Christina Gerhardt. Screening the Red Army Faction: Historical and Cultural Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Bulletin of the GHI Washington

Bulletin of the GHI Washington Issue 43 Fall 2008 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. TERRORISM IN GERMANY: THE BAADER-MEINHOF PHENOMENON Lecture delivered at the GHI, June 5, 2008 Stefan Aust Editor-in-Chief, Der Spiegel, 1994–2008 Recently on Route 73 in Germany, between Stade und Cuxhaven, my phone rang. On the other end of the line was Thilo Thielke, SPIEGEL correspondent in Africa. He was calling on his satellite phone from Dar- fur. For two weeks he had been traveling with rebels in the back of a pick-up truck, between machine guns and Kalashnikovs. He took some- thing to read along for the long evenings: Moby Dick. He asked me: “How was that again with the code names? Who was Captain Ahab?” “Andreas Baader, of course,” I said and quoted Gudrun Ensslin from a letter to Ulrike Meinhof: “Ahab makes a great impression on his first appearance in Moby Dick . And if either by birth or by circumstance something pathological was at work deep in his nature, this did not detract from his dramatic character. For tragic greatness always derives from a morbid break with health, you can be sure of that.” “And the others?” the man from Africa asked, “Who was Starbuck?” At that time, that was not a coffee company—also named after Moby Dick—but the code name of Holger Meins. -

Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict

FRINGE REPORT FRINGE REPORT www.fringereport.com Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict: Springtime for Baader-Meinhof London - MacOwan Theatre - March 05 21-24, 29-31 March 05. 19:30 (22:30) MacOwan Theatre, Logan Place, W8 6QN Box Office 020 8834 0500 LAMDA Baader-Meinhof.com Black Hands / Dead Section is violent political drama about the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It runs for 3 hours in 2 acts with a 15 minute interval. There is a cast of 30 (18M, 12F). The Baader-Meinhof Gang rose during West Germany's years of fashionable middle-class student anarchy (1968-77). Intellectuals supported their politics - the Palestinian cause, anti-US bases in Germany, anti-Vietnam War. Popularity dwindled as they moved to bank robbery, kidnap and extortion. The play covers their rise and fall. It's based on a tight matrix of facts: http://www.fringereport.com/0503blackhandsdeadsection.shtml (1 of 7)11/20/2006 9:31:37 AM FRINGE REPORT Demonstrating student Benno Ohnesorg is shot dead by police (Berlin 2 June, 1967). Andreas Baader and lover Gudrun Ensslin firebomb Frankfurt's Kaufhaus Schneider department store (1968). Ulrike Meinhof springs them from jail (1970). They form the Red Army Faction aka Baader-Meinhof Gang. Key members - Baader, Meinhof, Ensslin, Jan- Carl Raspe, Holger Meins - are jailed (1972). Meins dies by hunger strike (1974). The rest commit suicide: Meinhof (1976), Baader, Ensslin, Raspe (18 October 1977). The play's own history sounds awful. Drama school LAMDA commissioned it as a piece of new writing (two words guaranteed to chill the blood) - for 30 graduating actors. -

Niemals Wie Die Eltern Tergrundkämpferin Der RAF, Zur Gesuchten Terroristin Wurde

Deutschland Spannend, dramaturgisch dicht, durch- aus selbstkritisch und gut geschrieben er- ZEITGESCHICHTE zählt die heute 51-jährige Margrit Schiller von jenem Jahrzehnt ihrer Jugend, in dem sie von der braven Bürgerstochter zur Un- Niemals wie die Eltern tergrundkämpferin der RAF, zur gesuchten Terroristin wurde. Es ist auch ein typisch Margrit Schiller, in den Siebzigern Mitglied der RAF, hat ihre deutsches Drama von der ewigen Suche nach Wahrheit und Identität, vom schwär- Autobiografie geschrieben. Überraschend merischen Idealismus, der in der Katastro- packend erzählt sie ihre tragische Guerrilla-Geschichte. phe von Lüge und Gewalt endet. Ebenso wie der zeitliche Abstand der rst durch die Begegnung mit An- fern ist. War da was, und was war es ei- Jahre mag die geografische Distanz zum dreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin und gentlich? Ort des Geschehens geholfen haben, sich EUlrike Meinhof wurde der jungen Margrit Schiller, von 1971 bis 1979 Mit- der Vergangenheit zu nähern: 1985 ging sie Frau glasklar: „Ich war mein Leben lang glied der RAF, weiß es genau. Dennoch nach Kuba, heiratete einen Kubaner und belogen worden.“ Margrit Schiller, da- brauchte sie, von alten Freunden und Ge- lebt heute mit ihren beiden Kindern in mals 22 Jahre alt, Psychologiestudentin nossen immer wieder gebremst und ver- Montevideo, der Hauptstadt Uruguays. und aktives Mitglied des „Sozialistischen unsichert, viele Jahre, um ihren „Lebens- Zudem: Margrit Schiller war, obwohl sie Patientenkollektivs“ (SPK), hatte die bericht aus der RAF“ unter dem Titel „Es von Anfang an mit dem Gründungskern der Gründertruppe der „Roten Armee Frak- war ein harter Kampf um meine Erinne- RAF zusammentraf, eine Randfigur. Das tion“ (RAF) mehrere Wochen lang in ih- rung“ tatsächlich zu veröffentlichen**. -

