AFGHANISTAN? a Study of Afghans Living in Tehran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

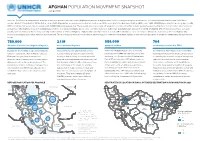

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF UNIVERSITY OF TURKU MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations Patterns Migration in Iran: Afghans No. 14 TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TURKU No. 1. Jukka Käyhkö and Tim Horstkotte (Eds.): Reindeer husbandry under global change in the tundra region of Northern Fennoscandia. 2017. No. 2. Jukka Käyhkö och Tim Horstkotte (Red.): Den globala förändringens inverkan på rennäringen på norra Fennoskandiens tundra. 2017. No. 3. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (doaimm.): Boazodoallu globála rievdadusaid siste Davvi-Fennoskandia duottarguovlluin. 2017. AFGHANS IN IRAN: No. 4. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (Toim.): Globaalimuutoksen vaikutus porotalouteen Pohjois-Fennoskandian tundra-alueilla. 2017. MIGRATION PATTERNS No. 5. Jussi S. Jauhiainen (Toim.): Turvapaikka Suomesta? Vuoden 2015 turvapaikanhakijat ja turvapaikkaprosessit Suomessa. 2017. AND ASPIRATIONS No. 6. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers in Lesvos, Greece, 2016-2017. 2017 No. 7. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. 2017 Nro 172 No. 8. Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Katri Gadd & Justus Jokela: Paperittomat Suomessa 2017. 2018. Salavati Sarcheshmeh & Bahram Eyvazlu Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Davood No. 9. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Davood Eyvazlu: Urbanization, Refugees and Irregular Migrants in Iran, 2017. 2018. No. 10. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Ekaterina Vorobeva: Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan, 2017. 2018. (Eds.) No. 11. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey, 2018. 2018. TURKU 2008 ΕήΟΎϬϣΕϼϳΎϤΗϭΎϫϮ̴ϟϥήϳέΩ̶ϧΎΘδϧΎϐϓϥήΟΎϬϣ ISBN No. -

Urban Poverty in Vietnam – a View from Complementary Assessments

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT HUMAN SETTLEMENTS WORKING PAPER SERIES POVERTY REDUCTION IN URBAN AREAS – 40 Urban pov erty in V iet nam – a vi ew from com plementary asses sments by HOANG XUAN THANH, with TRUONG TUAN ANH and DINH THI THU PHUONG OCTOBER 2013 HUMAN SETTLEMENTS GROUP Urban poverty in Vietnam – a view from complementary assessments Hoang Xuan Thanh, with Truong Tuan Anh and Dinh Thi Thu Phuong October 2013 i ABOUT THE AUTHORS Hoang Xuan Thanh, Senior Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Truong Tuan Anh, Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Dinh Thi Thu Phuong, Researcher, Ageless Consultants, Vietnam [email protected] Acknowledgements: This working paper has been funded entirely by UK aid from the UK Government. Its conclusions do not necessarily reflect the views of the UK Government. © IIED 2013 Human Settlements Group International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8NH, UK Tel: 44 20 3463 7399 Fax: 44 20 3514 9055 ISBN: 978-1-84369-959-0 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from http://pubs.iied.org/10633IIED.html Disclaimer: The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed here do not represent the views of any organisations that have provided institutional, organisational or financial support for the preparation of this paper. ii Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................................. -

REFUGEES Rn Lran* by Il Hobin Shorish University of Illinois At

Bismiallah THE AFGHAt! REFUGEES rn lRAN* by i.l. Hobin Shorish University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Throughout the recent histories of Iran and Afghanistan refugees of one form or another have existed in each of these lands. Political and religious refugees have almost always constituted the majority of those who sought either Afghanistan or Iran as their new haven. The most recent Iranian wave of refugees in the Khurasan area of Afghanistan (Herat) has been those who feared the develop-· ment of conflict in Iran between the super powers during the Second World War. Since, fortunately, such a conflict did not develop some of the Iranians who fled to Herat and other western provinces of Afghanistan returned to Iran and others '"'ettled in these areas, especially in Herat, to become citizens of the Afghan kin~dom. In all fonns of human transmigration it is the magnitude of the people moving that create problems often for the host countries. Therefore:, an in vestigation into the problems of the Afghan refugees in Iran, and the Iranians' attidude toward these refugees was needed for the benefit of those concerned uith the tragedy of Afghanistan and the brutality befalling the Afghan people by the Russians and their puppets in Kabul. The Afghan Refugees--~heir Number and Origins: Today, in Iran the magnitude of the Afghan refugees is unknmm. The refugees themselves are vague in their ansuers to the questions eliciting the number. They often articulate their answer in the following manner: "There are manyn~ "There are a lot of them";: "Afghans are scattered from Tabriz to Tayabad"; ''We are everywhere". -

Iran's Sunnis Resist Extremism, but for How Long?

