DAB and the Switchover to Digital Radio in the United Kingdom Guy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Download the Music Market Access Report Canada

CAAMA PRESENTS canada MARKET ACCESS GUIDE PREPARED BY PREPARED FOR Martin Melhuish Canadian Association for the Advancement of Music and the Arts The Canadian Landscape - Market Overview PAGE 03 01 Geography 03 Population 04 Cultural Diversity 04 Canadian Recorded Music Market PAGE 06 02 Canada’s Heritage 06 Canada’s Wide-Open Spaces 07 The 30 Per Cent Solution 08 Music Culture in Canadian Life 08 The Music of Canada’s First Nations 10 The Birth of the Recording Industry – Canada’s Role 10 LIST: SELECT RECORDING STUDIOS 14 The Indies Emerge 30 Interview: Stuart Johnston, President – CIMA 31 List: SELECT Indie Record Companies & Labels 33 List: Multinational Distributors 42 Canada’s Star System: Juno Canadian Music Hall of Fame Inductees 42 List: SELECT Canadian MUSIC Funding Agencies 43 Media: Radio & Television in Canada PAGE 47 03 List: SELECT Radio Stations IN KEY MARKETS 51 Internet Music Sites in Canada 66 State of the canadian industry 67 LIST: SELECT PUBLICITY & PROMOTION SERVICES 68 MUSIC RETAIL PAGE 73 04 List: SELECT RETAIL CHAIN STORES 74 Interview: Paul Tuch, Director, Nielsen Music Canada 84 2017 Billboard Top Canadian Albums Year-End Chart 86 Copyright and Music Publishing in Canada PAGE 87 05 The Collectors – A History 89 Interview: Vince Degiorgio, BOARD, MUSIC PUBLISHERS CANADA 92 List: SELECT Music Publishers / Rights Management Companies 94 List: Artist / Songwriter Showcases 96 List: Licensing, Lyrics 96 LIST: MUSIC SUPERVISORS / MUSIC CLEARANCE 97 INTERVIEW: ERIC BAPTISTE, SOCAN 98 List: Collection Societies, Performing -

Vividata Brands by Category

Brand List 1 Table of Contents Television 3-9 Radio/Audio 9-13 Internet 13 Websites/Apps 13-15 Digital Devices/Mobile Phone 15-16 Visit to Union Station, Yonge Dundas 16 Finance 16-20 Personal Care, Health & Beauty Aids 20-28 Cosmetics, Women’s Products 29-30 Automotive 31-35 Travel, Uber, NFL 36-39 Leisure, Restaurants, lotteries 39-41 Real Estate, Home Improvements 41-43 Apparel, Shopping, Retail 43-47 Home Electronics (Video Game Systems & Batteries) 47-48 Groceries 48-54 Candy, Snacks 54-59 Beverages 60-61 Alcohol 61-67 HH Products, Pets 67-70 Children’s Products 70 Note: ($) – These brands are available for analysis at an additional cost. 2 TELEVISION – “Paid” • Extreme Sports Service Provider “$” • Figure Skating • Bell TV • CFL Football-Regular Season • Bell Fibe • CFL Football-Playoffs • Bell Satellite TV • NFL Football-Regular Season • Cogeco • NFL Football-Playoffs • Eastlink • Golf • Rogers • Minor Hockey League • Shaw Cable • NHL Hockey-Regular Season • Shaw Direct • NHL Hockey-Playoffs • TELUS • Mixed Martial Arts • Videotron • Poker • Other (e.g. Netflix, CraveTV, etc.) • Rugby Online Viewing (TV/Video) “$” • Skiing/Ski-Jumping/Snowboarding • Crave TV • Soccer-European • Illico • Soccer-Major League • iTunes/Apple TV • Tennis • Netflix • Wrestling-Professional • TV/Video on Demand Binge Watching • YouTube TV Channels - English • Vimeo • ABC Spark TELEVISION – “Unpaid” • Action Sports Type Watched In Season • Animal Planet • Auto Racing-NASCAR Races • BBC Canada • Auto Racing-Formula 1 Races • BNN Business News Network • Auto -

