Suburban Pastoral: Strawberry Fields Forever and Sixties Memory Daniels, Stephen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

FLAME TREE MUSIC PORTAL Extends the Reach of the Flame Tree Music Books

FLAME TREE PUBLISHING NEW TITLES & BACKLIST 2020 FLAME TREE MUSIC • Page 36 FLAME TREE PUBLISHING NEW TITLES & BACKLIST 2020 FLAME TREE MUSIC • Page 37 Pack of 3 books, shrink-wrapped, with a bellyband • Each 64pp book is paperback, with a stitched spine FLAME TREE • Chord and How to Play books are full colour inside MUSIC • Journals contain blank, ruled pages with chord boxes and manuscript paper Easy to Use • Internet links to flametreemusic.com Great for travel, quick access Easy to use, slim and adaptable, the Pick Up & Play offer free audio access to hear the at home, planning for and playing 3-Pack Kits will fit in a bag, or within easy Piano Sheet Music chords and scales. with others reach, as a constant companion. Rock Icons Jake Jackson Jake Jackson Definitive Encyclopedias 3-BOOK WORKING KIT FOR GUITAR 3-BOOK WORKING KIT FOR PIANO & KEYBOARD An essential aid to learning and making notes when playing the guitar, An essential aid to learning and making notes when playing the keyboard, writing songs and working with others. The Guitar Chords book gives 4 writing songs and working with others. The Piano & Keyboard Chords chords per key, plus an extra chord section for variations. book gives left- and right-hand chords, plus an extra section for variations. The Play Guitar book covers all essentials to help you start up quickly, The Play Piano & Keyboard book covers all essentials to help you start or refresh your memory, with scales for solos and basic techniques up quickly, or refresh your memory, with scales and modes explained. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

Background Dates for Popular Music Studies

1 Background dates for Popular Music Studies Collected and prepared by Philip Tagg, Dave Harker and Matt Kelly -4000 to -1 c.4000 End of palaeolithic period in Mediterranean manism) and caste system. China: rational philoso- c.4000 Sumerians settle on site of Babylon phy of Chou dynasty gains over mysticism of earlier 3500-2800: King Menes the Fighter unites Upper and Shang (Yin) dynasty. Chinese textbook of maths Lower Egypt; 1st and 2nd dynasties and physics 3500-3000: Neolithic period in western Europe — Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (ends 1700 BC) — Iron and steel production in Indo-Caucasian culture — Harps, flutes, lyres, double clarinets played in Egypt — Greeks settle in Spain, Southern Italy, Sicily. First 3000-2500: Old Kingdom of Egypt (3rd to 6th dynasty), Greek iron utensils including Cheops (4th dynasty: 2700-2675 BC), — Pentatonic and heptatonic scales in Babylonian mu- whose pyramid conforms in layout and dimension to sic. Earliest recorded music - hymn on a tablet in astronomical measurements. Sphinx built. Egyp- Sumeria (cuneiform). Greece: devel of choral and tians invade Palestine. Bronze Age in Bohemia. Sys- dramtic music. Rome founded (Ab urbe condita - tematic astronomical observations in Egypt, 753 BC) Babylonia, India and China — Kung Tu-tzu (Confucius, b. -551) dies 3000-2000 ‘Sage Kings’ in China, then the Yao, Shun and — Sappho of Lesbos. Lao-tse (Chinese philosopher). Hsai (-2000 to -1760) dynasties Israel in Babylon. Massilia (Marseille) founded 3000-2500: Chinese court musician Ling-Lun cuts first c 600 Shih Ching (Book of Songs) compiles material from bamboo pipe. Pentatonic scale formalised (2500- Hsia and Shang dynasties (2205-1122 BC) 2000). -

MM" ,/ Ljtta) Fln; #-{

I99 KINGSToN RoAD LoNDON SW}g TeI,OI_540 oasi.. l 'rv MM" ,/ lJttA) fln; #-{ tru'rtterry Xffm-ry*LSS.e.Re.ffiS. seeffixss eg-ge"k&R"-4ffi *es-e cherry Red Recolds r. the Lond,on baeed, independ.ont Record. conpanyr have slgned, a three yo&r llce,'se a,greenent wtth the Sristol based gecords. Eeartbeat cherr! n"a sill-be marke! ?"d. prornote arl Eeartbeat product whicb wtli i*clud.ed, ritb cherry Redrs d,istriiutlon d.ear rriu-fp"rtan Rec ordg r First new release und,er the agreement nill be a l2,r track single by 3ristol. band. t0LAX0 4 $ersht6$ho"'A}n3.1'"]';f;i".;i'i:}'ix$i*;';;'kgr+BABrEsr wh,Lch iE rereased of stoqk for ine rait i;;; rsonthE. said raln Mc$ay on behar.f ol cherry Red,r?here are talented acts energlng f:rom tnl gristor so&e vexy will retaia totarTeY coirtioi-over &r€*r seaibeat conplo tetv ret'ain tbeir i"u*i-ii-"iiti.tbatr A. arrd, R. gid,e and havo the ad.vantage fiowever, they irr.rl 'ow of nationar *riirruutron asd havE il:fffr,tronotionaL and' markotlns raciriii.u ;;-*;;; i*,*r" ].lore luformatioa lain Uc$ay on 540 6g5I. ilrrsct*r: IeenMclrlry Registered Office, fr* S*uth .&udi*y Stre*t, fu*nc3*n W I t{u*r,r*+xl b€gK\S* €.ft*Jz-lr{ & Glaxo Babies : rliine Ilionths to the liscot (Cherry Red./ Heartbeat) Of all the new bands spawned in the Sristol area over the last few years, very few have had any lasting effect on the national scener most having dissolved into a mediochre pop/p.p soup. -

