Lord Haw-Haw -- and William Joyce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Documents, Autographs & Ephemera

Historical Documents, Autographs & Ephemera Thursday 18 August 2011 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Old Shippon Wall Under Heywood Church Stretton SY6 7DS Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Historical Documents, Autographs & Ephemera) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Correspondents include Archbishops, Bishops and members of West Midlands -Manor of Sedgley the minute books of the the aristocracy. Nelson was an active churchman and wrote Manor commencing February 27th 1817, and May 12th 1821, many hymns and was foremost in compiling the 'Sarum vellum covers, soiled but completely legible, interior contents Hymnal'. A number of these letters are from the Bishop of on paper written in a neat legible hand and in good order.4to. Salisbury who collaborated with Nelson on this work Estimate: £200.00 - £400.00 Estimate: £150.00 - £200.00 Lot: 2 Lot: 7 Autograph -Lord Randolph Churchill original membership Ireland -Acts of Parliament group of approx seven printed Acts application form for the Amphitryon Club, London, signed in of Parliament relating to the Census of Ireland together with pencil by Lord Randolph Churchill as sponsor for Prince extensive printouts on the 1821, 1831 & 1841 censuses Dolgoroukoff, the Imperial Attache for the Russian Ambassador compared (who has also signed), with two further signatures. Dated March Estimate: £70.00 - £100.00 31st 1894. Together with a similar application form for Prince Boris Priatopolk-Czetwertynski, dated August 24th 1891, signed by Lord de Grey and Count Andes Kreutz.Rare. The Lot: 8 Amphitryon Club was, in its day, the most sought after Ireland -Sean O'Duffy scarce printed handbill being a reprint of Gentleman's Club in London, boasting by far the highest prices a letter by Sean O'Duffy which was written to the Irish for food and drink. -

Muslim Intellectuals and the Perennial Philosophy in the Twentieth Century1

Sophia Perennis Vol. 1, Number 1, 2009 Iranian Institute of Philosophy Tehran/Iran Muslim Intellectuals and the Perennial Philosophy in the Twentieth Century1 Zachary Markwith Abstract: This paper will examine how Muslim intellectuals, as a result of their attachment to the doctrine of Divine Unity (tawh¤īd), the Quran, Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad, and the doctrines and methods of Sufism, were largely responsible for the restating of the perennial philosophy in the West in the twentieth century. The article consists of four sections: an introduction to the term 'philosophia perennis'; the place of the perennial philosophy in the Qur'an and Sunnah; the perennial philosophy and the Islamic intellectual Tradition; the lives, writings, and intellectual contributions of the five most important Muslim perennialists of the twentieth century, namely, Guénon, Schuon, Burckhardt, Lings, and Nasr The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the inextricable link between Islam and the perennial philosophy in the twentieth century, while defending the role that orthodoxy and orthopraxy play in any authentic expression of the perennial philosophy. Key terms: Perennial Philosophy, Rene Guenon, Frithjof Schuon, Titus Burkhardt, Martin Lings, Seyyed Hossein Nasr Number 1, Winter 2009 39 Muslim Intellectuals and the Perennial Philosophy There is an attempt from certain quarters to marginalize the relationship between Islam and the perennial philosophy, and specifically what Frithjof Schuon called, “the transcendent unity of religions.” On the one hand, some interpreters of Schuon and the perennial philosophy have denied, in the name of pure esoterism, the necessary religious forms and discipline which allow man to transcend himself, and have an authentic vision of Reality. -

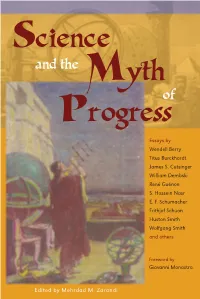

Science and the Myth of Progress Appears As One of Our Selections in the Perennial Philosophy Series

