Digital Broadcasting: Review of Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Radio Network

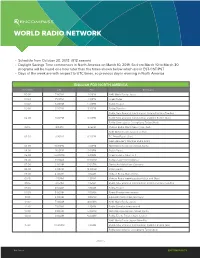

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 | Curated Proceedings 1 FOREWORD

Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014 CURATED PROCEEDINGS “Are we reaching all New Zealanders?” Exploring the Role, Benefits, Challenges & Potential of Ethnic Media in New Zealand Edited by Evangelia Papoutsaki & Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Ethnic Migrant Media Forum 2014. Curated Proceedings is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Ethnic Migrant Media Forum, Unitec Institute of Technology Thursday 13 November, 8.45am–5.45pm Unitec Marae, Carrington Road, Mt Albert Auckland, New Zealand The Introduction and Discussion sections were blind peer-reviewed by a minimum of two referees. The content of this publication comprises mostly the proceedings of a publicly held forum. They reflect the participants’ opinions, and their inclusion in this publication does not necessarily constitute endorsement by the editors, ePress or Unitec Institute of Technology. This publication may be cited as: Papoutsaki, E. & Kolesova, E. (Eds.) (2017). Ethnic migrant media forum 2014. Curated proceedings. Auckland, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://unitec. ac.nz/epress/ Cover design by Louise Saunders Curated proceedings design and editing by ePress Editors: Evangelia Papoutsaki and Elena Kolesova with Laura Stephenson Photographers: Munawwar Naqvi and Ching-Ting Fu Contact [email protected] www.unitec.ac.nz/epress Unitec Institute of Technology Private Bag 92025, Victoria Street West Auckland 1142 New Zealand ISBN 978-1-927214-20-6 Marcus Williams, Dean of Research and Enterprise (Unitec) opens the forum -

Review of Content Regulation Models

Issues facing broadcast content regulation MILLWOOD HARGRAVE LTD. Authors: Andrea Millwood Hargrave, Geoff Lealand, Paul Norris, Andrew Stirling Disclaimer The report is based on collaborative desk research conducted for the New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority over a two month period. Issue date November 2006 © Broadcasting Standards Authority, New Zealand Contents Aim and Scope of this Report..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 4 A: Introduction............................................................................................................. 6 Background............................................................................................................. 6 Definitions............................................................................................................... 9 What is the justification for regulation?.................................................................... 9 Protective content regulation: an overview............................................................ 10 Proactive content regulation: an overview............................................................. 12 Co-regulation and self-regulation........................................................................... 12 Technological changes and convergence.............................................................. 15 Differences in devices.......................................................................................... -

Cable Tv Scrolling Software Free Download

Cable tv scrolling software free download Movies; Songs Playing randomly and sequence; Religious Video(Bhajan); YouTube Live Streaming and Video Play; Serial Daily Sop Episode. Cable TV Software for broadcasting of TV Channel with various Locations like Internet TV, IPTV, and Cable Operator LCO for Local TV Channel, MSO Multi. Download Scrolling Software For Cable Tv - best software for Windows. Cable Player: Cable Player is a Entry Level digital video player for cable TV operators. A/V Broadcast System for Cable TV is a professional and reliable digital video broadcast software designed for cable TV operators. With A/V Scrolling & Animated Ad: displays ad crawlers at the any position of the screen. visit on web - contact No. + Cable TV Software, Media On Air software, Tv. It's a free all-in-one application for all of your entertainment needs. Search and download over songs directly to your PC, or listen over+ radio & TV Scrolling & Animated Ad: displays ad crawlers at the any position of the screen. Cable Player is a Entry Level digital video player for cable TV operators. Built-in titler with Easy-to-create scrolls and special effects like. Top/Bottom Scrolling Ad, Visual Ad, Live/Recorded Shows, slot booking. tv, tv advertising job description, local cable tv advertising software free download, tv. You want cable tv player software or broadcasting software for TV possibility for using as digital signage software along with smooth scrolls or ad scrolling from. Mx player cable tv software free download found at. TV Channel Automation Playout software - For Cable TV Channel RTF Scrolling in Titler. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

