Twins and Metatheatre in Plautus' Amphitryon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

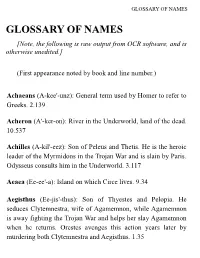

Odyssey Glossary of Names

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

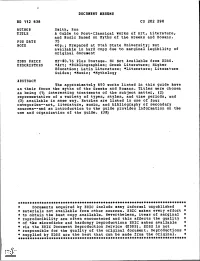

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

More Than Laughter in Plautus's Amphitryon Plautus's Amphitryon Is

More than Laughter in Plautus’s Amphitryon Plautus’s Amphitryon is an anomaly among extant Roman comedies, because it is the one surviving example of a play in which gods appear alongside mortal characters. In Amphitryon the term tragicomoedia (tragicomedy) appears for the first time in Latin literature to describe this blending of comedy and tragedy, and it is the god Mercury who coins the term in the play’s prologue. However, while modern scholarship lacks other examples of tragicomedy, both literary references and south Italian vase painting provide evidence for a much older tradition that blended comedy and tragedy, a tradition that can be traced back in literature to the mimes of Epicharmus of Syracuse in the fifth century, the hilarotragoedia of Rhinthon in fourth-century Syracuse, and the so-called phlyakes vases of southern Italy. So Plautus’s Amphitryon, written and performed perhaps around 200 B.C., was not a novelty. Indeed, the play’s topic, focusing as it does on the conception of Heracles through Jupiter’s sexual adventure with Alcmena, was perhaps one of the most well-known myths about one of the most well-known heroes in the Greco-Roman world. Since the cast of Amphitryon includes two gods, a hero and his wife (who is mentioned in Homer), the play presents a group of beings different from the slaves, pimps, and foolish young lovers of Plautus’s other plays. With divine and heroic characters, Amphitryon delivers comedy in a different register. On the one hand it is funny to hear the god Mercury talk and behave like a comic slave; and, as Christenson has argued, the audience would have found it humorous to watch a male actor in drag play the part of pregnant Alcmena. -

Homer's Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon

Homer’s Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon Epic and Mythology The Homeric Epics are probably the oldest Greek literary texts that we have,1 and their subject is select episodes from the Trojan War. The Iliad deals with a short period in the tenth year of the war;2 the Odyssey is set in the period covered by Odysseus’ return from the war to his homeland of Ithaca, beginning with his departure from Calypso’s island after a 7-year stay. The Trojan War was actually the material for a large body of legend that formed a major part of Greek myth (see Introduction). But the narrative itself cannot be taken as a mythographic one, unlike the narrative of Hesiod (see ch. 1.3) - its purpose is not to narrate myth. Epic and myth may be closely linked, but they are not identical (see Introduction), and the distance between the two poses a particular difficulty for us as we try to negotiate the the mythological material that the narrative on the one hand tells and on the other hand only alludes to. Allusion will become a key term as we progress. The Trojan War, as a whole then, was the material dealt with in the collection of epics known as the ‘Epic Cycle’, but which the Iliad and Odyssey allude to. The Epic Cycle however does not survive except for a few fragments and short summaries by a late author, but it was an important source for classical tragedy, and for later epics that aimed to fill in the gaps left by Homer, whether in Greek - the Posthomerica of Quintus of Smyrna (maybe 3 c AD), and the Capture of Troy of Tryphiodoros (3 c AD) - or in Latin - Virgil’s Aeneid (1 c BC), or Ovid’s ‘Iliad’ in the Metamorphoses (1 c AD). -

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts Battle of the Greeks and Amazons Temple of Apollo at Phigaleia (Bassai) Greek, late 5th c. B.C. The Mausoleion at Halikarnassos Greek, ca. 360-340 B.C. Myth: The Amazons lived in the northern limits of the known world. They were warrior women who fought from horseback usually with bow and arrows, but also with axe and spear. Their shields were crescent shaped. They destroyed the right breast of young Amazons, to facilitate use of the bow. The Attic hero Theseus had joined Herakles on his expedition against them and received the Amazon Antiope (or Hippolyta) as his share of the spoils of war. In revenge, the Amazons invaded Attica. In the subsequent battle Antiope was killed. This battle was represented in a number of works, notably the metopes of the Parthenon and the shield of the Athena Parthenos, the great cult statue by Pheidias that stood in the Parthenon. Symbolically, the battle represents the triumph of civilization over barbarism. Battle of the Gods and Giants Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon (Zeus battling Giants) Greek, ca. 180 B.C. Myth: The giants, born of Earth, threatened Zeus and the other gods, and a fierce struggle ensued, the so-called Gigantomachy, or battle of the gods and giants. The giants were defeated and imprisoned below the earth. This section of the frieze from the altar shows Zeus battling three giants. The myth may reflect an event of prehistory, the arrival ca. 2000 B.C. of Greek- speaking invaders, who brought with them their own gods, whose chief god was Zeus. -

