The Unity of Biblical Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ford-Judgment in 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham FINAL

Abstract Judgment in 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham By: Jason Ford When the Roman army destroyed Jerusalem’s temple in 70 CE, it altered Jewish imagination and compelled religious and community leaders to devise messages of consolation. These messages needed to address both the contemporary situation and maintain continuity with Israel’s religious history. 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch, and Apocalypse of Abraham are three important witnesses to these new messages hope in the face of devastation. In this dissertation I focus on how these three authors used and explored the important religious theme of judgment. Regarding 4 Ezra, I argue that by focusing our reading on judgment and its role in the text’s message we uncover 4 Ezra’s essential meaning. 4 Ezra’s main character misunderstands the implications of the destroyed Temple and, despite rounds of dialogue with and angelic interlocutor, he only comes to see God’s justice for Israel in light of the end-time judgment God shows him in two visions. Woven deeply into the fabric of his story, the author of 2 Baruch utilizes judgment for different purposes. With the community’s stability and guidance in question, 2 Baruch promises the coming of God’s judgment on the wicked nations, as well as the heavenly reward for Israel itself. In that way, judgment serves a pedagogical purpose in 2 Baruch–to stabilize and inspire the community through its teaching. Of the three texts, Apocalypse of Abraham explores the meaning of judgment must directly. It also offers the most radical portrayal of judgment. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 4 Number 1 Article 52 1992 The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Michael D. Rhodes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Rhodes, Michael D. (1992) "The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 52. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol4/iss1/52 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Author(s) Michael D. Rhodes Reference Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 4/1 (1992): 120–26. ISSN 1050-7930 (print), 2168-3719 (online) Abstract Review of . By His Own Hand upon Papyrus: A New Look at the Joseph Smith Papyri (1992), by Charles M. Larson. Charles M. Larson, ••. By His Own Hand upon Papyrus: A New Look at the Joseph Smith Papyri. Grand Rapids: Institute for Religious Research, 1992. 240 pp., illustrated. $11.95. The Book of Abraham: Divinely Inspired Scripture Reviewed by Michael D. Rhodes The book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price periodically comes under criticism by non-Monnons as a prime example of Joseph Smith's inability to translate ancient documents. The argument runs as follows: (1) We now have the papyri which Joseph Smith used to translate the book of Abraham (these are three of the papyri discovered in 1967 in the Metropolitan Museum of An in New York and subsequently turned over to the Church; the papyri in question are Joseph Smith Papyri I. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of Saint John and the Sefer Zerubbabel

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Theology & Religious Studies College of Arts and Sciences 12-30-2016 On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of Saint John and the Sefer Zerubbabel Natalie Latteri Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thrs Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel Natalie E. Latteri, University of New Mexico, NM, USA Abstract The Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel [a.k.a Apocalypse of Zerubbabel] are among the most popular apocalypses of the Common Era. While the Johannine Apocalypse was written by a first-century Jewish-Christian author and would later be refracted through a decidedly Christian lens, and the Sefer Zerubbabel was probably composed by a seventh-century Jewish author for a predominantly Jewish audience, the two share much in the way of plot, narrative motifs, and archetypal characters. An examination of these commonalities and, in particular, how they intersect with gender and sexuality, suggests that these texts also may have functioned similarly as a call to reform within the generations that originally received them and, perhaps, among later medieval generations in which the texts remained important. The Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel, or Book of Zerubbabel, are among the most popular apocalypses of the Common Era.1 While the Johannine Apocalypse was written by a first-century Jewish-Christian author and would later be refracted through a decidedly Christian lens, and the Sefer Zerubbabel was probably composed by a seventh-century Jewish author for a predominantly Jewish audience, the two share much in the way of plot, narrative motifs, and archetypal characters. -