Tvnz Teletext

TVNZ TELETEXT YOUR GUIDE TO TVNZ TELETEXT INFORMATION CONTENTS WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved 4 New PAGE GUIDE 5 NEW FUNCTIONS AND FEATURES 6 CAPTIONING 7 ABOUT TVNZ TELETEXT 8 HOW TO USE TVNZ TELETEXT 9-10 HISTORY OF TVNZ TELETEXT 11 FAQ 12-13 Contact detailS 14 WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT It’s all available Your free service for up-to-the-minute news and information whenever you on your television need it – 24 hours a day, all year round. at the push of From news and sport to weather, a button travel, finance, TV listings and lifestyle information – it’s all available on your television, at the push of a button. 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved If you’ve looked at TVNZ Teletext recently and couldn’t find what you expected, don’t worry. To make the service easier and more logical to use we’ve reorganised a little. Your favourite content is still there – but in a different place. The reason is simple. We have a limited number of pages available, but need to show more information than ever. Previously, TVNZ Teletext had similar information spread across many pages unnecessarily. We’ve reorganised to keep similar pages together. For example, all news content is now grouped together, as is all sport content. You may also notice that the branding has changed slightly. Teletext is still owned and run by TVNZ, just as it always has been, we are now just reflecting this through the name - TVNZ Teletext. Now more than ever it will be a service that represents the integrity, neutrality and editorial independence you expect from New Zealand’s leading broadcaster. -

Broadcasting Standards in New Zealand

APRIL 2016 BROADCASTING STANDARDS IN NEW ZEALAND FOR RADIO, FREE-TO-AIR-TELEVISION & PAY TELEVISION DEVELOPED BY BROADCASTERS AND THE BSA AND ISSUED TO TAKE EFFECT FROM 1 APRIL 2016 In the case of any inconsistency between this Codebook and any predating BSA material such as codes, practice notes and advisory opinions, this Codebook will prevail. BROADCASTING STANDARDS IN NEW ZEALAND BROADCASTING STANDARDS AUTHORITY - TE MANA WHANONGA KAIPAHO LEVEL 2 | 119 GHUZNEE STREET PO BOX 9213 | WELLINGTON 6141 | NEW ZEALAND (04) 382 9508 | FREEPHONE: 0800 366 996 WWW.BSA.GOVT.NZ 1 / Broadcasting Standards Authority CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 03 THE FREE-TO-AIR The Broadcasting Standards Authority 04 TELEVISION CODE 32 Broadcasters 05 Standard 1 – Good Taste and Decency 35 Freedom of Expression 06 Standard 2 – Programme Information 35 Choice and Control 07 Standard 3 – Children’s Interests 36 Standards, Guidelines and Commentary 08 Standard 4 – Violence 36 Definitions 09 Standard 5 – Law and Order 36 Standard 6 – Discrimination and Denigration 37 COMMENTARY ON Standard 7 – Alcohol 37 Standard 8 – Balance 39 THE STANDARDS 10 Standard 9 – Accuracy 39 Standard 10 – Privacy 41 THE RADIO CODE 22 Standard 11 – Fairness 41 Standard 1 – Good Taste and Decency 25 Standard 2 – Programme Information 25 THE PAY Standard 3 – Children’s Interests 25 TELEVISION CODE 42 Standard 4 – Violence 26 Standard 1 – Good Taste and Decency 45 Standard 5 – Law and Order 26 Standard 2 – Programme Information 45 Standard 6 – Discrimination and Denigration 26 Standard 3 – Children’s -

Research in the Spotlight What Am I Discovering?

