Aboriginal Peoples in Their Movement to Assert Their Ancestral Rights and Their Distinct Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chapter in Penobscot History

The Rebirth of a Nation? A Chapter in Penobscot History NICHOLAS N. SMITH Brunswick, Maine THE EARLIEST PERIOD The first treaty of peace between the Maine Indians and the English came to a successful close in 1676 (Williamson 1832.1:519), and it was quickly followed by a second with other Indians further upriver. On 28 April 1678, the Androscoggin, Kennebec, Saco and Penobscot went to Casco Bay and signed a peace treaty with commissioners from Massachusetts. By 1752 no fewer than 13 treaties were signed between Maine Indians negotiating with commissioners representing the Colony of Massachu setts, who in turn represented the English Crown. In 1754, George II of England, defining Indian tribes as "independent nations under the protec tion of the Crown," declared that henceforth only the Crown itself would make treaties with Indians. In 1701 Maine Indians signed the Great Peace of Montreal (Havard [1992]: 138); in short, the French, too, recognized the Maine tribes as sov ereign entities with treaty-making powers. In 1776 the colonies declared their independence, terminating the Crown's regulation of treaties with Maine Indians; beween 1754 and 1776 no treaties had been made between the Penobscot and England. On 19 July 1776 the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Micmac Indi ans acknowledged the independence of the American colonies, when a delegation from the tribes went to George Washington's headquarters to declare their allegiance to him and offered to fight for his cause. John Allan, given a Colonel's rank, was the agent for the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Micmac, but refused to work with the Penobscot, .. -

Tales of Montréal POINTE-À-CALLIÈRE, WHERE MONTRÉAL WAS BORN

: : Luc Bouvrette : Luc Pointe-à-Callière, Illustration Pointe-à-Callière, Méoule Bernard Pointe-à-Callière, Collection / Photo 101.1742 © © TEACHER INFORMATION SECONDARY Tales of Montréal POINTE-À-CALLIÈRE, WHERE MONTRÉAL WAS BORN You will soon be visiting Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Complex with your students. The Tales of Montréal tour takes place in an exceptional archaeological and historical setting. Your students will discover the history of Montréal and its birthplace, Fort Ville-Marie, as they encounter ruins and artifacts left behind by various peoples who have occupied the site over the years. BEFORE YOUR VISIT Welcome to Pointe-à-Callière! “Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology OBJECTIVES and History Complex, is the city’s birthplace ¬ Learn the history of the pointe at Callière. and classified as a heritage site of national ¬ Understand that Fort Ville-Marie, the ruins importance.” of which the students will see, is the birthplace This statement serves as a stepping off point of Montréal. for students to learn about the history of the site ¬ Learn more about the archaeological digs of Pointe-à-Callière, Fort Ville-Marie, and Montréal’s at the site. first Catholic cemetery, the remains of which they will see when they tour the museum. COMPETENCIES DEVELOPED The students will also learn more about Pointe-à-Callière’s heritage conservation mission, ¬ Examine the facts, figures, actions, causes, as shown through the archaeological digs, the and consequences of social phenomena. exhibition of ruins and artifacts unearthed during ¬ Understand the concepts of continuity the digs, and the acquisition of historical buildings and change in relation to the present. -

TREATIES RECOGNITION WEEK FIRST FULL WEEK of NOVEMBER Trentu.Ca/Education/Resources