The Digitalisation of Radio

The digitalisation of radio How the United Kingdom has handled the rollout of digital radio – lessons for New Zealand. A report for the Robert Bell Travelling Scholarship University of Canterbury Kineta Knight May 2009 CONTENTS Introduction 3 DAB – an overview 5 Part One – New Zealand media figures react to DAB 6 Part Two – DAB in the United Kingdom DAB terminology 8 Introduction 9 Establishing DAB in the UK: the benefits 13 Barrier to not adopting DAB 16 Launching DAB 17 Cost of DAB 19 Logistics of starting up DAB 20 Promoting DAB 21 Consumer uptake of DAB sets 22 Downfalls of DAB 24 The infamous pulling-out GCap 28 Internet streaming vs. DAB 30 Part Three – Current state of DAB in the United Kingdom Introduction 32 How the recession has affected DAB 33 Channel 4 35 DRWG – the way forward 38 DAB’s future in the UK 40 DAB+ for the future? 42 Part Four – Would DAB+ work in New Zealand? 44 Conclusions and recommendations 46 Works cited 48 2 Introduction Digital technology is now at the forefront of international media, quickly leaving the analogue medium behind. With the evolution of television in New Zealand moving into the digital age, such as Sky Television and the introduction of Freeview, the switching of radio from analogue to a digital form promises to follow closely behind. The reason digital radio is of major interest in New Zealand is because the Government, along with a digital service provider and some of the nation’s major broadcasters, have been trialling a digital service. But, for New Zealand there are still uncertainties over which digital option to choose, how best to introduce it and control growth, what impact it will have on existing stations, and what will happen to the current market when new stations are established? New Zealand broadcasting and telecommunications company Kordia has already trialled a digital service, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), but the Government is yet to commit to a long-term rollout of the technology. -

Get Maximum Exposure to the Largest Number of Professionals in The

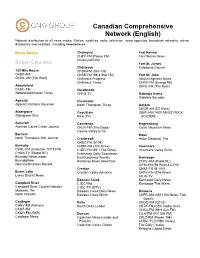

Canadian Comprehensive Network (English) National distribution to all news media. Dailies, weeklies, radio, television, news agencies, broadcast networks, online databases and websites, including newswire.ca. News Media Chetwynd Fort Nelson CHET-FM [Peace FM] Fort Nelson News Chetwynd Echo British Columbia Fort St. James Chilliwack Caledonia Courier 100 Mile House CFSR-FM (Star FM) CKBX-AM CKSR-FM (98.3 Star FM) Fort St. John CKWL-AM [The Wolf] Chilliwack Progress Alaska Highway News Chilliwack Times CHRX-FM (Energy 98) Abbotsford CKNL-FM (The Bear) CKQC-FM Clearbrook Abbotsford/Mission Times CFEG-TV Gabriola Island Gabriola Sounder Agassiz Clearwater Agassiz Harrison Observer North Thompson Times Golden CKGR-AM [EZ Rock] Aldergrove Coquitlam CKIR-AM [1400 AM EZ ROCK Aldergrove Star Now, The GOLDEN] Ashcroft Courtenay Hagensborg Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal CKLR-FM (The Eagle) Coast Mountain News Comox Valley Echo Barriere Hope North Thompson Star Journal Cranbrook Hope Standard, The CHBZ-FM (B104) Burnaby CHDR-FM (The Drive) Invermere CFML-FM (Evolution 107.9 FM) CJDR-FM (99.1 The Drive) Invermere Valley Echo CHAN-TV (Global BC) Cranbrook Daily Townsman Burnaby NewsLeader East Kootenay Weekly Kamloops BurnabyNow Kootenay News Advertiser CHNL-AM (Radio NL) New Westminster Record CIFM-FM (98 Point 3 CIFM) Creston CKBZ-FM (B-100) Burns Lake Creston Valley Advance CKRV-FM (The River) Lakes District News CFJC-TV Dawson Creek Kamloops Daily News Campbell River CJDC-AM Kamloops This Week Campbell River Courier-Islander CJDC-TV (NTV) Midweek, -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored Call Letters Market Station Name Format WAPS-FM AKRON, OH 91.3 THE SUMMIT Triple A WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRQK-FM AKRON, OH ROCK 106.9 Mainstream Rock WONE-FM AKRON, OH 97.5 WONE THE HOME OF ROCK & ROLL Classic Rock WQMX-FM AKRON, OH FM 94.9 WQMX Country WDJQ-FM AKRON, OH Q 92 Top Forty WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary WPYX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY PYX 106 Classic Rock WGNA-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY COUNTRY 107.7 FM WGNA Country WKLI-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 100.9 THE CAT Country WEQX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 102.7 FM EQX Alternative WAJZ-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY JAMZ 96.3 Top Forty WFLY-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY FLY 92.3 Top Forty WKKF-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY KISS 102.3 Top Forty KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary KZRR-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KZRR 94 ROCK Mainstream Rock KUNM-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COMMUNITY RADIO 89.9 College Radio KIOT-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COYOTE 102.5 Classic Rock KBQI-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM BIG I 107.9 Country KRST-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 92.3 NASH FM Country KTEG-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 104.1 THE EDGE Alternative KOAZ-AM ALBUQUERQUE, NM THE OASIS Smooth Jazz KLVO-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 97.7 LA INVASORA Latin KDLW-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM ZETA 106.3 Latin KKSS-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KISS 97.3 FM -

