Mapping Digital Media: United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities As Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field

Celebrities as Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field Ellen Watts Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics 2018 Declaration I, Ellen Watts, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Ellen Watts September 17, 2018. 2 Abstract The ability of celebrities to become influential political actors is evident (Marsh et al., 2010; Street 2004; 2012, West and Orman, 2003; Wheeler, 2013); the process enabling this is not. While Driessens’ (2013) concept of celebrity capital provides a starting point, it remains unclear how celebrity capital is exchanged for political capital. Returning to Street’s (2004) argument that celebrities claim to speak for others provides an opportunity to address this. In this thesis I argue successful exchange is contingent on acceptance of such claims, and contribute an original model for understanding this process. I explore the implicit interconnections between Saward’s (2010) theory of representative claims, and Bourdieu’s (1991) work on political capital and the political field. On this basis, I argue celebrity capital has greater explanatory power in political contexts when fused with Saward’s theory of representative claims. Three qualitative case studies provide demonstrations of this process at work. Contributing to work on how celebrities are evaluated within political and cultural hierarchies (Inthorn and Street, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Mendick et al., 2018; Ribke, 2015; Skeggs and Wood, 2011), I ask which key factors influence this process. -

SUDEP Action Keeping in Touch Making Every Epilepsy Death Count January 2018

Knowledge saves lives #Prevent21 Find out more at: www.sudep.org/prevent21 SUDEP Action Keeping in touch Making every epilepsy death count January 2018 Hello there ... I hope that you will feel uplifted by the good award of an MBE this month to Dr Rohit newsSUDEP we are able to share. The pages here Shankar. Recent coverage in Channel 4 are full of stories ofAc couragetion and inspirational News and Sky One has boosted the charity, people,Making as wellevery poems epilepsy and stories death of personalcount as we start 2018, with our innovations linked grief from those we support and work to falling deaths; at a time when the NHS and alongside. others are finally recognising SUDEP and epilepsy deaths as an issue requiring attention. We have set a date for our upcoming National Conference - a great chance Boosted by all this good news, we have for supporters to meet and hear what’s launched PREVENT21 our new campaign happeningSUDEP at the charity. focused on the 21 deaths a week, and what Action can be done to stop deaths and help families News about our successful appeal to fund a now. clinicalMaking trial every into a wearableepilepsy epilepsy death detectioncount device, has led directly to development Finally, with this newsletter, there is a funding for the next five years - the feedback survey. We are looking to revamp largest funding to a researcher working the newsletter and learn more about what on SUDEP in the UK since the charity was is important to you. Is it a new format? Or founded. -

East Tower Inspiration Page 6

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online East Tower inspiration Page 6 AUGUST 2014 • Issue 4 TV news celebrates Remembering Great (BBC) 60 years Bing Scots Page 2 Page 7 Page 8 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC TV news celebrates its 60th birthday Sixty years ago, the first ever BBC TV news bulletin was aired – wedged in between a cricket match and a Royal visit to an agriculture show. Not much has changed, has it? people’s childhoods, of people’s lives,’ lead to 24-hour news channels. she adds. But back in 1983, when round the clock How much!?! But BBC TV news did not evolve in news was still a distant dream, there were a vacuum. bigger priorities than the 2-3am slot in the One of the original Humpty toys made ‘A large part of the story was intense nation’s daily news intake. for the BBC children’s TV programme competition and innovation between the On 17 January at 6.30am, Breakfast Time Play School has sold at auction in Oxford BBC and ITV, and then with Channel 4 over became the country’s first early-morning TV for £6,250. many years,’ says Taylor. news programme. Bonhams had valued the 53cm-high The competition was evident almost ‘It was another move towards the sense toy at £1,200. immediately. The BBC, wary of its new that news is happening all the time,’ says The auction house called Humpty rival’s cutting-edge format, exhibited its Hockaday. -

The Leveson Inquiry Into the Cultures, Practices And

For Distribution to CPs THE LEVESON INQUIRY INTO THE CULTURES, PRACTICES AND ETHICS OE THE PRESS WITNESS STATEMENT OE JAMES HANNING I, JAMES HANNING of Independent Print Limited, 2 Derry Street, London, W8 SHF, WILL SAY; My name is James Hanning. I am deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday and, with Francis Elliott of The Times, co-author of a biography of David Cameron. In the course of co-writing and updating our book we spoke to a large number of people, but equally I am very conscious that I, at least, dipped into areas in which I can claim very little specialist knowledge, so I would emphasise that in several respects there are a great many people better placed to comment and much of what follows is impressionistic. I hope that what follows is germane to some of the relationships that Lord Justice Leveson has asked witnesses to discuss. I hesitate to try to draw a broader picture, but I hope that some conclusions about the disproportionate influence of a particular sector of the media can be drawn from my experience. My interest in the area under discussion in the Third Module stems from two topics. One is in David Cameron, on whose biography we began work in late 2005, soon after Cameron became Tory leader. The second is an interest in phone hacking at the News of the World. Tory relations with Murdoch Since early 2007, the Conservative leadership has been extremely keen to ingratiate itself with the Murdoch empire. It is striking how it had become axiomatic that the support of the Murdoch papers was essential for winning a general election. -

The True Story of Mission to Hell Page 4

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online The true story of Mission to Hell Page 4 August 2015 • Issue 4 Trainee Oh! What operators a lovely reunite – Vietnam War TFS 1964 50 years on Page 6 Page 8 Page 12 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC Departments Annual report highlights ‘better’ for BBC challenge move to Salford The BBC faces a challenge to keep all parts of the audience happy at the same time as efficiency targets demand that it does less. said that certain segments of society were more than £150k and to trim the senior being underserved. manager population to around 1% of But this pressing need to deliver more and the workforce. in different ways comes with a warning that In March this year, 95 senior managers Delivering Quality First (DQF) is set to take a collected salaries of more than £150k against bigger bite of BBC services. a target of 72. The annual report reiterates that £484m ‘We continue to work towards these of DQF annual savings have already been targets but they have not yet been achieved,’ achieved, with the BBC on track to deliver its the BBC admitted, attributing this to ‘changes Staff ‘loved the move’ from London to target of £700m pa savings by 2016/17. in the external market’ and the consolidation Salford that took place in 2011 and The first four years of DQF have seen of senior roles into larger jobs. departments ‘are better for it’, believes Peter Salmon (pictured). a 25% reduction in the proportion of the More staff licence fee spent on overheads, with 93% of Speaking four years on from the biggest There may be too many at the top, but the the BBC’s ‘controllable spend’ now going on ever BBC migration, the director, BBC gap between average BBC earnings and Tony content and distribution. -

Why Journalism Matters a Media Standards Trust Series

Why Journalism Matters A Media Standards Trust series Lionel Barber, editor of the Financial Times The British Academy, Wednesday 15 th July These are the best of times and the worst of times if you happen to be a journalist, especially if you are a business journalist. The best, because our profession has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to report, analyse and comment on the most serious financial crisis since the Great Crash of 1929. The worst of times, because the news business is suffering from the cyclical shock of a deep recession and the structural change driven by the internet revolution. This twin shock has led to a loss of nerve in some quarters, particularly in the newspaper industry. Last week, during a trip to Colorado and Silicon Valley, I was peppered with questions about the health of the Financial Times . The FT was in the pink, I replied, to some surprise. A distinguished New York Times reporter remained unconvinced. “We’re all in the same boat,” he said,”but at least we’re all going down together.” My task tonight is not to preside over a wake, but to make the case for journalism, to explain why a free press and media have a vital role to play in an open democratic society. I would also like to offer some pointers for the future, highlighting the challenges facing what we now call the mainstream media and making some modest suggestions on how good journalism can not only survive but thrive in the digital age. Let me begin on a personal note. -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

Hacking Affair Is Not Over – but What Would a Second Leveson Inquiry Achieve?

7/10/2019 Hacking affair is not over – but what would a second Leveson inquiry achieve? Academic rigour, journalistic flair Hacking affair is not over – but what would a second Leveson inquiry achieve? July 25, 2014 3.57pm BST Author John Jewell Director of Undergraduate Studies, School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University On we go. Ian Nicholson/PA In the latest episode in the long-running saga that is the phone hacking affair, Dan Evans, a former journalist at the News of the World and Sunday Mirror, has received a 10 month suspended sentence after being convicted of two counts of phone hacking, one of making illegal payments to officials, and one of perverting the course of justice. Coming so soon after the conviction of Andy Coulson and the acquittal of Rebekah Brooks and others, one could be forgiven for assuming that the whole phone hacking business is now done and dusted. Not a bit of it. As Julian Petley has written: “Eleven more trials are due to take place involving 20 current or former Sun and News of the World journalists, who are accused variously of making illegal payments to public officials, conspiring to intercept voicemail and accessing data on stolen mobile phones.” We also learned in June that Scotland Yard had officially told Rupert Murdoch of their intention to interview him as part of their inquiry into allegations of crime at his British newspapers. The Guardian revealed that Murdoch was first contacted in 2013, but the police ceded to his lawyers’ request that any interrogation should wait until the Coulson–Brooks trial had finished. -

Out of This World!

EDITION 2 WINTER 2019 INSIDER STATS: Just how is Oxfordshire leading the way? NEWS IN BRIEF: Get the latest on Oxfordshire’s globally- OUT OF facing economy CHIEF EXEC’S UPDATE: THIS Looking back on 2018 and leading into 2019 WORLD! With a vision of ‘a world empowered by actionable information from space’ and a mission to ‘deliver effective satellite-based solutions for global challenges’ – the Harwell Campus-based Open Cosmos ticks many of the boxes underlining Oxfordshire’s global space credentials, as highlighted in autumn 2017’s science and innovation audit. Part of a space cluster that employees 950 and autonomous vehicles and technologies be delivered in under 12 months – this after people working across 89 academic, private underpinning quantum computing. signing a $2 million ‘Pioneer’ contract with and public space-related organisations the ESA. If fully-utilised, the audit suggested the at Harwell Campus (cover photo), Open technologies could be worth in the region ‘Call to Orbit’ winners are set to be awarded Cosmos is without doubt one of its stand-out of £180billion to the UK economy by 2030 – access to Open Cosmos’ ‘orbit readiness’ players and has made quite the impact since around six per cent of the global economy in programme for free, allowing projects to launching in July 2015, whilst its co-founder these technologies. The UK space industry’s go from concept to ‘orbit readiness’ in just and current CEO was at the prestigious target is an ambitious 10% of the global space three months. It’s hoped a variety of space Entrepreneur First incubator programme. -

Statement: Ofcom's Plan of Work 2021/22

Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 Making communications work for everyone Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 – Welsh translation STATEMENT: Publication Date: 26 March 2021 Contents Section 1. Chief Executive’s foreword 1 2. Overview 3 3. Our goals and priorities for 2021/22 9 4. Delivering good outcomes for consumers across the UK 31 Annex A1. What we do 37 A2. Project work for 2021/2022 39 Plan of Work 2021/22 1. Chief Executive’s foreword Ofcom is the UK’s communications regulator, with a mission to make communications work for everyone. We serve the interests of consumers and businesses across the UK’s nations and regions, through our work in mobile and fixed telecoms, broadcasting, spectrum, post and online services. Over the past year we have learned that being connected is everything. High-quality, reliable communications services have never mattered more to people’s lives. But as consumers shift their habits increasingly online, our communications sectors are transforming fast. It is an exciting moment for our industries and for Ofcom as a regulator - it requires long-term focus alongside speed and agility in response to change. Against this backdrop our statement sets out our detailed goals for the coming financial year, and how we plan to achieve them. On telecoms, Ofcom has just confirmed a new long-term framework for investment in gigabit- capable fixed networks. In the coming year, we will shift our focus to support delivery against this programme, alongside investment and innovation in 5G and new mobile infrastructure. Following legislation in Parliament, we will put in place new rules to hold operators to account for the security and resilience of their networks. -

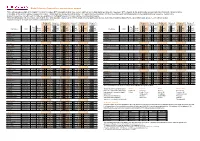

Digital Television Transmitters: Pre-Switchover Network

Digital Television Transmitters: pre-switchover network This leaflet provides details of the Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) transmitters which have not yet switched over to fully-digital operation (the 'low power' DTT network). Detailed information on post-switchover transmitter characteristics is available on the Ofcom website at www.ofcom.org.uk. Transmitters are grouped according to the ITV1 region that they broadcast, which will determine each transmitter's place in the digital switchover sequence. Details of the programme services carried in each multiplex are available on the Digital Television Group's website, www.dtg.org.uk/retailer. While this information is believed to be correct at the time of preparation, changes to the DTT network will occur, particularly as more transmitters switch to digital. For the latest information, please see the Ofcom website, www.ofcom.org.uk, or Digital UK's website, www.digitaluk.co.uk. Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva Avg. Avg. Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Site Name NGR Aerial Site Name NGR Aerial Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Height Offset Height Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Anglia Tyne Tees -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media.