Reactions and Assessments: Educational Laboratory Theatre Project, 1966-70

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrity and Race in Obama's America. London

Cashmore, Ellis. "To be spoken for, rather than with." Beyond Black: Celebrity and Race in Obama’s America. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 125–135. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781780931500.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 05:30 UTC. Copyright © Ellis Cashmore 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 11 To be spoken for, rather than with ‘“I’m not going to put a label on it,” said Halle Berry about something everyone had grown accustomed to labeling. And with that short declaration she made herself arguably the most engaging black celebrity.’ uperheroes are a dime a dozen, or, if you prefer, ten a penny, on Planet SAmerica. Superman, Batman, Captain America, Green Lantern, Marvel Girl; I could fi ll the rest of this and the next page. The common denominator? They are all white. There are benevolent black superheroes, like Storm, played most famously in 2006 by Halle Berry (of whom more later) in X-Men: The Last Stand , and Frozone, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson in the 2004 animated fi lm The Incredibles. But they are a rarity. This is why Will Smith and Wesley Snipes are so unusual: they have both played superheroes – Smith the ham-fi sted boozer Hancock , and Snipes the vampire-human hybrid Blade . Pulling away from the parallel reality of superheroes, the two actors themselves offer case studies. -

Hallmark Collection

Hallmark Collection 20000 Leagues Under The Sea In 1867, Professor Aronnax (Richard Crenna), renowned marine biologist, is summoned by the Navy to identify the mysterious sea creature that disabled the steamship Scotia in die North Atlantic. He agrees to undertake an expedition. His daughter, Sophie (Julie Cox), also a brilliant marine biologist, disguised as a man, comes as her father's assistant. On ship, she becomes smitten with harpoonist Ned Land (Paul Gross). At night, the shimmering green sea beast is spotted. When Ned tries to spear it, the monster rams their ship. Aronnax, Sophie and Ned are thrown overboard. Floundering, they cling to a huge hull which rises from the deeps. The "sea beast" is a sleek futuristic submarine, commanded by Captain Nemo. He invites them aboard, but warns if they enter the Nautilus, they will not be free to leave. The submarine is a marvel of technology, with electricity harnessed for use on board. Nemo provides his guests diving suits equipped with oxygen for exploration of die dazzling undersea world. Aronnax learns Nemo was destined to be the king to lead his people into the modern scientific world, but was forced from his land by enemies. Now, he is hoping to halt shipping between the United States and Europe as a way of regaining his throne. Ned makes several escape attempts, but Sophie and her father find the opportunities for scientific study too great to leave. Sophie rejects Nemo's marriage proposal calling him selfish. He shows his generosity, revealing gold bars he will drop near his former country for pearl divers to find and use to help the unfortunate. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Sociology 3380-090, Race, Class, Gender and the American Dream Online, Fall 2021, University of Utah

Sociology 3380-090, Race, Class, Gender and the American Dream Online, Fall 2021, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office: Rm 429 Beh. Sci. Office Hours. Tuesday – Thursday 1pm – 5 pm or by appointment. Office Phone: 801-581-3075. Home Phone 801-278-6413 [email protected] Teaching Assistant; Sarah Dyer [email protected] Course Description This course is an introduction to the study of inequality in terms of race, class, ethnicity, gender and species from the standpoint of social science and sociology. It focuses on the social construction of stratification, inequality, oppression, race, class, ethnicity, gender, speciesism, environmental degradation, and how these phenomena intersect and influence identity and personal well-being. The class begins with an overview of society, basic sociological concepts and assumptions, methods, and the nature of social stratification and inequality. The course then highlights the many ways in which these factors interact to produce and perpetuate inequality, oppression, and suffering. It concludes with a discussion of present and future trends and possible strategies for effective social change that might ameliorate current conditions of injustice, prejudice, and discrimination. If given adequate notice, the syllabus may be changed and does not constitute a contract. My teaching assistant will be monitoring the discussion board and doing some of the grading. Course Goals The primary goal of this class is to give students a clear understanding of key sociological conceptions of power, authority, stratification, inequality, race, ethnicity, class, gender, intersectionality, and the nature of oppression. In emphasizing how these phenomena interact, students should acquire a better understanding of sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, ageism, speciesism, patriarchy, class bias, and environmental degradation. -

Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - the AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION

AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA CINEMA AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA The history of the African-American Cinema is a harsh timeline of racism, repression and struggle contrasted with film scenes of boundless joy, hope and artistic spirit. Until recently, the study of the "separate cinema" (a phrase used by historians John Kisch and Edward Mapp to describe the segregation of the mainstream, Hollywood film community) was limited, if not totally ignored, by writers and researchers. The uphill battle by black filmmakers and performers, to achieve acceptance and respect, was an ugly blot on the pages of film history. Upon winning his Best Actor Oscar for LILLIES OF THE FIELD (1963), Sidney Poitier accepted, on behalf of the countless unsung African-American artists, by acknowledging the "long journey to this moment." This emotional, heartbreaking and inspiring journey is vividly illustrated by the latest acquisition to the Belknap Collection for the Performing Arts - THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION. The valuable research material, housed in this collection, includes over 300 pressbooks (illustrated campaign and advertising catalogs sent to theatre owners), press kits (media packages including biographies, promotional essays and illustrations), programs and over 1000 photographs and slides. The journey begins with the blatant racism of D.W. Griffith's THE BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), a film respected as an epic milestone, but reviled as the blueprint for black film stereotypes that would appear throughout the 20th century. Researchers will follow African-American films through an extended period of stereotypical casting (SONG OF THE SOUTH, 1946) and will be dazzled by the glorious "All-Negro" musicals such as STORMY WEATHER (1943), ST.LOUIS BLUES (1958) and PORGY AND BESS (1959). -

An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: an Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film by Donald Bogle Dominique M

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-11-2011 An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film By Donald Bogle Dominique M. Hardiman Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Hardiman, Dominique M., "An Interactive Study Guide to Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Film By Donald Bogle" (2011). Research Papers. Paper 66. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 AN INTERACTIVE STUDY GUIDE TOMS, COONS, MULATTOS, MAMMIES, AND BUCKS: AN INTERPRETIVE HISTORY OF BLACKS IN AMERICAN FILM BY DONALD BOGLE Written by Dominique M. Hardiman B.S., Southern Illinois University, 2011 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters of Science Degree Department of Mass Communications & Media Arts Southern Illinois University April 2011 ii RESEARCH APPROVAL AN INTERACTIVE STUDY GUIDE TOMS, COONS, MULATTOS, MAMMIES, AND BUCKS: AN INTERPRETIVE HISTORY OF BLACKS IN AMERICAN FILM By Dominique M. Hardiman A Research Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in the field of Professional Media & Media Management Approved by: Dr. John Hochheimer, Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 11, 2011 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Research would not have been possible without the initial guidance of Dr. -

QUOTES of the MONTH: まかぬはえぬmakanutanewahaenu (Seeds That Aren’T Sown Can’T Grow.) Japanese Proverb “What You Think, You Become.” Gautama Buddha, Founder of Buddhism

MAY 2012 ALMANAC This almanac, a compilation of 33 calendars Chase’s Calendar of Events for updating isby Susan Curnow Breedlove c)2012 This is the month of the Budding Moon or Flower Moon, WabigoniGisiss in Ojibwe, Wuyue in Chinese, (皐月), Gogatsu(早苗) in Japanese Mai in French, Mayo in Spanish, Lab TsibHlisNtuj in Hmong The flowers of the month are the Lilly of the Valley and Hawthorne. The birthstone of the month is Emerald (Happiness) MAY IS AMERICAN INDIAN MONTH, ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN MONTH, RESPECT OUR ELDERS MONTH & NATIONAL FAMILY MONTH QUOTES OF THE MONTH: まかぬはえぬMakanutanewahaenu (Seeds that aren’t sown can’t grow.) Japanese proverb “What you think, you become.” Gautama Buddha, Founder of Buddhism “It does not require many words to speak the truth.” Chief Seattle, a prominent leader of the Suquamish Native American tribes in the 1800’s in what is now Washington state Tuesday, May 1.MAY DAY activities will be carried out throughout the world as this INTERNATIONAL WORKER'S DAY (LABOR DAY). BELTANE, one of the "Greater Sabbats" in the Wiccan year, observed, celebrating the fertility of spring and the greening of earth as it is each May 1st. The U.S. also observes LAW DAY with the theme this year “NO Courts, NO Justice, NO Freedom.” Today is LEI DAY in Hawaii, and SCHOOL PRINCIPAL'S DAY. HAITIAN HERITAGE MONTH honors General TouissaintLouverture ("The Black Napoleon") and the Haitian consensus reached in 1803 to fight Napoleon's forces for independence. The NEW ORLEANS JAZZ & HERITAGE FESTIVAL continues through May 6th. 1762-African American physician James Durham, born. -

