View / Open Chen Oregon 0171N 10747.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presseheft S

Sommer ’04 Ein Film von Stefan Krohmer nach einem Drehbuch von Daniel Nocke mit Martina Gedeck, Robert Seeliger, Peter Davor, Svea Lohde, Lucas Kotaranin Eine Ö Filmproduktion von Katrin Schlösser und Frank Löprich P R E S S E H E F T KINOSTART: 19. OKTOBER 2006 Pressematerial: www.alamodefilm.de Gefördert von der FilmFörderung Hamburg GmbH Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Schlei Ostsee GmbH Pressekontakt: Verleih: Produktion: ZOOMMEDIENFABRIK GmbH Alamode Film Ö Filmproduktion Kerstin Hamm Nymphenburger Str. 36 Langhansstraße 86 Schillerstrasse 94 80335 München 13086 Berlin 10625 Berlin 0 89/17 99 92 10 0 30/44 67 26 0 030/31 80 26 74 0 89/17 99 92 13 0 30/44 67 26 26 030/31 50 68 58 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] INHALT Besetzung 3 Stab 4 Kurzinhalt 5 Langinhalt 5 Pressenotiz 6 Statement von Stefan Krohmer und Daniel Nocke 7 Produktionsnotiz von Katrin Schlösser, Ö Filmproduktion 7 Interview mit Stefan Krohmer 8 Viten Martina Gedeck 9 Robert Seeliger 10 Peter Davor 11 Svea Lohde 12 Lucas Kotaranin 12 Stefan Krohmer 13 Daniel Nocke 14 Patrick Orth 15 Weitere Informationen 16 Die Schlei-Ostsee-Region und die Schlei Ostsee GmbH 17 2 BESETZUNG Martina Gedeck Miriam Peter Davor André Robert Seeliger Bill Svea Lohde Livia Lucas Kotaranin Nils Nicole Marischka Grietje Gabor Altorgay Daniel Michael Benthin Arzt 3 STAB Regie Stefan Krohmer Drehbuch Daniel Nocke Produktion Ö Filmproduktion GmbH Produzentin Katrin Schlösser Redaktion Sabine Holtgreve (SWR) Bettina Reitz (BR) Barbara Buhl (WDR) Georg Steinert (ARTE) Kamera Patrick Orth Licht Theo Lustig Ton Steffen Graubaum Ausstattung Silke Fischer,Volko Kamensky Kostüm Silke Sommer Maske Liliana Müller Casting Nina Haun Schnitt Gisela Zick Sounddesign Tobias Peper Mischton Stephan Konken 4 KURZINHALT Die augenscheinlich glückliche MIRIAM (Martina Gedeck) verbringt mit ihrem Lebensgefährten ANDRE (Peter Davor), ihrem 15-jährigen Sohn NILS (Lukas Kotaranin), sowie dessen 12-jähriger Freundin LIVIA (Svea Lohde) ihre Sommerferien an der schleswig-holsteinischen Ostseeküste. -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Bulletin of the GHI Washington

Bulletin of the GHI Washington Issue 43 Fall 2008 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. TERRORISM IN GERMANY: THE BAADER-MEINHOF PHENOMENON Lecture delivered at the GHI, June 5, 2008 Stefan Aust Editor-in-Chief, Der Spiegel, 1994–2008 Recently on Route 73 in Germany, between Stade und Cuxhaven, my phone rang. On the other end of the line was Thilo Thielke, SPIEGEL correspondent in Africa. He was calling on his satellite phone from Dar- fur. For two weeks he had been traveling with rebels in the back of a pick-up truck, between machine guns and Kalashnikovs. He took some- thing to read along for the long evenings: Moby Dick. He asked me: “How was that again with the code names? Who was Captain Ahab?” “Andreas Baader, of course,” I said and quoted Gudrun Ensslin from a letter to Ulrike Meinhof: “Ahab makes a great impression on his first appearance in Moby Dick . And if either by birth or by circumstance something pathological was at work deep in his nature, this did not detract from his dramatic character. For tragic greatness always derives from a morbid break with health, you can be sure of that.” “And the others?” the man from Africa asked, “Who was Starbuck?” At that time, that was not a coffee company—also named after Moby Dick—but the code name of Holger Meins. -

Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict

FRINGE REPORT FRINGE REPORT www.fringereport.com Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict: Springtime for Baader-Meinhof London - MacOwan Theatre - March 05 21-24, 29-31 March 05. 19:30 (22:30) MacOwan Theatre, Logan Place, W8 6QN Box Office 020 8834 0500 LAMDA Baader-Meinhof.com Black Hands / Dead Section is violent political drama about the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It runs for 3 hours in 2 acts with a 15 minute interval. There is a cast of 30 (18M, 12F). The Baader-Meinhof Gang rose during West Germany's years of fashionable middle-class student anarchy (1968-77). Intellectuals supported their politics - the Palestinian cause, anti-US bases in Germany, anti-Vietnam War. Popularity dwindled as they moved to bank robbery, kidnap and extortion. The play covers their rise and fall. It's based on a tight matrix of facts: http://www.fringereport.com/0503blackhandsdeadsection.shtml (1 of 7)11/20/2006 9:31:37 AM FRINGE REPORT Demonstrating student Benno Ohnesorg is shot dead by police (Berlin 2 June, 1967). Andreas Baader and lover Gudrun Ensslin firebomb Frankfurt's Kaufhaus Schneider department store (1968). Ulrike Meinhof springs them from jail (1970). They form the Red Army Faction aka Baader-Meinhof Gang. Key members - Baader, Meinhof, Ensslin, Jan- Carl Raspe, Holger Meins - are jailed (1972). Meins dies by hunger strike (1974). The rest commit suicide: Meinhof (1976), Baader, Ensslin, Raspe (18 October 1977). The play's own history sounds awful. Drama school LAMDA commissioned it as a piece of new writing (two words guaranteed to chill the blood) - for 30 graduating actors. -

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, A

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, a young man, has decided to follow instructions intended for someone else, without knowing where they will take him. Something else he does not know is that Gerard Dorez, a cop on a knife-edge, is tailing him. When he reaches his destination, Sebastian falls into a degenerate, clandestine world of mental chaos behind closed doors in which men gamble on the lives of others men. 2. Title: 12 Angry Men ISBN: 5050070005172 Adapted from Reginald Rose's television play, this film marked the directorial debut of Sidney Lumet. At the end of a murder trial in New York City, the 12 jurors retire to consider their verdict. The man in the dock is a young Puerto Rican accused of killing his father, and eleven of the jurors do not hesitate in finding him guilty. However, one of the jurors (Henry Fonda), reluctant to send the youngster to his death without any debate, returns a vote of not guilty. From this single event, the jurors begin to re-evaluate the case, as they look at the murder - and themselves - in a fresh light. 3. Title: 12:08 East of Bucharest ISBN: n/a 12:08pm on the 22 December 1989 was the exact time of Ceausescu's fall from power in Romania. Sixteen years on, a provincial TV talk show decides to commemorate the event by asking local heroes to reminisce about their own contributions to the revolution. But securing suitable guests proves an unexpected challenge and the producer is left with two less than ideal participants - a drink addled history teacher and a retired and lonely sometime-Santa Claus grateful for the company. -

September 2019 Dreharbeiten in Wuppertal Für Kino- Und TV

Filmstadt Wuppertal _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Stand: September 2019 Dreharbeiten in Wuppertal für Kino- und TV- Produktionen und Dokumentarfilme The Flying Train (1902) Das Abenteuer eines Journalisten (1914) mit Ludwig Trautmann, R.: Harry Piel (Kinokop-Film) Der Schritt vom Weg (1939) mit Marianne Hoppe, Karl Ludwig Diehl, Elisabeth Flickenschild, R.: Gustav Gründgens (Terra Filmkunst) Madonna in Ketten (1949) mit Elisabeth Flickenschild, Lotte Koche, Willi Millowitsch, R.: Gerhard Lamprecht Inge entdeckt eine Stadt (1954) mit Horst Tappert, R.: Erni und Gero Priemel La Valse du Gorille (1959) mit Charles Vanel, Roger Hanin, Jess Hahn, René Havard, R.: Bernard Borderie Die Wupper (1967) Fernsehfilm mit Ilde Overhoff, Horst-Dieter Sievers, Peter Danzeisen, R.: Kurt Wilhelm, Hans Bauer Acht Stunden sind kein Tag (1972) mit Gottfried John, Hanna Schygulla, Luise Ullrich, Werner Finck; R.+D.:Rainer Werner Fassbinder, P.: Peter Märthesheimer (WDR, 5-teilige Fernsehserie) Alice in den Städten (1973) mit Yella Rottländer, Rüdiger Vogler, Lisa Kreuzer, R.: Wim Wenders (Filmverlag der Autoren/ WDR) Zündschnüre (1974) mit Michael Olbrich, Bettina Porsch, Thomas Visser, Kurt Funk, Tilli Breidenbach, R.: Reinhard Hauff (WDR) Stellenweise Glatteis (1975) mit Günther Lamprecht, Ortrud Beginnen, Giuseppe Coniglio, R.: Wolfgang Petersen Der starke Ferdinand (1976) mit Heinz Schubert, Vérénice Rudolph, Joachim -

Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 44 Issue 1 Article 11 June 2020 Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018; Christina Gerhardt, Marco Abel, ed. Celluloid Revolt: German Screen Cultures and the Long 1968. Camden House, 2019. Svea Braeunert University of Cincinnati, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Cultural History Commons, German Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Braeunert, Svea () "Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018; Christina Gerhardt, Marco Abel, ed. Celluloid Revolt: German Screen Cultures and the Long 1968. Camden House, 2019.," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 1, Article 11. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.2143 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018; Christina Gerhardt, Marco Abel, ed. Celluloid Revolt: German Screen Cultures and the Long 1968. Camden House, 2019. Abstract Review of Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018, xii + 307 pp. and Christina Gerhardt, Marco Abel, ed. -

Niemals Wie Die Eltern Tergrundkämpferin Der RAF, Zur Gesuchten Terroristin Wurde

Deutschland Spannend, dramaturgisch dicht, durch- aus selbstkritisch und gut geschrieben er- ZEITGESCHICHTE zählt die heute 51-jährige Margrit Schiller von jenem Jahrzehnt ihrer Jugend, in dem sie von der braven Bürgerstochter zur Un- Niemals wie die Eltern tergrundkämpferin der RAF, zur gesuchten Terroristin wurde. Es ist auch ein typisch Margrit Schiller, in den Siebzigern Mitglied der RAF, hat ihre deutsches Drama von der ewigen Suche nach Wahrheit und Identität, vom schwär- Autobiografie geschrieben. Überraschend merischen Idealismus, der in der Katastro- packend erzählt sie ihre tragische Guerrilla-Geschichte. phe von Lüge und Gewalt endet. Ebenso wie der zeitliche Abstand der rst durch die Begegnung mit An- fern ist. War da was, und was war es ei- Jahre mag die geografische Distanz zum dreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin und gentlich? Ort des Geschehens geholfen haben, sich EUlrike Meinhof wurde der jungen Margrit Schiller, von 1971 bis 1979 Mit- der Vergangenheit zu nähern: 1985 ging sie Frau glasklar: „Ich war mein Leben lang glied der RAF, weiß es genau. Dennoch nach Kuba, heiratete einen Kubaner und belogen worden.“ Margrit Schiller, da- brauchte sie, von alten Freunden und Ge- lebt heute mit ihren beiden Kindern in mals 22 Jahre alt, Psychologiestudentin nossen immer wieder gebremst und ver- Montevideo, der Hauptstadt Uruguays. und aktives Mitglied des „Sozialistischen unsichert, viele Jahre, um ihren „Lebens- Zudem: Margrit Schiller war, obwohl sie Patientenkollektivs“ (SPK), hatte die bericht aus der RAF“ unter dem Titel „Es von Anfang an mit dem Gründungskern der Gründertruppe der „Roten Armee Frak- war ein harter Kampf um meine Erinne- RAF zusammentraf, eine Randfigur. Das tion“ (RAF) mehrere Wochen lang in ih- rung“ tatsächlich zu veröffentlichen**. -

