDDIQUE 8445611111 9451503544, 9335218406 M/s. SHIV OM PRODUCTION M/s. SHREE SAI FILMS ENTERTAINMENT HOUSE 25077 - 01/03/2016 25085 - 01/03/2016 Kalpataru Aura, Building No.Onyx 3G,Flat No.111, L.B.S. Marg, Plot No.21/A, Netaji Nagar, Old Pardi Naka, Near Prathmesh Opp. -

A Case Study of the Bazaar Valley Expedition in Khyber Agency 1908

Journal of Law and Society Law College Vol. 40, No. 55 & 56 University of Peshawar January & July, 2010 issues THE BRITISH MILITARY EXPEDITIONS IN THE TRIBAL AREAS: A CASE STUDY OF THE BAZAAR VALLEY EXPEDITION IN KHYBER AGENCY 1908 Javed Iqbal*, Salman Bangash**1, Introduction In 1897, the British had to face a formidable rising on the North West Frontier, which they claim was mainly caused by the activities of ‘Mullahs of an extremely ignorant type’ who dominated the tribal belt, supported by many disciples who met at the country shrines and were centre to “all intrigues and evils”, inciting the tribesmen constantly against the British. This Uprising spread over the whole of the tribal belt and it also affected the Khyber Agency which was the nearest tribal agency to Peshawar and had great importance due to the location of the Khyber Pass which was the easiest and the shortest route to Afghanistan; a country that had a big role in shaping events in the tribal areas on the North Western Frontier of British Indian Empire. The Khyber Pass remained closed for traffic throughout the troubled years of 1897 and 1898. The Pass was reopened for caravan traffic on March 7, 1898 but the rising highlighted the importance of the Khyber Pass as the chief line of communication and trade route. The British realized that they had to give due consideration to the maintenance of the Khyber Pass for safe communication and trade in any future reconstruction of the Frontier policy. One important offshoot of the Frontier Uprising was the Tirah Valley expedition during which the British tried to punish those Afridi tribes who had been responsible for the mischief. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

'As If Hell Fell On

‘a s if h ell fel l on m e’ THE HUmAn rIgHTS CrISIS In norTHWEST PAKISTAn amnesty international is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal Declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. amnesty international Publications first published in 2010 by amnesty international Publications international secretariat Peter Benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0Dw united kingdom www.amnesty.org © amnesty international Publications 2010 index: asa 33/004/2010 original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Front and back cover photo s: families flee fighting between the Taleban and Pakistani government forces in the maidan region of lower Dir, northwest -

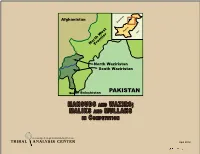

Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition

Afghanistan FGHANISTAN A PAKISTAN INIDA NorthFrontier West North Waziristan South Waziristan Balochistan PAKISTAN MAHSUDS AND WAZIRS; MALIKS AND MULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER April 2012 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition M AHSUDS AND W AZIRS ; M ALIKS AND M ULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition No patchwork scheme—and all our present recent schemes...are mere patchwork— will settle the Waziristan problem. Not until the military steam-roller has passed over the country from end to end, will there be peace. But I do not want to be the person to start that machine. Lord Curzon, Britain’s viceroy of India The great drawback to progress in Afghanistan has been those men who, under the pretense of religion, have taught things which were entirely contrary to the teachings of Mohammad, and that, being the false leaders of the religion. The sooner they are got rid of, the better. Amir Abd al-Rahman (Kabul’s Iron Amir) The Pashtun tribes have individual “personality” characteristics and this is a factor more commonly seen within the independent tribes – and their sub-tribes – than in the large tribal “confederations” located in southern Afghanistan, the Durranis and Ghilzai tribes that have developed in- termarried leadership clans and have more in common than those unaffiliated, independent tribes. Isolated and surrounded by larger, and probably later arriving migrating Pashtun tribes and restricted to poorer land, the Mahsud tribe of the Wazirs evolved into a nearly unique “tribal culture.” For context, it is useful to review the overarching genealogy of the Pashtuns. -

UNIT 16 MUSLIM SOCIAL ORGANISATION Muslim Social Organisation

UNIT 16 MUSLIM SOCIAL ORGANISATION Muslim Social Organisation Structure 16.0 Objectives 16.1 Introduction 16.2 Emergence of Islam and Muslim Community in India 16.3 Tenets of Islam: View on Social Equality 16.4 Aspects of Social Organisation 16.4.1 Social Divisions among Muslims 16.4.2 Caste and Kin Relationships 16.4.3 Social Control 16.4.4 Family, Marriage and Inheritance 16.4.5 Life Cycle Rituals arid Festivals 16.5 External Influence on Muslim Social Practices 16.6 Let Us Sum Up 16.7 Keywords 16.8 Further Reading 16.9 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 16.0 OBJECTIVES On going through this unit you should be able to z describe briefly the emergence of Islam and Muslim community in India z list and describe the basic tenets of Islam with special reference to its views on social equality z explain the social divisions among the Muslims z describe the processes involved in the maintenance of social control in the Islamic community z describe the main features of Muslim marriage, family and systems of inheritance z list the main festivals celebrated by the Muslims z indicate some of the external influences on Muslim social practices. 16.1 INTRODUCTION In the previous unit we examined the various facets of Hindu Social Organisation. In this unit we are going to look at some important aspects of Muslim social organisation. We begin our examination with an introductory note on the emergence of Islam and the Muslim community in India. We will proceed to describe the central tenets of Islam, elaborating the view of Islam on social equality, in a little more detail. -

Bayazid Ansari and Roushaniya Movement: a Conservative Cult Or a Nationalist Endeavor?

Himayatullah Yaqubi BAYAZID ANSARI AND ROUSHANIYA MOVEMENT: A CONSERVATIVE CULT OR A NATIONALIST ENDEAVOR? This paper deals with the emergence of Bayazid Ansari and his Roushaniya Movement in the middle of the 16th century in the north-western Pakhtun borderland. The purpose of the paper is to make comprehensive analyses of whether the movement was a militant cult or a struggle for the unification of all the Pakhtun tribes? The movement initially adopted an anti- Mughal stance but side by side it brought stratifications and divisions in the society. While taking a relatively progressive and nationalist stance, a number of historians often overlooked some of its conservative and militant aspects. Particularly the religious ideas of Bayazid Ansari are to be analyzed for ascertaining that whether the movement was nationalist in nature and contents or otherwise? The political and Sufi orientation of Bayazid was different from the established orders prevailing at that time among the Pakhtuns. An attempt would be made in the paper to ascertain as how much support he extracted from different tribes in the Pakhtun region. From the time of Mughal Emperor Babur down to Aurangzeb, the whole of the trans-Indus Frontier region, including the plain and the hilly tracts was beyond the effective control of the Mughal authority. The most these rulers, including Sher Shah, himself a Ghalji, did was no more than to secure the hilly passes for transportation. However, the Mughal rulers regarded the area not independent but subordinate to their imperial authority. In the geographical distribution, generally the area lay under the suzerainty of the Governor at Kabul, which was regarded a province of the Mughal Empire.