TREATIES RECOGNITION WEEK FIRST FULL WEEK OF NOVEMBER trentu.ca/education/resources ABOUT A treaty is an agreement between Nations. Initially, treaties between the British or the French and the Indigenous pop- ulations were a peaceable agreement that represented some kind of mutual sharing, trading or aid. Later, when the first land surrender treaties were signed, the Indigenous people really did not understand that land was being “given” away due to language barriers and misrepresentations and because the concept of land “ownership” was foreign to them. By the time of Canadian Confederation in 1867 only a fraction of Ontario had not been ceded by a treaty. Today in Canada there are approximately 70 treaties between 371 First Nations and the Crown. The treaties represent the rights of more than 500,000 Indigenous people. Since the creation of Canada’s Claims Policy in 1973 there have been 16 comprehensive land claims settled. These claims include the Yukon First Nations, the Nisga’a Agreement, the Tlicho Agreement and the largest land claim settlement in Canadian history, the creation of Nunavut in 1999. Friendship, Peace and Neutrality Treaties The Great Peace of Montreal. Signed by over 40 Nations, the Great Peace Treaty 1701 of 1701 ended wars between the French, the Haudenosaunee and the Great Lakes Nations who had been fighting over the fur trade. 1725 The British sign treaties of Peace and Friendship to with the Mi’kmaq and the Maliseet in Nova Scotia. 1779 Treaty of Swegatchy. The Indigenous Nations allied with the French sign a neutrality treaty after the French lose Montreal and Quebec. -

Chapter 4 Notes

CHAPTER 4 COMPETITION FOR TRADE CULTURE IN CONTACT We find it hard to understand people who are different from us. Sometimes we think our way is the best way. ETHNOCENTRIC – When you meet someone from another country you think your way is best. CHANGING FIRST IMPRESSIONS First nations people and Europeans had to learn to get along because they wanted to trade with each other. They had to respect one another’s differences. THE FUR TRADE: THE FOUNDATION OF AN ECONOMY PARTNERS IN TRADE European traders and First nations hunters and trappers had a partnership in the fur trade. Each had something the other wanted. Steven Krahn Tuesday, November 5, 2013 9:31:25 AM MT First Nations people wanted metal goods that came from Europe. (pots, knives, axes, copper wire and guns) These goods were stronger and lasted longer. First Nations traded goods such as blankets, cloth and thread. Europeans wanted furs – marten, otter, bear, lynx, muskrat, wolf and beaver. Europeans used furs for trim on coats and jackets. Most popular was the beaver felt hats. BARTER SYSTEM Europeans used metal coins for money, but also traded goods. The exchange of goods was called barter. Did they benefit equally from trade? European fur traders were paid about 10 times for pelts than they paid for goods to trade. THE THREE KEY PLAYERS First Nations In winter they hunted and trapped animals. Women skinned the animals and prepared the pelts. In the spring they travelled to the posts to trade the furs for goods. Merchants French and British merchants financed and organized the fur trade. -

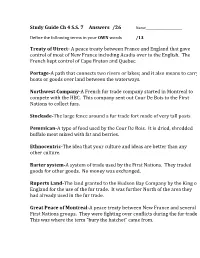

Study Guide Ch 4Answers

Study Guide Ch 4 S.S. 7 Answers /26 Name_________________________ Define the following terms in your OWN words /13 Treaty of Utrect- A peace treaty between France and England that gave control of most of New France including Acadia over to the English. The French kept control of Cape Breton and Quebec. Portage-A path that connects two rivers or lakes; and it also means to carry boats or goods over land between the waterways. Northwest Company-A French fur trade company started in Montreal to compete with the HBC. This company sent out Cour De Bois to the First Nations to collect furs. Stockade-The large fence around a fur trade fort made of very tall posts Pemmican-A type of food used by the Cour De Bois. It is dried, shredded buffalo meat mixed with fat and berries. Ethnocentric-The idea that your culture and ideas are better than any other culture. Barter system-A system of trade used by the First Nations. They traded goods for other goods. No money was exchanged. Ruperts Land-The land granted to the Hudson Bay Company by the King of England for the use of the fur trade. It was further North of the area they had already used in the fur trade. Great Peace of Montreal-A peace treaty between New France and several First Nations groups. They were fighting over conflicts during the fur trade. This was where the term “bury the hatchet” came from. Chipewyan-A First Nation group in the North. A NWC fur trade fort was set up close to them. -