Presse Zum Stammheimer Prozess

Top of theweek Terrorist Holger Meins: On hls deathbed after a hunger strike Ford: Summoned from dinner to consult on the Mayaguez Marines were landed to snatch the sailors from their The Baader-Meinhof Gang Pa- 8 captors and an American warship towed their merchant- This week in a specially constructed $5 miliion concrete man to safety. But the Mayaguez affair had far broader fortress billed as "terror-proof," Germany will begin its most ramifications. Its underlying theme was geopolitical, a celebrated court proceeding since Nuremberg-the trial of demonstration of U.S. power and purpose to a world that a band of politicai terrorists known as the Baader-Meinhof had begun to doubt both in the wake of the recent debacles gang. Anthony Collings and Alan Field reported for in Indochina. And despite some sobering morning-after Susan Fraker's story on the urban desperados. In a questions, the over-all success of the operation left the companion piece, Daniel Chu profiles terrorist leader Ford Administration almost giddy with euphoria. With files Ulrike Meinhof and in the back-page interview Edward from Bruce van Voorst, Thornas M. DeFrank, Lloyd H. Behr talks with an earlier revolutionary, Daniel Cohn- Norrnan, Henry W. Hubbard, Paul Brinkley-Rogers, Bendit, leader of the 1968 French student uprising. (Cover Bernard Krisher and others, Peter Goldman, Milton R. photos by Mihaly Moldvay-SternIBlack Star, AP, and dpa. Benjamin and Kirn Willenson describe the Mayaguez Mezzotint by Martin J. Weber.) drama and related events last week in Indochina. Galloping Toward Chaos? Page 12 The World of Computers Paga 36 Economic doomsayers are having a field day in Britain- In the last three decades, the use of computers has and with good reason. -

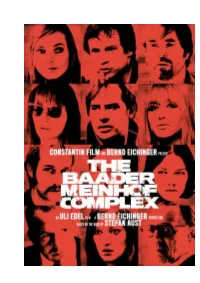

Der Bader-Meinhof Komplex

CONSTANTIN FILM and BERND EICHINGER present A Bernd Eichinger Production An Uli Edel Film Martina Gedeck Moritz Bleibtreu Johanna Wokalek Nadja Uhl Jan Josef Liefers Stipe Erceg Niels Bruno Schmidt Vinzenz Kiefer Simon Licht Alexandra Maria Lara Hannah Herzsprung Tom Schilling Daniel Lommatzsch Sebastian Blomberg Katharina Wackernagel with Heino Ferch and Bruno Ganz Directed by Uli Edel Written and produced by Bernd Eichinger Based on the book by and in consultation with Stefan Aust 0 Release Date: ……………………………… 1 CONTENTS Synopsis Short 04 Press Notice 04 Press Information on the Original Book 04 Facts and Figures on the Film 05 Synopsis Long 06 Chronicle of the RAF 07 Interviews Bernd Eichinger 11 Uli Edel 13 Stefan Aust 15 Martina Gedeck 17 Moritz Bleibtreu 18 Johanna Wokalek 19 Crew / Biography Bernd Eichinger 20 Uli Edel 20 Stefan Aust 21 Rainer Klausmann 21 Bernd Lepel 21 Cast / Biography Martina Gedeck 22 Moritz Bleibtreu 22 Johanna Wokalek 22 Bruno Ganz 23 Nadja Uhl 23 Jan Josef Liefers 24 Stipe Erceg 24 Niels Bruno Schmidt 24 Vinzenz Kiefer 24 Simon Licht 25 Alexandra Maria Lara 25 Hannah Herzsprung 25 Daniel Lommatzsch 25 Sebastian Blomberg 26 Heino Ferch 26 Katharina Wackernagel 26 Anna Thalbach 26 Volker Bruch 27 Hans-Werner Meyer 27 Tom Schilling 27 Thomas Thieme 27 Jasmin Tabatabai 28 Susanne Bormann 28 2 Crew 29 Cast 29 3 SYNOPSIS SHORT Germany in the 1970s: Murderous bomb attacks, the threat of terrorism and the fear of the enemy inside are rocking the very foundations of the still fragile German democracy. The radicalised children of the Nazi generation led by Andreas Baader (Moritz Bleibtreu), Ulrike Meinhof (Martina Gedeck) and Gudrun Ensslin (Johanna Wokalek) are fighting a violent war against what they perceive as the new face of fascism: American imperialism supported by the German establishment, many of whom have a Nazi past. -