Radionytt Musik 15 Januari 2020

Radionytt Musik 15 januari 2020 ● ADDERING ★ VECKANS SINGEL/HITVARNING AL ALBUM Radionytt Musik publiceras på onsdagar av Radionytt. E AVANTGARDET CUL DE SAC C MICHAELA ANNE BY OUR DESIGN E C BELLA BOO YOUR GIRLFRIEND C MIRANDA LAMBERT IT AL COMES OUT IN SVERIGES RADIO E DREE LOW DAG HAMMARSKJÖLD C ● MOLLY SANDÉN ALLA VÅRA SMEKNAMN E D FKA TWIGS SAD DAYS C B MÅNS ZELMERLÖW BETTER NOW E FLUME RUSHING BACK C ORUP VAKUUM E FREJA THE DRAGON GIVE IT ALL UP C ● OZZY OSBOURNE ORDINARY MAN E HIGHASAKITE CAN I BE FORGIVEN C PAUL MCCARTNEY HOME TONIGHT P3 Esau Alcona, Linda Nordeman, Mari Hesthammer E D KALI UCHIS SOLITA C SARA ZACHARIAS HJÄRTSLAG A B AVICII FADES AWAY E C KASBO I GET YOU C ULF LUNDELL STOCKHOLM I OKTOBER A BILLIE EILISH EVERYTHING I WANTED E MADEON MIRACLE C VERONICA MAGGIO FIENDER ÄR TRÅKIGT A DREE LOW PIPPI E REIN OFF THE GRID D ● ASHLEY MCBRYDE ONE NIGHT STANDARDS A DUA LIPA DON’T START NOW E ROLE MODEL SAY IT FIRST D ● AVA MAX SALT A D HARRY STYLES ADORE YOU E ● STRØM LAST TRY D BO KASPERS ORKESTER DEN SISTA RESAN A ● JUSTIN BIEBER YUMMY E 1975 FRAIL STATE OF MIND D CAJSA-STINA ÅKERSTRÖM VINTERÄPPLEN A B PARTYNEXTDOOR LOYAL E TARANTULA WALTZ FALLIN’ D CASANOVAS IKVÄLL ÄR DET JAG SOM ÄR A D STORMZY OWN IT E C YUNG LEAN BLUE PLASTIC D DYLAN LEBLANC BORN AGAIN A TAYLOR SWIFT LOVER (RMX) D ELLEN KRAUSS THE ONE I LOVE A B WEEKND BLINDING LIGHTS D HARRY STYLES LIGHTS UP A ● WINONA OAK CONTROL D ● JAMES BLUNT THE TRUTH A WINONA OAK LET ME KNOW D B JOSÉ GONZÁLEZ WATERFALLS B ● ALAN WALKER ALON,E PT 2 D ● LEWIS CAPALDI BEFORE YOU GO -

Getting the Big Picture of the Bible Pastor Michael Wallace September 9, 2018 Westminster Hall Sunday School Class

Getting the Big Picture of the Bible Pastor Michael Wallace September 9, 2018 Westminster Hall Sunday School Class Selection from the Codex Sinaticus, which does not contain the pericope de adultera, commonly found now in John 7:53—8:11 How should we understand the printed Bible? • Do we have just one book? • Is it more like a library or a compendium? • Who wrote the books of the Bible? (Authorship) • Written by dozens of different authors • When did they write? (Dating) • The books of the Bible were written over more than a 1,000 year time span (c. 1000 BC-100 AD) • Where did they write? (Location and condition) • In the wilderness • In times of plenty and political/ cultural flourishing • In exile/ captivity/ prison • To whom did they write? (Audience) • The children of Israel (who were familialy bound to the covenant) • To Jews who believed in Jesus or to Gentiles to believed in Jesus • In what language did the authors write the Bible? שבעים פנים לתורה Shiv'im Panim l'Torah The Torah has 70 Faces • This phrase is sometimes used to indicate different "levels" of interpretation of the Torah. • "There are seventy faces to the Torah: Turn it around and around, for everything is in it" (Bamidbar Rabba 13:15). • Like a gem, we can examine it from different angles. • Even by holding it up to different lights, we can see it differently. If you asked me, “Where do you live?,” how helpful would it be if… Many different approaches & questions: Going from the MACRO to the MICRO All (Religious) Literature from the Ancient Near East All (Religious) Literature contemporaneous with Hebrew Bible & New Testament Scripture (Apoc & Pseud) Literature considered canonical/ authoritative by Protestants today Genres/ Themes/ Eras Individual Books Narrative Arcs Phrases Words Religious Literature from the Ancient Near East Comparing Genesis with the Enûma Eliš • A Babylonian creation story where the god Marduk kills his nemesis Tiamat and then fillets her body in two, making the sky out of one half and the earth out of the other. -