The Governor, the Merchant, the Soldier, the Nun, and Their Slaves

The Governor, the Merchant, the Soldier, the Nun, and their Slaves Household Formation and Kinship in Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Montréal By Alanna Loucks A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada Final (QSpace) submission April, 2019 Copyright ã Alanna Loucks, 2019 Abstract From 1650 onward, the city of Montréal became a crossroads that connected colonial French, Indigenous, and African worlds. A study of the geo-cultural landscapes of Montréal presents an opportunity to analyze the commercial, social, and familial networks of diverse peoples in a space defined by mobility, fluidity, and growing stability. The purpose of this research project is to illustrate how French households in Montréal between 1650 and 1750, which included Indigenous and African descent slaves and other labourers who are generally not considered as a part of family formation, contributes to our understanding of the interconnected nature of the French colonial world. There are different ways to explore the commercial, social, and familial connections that shaped Montréal into a crossroads. This project explores spatial, demographic, and household composition as three interrelated dimensions of Montréal’s networks. I utilize the idea of concentric circles of connection, moving from a macro- to a micro-historical level of analysis. I begin by considering Montréal’s geographic position in North America; next I examine the physical layout of the built environment in Montréal and follow with an analysis of Montréal’s demographic development. The thesis concludes with the reconstruction of the commercial, social, and familial networks that developed in Montréal society and within individual households. -

The Great Peace of Montréal: a Story of Peace Between Nations

The Great Peace of Montréal: a story of peace between nations AN IMPORTANT MILESTONE IN THE HISTORY OF QUÉBEC Québec has a long-standing tradition of respect for the Indigenous peoples that can be traced back to 1701, when Montréal was the setting for an event that changed the course of history. A TURNING-POINT IN FRENCH-NATIVE RELATIONS The signing of the Great Peace ended several decades of conflict between the Iroquois, who were allied with the British, and the French along with their First Nations allies. It also marked a turning-point in French-Native relations and set the scene for an era of peace that lasted until the conquest of New France in 1760. In July 1701, four of the five Iroquois nations, along with the First Nations that were allied with the French and lived mostly in the Great Lakes region, travelled to Montréal to discuss a peace treaty. Picture : Centre des archives d’outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence (Archives nationales, France), C 11 A 19 fol. 41-44. The document was signed on August 4, 1701 by over thirty different nations. They agreed to stop waging war on each other, to consider themselves allied, and to recognize the Governor of New France as The Great Peace of Montréal, a peace treaty signed in 1701 a mediator if a new conflict arose. The Iroquois League agreed to by the Governor of New France, Louis-Hector de Callière, remain neutral in the event of a war between the British and 39 First Nations communities. and the French. -

The Ohio Country and Indigenous Geopolitics in Early Modern North America, Circa 1500–1760

The Ohio Country and Indigenous Geopolitics in Early Modern North America, circa 1500–1760 Elizabeth Mancke Ohio Valley History, Volume 18, Number 1, Spring 2018, pp. 7-26 (Article) Published by The Filson Historical Society and Cincinnati Museum Center For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/689416 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 02:11 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] The Ohio Country and Indigenous Geopolitics in Early Modern North America, circa 1500–1760 Elizabeth Mancke rom the late fifteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, the North American lands between Lake Erie and the Ohio River were a volatile nexus of alliance systems, confederacies, empires, and states. The major Ftransportation corridors that ran through and encircled them contributed to their transition from a settled zone, to a conflict zone, to a largely depopulated buffer zone and hunting grounds and then to a resettlement zone for diverse Indigenous peoples. As these lands were being resettled in the eighteenth cen- tury, they became known as the Ohio Country, a region characterized in part by its physical geography and in part by its human geography, by the diversity of Native peoples who resettled there and began forging a pan-Indigenous, multiethnic polity.1 This essay contends that in the early eighteenth century the Ohio Country was defined by the Indigenous peoples who occupied and competed to control it. Their definition was more consequential than is recognized by most schol- ars, who tend, often unwittingly, to privilege a definition based on French and British competition in the upper Ohio Valley and the role Indigenous peo- ples played in that European struggle. -