Religion/Philosophy of Science Zarandi Can the knowledge provided by modern science satisfy our need to know the most profound nature of reality and of humanity? Science “The great advantage of this book is that it puts together texts of authors (scientists, philosophers and theologians) whose lucidity about modern and the science goes far beyond emotional reaction and moralist subjectivity; and this ‘tour de force’ is accomplished from within the point of view of the Science yth main traditional religions. Here, Science and Faith are reconciled in an M unexpected way: scientific objectivity is not an issue; but the real issue, where one sees no proof of progress, is whether man is capable of using of modern science properly. A must for the reader who wants to sharpen his or her discernment about modern science.” —Jean-Pierre Lafouge, Marquette University rogress and the and P “Writing as an active research scientist, living in the present Culture of Disbelief created (partly unwittingly) by the science establishment, I can Essays by think of no Research and Development project more significant to the Wendell Berry future of humanity than putting ‘science’ back into its proper place as a Titus Burckhardt part of culture, but not its religion. This book is an excellent contribution Myth to that paramount goal.” James S. Cutsinger —Rustum Roy, Evan Pugh Professor of the Solid State, Emeritus, William Dembski Pennsylvania State University René Guénon “A wonderful collection of essays dealing with the supposed conflict S. Hossein Nasr between religion and science from both a scientific and a metaphysical of E. -

IBA Centre for Excellence in Islamic Finance Library Resources

IBA Centre for Excellence in Islamic Finance Library Resources Titles Book Name Author Publisher Sahih Muslim Imam Muslim Darul Ishaat Sahih Muslim Imam Muslim Darul Ishaat 1 Sahih Muslim Imam Muslim Darul Ishaat Sahih Muslim Imam Muslim Darul Ishaat Voices Of Islam Vincet J. Cornell Suhail Academy Voices Of Islam Vincet J. Cornell Suhail Academy 2 Voices Of Islam Vincet J. Cornell Suhail Academy Voices Of Islam Vincet J. Cornell Suhail Academy Voices Of Islam Vincet J. Cornell Suhail Academy Islamic Economics: Annonated Sources In English And Urdu Muhammad Akram Khan The Islamic Foundation 3 Islamic Economics: Annonated Sources In English And Urdu Muhammad Akram Khan The Islamic Foundation Simon Archer, Riffat Ahmed Abdul 4 Islamic Finance: The New Regulatory Challenge John Wiley & Sons Karim Al-Jamiaus Sahi Sunan Tirmidhi: The Translation Of The Meaning Of Jami Tirmidhi, Muhammad Ibn Isa Darul Ishaat Tirmidhi 5 Al-Jamiaus Sahi Sunan Tirmidhi: The Translation Of The Meaning Of Jami Tirmidhi, Muhammad Ibn Isa Darul Ishaat Tirmidhi Encyclopaedia Of Islamic Philosophy Seyyed Hossein Nasr Suhail Academy 6 Encyclopaedia Of Islamic Philosophy Seyyed Hossein Nasr Suhail Academy A History Of Sufism In India Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi Suhail Academy 7 A History Of Sufism In India Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi Suhail Academy Encyclopedia Of Islamic Spirituality Seyyed Hossein Nasr Suhail Academy 8 Encyclopedia Of Islamic Spirituality Seyyed Hossein Nasr Suhail Academy IBA Centre for Excellence in Islamic Finance Library Resources Titles Book Name Author -

Cooper Collection

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives. Ref: MS 181 Title: Cooper Collection Scope: Documents, both published and unpublished, of an anti-semitic nature apparently compiled by an individual, thought to be F. T Cooper, a cartoonist associated with the Imperial Fascist League, and mainly of the 1930s. Dates: 1917-1954 (mainly 1930s) Level: Fonds Extent: 6 boxes Name of creator: F.T. Cooper Administrative / biographical history: This is a miscellaneous collection of ephemeral materials expressing a strongly anti- semitic viewpoint which appears to have belonged to an individual. It was purchased in February 1993 from a bookseller who had received it in a wooden trunk bearing the name 'Cooper'. Some of the items are inscribed 'F.T. Cooper', and the title 'Cooper Collection' therefore seems appropriate. F.T. Cooper was a cartoonist associated with the Imperial Fascist League, who issued a number of the pamphlets in the collection. The collection consists of both manuscript and printed material, some of the latter being rare, such as the English language version of World Service issued by the Nazis in the 1930s. It is divided into the following categories: Printed pamphlets Leaflets and ephemera Manuscripts and typescripts Newspapers and newsletters Certain other material has been subsequently added to this collection where considered appropriate (e.g. microfilm versions of serials in the Newspapers and newsletters section). Related collections: Fascism in Great Britain Collection Source: Purchased 1993 System of arrangement: By genre Subjects: Fascism - Great Britain; Anti-Semitism - Great Britain Names: Cooper, F.T.; Imperial Fascist League 1 Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: List based on the bookseller's catalogue COOPER COLLECTION MS 181/1 Printed Pamphlets 1. -