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Iran’s Sunnis Resist Extremism, but for How Long? APRIL 2018 SCHEHEREZADE FARAMARZI ome fifteen million of Iran’s eighty million people are Sunni Muslims, the country’s largest religious minority. Politically and economically disadvantaged, these Sunnis receive relatively lit- tle attention compared with other minorities and are concen- Strated in border areas from Baluchistan in the southeast, to Kurdistan in the northwest, to the Persian Gulf in the south. The flare up of tensions between regional rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran over Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen would seem to encourage interest in the state of Iranian Sunnis, if only because the Saudis present them- selves as defenders of the world’s Sunnis, and Iran the self-appointed champion of the Shia cause. So how do Iran’s Sunnis fare in a state where Shia theology governs al- most every aspect of life? How have they been affected by this regional rivalry? Are they stuck between jihadist and other extreme regional Sunni movements on the one hand, and the Shia regime’s aggres- sive policies on the other? Is there a danger that these policies could push some disgruntled Iranian Sunnis toward militancy and terrorism? A tour of Turkmen Sahra in the northeast of Iran near the Caspian Sea, and in Hormozgan on the Persian Gulf in 2015 and 2016 revealed some of the answers. More recent interviews were conducted by phone and in person in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and with European-based experts. “Being a Sunni in Iran means pain, fear, anxiety, restrictions,”1 said a young The Atlantic Council’s South woman in a southern Hormozgan village. -

Afghanistan: Compilation of Country of Origin Information (COI)

Afghanistan: Compilation of Country of Origin Information (COI) Relevant for Assessing the Availability of an Internal Flight, Relocation or Protection Alternative (IFA/IRA/IPA) to Kabul December 2019 This document provides decision-makers with relevant country of origin information (COI) for assessing the availability of an internal flight, relocation or protection alternative (IFA/IRA/IPA) in Kabul for Afghans who originate from elsewhere in Afghanistan and who have been found to have a well-founded fear of persecution in relation to their home area, or who would face a real risk of serious harm in their home area. UNHCR recalls its position that given the current security, human rights and humanitarian situation in Kabul, an IFA/IRA is generally not available in the city. See: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Asylum-Seekers from Afghanistan, 30 August 2018, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5b8900109.html, p. 114. Table of Contents 1. The relevance of Kabul as an IFA/IRA: the security situation for civilians in Kabul ............. 2 1.1 Security Trends and Impact on Civilian Population in 2019 ................................................. 2 1.2 Presence and Activity of the Taliban in Kabul....................................................................... 6 1.3 Presence and Activity of ISIL in Kabul .................................................................................. 6 1.4 Other Security Threats in Kabul ........................................................................................... -

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? the Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900

Popular, Elite and Mass Culture? The Spanish Zarzuela in Buenos Aires, 1890-1900 Kristen McCleary University of California, Los Angeles ecent works by historians of Latin American popular culture have focused on attempts by the elite classes to control, educate, or sophisticate the popular classes by defining their leisure time activities. Many of these studies take an "event-driven" approach to studying culture and tend to focus on public celebrations and rituals, such as festivals and parades, sporting events, and even funerals. A second trend has been for scholars to mine the rich cache of urban regulations during both the colonial and national eras in an attempt to mea- sure elite attitudes towards popular class activities. For example, Juan Pedro Viqueira Alban in Propriety and Permissiveness in Bourbon Mexico eloquently shows how the rules enacted from above tell more about the attitudes and beliefs of the elites than they do about those they would attempt to regulate. A third approach has been to examine the construction of national identity. Here scholarship explores the evolution of cultural practices, like the tango and samba, that developed in the popular sectors of society and eventually became co-opted and "sanitized" by the elites, who then claimed these activities as symbols of national identity.' The defining characteristic of recent popular culture studies is that they focus on popular culture as arising in opposition to elite culture and do not consider areas where elite and popular culture overlap. This approach is clearly relevant to his- torical studies that focus on those Latin American countries where a small group of elites rule over large predominantly rural and indigenous populations. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

The NFDA Cremation and Burial Report: Research, Statistics and Projections September 2014