Rajar Q42004 National Stations

RAJAR Quarterly Summary of Radio Listening - Quarter 4, 2004 - NATIONAL STATIONS RELEASED AT 7.00AM THURSDAY JANUARY 27, 2005 KEY Quarter 4, 2004 in green Quarter 3, 2004 in blue Quarter 4, 2004 in pink % Change Y/Y and Q/Q for reach only * = less than 0.5% TERMS WEEKLY REACH: The number in thousands of the UK/area adult population who listen to a station for at least 5 minutes in the course of an average week. SHARE OF LISTENING: The percentage of total listening time accounted for by a station in the UK/area in an average week TOTAL HOURS: The overall number of hours of adult listening to a station in the UK/area in an average week. SAMPLE SIZE: Survey Period - Code Q (Quarter): 32,776 Adults 15+ / Code H (Half year) 63,646 Adults 15+ TOTAL HOURS (in thousands): All BBC Q4 03: 568985 Q3 04: 580393 Q4 04: 567674 TOTAL HOURS (in thousands): ALL COMMERCIAL Q4 03: 486848 Q3 04: 466008 Q4 04: 464351 STATION SURVEY REACH REACH REACH % CHANGE % CHANGE SHARE SHARE SHARE PERIOD 000 000 000 REACH Y/Y REACH Q/Q % % % Q4 03 Q3 04 Q4 04 04 vs 03 Q4 vs Q3 Q4 03 Q3 04 Q4 04 ALL RADIO Q 43915 43775 43816 -0.2% 0.1% 100.0 100.0 100.0 ALL BBC Q 32036 32514 32490 1.4% -0.1% 52.9 54.4 54.0 ALL BBC NETWORK RADIO Q 28032 28643 28429 1.4% -0.7% 42.0 43.5 43.0 BBC RADIO 1 Q 9440 10042 9926 5.1% -1.2% 7.7 8.6 8.2 BBC RADIO 2 Q 13151 13060 13305 1.2% 1.9% 16.0 16.1 16.4 BBC RADIO 3 Q 2192 2072 2100 -4.2% 1.4% 1.4 1.1 1.3 BBC RADIO 4 Q 9513 9422 9406 -1.1% -0.2% 11.5 11.3 11.5 BBC RADIO FIVE LIVE Q 6125 6398 5981 -2.4% -6.5% 4.4 4.9 4.3 BBC RADIO FIVE LIVE (inc -

Bbc One Hd Uk

UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO SD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV HD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 HD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 HD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE HD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY WITNESS FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY WITNESS SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ATLANTIC FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ATLANTIC SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 4SEVEN SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5SELECT SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5STAR SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5US SD UK: Entertainment: UK: ALIBI FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: ALIBI SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ALBA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC RED BUTTON SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BET SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS DRAMA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS JUSTICE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS REALITY SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHALLENGE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL HD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL SD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL EXTRA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: DAVE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: DAVE SD -