A Critical Examination of Ibn-Sina's Theory of the Conditional Syllogism

Sophia Perennis Vol. 1, Number 1, 2009 Iranian Institute of Philosophy Tehran/Iran A Critical Examination of Ibn-Sina’s Theory of the Conditional Syllogism Zia Movahed Professor at Iranian Institute of Philosophy Abstract: This paper will examine Ibn Sina’s theory of the Conditional Syllogism from a purely logical point of view, and will lay bare the principles he adopted for founding his theory, and the reason why the newly introduced part of his logic remained undeveloped and eventually was removed from the texts of logic in the later Islamic tradition. As a preliminary discussion, this paper briefly examines Ibn Sina's methodology and gives a short summary of the relevant principles of Aristotelian logic, before delving into the analysis of Ibn Sina's treatment of the conditional, which is the heart of the paper. This analysis explains Ibn Sina's theory of conditionals in systematic stages, explaining his motivation at each step and showing the weaknesses in his argument using the tools of modern symbolic logic. The paper concludes by mentioning a few of Ibn Sina's remarkable insights regarding conditionals. Key terms: Conditional Syllogism, Ibn Sina, Aristotelian Logic. Introduction After the publication of Ibn-Sina’s al-Shifa: al-Qiyas, edited by S. Zayed, Cairo, 1964, where Ibn-Sina presented most extensively his theory of the Number 1, Winter 2009 5 A Critical Examination of Ibn-Sina’s Theory conditional syllogism and, later on, the publication of Nabil Shehaby’s translaon of it into English in 19731 I think we have all we should have in hand to evaluate Ibn-Sina’s theory as it is, a theory Ibn-Sina regards as his important contribution to Aristotelian logic and as a new form of argument “unknown until now, which I myself discovered”2 (my translation). -

Sufism: Love and Wisdom

Sufism: Love and Wisdom The inner spiritual core of Islam has been the focus of Sufi practitioners and thinkers for hundreds of years. Those initiated into its mysteries have sometimes expressed those mysteries in ecstatic poetry in a symbolic language of love, as did Rumi, or sometimes in reasoned prose, as did Ibn Arabi. Sufism: Love and Wisdom contains essays by such renowned scholars as: Seyyed Hossein Nasr, William Chittick, Titus Burckhardt, Maria Massi Dakake, Reza Shah-Kazemi Angus Macnab, William Stoddart, Leo Schaya Martin Lings, René Guénon, and Frithjof Schuon. This book also contains several essays translated into English for the first time including Denis Gril and Éric Geoffroy and contributions from a new generation of interpreters of Sufism. About the Co-Editors Jean-Louis Michon Jean-Louis Michon is a traditionalist French scholar and art consultant who specializes in Islam in North Africa, Islamic art, and Sufism. His works include Autobiography of a Moroccan Sufi: Ahmad Ibn ‘Ajiba (1747-1809), Lights of Islam: Institutions, Cultures, Arts, and Spirituality in the Islamic City. Dr. Michon coordinated the rehabilitation of traditional handicrafts in Morocco which were seriously threatened by industrialization. World Wisdom Roger Gaetani Roger Gaetani is an editor and long-time student of Sufism, who spent five years in Morocco as a teacher. While there, he developed an interest in Sufism and met a number of traditional Sufi adherents and teachers, including ‘Abd as-Salam ad-Darqawi, a master of Koranic recitation and a direct descendant of the great Sufi Shaykh Mulay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi. Gaetani also spent two years in Saudi Arabia, where he taught at King Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah. -

Philosophical, Religious, Cultural, Historical / the Early British Perennialist Authors Compiled by William Stoddart, Createspace, 2019, 112 Pp