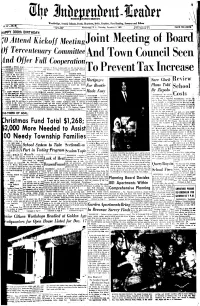

1 O Rrevent 1 Ax Increase

EDISON J FORDS BtACON V, Woodbridge, Avenel, Colonia, Fords, Hopelawn, Iselin, Keasbcy, Port Reading, Sewaren and Edison Vol. LV - SO. SI Puhll«h«d Weekly Woodbridge, N. J., Thursday, December 5, 1963 ftntcred H Jnd Clwui Mill PRICE TEN GENTS On ThurndBj At P.O., Woodbrldgft, H. J. HAPPY 300th BIRTHDAY: 70 Attend Kickoff MeetingJoint Meeting of Board •/ Tercentenary Committee And Town Council Seen And Offer Fidl Cooperation™ n . m T WOODBRIDGE r- Seventy in- gr;nns to Tw--consisting of Manny Goldfarb.|4S0O, ext, 277, who has been as- jed townspeople attended the ran in, John Pctrossi and Arthur Fried- signed to assist with Tercenten- i general meeting of the Wood- H r -. MII^I'MHI Hint dubs and man, ary work. •jilee Tercentenary Committee 1 o rrevent 1 ax Increase itinns mipht want to sell] Chairmen to Get List Committee* Named y night it the homo of Ter i -njiry items, many of! Copies of the calendar of events The Committees are as follows: and Mn. Walter Zirpolo, ;)n. available from arealand the schedule of committees Executive Committee: Miss iionin. and enthuxlastlcally of firm including tiles, dishes, will be sent to all sub-committee Wolk, general chairman; Mayor I to serve on the various mib- r.wly iiiul hultiins. Koy chairmen who are to schedule Zirpolo. Roy Doctofsky, Patrick Mortgages Save Clock Review bninntlees for the many event* dipfsky. with the assistance of meetings with .he executive com- A. Boylan, S. Buddy Harris, He- nncd during the coming year the Mercury Federal Savings mittee to work out details of the man B. -

TITEL ARTIST LÄNGD År/ANM Come Take My Hand 2 Brothers on The

TITEL ARTIST LÄNGD År/ANM Come Take My Hand 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor 00:03:17 1995 Do What's Good For Me 2 Unlimited 00:03:50 1995 Shimmy Shake (Radio Mix) 740 Boyz 00:03:35 1995 La Dolce Vita (Sound Factory 2018 Mix) After Dark 00:03:25 2018 Let's Go Party After Dark (SoundFactory Radio Mix) After Dark 00:03:50 2018 Min Bästa Vän After Dark 00:03:23 2018 Nå't På Gång After Dark 00:04:03 2018 Party After Dark After Dark 00:03:26 2018 The Big Spenders Suite (Radio Edit) After Dark 00:03:22 2018 Älska Mig After Dark 00:03:53 2018 Love Love Love Agnes 00:03:00 2009 Banjo Picking Man Agö Fyr 00:02:21 1977 Because You Come To Me Al Tornello 00:02:20 2021 Black Is The Color Of My True Love's Hair Al Tornello 00:02:51 2021 None But The Lonely Heart Al Tornello 00:02:01 2021 Oh Marie Al Tornello 00:01:48 2021 On The Road To Mandalay Al Tornello 00:02:39 2021 When You Were Sweet Sixteen Al Tornello 00:02:50 2021 Tampico Alberto Ruiz And His Orchestra 00:02:29 1968 Stay The Night Alcazar 00:03:01 2009 Wrap Me Up Alex Party 00:03:45 1995 Wrap Me Up (Radio Edit) Alex Party 00:03:45 1995 Balladen Om Ole Høiland Alf Cranner 00:01:52 1970 Blåklokkeleiken Alf Prøysen 00:02:56 1955 Fjellsangen Alfred Maurstad 00:02:50 1939 Bailá Bailá Alvaro Estrella 00:02:56 2021 La Rumba Alvaro Gomez-Orozco And His Orchestra 00:04:42 1986 Los Morenos Ambros Seelos And His Orchestra 00:03:18 1989 Memory Ambros Seelos And His Orchestra 00:03:14 1986 Yours (Quiereme Mucho) Ambros Seelos And His Orchestra 00:02:44 1985 Mambo Fever Ambrose & His Orchestra 00:02:34 1989 It's My Life Amy Diamond 00:03:05 2009 Askan Är Den Bästa Jorden Ana Diaz 00:02:34 2020 Fait Accompli Ana Diaz 00:03:01 2020 Regnet Ana Diaz 00:03:30 2020 Vara Vänner Ana Diaz 00:03:21 2020 Vår Lilla Stad Ana Diaz 00:03:16 2020 3 Chorales for Organ: No. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