Ideology and Terror in Germany

An Age of Murder: Ideology and Terror in Germany Jeffrey Herf It is best to begin with the obvious. This is a series of lectures about murder, indeed about an age of murder. Murders to be sure inspired by politi- cal ideas, but murders nevertheless. In all, the Rote Armee Fraktion (Red Army Faction, hereafter the RAF) murdered thirty-four people and would have killed more had police and intelligence agencies not arrested them or prevented them from carrying out additional “actions.” Yesterday, the papers reported that thirty-two people were killed in suicide-bomb attacks in Iraq, and thirty-four the day before, and neither of those war crimes were front-page news in the New York Times or the Washington Post. So there is an element of injustice in the amount of time and attention devoted to the thirty-four murders committed by the RAF over a period of twenty- two years and that devoted to the far more numerous victims of radical Islamist terror. Yet the fact that the murders of large numbers of people today has become horribly routine is no reason to dismiss the significance of the murders of a much smaller number for German history. Along with the murders came attempted murders, bank robberies, and explosions at a variety of West German and American institutions. The number of dead could have been much higher. If the RAF had not used pistols, machine guns, bazookas, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), remote-controlled . This article was originally delivered as the opening lecture of the lecture series “The ‘German Autumn’ of 977: Terror, State, and Society in West Germany,” held at the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, on Thursday, September 7, 007. -

SAISON 17-18.Pdf

BALTHASAR-NEUMANN-CHOR BALTHASAR-NEUMANN-ENSEMBLE THOMAS HENGELBROCK 17 INHALT 04 VORWORT 08 ÜBER UNS 20 BALTHASAR-NEUMANN-ENSEMBLES 22 SCHUBERT & BEETHOVEN MIT THOMAS HENGELBROCK 24 MIT IVOR BOLTON IN BASEL 28 „SELVA MORALE“ MIT PABLO HERAS-CASADO 30 MOZART-REQUIEM IN DER ELBPHILHARMONIE 32 „HIMMEL, ERDE, MEER“ MIT OLOF BOMAN 34 WEIHNACHTSTOURNEE MIT MONTEVERDIS MARIENVESPER 36 HAYDN: DIE SCHÖPFUNG 38 GLUCKS „ORPHEUS UND EURYDIKE“ VON PINA BAUSCH 40 J. S. BACH: H-MOLL-MESSE 42 AKADEMIE BALTHASAR NEUMANN SAISON 46 STIPENDIENPROGRAMM 50 CUBAN-EUROPEAN YOUTH ACADEMY 58 SCHULPROJEKTE 17/18 60 THOMAS HENGELBROCK 62 NDR ELBPHILHARMONIE ORCHESTER 70 ORCHESTRE DE PARIS 73 CONCERTGEBOUW ORCHESTRA 74 JOHANNA WOKALEK 78 PARTNER UND PERSÖNLICHES 80 ENGAGEMENT BACKSTAGE 85 EDITION BALTHASAR NEUMANN 86 UNSERE ENSEMBLES IM KINO 88 KALENDER SEHR GEEHRTE LESERINNEN UND LESER, LIEBE FREUNDE DER BALTHASAR-NEUMANN-ENSEMBLES, ein aufregendes und dichtes Jahr liegt hinter den Balthasar-Neumann- Zu Beginn der kommenden Saison wird der Balthasar-Neumann-Chor Ensembles, Thomas Hengelbrock und Johanna Wokalek. Internatio- gemeinsam mit dem NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester in der Elbphil- nalen Tourneen und Projekten der Ensembles folgten hochklassige harmonie zu hören sein. Unter der Leitung von Thomas Hengelbrock Konzerte des Chores mit internationalen Sinfonieorchestern, span- erklingt W. A. Mozarts Requiem in drei Konzerten (siehe Seite 30). Wir nende Kurse und erfolgreiche Auftritte in Havanna – und natürlich: die freuen uns sehr auf unsere Premiere in Hamburgs neuem Wahrzeichen. Eröffnung der Elbphilharmonie! Doch nicht nur im Norden sind unsere Sänger zu hören: Der Balthasar- Neumann-Chor ist im August, September und Oktober als Residenz- Zum Raum wurde hier die Zeit: Das Programm für den Eröffnungs- ensemble nach Basel eingeladen (siehe Seite 24).