Presse Zum Stammheimer Prozess

Top of theweek Terrorist Holger Meins: On hls deathbed after a hunger strike Ford: Summoned from dinner to consult on the Mayaguez Marines were landed to snatch the sailors from their The Baader-Meinhof Gang Pa- 8 captors and an American warship towed their merchant- This week in a specially constructed $5 miliion concrete man to safety. But the Mayaguez affair had far broader fortress billed as "terror-proof," Germany will begin its most ramifications. Its underlying theme was geopolitical, a celebrated court proceeding since Nuremberg-the trial of demonstration of U.S. power and purpose to a world that a band of politicai terrorists known as the Baader-Meinhof had begun to doubt both in the wake of the recent debacles gang. Anthony Collings and Alan Field reported for in Indochina. And despite some sobering morning-after Susan Fraker's story on the urban desperados. In a questions, the over-all success of the operation left the companion piece, Daniel Chu profiles terrorist leader Ford Administration almost giddy with euphoria. With files Ulrike Meinhof and in the back-page interview Edward from Bruce van Voorst, Thornas M. DeFrank, Lloyd H. Behr talks with an earlier revolutionary, Daniel Cohn- Norrnan, Henry W. Hubbard, Paul Brinkley-Rogers, Bendit, leader of the 1968 French student uprising. (Cover Bernard Krisher and others, Peter Goldman, Milton R. photos by Mihaly Moldvay-SternIBlack Star, AP, and dpa. Benjamin and Kirn Willenson describe the Mayaguez Mezzotint by Martin J. Weber.) drama and related events last week in Indochina. Galloping Toward Chaos? Page 12 The World of Computers Paga 36 Economic doomsayers are having a field day in Britain- In the last three decades, the use of computers has and with good reason. -

Ideology and Terror in Germany

An Age of Murder: Ideology and Terror in Germany Jeffrey Herf It is best to begin with the obvious. This is a series of lectures about murder, indeed about an age of murder. Murders to be sure inspired by politi- cal ideas, but murders nevertheless. In all, the Rote Armee Fraktion (Red Army Faction, hereafter the RAF) murdered thirty-four people and would have killed more had police and intelligence agencies not arrested them or prevented them from carrying out additional “actions.” Yesterday, the papers reported that thirty-two people were killed in suicide-bomb attacks in Iraq, and thirty-four the day before, and neither of those war crimes were front-page news in the New York Times or the Washington Post. So there is an element of injustice in the amount of time and attention devoted to the thirty-four murders committed by the RAF over a period of twenty- two years and that devoted to the far more numerous victims of radical Islamist terror. Yet the fact that the murders of large numbers of people today has become horribly routine is no reason to dismiss the significance of the murders of a much smaller number for German history. Along with the murders came attempted murders, bank robberies, and explosions at a variety of West German and American institutions. The number of dead could have been much higher. If the RAF had not used pistols, machine guns, bazookas, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), remote-controlled . This article was originally delivered as the opening lecture of the lecture series “The ‘German Autumn’ of 977: Terror, State, and Society in West Germany,” held at the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, on Thursday, September 7, 007. -