National Stationspdf

RAJAR DATA RELEASE Quarter 1, 2020 – May 14 th 2020 NATIONAL STATIONS STATIONS SURVEY REACH REACH REACH % CHANGE % CHANGE SHARE SHARE SHARE PERIOD '000 '000 '000 REACH Y/Y REACH Q/Q % % % Q1 19 Q4 19 Q1 20 Q1 20 vs. Q1 19 Q1 20 vs. Q4 19 Q1 19 Q4 19 Q1 20 ALL RADIO Q 48945 48136 48894 -0.1% 1.6% 100.0 100.0 100.0 ALL BBC Q 34436 33584 33535 -2.6% -0.1% 51.4 51.0 49.7 15-44 Q 13295 13048 13180 -0.9% 1.0% 35.2 35.5 34.4 45+ Q 21142 20535 20355 -3.7% -0.9% 60.2 59.4 57.9 ALL BBC NETWORK RADIO Q 31846 31081 30835 -3.2% -0.8% 44.8 45.0 43.4 BBC RADIO 1 Q 9303 8790 8915 -4.2% 1.4% 5.7 5.6 5.6 BBC RADIO 2 Q 15356 14438 14362 -6.5% -0.5% 17.4 17.0 16.3 BBC RADIO 3 Q 2040 2126 1980 -2.9% -6.9% 1.2 1.4 1.3 BBC RADIO 4 (INCLUDING 4 EXTRA) Q 11459 11416 11105 -3.1% -2.7% 13.1 13.4 12.9 BBC RADIO 4 Q 11010 10977 10754 -2.3% -2.0% 11.9 12.0 11.7 BBC RADIO 4 EXTRA Q 2238 2271 1983 -11.4% -12.7% 1.3 1.4 1.2 BBC RADIO 5 LIVE (INC. SPORTS EXTRA) Q 5550 5522 5330 -4.0% -3.5% 3.5 3.7 3.4 BBC RADIO 5 LIVE Q 5403 5412 5219 -3.4% -3.6% 3.4 3.5 3.3 BBC RADIO 5 LIVE SPORTS EXTRA Q 708 914 601 -15.1% -34.2% 0.1 0.2 0.1 BBC 6 MUSIC Q 2515 2487 2556 1.6% 2.8% 2.4 2.4 2.4 1XTRA FROM THE BBC H 1050 987 986 -6.1% -0.1% 0.4 0.4 0.4 BBC ASIAN NETWORK UK H 536 519 543 1.3% 4.6% 0.2 0.2 0.3 BBC WORLD SERVICE Q 1478 1377 1346 -8.9% -2.3% 0.7 0.8 0.7 BBC LOCAL/REGIONAL Q 7857 7500 7798 -0.8% 4.0% 6.6 6.0 6.3 Source RAJAR / Ipsos MORI / RSMB RAJAR DATA RELEASE Quarter 1, 2020 – May 14 th 2020 NATIONAL STATIONS PAGE 2 STATIONS SURVEY REACH REACH REACH % CHANGE % CHANGE SHARE SHARE SHARE PERIOD '000 '000 '000 REACH Y/Y REACH Q/Q % % % Q1 19 Q4 19 Q1 20 Q1 20 vs. -

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION Sept2015 Ontario-Only

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION Sept2015 ROSE highlight = ER Online Ontario-Only (Eng Fre) GREEN highlight = Manual Station Vernacular Lang Type Format City Prov Owner,Firm Main Contact Title Phone Number Email CHLK-FM Lake 88.1 E FM Music; News; Pop Music Perth ONT (Perkin) Brian & Norm Wright Brian Perkin Station Manager +1 (613) 264-8811 [email protected] CKDR-AM 92.7 FM E FM Adult Contemporary Dryden ONT Via FM Acadia Broadcasting 807-223-2355 [email protected] CKDR-FM 92.7 FM E FM Adult Contemporary Dryden ONT CJRN-AM CJRN E AM Music; News Niagara Falls ONT AM 710 Radio Inc. Liam Myers Program Director +1 (905) 356-6710 Ext. 231 [email protected] CHAM-AM 820 CHAM E AM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; [email protected] Music; News; Sports [email protected], CKLH Rep: [email protected] Hamilton ONT Drew Keith Program Director +1 (905) 574-1150 Ext. 421 CKLH-FM 102.9 K-Lite FM E FM Music; News [email protected] CHRE Rep: CKOC-AM Oldies 1150 AM Music; News; Oldies [email protected] CIQM-FM 97-5 London's EZ Rock E FM Music; News; Pop Music CJBK-AM News Talk 1290 CJBK E AM News; Sports London ONT Astral Media Al Smith Program Director +1 (519) 686-6397 [email protected] CKSL-AM Funny 1410 E AM Music; News; Oldies CJBX-FM News Talk 1290 CJBK E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; London ONT Astral Media Chris Harding Music +1 (519) 691-2403 [email protected] Music; News CJOT-FM Boom 99.7 E FM Music; News; Rock Music Ottawa ONT Astral Media Sarah Cummings Program Director +1 (613) 225-1069 Ext. -