RESEARCH IN THE SPOTLIGHT WHAT AM I DISCOVERING? side of the world to measure the effects of poi on UNINEWS highlights some of the University physical and cognitive function in a clinical trial. research milestones that have hit the I wanted to discover how science and culture headlines in the past couple of months. might meet, and what they might say to each other about a weight orbiting on the end of a FISHING string. A study that exposed six decades of Working between the Centre for Brain widespread under reporting and dumping of Research and Dance Studies, the first round of marine fish has been covered extensively in an assessor-blind randomised control trial has the media. Lead researcher Dr Glenn Simmons just concluded. Forty healthy adults over 60 from the New Zealand Asia Institute at the years old participated in a month of International Business School appeared on Nine To Noon, Poi lessons (treatment group) or Tai Chi lessons Paul Henry, Radio Live, NewsHub and One (control group), and underwent a series of News, and was quoted in print and online. The pre- and post-tests measuring things like research, part of a decade-long, international balance, upper limb range of motion, bimanual project to assess the total global marine catch, coordination, grip strength, and cognitive put the true New Zealand catch at 2.7 times flexibility. Feedback from the participants official figures. after their International Poi lessons has been exciting: “Positive on flexibility, stress release, coordination and concentration. Totally, totally GRADUATION positive. Mental and physical.” “I am able to AGING GRACEFULLY use my left wrist more freely, and I am focusing The story of 84-year-old Nancy Keat, oldest better. -

Palmerston North Radio Stations

Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Whanganui (Bastia Hill) Mainstream Radio 87.6 FM and Palmerston rock(1990s- 2018 Hauraki North (Wharite) 2010s) Palmerston Full service iwi 89.8 FM Kia Ora FM Unknown Unknown North (Wharite) radio Palmerston Contemporary 2QQ, Q91 FM, 90.6 FM ZM 1980s North (Wharite) hits ZMFM Palmerston Christian 91.4 FM Rhema FM Unknown North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Adult 92.2 FM More FM 1986 2XS FM North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Contemporary 93.0 FM The Edge 1998 Country FM North (Wharite) Hit Radio Palmerston 93.8 FM Radio Live Talk Radio Unknown Radio Pacific North (Wharite) Palmerston 94.6 FM The Sound Classic Rock Unknown Solid Gold FM North (Wharite) Palmerston 95.4 FM The Rock Rock Unknown North (Wharite) Palmerston Hip Hop and 97.0 FM Mai FM Unknown North (Wharite) RnB Classic Hits Palmerston Adult 97.8 FM The Hits 1938 97.8 ZAFM, North (Wharite) contemporary 98FM, 2ZA Palmerston 98.6 FM The Breeze Easy listening 2006 Magic FM North (Wharite) Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Radio Palmerston 99.4 FM Campus radio Unknown Radio Massey Control North (Wharite) Palmerston 104.2 FM Magic Oldies 2014 Magic FM North (Wharite) Vision 100 Palmerston 105.0 FM Various radio Unknown Unknown FM North (Kahuterawa) Palmerston Pop music (60s- 105.8 FM Coast 2018 North (Kahuterawa) 1970s) 107.1 FM George FM Palmerston North Dance Music Community 2XS, Bright & Radio Easy, Classic 828 AM Trackside / Palmerston North TAB Unknown Hits, Magic, TAB The Breeze Access Triple Access Community Nine, 999 AM Palmerston North Unknown Manawatu radio Manawatu Sounz AM Pop Palmerston 1548 AM Mix music (1980s- 2005 North (Kahuterawa) 1990s) Palmerston North Radio Stations New Zealand Low Power FM Radio Station Database (Current List Settings) Broadcast Area: Palmerston North Order: Ascending ( A-Z ) Results: 5 Stations Listed. -