View / Open Chen Oregon 0171N 10747.Pdf

THE LAWS OF TERRORISM: REPRESENTATIONS OF TERRORISM IN GERMAN LITERATURE AND FILM by YANNLEON CHEN A THESIS Presented to the Department of German and Scandinavian and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Yannleon Chen Title: The Laws of Terrorism: Representations of Terrorism in German Literature and Film This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of German and Scandinavian by: Susan Anderson Chairperson Martin Klebes Member Alexander Mathäs Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Yannleon Chen iii THESIS ABSTRACT Yannleon Chen Master of Arts Department of German and Scandinavian June 2013 Title: The Laws of Terrorism: Representations of Terrorism in German Literature and Film Representations of the reasons and actions of terrorists have appeared in German literature tracing back to the age of Sturm und Drang of the 18th century, most notably in Heinrich von Kleist‟s Michael Kohlhaas and Friedrich Schiller‟s Die Räuber, and more recently since the radical actions of the Red Army Faction during the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as in Uli Edel‟s film, The Baader Meinhof Complex. -

The Lasting Legacy of the Red Army Faction

WEST GERMAN TERROR: THE LASTING LEGACY OF THE RED ARMY FACTION Christina L. Stefanik A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor Dr. Christina Guenther Dr. Jeffrey Peake Dr. Stefan Fritsch ii ABSTRACT Dr. Kristie Foell, Advisor In the 1970s, West Germany experienced a wave of terrorism that was like nothing known there previously. Most of the terror emerged from a small group that called itself the Rote Armee Fraktion, Red Army Faction (RAF). Though many guerrilla groupings formed in West Germany in the 1970s, the RAF was the most influential and had the most staying-power. The group, which officially disbanded in 1998, after five years of inactivity, could claim thirty- four deaths and numerous injuries The death toll and the various kidnappings and robberies are only part of the RAF's story. The group always remained numerically small, but their presence was felt throughout the Federal Republic, as wanted posters and continual public discourse contributed to a strong, almost tangible presence. In this text, I explore the founding of the group in the greater West German context. The RAF members believed that they could dismantle the international systems of imperialism and capitalism, in order for a Marxist-Leninist revolution to take place. The group quickly moved from words to violence, and the young West German state was tested. The longevity of the group, in the minds of Germans, will be explored in this work. -

Press Contact: Jonathan Howell Sasha Berman Big World Pictures Shotwell Media Tel: 917-400-1437 Tel: 310-450-5571 [email protected] [email protected]

bigworldpictures.org presents Booking contact: Los Angeles Press Contact: Jonathan Howell Sasha Berman Big World Pictures Shotwell Media Tel: 917-400-1437 Tel: 310-450-5571 [email protected] [email protected] A GERMAN YOUTH (UNE JEUNESSE ALLEMANDE) A film by Jean-Gabriel Périot FranCe/Switzerland/Germany 2015 - 1:1.85 - 5.1 - 92 min SHORT SYNOPSIS A GERMAN YOUTH (Une Jeunesse Allemande) chronicles the political radicalization of some German youth in the late 1960s that gave birth to the Red Army FaCtion (RAF), a German revolutionary terrorist group founded notably by Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, as well as the images generated by this story. The film is entirely produCed by editing preexisting visual and sound arChives and aims to question viewers on the signifiCanCe of this revolutionary movement during its time, as well as its resonanCe for today’s soCiety. LONG SYNOPSIS In the 1960s, the young demoCraCy of West Germany was embarrassed by its Nazi past, and ingrown in its role as imperialist and Capitalist outpost faCed by its Communist double. The postwar generation, in direCt ConfliCt with their fathers, was trying to find its plaCe. The student movement exploded in 1966. The pas de deux between students and the government deteriorated, and radiCalized those involved in a gradual esCalation of violenCe and reprisals. From this seething youth emerged the journalist Ulrike Meinhof, filmmaker Holger Meins, students Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin, as well as the lawyer Horst Mahler. When the student movement Collapsed at the end of ’68, they remained isolated in their radiCalism, and desperately sought ways to Continue the revolutionary struggle. -

An Examination of Gerhard Richter's 18. Oktober 1977 in Relation to the West

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Gewalt und Gedächtnis: An Examination of Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977 in Relation to the West German Mass Media Matthew McDevitt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, European History Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation McDevitt, Matthew, "Gewalt und Gedächtnis: An Examination of Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977 in Relation to the West German Mass Media". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2019. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/760 Gewalt und Gedächtnis: An Examination of Gerhard Richter’s 18. Oktober 1977 in Relation to the West German Mass Media A Senior Thesis Presented By Matthew P. McDevitt To the Art History Department in Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in Art History Advisor: Professor Michael FitzGerald Trinity College Hartford, Connecticut Spring 2019 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………...………………………………………………………3 Chapter I: History and Ideology of the Red Army Faction………………………...4 Chapter II: Gerhard Richter: Beginnings, Over and Over Again……………........40 Chapter III: 18. Oktober 1977 and the West German Mass Media……………….72 Appendix of Images……………………………………………………………… 96 Bibliography………………………………………………………………….… 132 3 Thank You Thank you, Mom and Dad, for supporting me unrelentingly and trusting me unsparingly, even in times when I’m wrong. Thank you for those teaching moments. Thank you to Ryan and Liam for never changing, no matter how scattered we are. -