Nielsen BDS - Stations Monitored 7/12/2018

Nielsen BDS - Stations Monitored 7/12/2018 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary CJED Buffalo, NY 105.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary DAC Networks WESTWOODONE - ADULT CONTEMPORARY Adult Contemporary DHAC Networks WESTWOODONE - HOT AC Adult Contemporary KAFE Seattle-Tacoma, WA KAFE 104.1 FM Adult Contemporary KALC Denver, CO ALICE 105.9 FM Adult Contemporary KAMX Austin, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KATY Riverside-San Bernardino, CA 101.3 FM THE MIX Adult Contemporary KBBK Lincoln, NE B107.3 Adult Contemporary KBBY Oxnard-Ventura, CA 95.1 KBBY Adult Contemporary KBEE Salt Lake City, UT B98.7 Adult Contemporary KBIG Los Angeles, CA 104.3MYfm Adult Contemporary KBPA Austin, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KBZN Salt Lake City, UT THE BREEZE Adult Contemporary KCBS Los Angeles, CA JACK FM Adult Contemporary KCDA Spokane, WA 103.1 KCDA Adult Contemporary KCIX Boise, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KCKC Kansas City, MO-KS KC 102.1 Adult Contemporary KCYZ Des Moines, IA NOW 1051 Adult Contemporary KDGE Dallas-Ft. Worth, TX STAR 102.1 Adult Contemporary KDMX Dallas-Ft. Worth, TX 102.9 NOW Adult Contemporary KDRB Des Moines, IA 100.3 THE BUS Adult Contemporary KDRF Albuquerque, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KESZ Phoenix, AZ 99.9 KEZ Adult Contemporary KEZA Fayetteville-Springdale, AR MAGIC 107.9 Adult Contemporary KEZK St. Louis, MO 102.5 KEZK Adult Contemporary KEZN Palm Springs, CA 103.1 SUNNY FM Adult Contemporary KEZR San Jose, CA MIX 106.5 TODAY'S BEST MIX Adult Contemporary KFBZ Wichita, KS 105.3 THE BUZZ Adult Contemporary KGBX Springfield, MO 105.9 KGBX Adult Contemporary KGMX Lancaster-Palmdale, CA KMIX 106-3 Adult Contemporary KHMX Houston-Galveston, TX MIX 96.5 KHMX Adult Contemporary KHTI Riverside-San Bernardino, CA HOT 103.9 Adult Contemporary KIMN Denver, CO MIX 100 Adult Contemporary KIOI San Francisco, CA STAR 101.3 Adult Contemporary KISC Spokane, WA KISS 98.1 Adult Contemporary KISQ San Francisco, CA 98.1 THE BREEZE Adult Contemporary KJAQ Seattle-Tacoma, WA 96.5 JACK FM Adult Contemporary KJKK Dallas-Ft. -

Quarterly Summary of Radio Listening Part 2

Rajar 1ST 2006 3/5/06 12:54 pm Page 1 QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 26th March 2006 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 49,377,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period ’000 % per head per listener ’000 TSA % ALL RADIO Q 44297 90 21.3 23.8 1054084 100.0 ALL BBC Q 32568 66 11.8 17.9 583654 55.4 All BBC Network Radio Q 28391 57 9.5 16.4 466731 44.3 BBC Local/Regional Q 10381 21 2.4 11.3 116924 11.1 ALL COMMERCIAL Q 30424 62 9.1 14.8 449529 42.6 All National Commercial Q 13145 27 2.2 8.4 110321 10.5 All Local Commercial Q 24654 50 6.9 13.8 339208 32.2 Other Listening Q 2882 6 0.4 7.3 20900 2.0 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI * Audiences in Local analogue areas excluded from ‘All BBC Network Radio’ and ‘All National Commercial’ totals. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Embargoed until 7.00 am Enquiries to: RAJAR, Paramount House, 162-170 Wardour Street, London W1F 8ZX Thursday 11th May 2006 Telephone: 020 7292 9040 Facsimile: 020 7292 9041 e mail: [email protected] Internet: www.rajar.co.uk ©Rajar 2006. Any use of information in this press release must acknowledge the source as “RAJAR/Ipsos MORI.” Rajar 1ST 2006 3/5/06 12:54 pm Page 2 QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 26th March 2006 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 49,377,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period ’000 % per head per