Tidningen Contakt Februari 2021

Nummer 1 Februari 2021 CONTAKT Årgång 20 Vård och omsorg, Daglig Verksamhet Carma 24 1 Redaktionssidan Vinnare i tävlingen i Detta kan du vinna: nummer 6/2020 blev I DETTA NUMMER: Den som vinner får välja Omslag: en tygväska Sidan 3: Diego Maradona Elina på Carma Annika Öhrn eller Sidan 4: Teorier, tankar och funderingar två fruktpåsar Sidan 5: Vi Fem-fråga Grattis! Vill du ha med något i tidningen? Sidan 6, 7 & 8: Sägner, myter & legender Ring eller skicka det via post Sidan 9: Teorier av tankar & funderingar eller email: Som vi syr på Carma. Tidningen Contakt Sidan 10 & 11: Recept: Saffranssemlor med Skriv svaret, ditt namn och arbetsplats eller hemadress och skicka den till: Carma hallongrädde Pilgatan 8A Carma 721 30 Västerås Sidan 12 & 13: Bildrecept: Våfflor Pilgatan 8A [email protected] Sidan 14 & 15: Recept: Klassiska Semlor 721 87 Västerås Tryckt av Carma Sidan 16: Martinez 40 år! 021-39 32 45, 021-39 41 49, [email protected] Sidan 17: Melodifestivalen 2021 021-39 84 54 Senast onsdagen den 21 april. Sidan 18 : Knep & Knåp och roliga Skriv TÄVLING på kuvertet eller i mejlet. historier Vill du prenumerera på Contakt? Sidan 19 & 20 : Sven Wollter Ringa in vad du vill ha om du Tävling vinner: Sidan 21 : Margreth Weivers Kontakta Carma på nummer: 021-39 32 45, 021-39 41 49, Sidan 22 : Vårbild & artiklar sökes! Var kreativ! Vinn ett omslag Tygväska: 021-39 84 54 Sidan 23 & 24 : Sista sidan & tävling! till nästa tidning! En prenumeration kostar: Fruktpåsar: 100 kronor. Ett lösnummer kostar: Skicka in en bild som du 20 kronor. -

Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies

0 Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies Bibliography largely taken from Dr. James R. Davila's annotated bibliographies: http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~www_sd/otpseud.html. I have changed formatting, added the section on 'Online works,' have added a sizable amount to the secondary literature references in most of the categories, and added the Table of Contents. - Lee Table of Contents Online Works……………………………………………………………………………………………...02 General Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...…03 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………....03 Translations of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in Collections…………………………………….…03 Guide Series…………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 On the Literature of the 2nd Temple Period…………………………………………………………..........04 Literary Approaches and Ancient Exegesis…………………………………………………………..…...05 On Greek Translations of Semitic Originals……………………………………………………………....05 On Judaism and Hellenism in the Second Temple Period…………………………………………..…….06 The Book of 1 Enoch and Related Material…………………………………………………………….....07 The Book of Giants…………………………………………………………………………………..……09 The Book of the Watchers…………………………………………………………………………......….11 The Animal Apocalypse…………………………………………………………………………...………13 The Epistle of Enoch (Including the Apocalypse of Weeks)………………………………………..…….14 2 Enoch…………………………………………………………………………………………..………..15 5-6 Ezra (= 2 Esdras 1-2, 15-16, respectively)……………………………………………………..……..17 The Treatise of Shem………………………………………………………………………………..…….18 The Similitudes of Enoch (1 Enoch 37-71)…………………………………………………………..…...18 The