Annotations: Philosophical, Religious, Cultural, Historical / The Early British Perennialist Authors Compiled by William Stoddart, CreateSpace, 2019, 112 pp. Reviewed by Samuel Bendeck Sotillos …the encounter of the world religions was inevitable and, given the special needs of our time…positive…for ‘the greater glory of God’; in other words, not for the loss of souls, but for their salvation.1 – William Stoddart he title of this work will intrigue readers and cause them to wonder T how all these themes can be unified. William Stoddart (b. 1925) brings us not only the wisdom of having lived the integrative framework of the perennial philosophy and one of its divinely revealed paths, but also the broad panorama of human encounters as a wayfarer on the spiritual path. From the outset of the book Stoddart diagnoses the spiritual crisis of the present day and its historical antecedents with a striking tour de force: 1 William Stoddart, ‘Part II—Bernard Kelly,’ in Annotations: Philosophical, Religious, Cul- tural, Historical / The Early British Perennialist Authors (CreateSpace, 2019), p. 101. 190 SACRED WEB 46 Review: Annotations: Philosophical, Religious, Cultural, Historical – Samuel Bendeck Sotillos The first blow to traditional religion came with the 15th – century Renaissance. Three centuries later, an even more brutal blow was dealt by the so called ‘Enlightenment’. Worse still came in the 1960s with … Vatican II. Finally, the most lethal blow of all came with the ‘political correctness’ of the 21st century. The ‘end times’ are indeed cruel—but, come what may, religion cannot be extirpated from the heart of man. (p. 9) Stoddart informs readers of his orientation for his preparing this work: ‘The underlying philosophy of my Annotations is, of course, that of the Religio Perennis.’ ( p . -

Islamicbookstore.Com the Internet’S Largest Islamic Store Table of Contents

IslamicBookstore.com The Internet’s Largest Islamic Store Table of Contents The Holy Qur’an in Arabic 5 English Translations of the Qur’an 7 Qur’an Translations in Other Languages 11 Urdu Qur’an Translations and Tafseer 12 Commentaries, Tafsir of the Qur’an 13 Introductions to the Qur’an, Its Style, Themes, and Its Scientific Proofs 15 Qur’anic Language, Vocabulary, and Indexes 20 Arabic Language and Grammar 22 Dictionaries of the Arabic Language 27 Hadith Collections, Selections, and Sciences of Hadith 28 Sirah, the Life of the Prophet Muhammad 32 Biographies of the Prophets and the Companions 35 Aqeedah: Islamic Belief 38 The Unseen World and Dream Interpretations 44 The Last Day: Nature and Signs 45 Death and the Afterlife, Paradise and Hell 46 Funeral Rites, Islamic Wills and Inheritance 48 Islamic Studies, Courses for Adults 48 Fatwa Compilations 50 Salat - Daily Prayer and Purification 51 Ramadan, Fasting 53 Hajj, the Pilgrimage 54 Zakat, Charity in Islam 55 The Friday Prayer, the Mosque and Eid 55 Supplications, Dhikr, and Dua’a 56 Women Issues: Hijab, Dress, Medical etc. 58 Marriage, Courtship, Intimacy etc. 60 Parenting and Family Life in Islam 63 Muslim Baby Names 64 Nutrition and Cookbooks 65 Health and Medicine in Islam 65 Women Studies and Modernity 66 Morality, Manners, Etiquette, Sins, Repentance 67 Dawah, Knowledge and Education 73 Spiritual Development 75 Philosophy and Insights into the Divine 78 Books by Harun Yahya 79 Works of Imam al-Ghazali 82 Tasawwuf - Sufism 85 Islamic Culture and Arts and Science 93 Biographies -

A.K. Chesterton and the Problem of British Fascism, 1915-1973

A.K. CHESTERTON AND THE PROBLEM OF BRITISH FASCISM, 1915-1973. Luke LeCras Bachelor of Arts in History with Honours. THESIS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MURDOCH UNIVERSITY, AUGUST 2017 THESIS DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. .................................... Luke LeCras i ABSTRACT Fascist and extreme right-wing political movements in Britain have been the subject of enduring interest to historians since 1945, with the majority of works centring on the British Union of Fascists (BUF), a political party founded and led by Sir Oswald Mosley between 1932 and 1940. Despite the BUF’s failure to achieve levels of support on par with many fascist movements in continental Europe, there is now a sizeable body of historiography dealing with the party as a minor case within the study of European fascism and as a unique phenomenon of radical politics in interwar Britain. By comparison, little interest has been devoted to aspects of British fascism not connected to Mosley or the BUF. Moreover, extreme right movements operating in Britain since 1945 have largely been characterized as either a direct legacy of the interwar movement or an attempt to reform British fascism under a different guise. This thesis re-examines the continuity between the interwar and the post-war iterations of the extreme right in Britain by focusing on the ideas and activism of Arthur Kenneth (A.K) Chesterton. A high-ranking member of the BUF who made substantial contributions to the party’s propaganda, Chesterton split with Mosley in 1938 to pursue an independent career in extreme right-wing politics that persisted until his death in 1973. -

College of Optometrists Historical Books

College of Optometrists Rare and Historical Books Collection This document is an incomplete listing of the rare and historical books in the College Library’s Historical Collections 1 and 2. The annotations in this bibliographic catalogue are taken from the books themselves, the 1932, 1935 and 1957 BOA Library Catalogues, Albert, ‘ Sourcebook of Ophthalmology’, IBBO vols 1 & 2, various auction catalogues and booksellers catalogues and ongoing curatorial research. This list was begun by the BOA Librarian (1999-2007) Mrs Jan Ayres and has been continued by the BOA Museum Curator (1998- ) Mr Neil Handley. Date of current version: 12 February 2015 ABBOTT, T.K. Sight and touch: an attempt to disprove the received (or Berkeleian) theory of vision. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1864 A refutation of Berkley’s theory that the sight does not perceive distance, which is perceived by touch or by the locomotive faculty. Sir William de Wiveleslie Abney (1844-1920) The English physicist Sir William de Wiveleslie Abney (1843-190?) was one of the founders of modern photography. His interest in the theory of light, colour photography and spectroscopy spurred his investigations into colour vision. He entered the Royal Navy at the age of 17, retiring in 1881 with the rank of Captain. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1876 he was awarded the Rumford Medal in 1882 for his work on radiation. He was a pioneer in the chemistry of Photography. In 1892 he gave a lecture at the Royal Society of Arts on ‘Colour Blindness’ and in 1894 delivered the Tyndall Lectures at the Royal Institution on Colour Vision. -

Sophia Perennis

Del mismo editor: SOPHIA PERENNIS 1. Frithjof Schuon, Tras las huellas de la 32. Angus Macnab, España bajo la media luna. religión perenne. 33. Martin Lings, El secreto de Shakespeare. 2. Titus Burckhardt, Clave espiritual de la 34. Titus Burckhardt, El arte del Islam. astrología musulmana según Muhyu-dîn Lenguaje y significado. Ibn Arabî. 36. Shaykh al-Arabî ad-Dârqawî, Cartas de 3. Titus Burckhardt, Símbolos. un maestro sufí. 5. Jean Hani, El simbolismo del templo 37. ‘Abd ar-Rahmân al-Jâmî, Los hálitos de la cristiano. intimidad. 6. Frithjof Schuon, Castas y razas, seguido 38. Frédéric Portal, El simbolismo de los de Principios y criterios del arte universal . colores. 7. A. K. Coomaraswamy, Sobre la doctrina 40. Frithjof Schuon, Las perlas del peregrino. tradicional del arte. 41. El Zohar. Revelaciones del «Libro del 8. Louis Charbonneau-Lassay, Estudios Esplendor». sobre simbología cristiana. 42. Frithjof Schuon, El sol emplumado. 10. Khempo Tsultrim Gyamtso, Meditación Los indios de las praderas a través del sobre la vacuidad. arte y la filosofía. 13. Cantos pieles rojas. 43. Valmiki, El mundo está en el alma. 15. Bernard Dubant, Sitting Bull. Toro 44. L. Charbonneau-Lassay, El bestiario Sentado. «El último indio». de Cristo. Vol. I. 16. René Guénon, La metafísica oriental. 45. L. Charbonneau-Lassay, El bestiario 17. El jardín simbólico. Texto griego extraído de Cristo. Vol. II. del Clarkianus XI. 46. Julius Evola, El misterio del Grial. 19. Pierre Ponsoye, El Islam y el Grial. 47. Julius Evola, Metafísica del sexo. Estudio sobre el esoterismo del Parzival 48. Jean Hani, La Virgen Negra y el misterio de Wolfram von Eschenbach.