Rivalry and Alliance Among the Native Communities of Detroit, 1701--1766 Andrew Keith Sturtevant College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 Jealous neighbors: Rivalry and alliance among the native communities of Detroit, 1701--1766 andrew Keith Sturtevant College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sturtevant, andrew Keith, "Jealous neighbors: Rivalry and alliance among the native communities of Detroit, 1701--1766" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623586. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-crtm-ya36 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEALOUS NEIGHBORS: RIVALRY AND ALLIANCE AMONG THE NATIVE COMMUNITIES OF DETROIT, 1701-1766 Andrew Keith Sturtevant Frankfort, Kentucky Master of Arts, The College of William & Mary, 2006 Bachelor of Arts, Georgetown College, 2002 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2011 Copyright 2011, Andrew Sturtevant APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment -

"A Little Flesh We Offer You": the Origins of Indian Slavery in New France Author(S): Brett Rushforth Source: the William and Mary Quarterly, Vol

"A Little Flesh We Offer You": The Origins of Indian Slavery in New France Author(s): Brett Rushforth Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 60, No. 4 (Oct., 2003), pp. 777-808 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3491699 Accessed: 28-12-2018 20:47 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3491699?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly This content downloaded from 141.217.20.120 on Fri, 28 Dec 2018 20:47:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "A Little Flesh We Offer You": The Origins of Indian Slavery in New France Brett Rushforth It is well known the advantage this colony would gain if its inhabitants could securely purchase and import the Indians called Panis, whose country is far dis- tant from this one. -

Making a Just and Fair Canada

154_ALB6SS_Ch7_F2 2/13/08 4:48 PM Page 154 CHAPTER Making a Just and 7 Fair Canada Imagine that you are a member of a girls’ soccer team who is playing in the annual tournament. At the beginning of your third game, the referee points to a Muslim girl on your team and tells her that she can’t play because she is wearing a hijab, or headscarf. The referee is also Muslim. On these two pages you will read about a girls’ Grade 6 soccer team in this exact situation. The Québec Soccer Federation rule that the referee was following states: “The wearing of the Islamic veil or any other religious item is not permitted.” Enforcing the Rules When Asmahan Mansour was forced to leave her soccer game because she wouldn’t remove her hijab, she was very upset. So were her coach, teammates, and many adults watching the tournament. Asmahan’s team walked out of the soccer tournament. “It’s her religion and she can’t just take it off,” explained Sarah Osborne, one of Asmahan’s teamates. “This is not fair. We’re only 11. We just wanted to play soccer.” Four other teams from across Canada also left the tournament. ■ Why do you think Asmahan’s teammates and some other teams left the tournament? ■ What would you have done in their place? 154_ALB6SS_Ch7_F2 2/13/08 4:48 PM Page 155 The Right to Practise Religion Many newspaper writers, television commentators, politicians, sports organizations, and members of the public became involved in debates about whether what happened to Asmahan was just and fair. -

Nicolas Perrot from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Nicolas Perrot From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Nicolas Perrot sketch Nicolas Perrot (1644–1717), explorer, diplomat, and fur trader, was one of the first white men in the Upper Mississippi Valley. Statute of Nicolas Perrot (far right) in front of historic Brown County Courthouse, Green Bay, Wisconsin. 1 Map showing Nicolas Perrot’s travels and where he helped establish forts. Nicolas Perrot and his men founded the Fort called Saint Antoine in the spring of 1686 on the eastern shore of Lake Pepin. The purpose of this expedition was to establish alliances with the Ioway and Dakota Indians in order to expand French interests in the fur trade market. Although Perrot's venture was not the first French excursion into the upper Mississippi Valley, his was the first attempt to establish a foothold in this region Biography Born in France, he came to New France around 1660 with Jesuits and had the opportunity to visit Indian tribes and learn their languages. He formed a fur trading company around 1667 and undertook expeditions to various tribes and land in and around present-day Wisconsin. He was sometimes the first white man seen by the native peoples and was generally well received. In 1670 he was an interpreter for Daumont de Saint-Lusson, a French commissary assigned to the country of the Ottawas, Amikwas, Illinois, and other Indian natives to be discovered in the direction of Lake Superior. He continued to travel around these areas and engaged in fur trading, giving the natives such items as cooking kettles and hatchets (to replace stone tools).