0020071017 0.Pdf

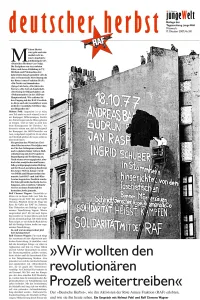

2 deutscher herbst Mittwoch, 17. Oktober 2007, Nr. 241 junge Welt Unser Titelfoto zeigt ein Wandbild in der Ham- »An die Massenagitation haben burger Hafenstraße. Es entstand 1986 in »Solida- wir nicht geglaubt. Wir haben rität mit der RAF« zum neunten Jahrestag des dieses Revolutionskonzept der »Deutschen Herbstes«. Der Senat der Freien und diversen K-Gruppen nicht für Hansestadt ließ es unter massivem Polizeischutz Helmut Pohl übermalen. voll genommen.« Neben Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin und Jan immer wieder auf, um das gleich heraus- war absolut kein Terrain für eine Stadt- Raspe (siehe Fußnote 5) zugreifen, wie die angebliche Geschichte guerilla, wie wir sie wollten. Sie kamen wird auch Ingrid Schubert von Ulrike 3 verbraten wird. Schon von also nach Westdeutschland, und ich ge- (geb. 1944) erwähnt. Die Anfang an, seit 1970/71, wird behauptet, hörte dann zu den ersten, die von Ulrike Mitbegründerin der RAF Ulrike hätte aussteigen wollen aus dem angesprochen wurden. Sie fragte mich, war an der Befreiung von bewaffneten Kampf. Das ist völliger Un- wie ich zum bewaffneten Kampf stehe. Andreas Baader beteiligt sinn. Es ist psychologische Kriegsfüh- Na ja, ich bin gleich mitgegangen und ha- und wurde im Oktober rung und Propaganda und man muß das be mit ihr in der ersten Zeit zu Beginn der 1970 verhaftet. Sie war in Zusammenhang mit den späteren An- Siebziger eng zusammengearbeitet. seit 1976 im siebenten griffen bringen: Isolationsfolter im toten Ulrike Meinhof wurde in bürger- Stock in Stammheim, bis Trakt, der Versuch einer Zwangsunter- lich-aufgeklärten Verhältnissen zur Zwangsverlegung am suchung ihres Gehirns. 4 Es war in allem groß – und es mag auf sie und viel- 18.8.1977 nach München- der Versuch, die Revolutionärin Ulrike zu leicht auch auf die Pfarrerstochter Stadelheim. -

Terry Delaney Photographs from an Undeclared War Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the Run 67-77 by Astrid Proll

page 24 • variant • volume 2 number 7 • Spring 1999 Margit Schiller being brought before the Hamburg press, October 1971 Terry Delaney Photographs from an undeclared war Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the run 67-77 by Astrid Proll From the mid 1970s until the early ‘80s I visited question hanging over the ranks of faces: ‘Have you vanquished enemies on stakes in public places; a kind Germany regularly. Those were different times, it has seen these people?’ There was something chilling of salutary lesson to the potentially disaffected, to be said, and the Europe of ‘no borders’ was still about wanted posters displayed so prominently in a perhaps, or a triumphalist gesture akin to the display some way off. On the train from Brussels to Cologne modern European state although a cursory glance of sporting trophies before one’s loyal support? burly German Border Police stalked the corridors, would not have revealed quite how chilling these The cover of Astrid Proll’s Baader Meinhof, pistols prominent on their robust hips, their posters were. A closer look revealed something odd, Pictures on the Run 67-77 appears to have been taken intimidating manner impressive and accomplished. indeed disturbing, about some of the photographs. from one such poster. There are the rows of young They carried with them what looked for all the world Their subjects were dead. I’m not sure how these faces, serious, but in this case healthy, the pictures like outsized photograph albums. These they would images had been made, whether the corpses had been now somehow reminiscent of one of those American flick through occasionally as they travelled through photographed on mortuary slabs or had somehow High School Yearbooks.