Rating Guide 27 5P; 28 12P Comedy Gomez, Morticia and Their Natasha

park where the rides are designed with Elizabeth Hawthorne. (PG-13, 2:00) ’18 minimum safety for maximum fun. When SHOS-E 321 June 13 7:30a, TMC-E 327 a corporate mega-park opens nearby, June 1 5:15a, 10p; 9 11a; 17 6:15p; 20 D.C. and his loony crew of misfits must 7:45a; 28 2p; 29 4:30a, TMCX-E 328 adventurer and a botanist lead a Tibetan pull out all the stops to try and save the June 2 9:30a; 4 10p; 7 2:50p; 27 4:15p; A search for the legendary big-footed Yetis. day. Johnny Knoxville, Chris Pontius, 30 11:15a Dan Bakkedahl, Matt Schulze. (1:30) ’18 Abducted Suspense A war hero Forrest Tucker, Peter Cushing, Maureen Adventureland 555 Comedy-Drama 9 EPIX 380 June 13 6:30a, EPIX2 381 June takes matters into his own hands Connell, Richard Wattis. (1:30) ’57 A college grad takes a lowly job at an A FXM 384 June 10 4:30a, 11:50a; 16 7 5:40a, EPIXHIT 382 June 11 8:45a; 12 amusement park after his parents refuse when a kidnapper snatches his 8:05a; 25 8:20a young daughter during a home 11:50a; 27 9:35a; 28 6a to fund his long-anticipated trip to Europe. invasion. Scout Taylor-Compton, Daniel About a Boy 555 Comedy-Drama An An Actor Prepares Comedy After Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, Martin Joseph, Michael Urie, Najarra Townsend. irresponsible playboy becomes emotion- suffering a heart attack, a hard-drinking Starr, Kristen Wiig. -

And the Winner Is: Inviting Hollywood Into the Neuroscience Classroom

The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education (JUNE), Fall 2002, 1(1): A4-A17. And the Winner Is: Inviting Hollywood into the Neuroscience Classroom Eric P. Wiertelak Department of Psychology, Macalester College, Saint Paul, MN 55105 Both short excerpts from, and full-length presentation of neuroscience film series, features group discussion of feature films have been used with success in movies of perhaps more limited relevance to neuroscience. undergraduate instruction. Studies of such use of films has An additional goal of this article is provide the reader revealed that incorporation of film viewing within courses with initial resources for the selection of potential film titles can promote both content mastery and the development of for use in neuroscience education. Three extensive tables critical thinking skills. This article discusses and provides are included to provide a wide range of title suggestions examples of successful use of two methods that may be appropriate for use in activities such as the neuro-cinema, used to incorporate a variety of full-length feature films into the neuroscience film series, or for more limited use as neuroscience instruction. One, the "neuro-cinema" pairs short "clips" in classroom instruction. the presentation of a film featuring extensive neuroscience content with primary literature reading assignments, group Key Words: teaching methods; neuroscience education; discussion and writing exercises. The second, a Motion Pictures; films; movies. It is no secret that instructors across disciplines have long neuroscience education may also help students to made use of feature films and short "clips" from movies in recognize the many intellectual and vocational possibilities conjunction with classroom instruction. -