The NFDA Cremation and Burial Report: Research, Statistics and Projections September 2014 A brand-new state-of-cremation publication featuring statistical information and in-depth analysis of the state of cremation today and what it means for you. The NFDA 2014 Cremation Report: Research, cost-effective for consumers. It is often followed by some Statistics and Projections type of memorialization event with family and friends – but frequently without the services of a funeral home. This results NFDA is the leading and largest funeral director in increased competition from the direct cremation (direct disposal)general sector. more cost-effective for consumers. It is often Theassociation NFDA in the 2014 world. Cremation We help our members Report: achieve followed by some type of memorialization event with Research,more by providing Statistics tools to manage, and a Projections successful family and friends – but frequently without the services of business. Thea funeralrising popularity home. This of cremation results in isincreased attributable competition to a number from NFDA is the leading and largest funeral director association of thfactors,e direct including cremation cost, (direct decreased disposal) household sector. discretionary in the world. We help our members achieve more by State of the Funeral Service Industry income, rising funeral expenses that continue to outpace providing tools to manage a successful business. inflationThe rising (Batesville, popularity 2013), of cremation environmental is attributable concerns, tofewer -

A Regional View of Wheat Markets and Food Security In

A REGIONAL VIEW OF WHEAT MARKETS AND FOOD SECURITY IN CENTRAL ASIA WITH A FOCUS ON AFGHANISTAN AND TAJIKISTAN JULY 2011 This publication was authored by Philippe Chabot and Fabien Tondel under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), indefinite quantity contract no. AFP -I-00-05-00027-00, managed by Chemonics International Inc. A REGIONAL VIEW OF WHEAT MARKETS AND FOOD SECURITY IN CENTRAL ASIA WITH A FOCUS ON AFGHANISTAN AND TAJIKISTAN The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development, the United States government, or the World Food Programme. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... ix I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Socioeconomic and Food-Security Contexts ............................................................................................ 3 III. Trends in Wheat Production and Trade ................................................................................................... 7 IV. Geography of Wheat Production and Trade ........................................................................................ -

IRAN INFECTION MEASURES CONTROL PROVIDING GUIDANCE RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT RISKS ABOUT AWARENESS RAISING Dead

IRAN THE ICRC’S COVID-19 RESPONSE MARCH-AUGUST 2020 FACTS AND FIGURES FACTS INFECTION CONTROL MEASURES The ICRC has worked to address the immediate needs of vulnerable people at risk of being infected by COVID-19. Joint activities carried out by the ICRC, the Iranian Red Crescent Society and Pars Development Activists include the following: We have provided information on COVID-19 infection control to vulnerable migrants in Zahedan and Iranshahr, in the province of Sistan and Baluchestan. We have provided 1,780 hygiene kits to 200 migrant families in Zahedan and to 85 families in Iranshahr. RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT RISKS The ICRC and the Iranian Red Crescent Society work together to raise awareness about weapon contamination and mine risks among Iranians and Afghans living in Iran: We have provided nomads in the province of Kermanshah, western Iran, with information on mine risks during Red Crescent activities on COVID-19 prevention. Red Crescent focal points shared information about mine risks on local social media channels, with an estimated 2,000 people reached in the provinces of Kurdistan and Kermanshah in March and April 2020. We plan to integrate information about COVID-19 with messages about mine risks for Iranians living in contaminated areas. In addition, the Iranian government and the Iranian Red Crescent Society have approved a range of activities to support Afghan returnees. About 1,000 people a day are returning to their home country. Returnees at the Iran–Afghanistan border will receive hygiene items and information about mine risks, COVID-19 and family links services. These activities have already started. -

The Bush Revolution: the Remaking of America's Foreign Policy

The Bush Revolution: The Remaking of America’s Foreign Policy Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay The Brookings Institution April 2003 George W. Bush campaigned for the presidency on the promise of a “humble” foreign policy that would avoid his predecessor’s mistake in “overcommitting our military around the world.”1 During his first seven months as president he focused his attention primarily on domestic affairs. That all changed over the succeeding twenty months. The United States waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S. troops went to Georgia, the Philippines, and Yemen to help those governments defeat terrorist groups operating on their soil. Rather than cheering American humility, people and governments around the world denounced American arrogance. Critics complained that the motto of the United States had become oderint dum metuant—Let them hate as long as they fear. September 11 explains why foreign policy became the consuming passion of Bush’s presidency. Once commercial jetliners plowed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is unimaginable that foreign policy wouldn’t have become the overriding priority of any American president. Still, the terrorist attacks by themselves don’t explain why Bush chose to respond as he did. Few Americans and even fewer foreigners thought in the fall of 2001 that attacks organized by Islamic extremists seeking to restore the caliphate would culminate in a war to overthrow the secular tyrant Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Yet the path from the smoking ruins in New York City and Northern Virginia to the battle of Baghdad was not the case of a White House cynically manipulating a historic catastrophe to carry out a pre-planned agenda.