Achilles in the Underworld: Iliad, Odyssey, and Aethiopis Anthony T

EDWARDS, ANTHONY T., Achilles in the Underworld: "Iliad, Odyssey", and "Aethiopis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 26:3 (1985:Autumn) p.215 Achilles in the Underworld: Iliad, Odyssey, and Aethiopis Anthony T. Edwards I HE ACTION of Arctinus' Aethiopis followed immediately upon T the Iliad in the cycle of epics narrating the war at Troy. Its central events were the combat between Achilles and the Ama zon queen Penthesilea, Achilles' murder of Thersites and subsequent purification, and Achilles' victory over the Ethiopian Memnon, lead ing to his own death at the hands of Apollo and Paris. In his outline of the Aethiopis, Proclus summarizes its penultimate episode as fol lows: "Thetis, arriving with the Muses and her sisters, mourns her son~ and after this, snatching (allap1Tauao-a) her son from his pyre, Thetis carries him away to the White Island (AevK7) "1iuo~)." Thetis removes, or 'translates', Achilles to a distant land-an equivalent to Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed - where he will enjoy eternally an existence similar to that of the gods.! Unlike the Aethiopis, the Iliad presents no alternative to Hades' realm, not even for its hero: Achil les, who has learned his fate from his mother (9.410-16),foresees his arrival there (23.243-48); and in numerous references elsewhere to Achilles' death, the Iliad never arouses any alternative expectation.2 1 For Proclus' summary see T. W. Allen, ed., Homeri Opera V (Oxford 1946) 105f, esp. 106.12-15. On the identity of the AEVKT, ~(J'o<; with Elysium and the Isles of the Blessed see E. -

Lecture 23 Okay on Monday You Talked About What It Takes to Make a Hero, Versus Hughes’S Herometer

Lecture 23 Okay on Monday you talked about what it takes to make a hero, versus Hughes’s Herometer. How did that go? Do you have a pretty good idea of what a hero is in general? Or did he talk specifically about a Greek hero? Just in general. So you know some things that are going to happen in the Heracles myth, even before we start, right? Okay, we’ll start with his name, which means what? Ankle? No, you’re thinking maybe of Oedipus on that one. The material I am lecturing to you is taken from pages 420-448 in your book. We’ll go through the material as it’s presented, basically, through the book if you want to take a look there. His name means something to do with Hera. Pain of Hera? Close. It is the glory of Hera, believe it or not. So the person or the divinity that gives him the most trouble in his life and causes him to do some very horrible things, turns out to be his patron, of sorts. What he does glorifies her, according to the name, anyhow. Now, when you have a hero, they don’t just spring from anywhere or nowhere. They generally have something in their background to indicate they’re going to do something glorious. So let’s take a look at Heracles’ heritage. Where does he ultimately come from? Who is in his background that’s illustrious? Yeah, Zeus himself is the father. If you look at the chart on Heracles’ heritage you’ll be able to see this a bit better. -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Artistic Interpretation of Amphitryon Story in Dramas by J. Giraudoux and P

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 5 (2016 9) 1067-1073 ~ ~ ~ УДК 82-2 Artistic Interpretation of Amphitryon Story in Dramas By J. Giraudoux and P. Hacks Tatiana S. Nipa* and Vladislav E. Biktimirov Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 12.01.2016, received in revised form 24.02.2016, accepted 15.03.2016 The present article studies the peculiarities of artistic perception of the classical story of Amphitryon in plays by J. Giraudoux and P. Hacks. The myth of this Theban commander has been interpreted plenty of times (by Plautus, Molière, Dryden, Kleist, Giraudoux, Kaiser, Hacks) during the development of foreign literature. In different epochs, this motif attracted authors with more than just dynamic intrigue and the comic twins situation, but also with the opportunities it provides to raise some general philosophic and ontological issues. In the 20th century remarkable for the intensive technical development and powerful social and political cataclysms, the writers of the new generation turned to the old story again. The comparative analysis of dramas by Giraudoux and Hacks is a way to reveal similarities and differences in the perception of the mythological material explained both by the time when the dramas were written and by the peculiarities of the world outlook and aesthetical principles of the given authors. Keywords: J. Giraudoux, P. Hacks, Amphitryon, perception, myth, interpretation. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-5-1067-1073. Research area: philology. Introduction guise of her husband Amphitryon, who was away Classical mythology takes an exceptional at war, Zeus made love to her.