Mick 56 Template

THE MICK 56 is... THE LOST ZIGZAG Finally the March 1986 issue of ZigZag, which never made it to the shops, can be seen. More or less. GO-BETWEENS * RUBY TURNER * RED WEDGE * DEF JAM * DEREK JAMESON * JOHN LYDON * PET SHOP BOYS * BO DIDDLEY * BALAAM & THE ANGEL * DEREK JARMAN * SWANS * FINE YOUNG CANNIBALS * THE GODFATHERS EDITORIAL VOMIT... ZIGZAG magazine was the best music publication Britain ever the whole Indie Dance shenanigans where he was touring the had. It started humble and then developed some bite, always world as a DJ. remaining committed to the cause of covering music the writers believed mattered, as opposed to what felt trendy. Many music journalists I have met have tried being cool or wanted to be important, which is pretty much missing the During the 1970’s you had four music papers (Melody Maker, point. You’re either cool or you’re not and trying to be cool NME, Sounds and Record Mirror), some pop mags which I emphatically means the latter. On radio we had Peel, and from can’t recall, and ZigZag. Almost a fanzine upgrade, ZigZag was the writing corner we have Kris. That’s the standard he’s set. a curious amalgam of folk, West Coast rock and Pubrock. You He’s still doing it, still enthusiastic, still hilarious, still on the found interviews in ZigZag that the music papers either ball. He even rescues rabbits. couldn’t be bothered to do, or didn’t realise were necessary, and when Punk came along and Kris Needs infused it with a It’s for that reason that I was dismayed when being rebellious spirit it was the only publication in Britain handling interviewed for Trakmarx magazine, to learn Kris thought I’d the new sounds naturally. -

Get 'Em out by Friday the Official Release Dates 1968-78 Introduction

Genesis: Get ‘Em Out By Friday The Official Release Dates 1968-78 Introduction Depending on where one looks for the information, the original release dates of Genesis singles and albums are often misreported. This article uses several sources, including music paper cuttings, websites and books, to try and determine the most likely release date in the UK for their officially released product issued between 1968 and 1978. For a detailed analysis to be completed beyond 1978 will require the input of others that know that era far better than I with the resources to examine it in appropriate levels of detail. My own collection of source material essentially runs dry after 1978. As most people searching for release dates are likely to go to Wikipedia that is where this search for the truth behind Genesis’ back catalogie. The dates claimed on Wikipedia would themselves have come from a number of sources referenced by contributors over the years but what these references lack is the evidence to back up their claims. This article aims to either confirm or disprove these dates with the added bonus of citing where this information stems from. It’s not without a fair share of assumptions and educated deductions but it offers more on this subject than any previously published piece. The main sources consulted in the writing of this article are as follows: 1. The Genesis File Melody Maker 16 December 1972 2. Genesis Information Newsletter Issue No. 1 October 1976 3. Wax Fax by Barry Lazzell - a series of articles on Genesis releases published in Sounds over several weeks in 1977 4. -

The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Reiter, Roland: The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons. Bielefeld: transcript 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839408858 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. -

A History of International Beatleweek (PDF)

The History of International Beatleweek International Beatleweek celebrates the most famous band in the world in the city where it was born – attracting thousands of Fab Four fans and dozens of bands to Liverpool each year. The history of Beatleweek goes back to 1977 when Liverpool’s first Beatles Convention was held at Mr Pickwick’s club in Fraser Street, off London Road. The two-day event, staged in October, was organised by legendary Cavern Club DJ Bob Wooler and Allan Williams, entrepreneur and The Beatles’ early manager, and it included live music, guest speakers and special screenings. In 1981, Liz and Jim Hughes – the pioneering couple behind Liverpool’s pioneering Beatles attraction, Cavern Mecca – took up the baton and arranged the First Annual Mersey Beatle Extravaganza at the Adelphi Hotel. It was a one-day event on Saturday, August 29 and the special guests were Beatles authors Philip Norman, Brian Southall and Tony Tyler. In 1984 the Mersey Beatle event moved to St George’s Hall where guests included former Cavern Club owner Ray McFall, Beatles’ press officer Tony Barrow, John Lennon’s uncle Charles Lennon and ‘Father’ Tom McKenzie. Cavern Mecca closed in 1984, and after the city council stepped in for a year to keep the event running, in 1986 Cavern City Tours was asked to take over the Mersey Beatle Convention. It has organised the annual event ever since. International bands started to make an appearance in the late 1980s, with two of the earliest groups to make the journey to Liverpool being Girl from the USA and the USSR’s Beatle Club. -

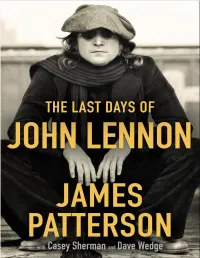

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24