Trouble in Mind

The Author ALICE CHILDRESS (1916-1994) was celebrated in an obituary in Britain’s Guardian newspaper as someone who was regarded as “a champion of impoverished black P R E V I E W P R O G R A M M E people, who used her writing to chronicle the exploitation of African-Americans.” JACKIE MAXWELL STUDIO THEATRE, AUGUST 8 TO OCTOBER 9 Born in Charleston, South Carolina, she was raised in Harlem by her grandmother (the daughter of a slave). Childress dropped out of high school following the death of her grandmother and took a series of low-paying jobs in New York. In 1934 she married an actor named Alvin Childress, with whom she had a daughter. She later joined a New York amateur theatre group, American Negro Theater, where she gained experience in a wide variety of theatrical activity, including acting and TIM CARROLL, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | TIM JENNINGS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR playwriting. Her Broadway acting debut came in 1944 in Philip Yordan’s play Anna Lucasta, which, with an all-black cast, including her husband, ran for over two years at the Mansfield Theatre. Childress’s early plays, such asFlorence (1949), Just a Little NAFEESA MONROE, KIERA SANGSTER Simple (1950) and Gold Through the Trees (1952), were all produced in Harlem under the auspices of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts. Her next play, however, and GRAEME SOMERVILLE in Trouble in Mind, based in part on Childress’s own experience of racial stereotyping in theatre, moved south to Greenwich Village, where it opened on November 3, 1955 at the 200-seat Greenwich Mews Theatre. -

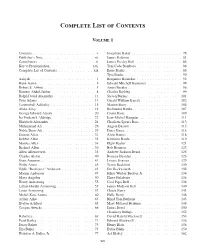

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents. v Josephine Baker . 78 Publisher’s Note . vii James Baldwin. 81 Contributors . xi James Presley Ball. 84 Key to Pronunciation. xvii Toni Cade Bambara . 86 Complete List of Contents . xix Ernie Banks . 88 Tyra Banks. 90 Aaliyah . 1 Benjamin Banneker . 92 Hank Aaron . 3 Edward Mitchell Bannister . 94 Robert S. Abbott . 5 Amiri Baraka . 96 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar . 8 Charles Barkley . 99 Ralph David Abernathy . 11 Steven Barnes . 101 Faye Adams . 14 Gerald William Barrax . 102 Cannonball Adderley . 15 Marion Barry . 104 Alvin Ailey . 18 Richmond Barthé. 107 George Edward Alcorn . 20 Count Basie . 109 Ira Frederick Aldridge. 22 Jean-Michel Basquiat . 111 Elizabeth Alexander . 24 Charlotta Spears Bass . 113 Muhammad Ali . 26 Angela Bassett . 115 Noble Drew Ali . 29 Daisy Bates. 116 Damon Allen . 31 Alvin Batiste . 118 Debbie Allen . 33 Kathleen Battle. 119 Marcus Allen . 34 Elgin Baylor . 121 Richard Allen . 36 Bob Beamon . 123 Allen Allensworth . 38 Andrew Jackson Beard. 125 Charles Alston . 40 Romare Bearden . 126 Gene Ammons. 41 Louise Beavers . 129 Wally Amos . 43 Tyson Beckford . 130 Eddie “Rochester” Anderson . 45 Jim Beckwourth . 132 Marian Anderson . 47 Julius Wesley Becton, Jr. 134 Maya Angelou . 50 Harry Belafonte . 136 Henry Armstrong . 53 Cool Papa Bell . 138 Lillian Hardin Armstrong . 55 James Madison Bell . 140 Louis Armstrong . 57 Chuck Berry . 141 Molefi Kete Asante . 60 Halle Berry . 144 Arthur Ashe . 63 Blind Tom Bethune . 145 Evelyn Ashford . 65 Mary McLeod Bethune . 148 Crispus Attucks . 66 James Bevel . 150 Chauncey Billups . 152 Babyface. 69 David Harold Blackwell . 153 Pearl Bailey . 71 Edward Blackwell .