HERACLES Tratlslated by William Arrowsmith • HERA C I.Ils ~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odyssey Glossary of Names

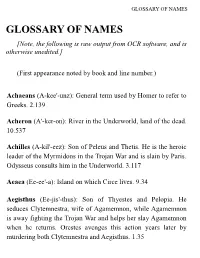

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

The Death of Eurydice Orpheus' Descent Into Hades

Myth #4 Orpheus and Eurydice Name _____________________________________ READ CLOSELY AND SHOW EVIDENCE OF THINKING BY ANNOTATING. Annotate all readings by highlighting the main idea in yellow; the best evidence supporting in blue, and any interesting phrases in green. As it is only fitting, Orpheus, “the father of songs” and the supreme musician in Greek mythology, was the son of one of the Muses, generally said to be Calliope, by either Apollo or the Thracian king Oeagrus. Be that as it may, we know for sure that Orpheus got a golden lyre as a gift from Apollo when just a child, and that it was the god who taught him how to play it in such a beautiful manner. Moreover, his mother showed him how to add verses to the music, and his eight aunts how to polish them to perfection, in every style known to man. So, when Orpheus was a young man, as Shakespeare writes, his “golden touch could soften steel and stones, make tigers tame, and huge leviathans forsake unsounded deeps to dance on sands.” Loved by many, this young man loved only the beautiful Eurydice; and she loved him back. This is the story of their tragic love. The Death of Eurydice Soon after the marriage of Orpheus and Eurydice, Eurydice died of a snake bite. Different authors tell different stories as to what led to the fatal encounter. According to the most repeated story, Eurydice fell into a serpent nest after trying to escape from a certain Aristaeus, a shepherd who began to chase her through the forest as soon as he laid his eyes upon her otherworldly beauty. -

Excerpt from Euripides' Herakles

Excerpt from Euripides’ Herakles (lines 1189-1426) The action up until now: The goddess Hera has sent Madness upon Herakles. Madness has driven Herakles to kill his wife and his children. He mistook them for his enemies, being under the influence of Madness. Herakles is just coming out of the frenzied state he was in, and beginning to realise what he has done. He is contemplating suicide. Suddenly, Theseus of Athens appears on the scene. After a discussion with Herakles’ father Amphitryon, Theseus learns what has happened. At this moment, Herakles is lying in among his dead family members, ashamed of his actions, not wanting Theseus to see his face. I have included some lines here of the discussion between Theseus and Amphitryon, that will lead into the essential discussion between Herakles and Theseus. Theseus What do you mean? What has he done? Amphitryon Slain them in a wild fit of frenzy with arrows dipped in the venom of the hundred-headed hydra. Theseus This is Hera's work; but who lies there among the dead, old man? Amphitryon My son, my own enduring son, that marched with gods to Phlegra's plain, there to battle with giants and slay them, warrior that he was. Theseus Ah, ah! whose fortune was ever so cursed as his? Amphitryon Never will you find another mortal that has suffered more or been driven harder. Theseus Why does he veil his head, poor wretch, in his robe? Amphitryon He is ashamed to meet your eye; his kinsman's kind intent and his children's blood make him abashed. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

General Index

GENERAL INDEX A.GILIM, and n. Aesopic tradition, , and abstractions, n. nn. –, Acarnania, Aetna, , Acastus, Aetna, n. Accius, and n. Agamemnon, n. , , , accusative, , n. , –, , –, , – Agdistis, Achelous, Agenor, Achilles, , , , , , , , ages, myth of, see races, myth of –, , , , , Agias of Troezen, , Acontius, , n. , , agriculture, , , , , , – and n. , , , , , –, Actaeon, n. , , , , n. , –, ; Actor, agriculture section in Works and Acusilaus of Argos, and n. , Days, , , –, and n. Agrius, Adad, aidos, n. , ; personified, , adamant, adjective(s), , , Aietes, Admonitions of Ipuwar,andn. Aigipan, Adodos, ainos, , –, Adrasteia, Aither, and n. Adriatic (sea), Aithon, , n. Aegean (sea), , , aitiology, , , nn. –, Aegimius, – and n. , , , and Aegle, , n. , , , , Aelian Ajax son of Oileus, Historical miscellany, , Ajax son of Telamon, , , – and n. Aeolic dialect, , –, , Akkadian, n. , n. , , , , –; East Al Mina, , or Asiatic Aeolic, –, Alalu, , n. , , Alcaeus, , , n. Aeolids, , , Alcidamas, , , , , , Aeolis, Eastern, , , –, , n. Aeolism, , , , Alcinous, , n. , n. , Aeolus, –, , , , Aeschines, Alcmaeonidae, Aeschylus, , , , and Alcmaeonis, n. , Alcman, n. , and n. , Prometheus Bound, n. , and n. n. Alcmaon, – general index Alcmene, –, –, Antoninus Liberalis, , , n. , , , Anu, –, , –, –, aoidos see singer Alcyone, , , , aorist, , –, Alexander Aetolus, , n. apate, ; personified, Alexander the Great, n. , Aphrodite, , , n. , and n. , n. , and n. , -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

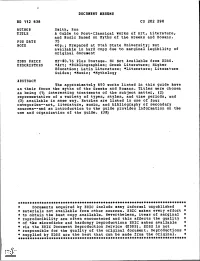

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Worksheet 4. Orpheus and Eurydice (Teacher)

Ovid’s Metamorphoses: A Common Core Exemplar Worksheet 4. Orpheus and Eurydice (teacher) Comparing two versions of the Orpheus and Eurydice story (teacher version) Directions: Use the space below to identify the main similarities of the Orpheus and Eurydice story in the accounts by Ovid and H.D. The basic plot is the same: Orpheus has gone down to the underworld to rescue his wife Eurydice. Because he looks back as they are climbing up, contrary to the mandate of the god, she must return. Now list their differences, using the criteria in the chart below. Under the column headed “So What?” explain why each difference is significant. Additional cells have been included to allow students room to add their own criteria. Ovid’s “Orpheus and Criterion Eurydice” H.D.’s “Eurydice” So What? Begins with the wedding Begins with Eurydice’s Ovid tells the full story Opening of the poem and failure of Hymen to bitter anger at Orpheus from beginning to end. bless it for his arrogance Hymen’s appearance and actions are a foreshadowing of what will happen. H.D. is more focused, telling only a few minutes of the story. Ovid is the omniscient Eurydice speaks in first Ovid is classical, Narrator narrator, telling the story person, clearly expressing relatively restrained in in a measured, her anger and frustration emotion, even in a tale unemotional tone. and using elaborate, involving the underworld, heartfelt descriptions. death, and lost love. H.D. exhibits more of a modern, romantic tone, bursting with resentment and feeling. Orpheus is loving and Orpheus’s personality is Good example of how Attitude of Eurydice brave; he even declares only conveyed through point of view can radically his willingness to die Eurydice’s eyes, and she alter the interpretation of himself if he can’t have views him as “arrogant” a narrative. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too.