European SME Expertise in 5G and Beyond COMPANY PROFILES

This material has been designed and printed with support from the Full5G project and the NetWorld2020 SME Working Group. The Full5G Project has received funding by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Programme under the grant agreement number: 856777. European The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission SME Expertise cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. The NetWorld2020 SME Working Group and the NetWorld2020 in 5G and Beyond European Technology Platform cannot be held responsible for the information provided by the SMEs and for the quality of their potential contribution. More information at www.networld2020.eu/sme-support Co-funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union Co-funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union SME MEMBERS Citypassenger France INTEGRASYS Spain INTERINNOV France Martel GmbH Switzerland Nextworks s.r.l. Italy USEFUL LINKS Oledcomm France QUOBIS NETWORKS Spain Satelio IOT Services Spain Find the SME you need Seven Solutions S.L. Spain www.networld2020.eu/find-the-sme-you-need/ NetWorld2020 SME support www.networld2020.eu/sme-support NetWorld2020 European Technology Platform www.networld2020.eu 5G Public-Private Partnership www.5g-ppp.eu This document is released in June 2020 by the NetWorld2020 SME Working Group, with support from the Full5G project, from the NetWorld2020 European Technology Platform, and from the 5G Infrastructure Association. JACQUES MAGEN NICOLA CIULLI interinnov Nextworks Chair of the Vice-chair of the SME Working Group SME Working Group EDITORIAL I can hardly believe that this June 2020 edition of the “SME I am very happy to join our SME WG Chair, Jacques Magen, in brochure” is already the 4th annual edition. -

NZL FM Master List to Oct18

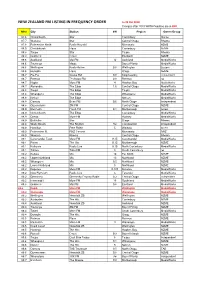

NEW ZEALAND FM LISTING IN FREQUENCY ORDER to 29 Oct 2018 Changes after 2019 WRTH Deadline are in RED MHz City Station kW Region Owner/Group 87.6 Christchurch Star Canterbury Rhema 87.7 Wanaka Star Central Otago Rhema 87.8 Palmerston North Radio Hauraki Manawatu NZME 88.0 Christchurch Flava Canterbury NZME 88.3 Taupo Star Taupo Rhema 88.3 Gisborne Coast Eastland NZME 88.6 Auckland Mai FM 10 Auckland MediaWorks 88.6 Tauranga Magic Bay of Plenty MediaWorks 88.6 Wellington Radio Active 0.5 Wellington Student 88.6 Dunedin Flava Otago NZME 88.7 Pio Pio Cruise FM 0.8 King Country Independent 88.7 Rotorua Te Arawa FM 0.8 Rotorua Iwi 88.7 Napier More FM 4 Hawkes Bay MediaWorks 88.7 Alexandra The Edge 1.6 Central Otago MediaWorks 88.8Taupo The Edge Taupo MediaWorks 88.8 Whanganui The Edge Whanganui MediaWorks 88.8 Nelson The Edge Nelson MediaWorks 88.8 Oamaru Brian FM 0.6 North Otago Independent 88.8 Queenstown ZM-FM Central Otago NZME 88.9 Blenheim Fresh FM 0.1 Marlborough Access 88.9 Christchurch The Edge Canterbury MediaWorks 88.9 Orewa More FM Rodney MediaWorks 88.9 Balclutha Star Otago Rhema 89.0 Waihi Beach The Rhythm 8w Coromandel Independent 89.0 Hamilton Free FM89 5 Waikato Access 89.0 Palmerston N. RNZ Concert Manawatu RNZ 89.0 Wanaka Rhema Central Otago Rhema 89.1 Coromandel Town More FM 0.15 Coromandel MediaWorks 89.1 Picton The Hits 0.15 Marlborough NZME 89.1 Kaikoura Radio Live 0.15 North Canterbury MediaWorks 89.1 Timaru Tahu FM 5 South Canterbury Iwi 89.2 Kaitaia Mix 10 Far North NZME 89.2 Upper Northland Mix 10 Northland NZME 89.2 -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide