The Digitalisation of Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 | Curated Proceedings 1 FOREWORD

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 CURATED PROCEEDINGS “Are we reaching all New Zealanders?” Exploring the Role, Benefits, Challenges & Potential of Ethnic Media in New Zealand Edited by Evangelia Papoutsaki & Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014. Curated Proceedings is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Ethnic Migrant Media Forum, Unitec Institute of Technology Thursday 13 November, 8.45am–5.45pm Unitec Marae, Carrington Road, Mt Albert Auckland, New Zealand The Introduction and Discussion sections were blind peer-reviewed by a minimum of two referees. The content of this publication comprises mostly the proceedings of a publicly held forum. They reflect the participants’ opinions, and their inclusion in this publication does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the editors, ePress or Unitec Institute of Technology. This publication may be cited as: Papoutsaki, E. & Kolesova, E. (Eds.) (2017). Ethnic migrant media forum 2014. Curated proceedings. Auckland, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://unitec. ac.nz/epress/ Cover design by Louise Saunders Curated proceedings design and editing by ePress Editors: Evangelia Papoutsaki and Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Photographers: Munawwar Naqvi and Ching-Ting Fu Contact [email protected] www.unitec.ac.nz/epress Unitec Institute of Technology Private Bag 92025, Victoria Street West Auckland 1142 New Zealand ISBN 978-1-927214-20-6 Marcus Williams, Dean of Research and Enterprise (Unitec) opens the forum -

Aid to Channel 4 Linked to Digital Switchover Invitation to Submit Comments Pursuant to Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty

C 137/16EN Official Journal of the European Union 4.6.2008 STATE AID — UNITED KINGDOM State aid C 13/08 (ex N 589/07) — Aid to Channel 4 linked to digital switchover Invitation to submit comments pursuant to Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty (Text with EEA relevance) (2008/C 137/10) By means of the letter dated 2 April 2008 reproduced in the authentic language on the pages following this summary, the Commission notified the United Kingdom of its decision to initiate the procedure laid down in Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty concerning the proposed financial support to Channel 4 to enable it to meet the costs of digital switchover. Interested parties may submit their comments on the measure in respect of which the Commission is initi- ating the procedure within one month of the date of publication of this summary and the following letter, to: European Commission Directorate-General for Competition State Aid Registry SPA 3 6/5 B-1049 Brussels Fax (32-2) 296 12 42 These comments will be communicated to the United Kingdom. Confidential treatment of the identity of the interested party submitting the comments may be requested in writing, stating the reasons for the request. TEXT OF SUMMARY The UK authorities accept that the notified measure constitutes an aid within the meaning of Article 87(1) of the Treaty. They argue however that the measure is compatible with the Treaty by virtue of Article 86(2), having regard to the Commission's 1 PROCEDURE Communication ( ) on the application of the State aid rules in relation to public service broadcasting (‘the Communication’) and the three particular criteria according to which the compati- The measures on which the Commission has opened the proce- bility of aid of this nature falls to be judged, namely, definition, dure laid down in Article 88(2) was brought to the Commis- entrustment and proportionality. -

Transforming the Way We Listen to Radio… ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS 2003

UBC MEDIA GROUP PLC ANNUAL REPORT UBC AND 2003 MEDIA ACCOUNTS REPORT PLC ANNUAL GROUP Transforming the way we listen to radio… ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2003 UBC MEDIA GROUP PLC 50 LISSON STREET LONDON NW1 5DF T. 020 7453 1600 F. 020 7723 6132 www.ubcmedia.com PRINCIPAL SUBSIDIARIES Unique is the largest independent Classic Gold Digital is one of Unique Facilities operates UBC’s Unique Interactive specialises in the producer of customised audio the most successful ‘gold’ radio analogue and digital radio facilities development and sale of software content in the UK. The company formats in the UK. Classic Gold and provides broadcast services for the management and delivery ranks as a leading supplier of both Digital is broadcast on both for both the Group’s internal use of media content to both the commissioned programmes to the analogue and digital platforms, and for external clients. analogue and digital radio sectors. BBC and syndicated programmes and ranks amongst the largest to the commercial radio sector. formats on digital radio. PRINCIPAL JOINT VENTURES UBC holds a 50% interest in UBC is a member of the MXR Oneword Radio. The Sony Radio consortium, which operates Academy Award-winning station regional digital radio multiplexes is the only national commercial covering North East and North digital radio station dedicated West England, the West Midlands, to the spoken word. South Wales and the Severn Estuary and Yorkshire. Group Turnover Operating Profit/(Loss)* 2001– 2003 2001– 2003 (£million) (£'000) 10.32 9.19 73 6.18 -210 -519 01 02 03 *Operating profit/(loss) before 01 02 03 goodwill and development. -

AREC.Info Newsletter January 2020

Monthly newsletter of Amateur Radio Emergency Communications JANUARY 2020 AREC .info CIMS, Third Edition NATIONAL DIRECTOR The Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) 3rd edition represents New Zealand’s official framework Happy New Year! I hope you all have or are having to achieve effective co-ordinated incident management an enjoyable break over the holiday season. across responding agencies. From 1 July 2020 the 3rd edition replaces all previous versions of CIMS. I would like to thank all our AREC volunteers for the last 12 months. AREC is reliant on your voluntary More information, and links to copies of the new document can be found here efforts to keep our repeaters and equipment https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/resources/coordinated- running and to provide the services to our SAR and incident-management-system-cims-third-edition/ emergency and community partners. ZL4SB Recognised AREC support of a number of public events throughout the country service the purpose as both David Stevenson ZL4SB was recognised for 40-years of AREC exercises and training as well as providing a service at a LandSAR event in Dunedin during November. public service. Again, thanks again for your willing participation. Lindsey Ross, AREC Deputy Director (and MC on the night) commented “it is great to see how our members Thanks go to Soren Low for implementing the Tait skills and dedication make a real difference to the EnableFleet online radio programming system. This organisations we work with”. has been deployed in conjunction with LandSAR More here https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/40- under our Service Level Agreement with them to years-communications enable nationally consistent programming of the TM/TP9300 radio fleet. -

The BBC's Use of Spectrum

The BBC’s Efficient and Effective use of Spectrum Review by Deloitte & Touche LLP commissioned by the BBC Trust’s Finance and Strategy Committee BBC’s Trust Response to the Deloitte & Touche LLPValue for Money study It is the responsibility of the BBC Trust,under the As the report acknowledges the BBC’s focus since Royal Charter,to ensure that Value for Money is the launch of Freeview on maximising the reach achieved by the BBC through its spending of the of the service, the robustness of the signal and licence fee. the picture quality has supported the development In order to fulfil this responsibility,the Trust and success of the digital terrestrial television commissions and publishes a series of independent (DTT) platform. Freeview is now established as the Value for Money reviews each year after discussing most popular digital TV platform. its programme with the Comptroller and Auditor This has led to increased demand for capacity General – the head of the National Audit Office as the BBC and other broadcasters develop (NAO).The reviews are undertaken by the NAO aspirations for new services such as high definition or other external agencies. television. Since capacity on the platform is finite, This study,commissioned by the Trust’s Finance the opportunity costs of spectrum use are high. and Strategy Committee on behalf of the Trust and The BBC must now change its focus from building undertaken by Deloitte & Touche LLP (“Deloitte”), the DTT platform to ensuring that it uses its looks at how efficiently and effectively the BBC spectrum capacity as efficiently as possible and uses the spectrum available to it, and provides provides maximum Value for Money to licence insight into the future challenges and opportunities payers.The BBC Executive affirms this position facing the BBC in the use of the spectrum. -

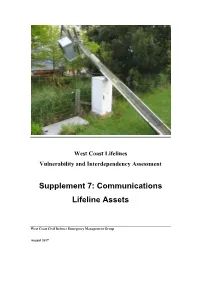

Communications Lifeline Assets

West Coast Lifelines Vulnerability and Interdependency Assessment Supplement 7: Communications Lifeline Assets West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group August 2017 IMPORTANT NOTES Disclaimer The information collected and presented in this report and accompanying documents by the Consultants and supplied to West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group is accurate to the best of the knowledge and belief of the Consultants acting on behalf of West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group. While the Consultants have exercised all reasonable skill and care in the preparation of information in this report, neither the Consultants nor West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group accept any liability in contract, tort or otherwise for any loss, damage, injury or expense, whether direct, indirect or consequential, arising out of the provision of information in this report. This report has been prepared on behalf of West Coast Civil Defence Emergency Management Group by: Ian McCahon BE (Civil), David Elms BA, MSE, PhD Rob Dewhirst BE, ME (Civil) Geotech Consulting Ltd 21 Victoria Park Road Rob Dewhirst Consulting Ltd 29 Norwood Street Christchurch 38A Penruddock Rise Christchurch Westmorland Christchurch Hazard Maps The hazard maps contained in this report are regional in scope and detail, and should not be considered as a substitute for site-specific investigations and/or geotechnical engineering assessments for any project. Qualified and experienced practitioners should assess the site-specific hazard potential, including the potential for damage, at a more detailed scale. Cover Photo: Telecommunications cabinet hit by fallen power pole, Kaikoura earthquake 2016. Photo from Chorus. West Coast Lifelines Vulnerability and Interdependency Assessment Supplement 7: Communications Lifeline Assets Contents 1 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................. -

Contact Information for BSA Callers

Contact information for BSA callers Our website has links to the main broadcasters’ websites and contact details (see Broadcaster Links). Links to the broadcasters’ online complaints forms appear under Formal Complaint to the Broadcaster/'If you are ready to make a complaint to the broadcaster now'. ABLE (captioning and audio description service) www.able.co.nz Advertising Standards Authority (help line) 0800 234 357 deals with complaints about advertisements [email protected] / www.asa.co.nz APRA (The Australasian Performing Right Assn) 0800 692 772 issues licences for businesses to play recorded www.apra.co.nz music in public Births, Deaths and Marriages 0800 22 52 52 copy of birth certificate required BSA freephone number 0800 366 996 Coalition for Better Broadcasting 021 666297 advocates for higher standards & better content www.betterbroadcasting.co.nz Complaints agencies: Complaint Line for a list of all agencies dealing with complaints www.complaintline.org.nz Consumer Affairs 04 474 2750 deals with scams www.consumeraffairs.govt.nz/scams information on how to complain for consumers www.consumeraffairs.govt.nz/for- consumers/how-to-complain Copyright: Copyright Council of New Zealand www.copyright.org.nz Ministry of Business, Innovation and www.med.govt.nz/business/intellectual- Employment (MBIE) property/copyright Department of Building and Housing 0800 737 666 PO Box 10729 Wellington 6143 Freeview channels not working: 0800 373 384 (Freeview 0800 number) Going Digital www.goingdigital.co.nz Fair Go NO phone calls Private Bag fax: -

Addition of Heart Extra to the Multiplex Is Therefore Likely to Increase Significantly the Appeal of Services on Digital One to This Demographic

Radio Multiplex Licence Variation Request Form This form should be used for any request to vary a local or national radio multiplex licence, e.g: • replacing one programme or data service with another • adding a programme or data service • removing a programme or data service • changing the Format description of a programme service • changing a programme service from stereo to mono • changing a programme service's bit-rate Please complete all relevant parts of this form. You should submit one form per multiplex licence, but you should complete as many versions of Part 3 of this form as required (one per change). Before completing this form, applicants are strongly advised to read our published guidance on radio multiplex licence variations, which can be found at: http://licensing.ofcom.org.uk/radio-broadcast- licensing/digital-radio/radio-mux-changes/ Part 1 – Details of multiplex licence Radio multiplex licence: DM01 National Commercial Licensee: Digital One Contact name: Glyn Jones Date of request: 15 January 2016 1 Part 2 – Summary of multiplex line-up before and after proposed change(s) Existing line-up of programme services Proposed line-up of programme services Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ short-form description (kbps)/ Mono short-form (kbps)/ Mono Coding (H description Coding (H or F) or F) Absolute Radio 80F M Absolute Radio 80F M Absolute 80s 80F M Absolute 80s 80F M BFBS 80F M BFBS 80F M Capital XTRA 112F JS Capital XTRA 112F JS Classic FM 128F JS Classic FM 128F JS KISS 80F M KISS 80F -

Mediametrie 126 000 Radio Ile De France Survey

PRESS RELEASE Levallois, 25th April 2019 MEDIAMETRIE 126 000 RADIO ILE DE FRANCE SURVEY Radio Audience in France: January-March 2019 Mediametrie publishes radio audience results, in metropolitan France over the December 31 to March 31 2019 period, measured on a population of 3,931 individuals aged of 13 years and over. The audience results focus on the “Monday-Friday” time base created by excluding Low Activity Days (LAD), days for which the activity rate is less than 55%. Over the previous period of January to March 2018, 3 LAD were identified : Monday December 31, Tuesday January 1st, Wednesday January 2. Characteristics of the period during the week (Monday-Friday) September – January – March January- March December 2019 2019 2018 Number of weekdays of the wave (including LADs) 65 80 65 Number of Low Activity Days 3 2 3 Number of school holidays 15 10 15 Activity rate excluding LADs (in %) (1) 75.0 75.7 75.2 1) Activity rate: share of employed individuals having carried out their professional activity on the same day as the interview. Radio Audience, population aged of 13 years and over (Monday-Friday) January – March 2019 September – December 2018 January- March 2018 TSL AQH AQH Cume Cume TSL AQH AQH Cume Cume TSL AQH AQH Cume Cume h/m % 000 % 000 h/mn % 000 % 000 h/mn % 000 % 000 n 5h - 24h 10.0 1.002 74.1 7.470 2h33 9.9 1.000 71.4 7.188 2h39 10.4 1.052 75.0 7.549 2h39 7h - 9h 20.2 2.032 42.0 4.228 0h58 20.7 2.089 42.2 4.247 0h59 20.1 2.026 41.7 4 201 0h58 This press release presents the intermediate results of audience in Ile-de-France, published over the first 8 weeks of reference period September-December, 2018. -

Completed Acquisition by Global Radio Uk Ltd of Gcap Media Plc

COMPLETED ACQUISITION BY GLOBAL RADIO UK LTD OF GCAP MEDIA PLC UNDERTAKINGS TO BE GIVEN BY GLOBAL RADIO UK LTD TO THE OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING PURSUANT TO SECTION 73 OF THE ENTERPRISE ACT 2002 WHEREAS: (a) On 6 June 2008 Global acquired GCAP; (b) It appears to the OFT that, as a consequence of that transaction, a relevant merger situation has been created in the UK; (c) The OFT has a duty to refer a completed merger to the CC for further investigation where it believes that it is or may be the case that the creation of that merger situation has resulted or may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the UK for goods or services; (d) Under section 73 of the Act the OFT may, instead of making such a reference and for the purpose of remedying, mitigating or preventing the substantial lessening of competition concerned or any adverse effect which may be expected to result from it, accept undertakings to take such action as it considers appropriate, from such of the parties concerned as it considers appropriate, in particular having regard to the need to achieve as comprehensive a solution as is reasonable and practicable to the substantial lessening of competition and any adverse effects resulting from it; (e) The OFT considers that, in the absence of appropriate undertakings, it would be under a duty to refer the acquisition of GCAP to the CC; and (f) The OFT further considers that the undertakings given below by Global are appropriate to remedy, mitigate or prevent the substantial lessening of competition, or any adverse effect which has or may have resulted from it, or may be expected to result from it, as specified in the Decision. -

Virgin Mobile Holdings (Uk)

A copy of this document, comprising listing particulars relating to Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc (the Company) prepared solely in connection with the proposed offer to certain institutional and professional investors (the Global Offer) of ordinary shares (the Ordinary Shares) in the Company in accordance with the Listing Rules made under section 74 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), has been delivered for registration to the Registrar of Companies in England and Wales pursuant to section 83 of FSMA. Application has been made to the UK Listing Authority for the ordinary share capital of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc to be admitted to the Official List of the UK Listing Authority and to the London Stock Exchange for such share capital to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities. It is expected that admission to listing and trading will become effective and that unconditional dealings will commence at 8.00 a.m. on 26 July 2004. All dealings in Ordinary Shares prior to the commencement of unconditional dealings will be on a ‘‘when issued’’ basis and of no effect if Admission does not take place and will be at the sole risk of the parties concerned. The Directors of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc, whose names appear on page 8 of this document, accept responsibility for the information contained in this document. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case), the information contained in this document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information.