The Fantasy Quest and the Heroine's Journey Bronwyn Calder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

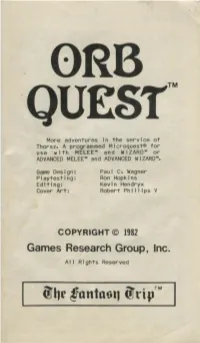

ORB QUEST™ Is a Programmed Adventure for the Instruction, It W I 11 Give You Information and FANTASY TRIP™ Game System

0RB QUEST™ More adventures in the service of Thorsz. A programmed Microquest® for use with ME LEE'" and WIZARD'" or ADVANCED MELEE'" and ADVANCED WIZARD'". Game Design: Paul c. Wagner Playtesting: Ron Hopkins Editing: Kevin Hendryx Cover Art: Robert Phillips V COPYRIGHT© 1982 Games Research Group, Inc. Al I Rights Reserved 3 2 from agai~ Enough prospered, however, to establish INTRODUCTION the base of the kingdom and dynasty of the Thorsz as it now stands. During evening rounds outside the w i. zard's "With time and the excess of luxuries brought quarters at the Thorsz's pa I ace, you are. deta 1 n~~ b~ about by these successes, the fate of the ear I i er a red-robed figure who speaks to you 1 n a su ue orbs was forgotten. Too many were content with tone. "There is a task that needs to _be done," their lot and power of the present and did not look murmurs the mage, "which is I~ the service of the forward into the future. And now, disturbing news Thorsz. It is fu I I of hardsh 1 ps and d~ngers, but Indeed has deve I oped. your rewards and renown w i I I be accord 1 ng I Y great. "The I and surrounding the rea I ms of the Thorsz Wi II you accept this bidding?" has become darker, more foreboding, and more With a silent nod you agree. dangerous. One in five patrols of the border guard "Good," mutters the wizard. "Here 1 s a to~en to returns with injury, or not at al I. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Gatehouse Gazette ISSUE 9 NOV ‘09 ISSN 1879-5676

Gatehouse Gazette ISSUE 9 NOV ‘09 ISSN 1879-5676 BEAUtIFUl Industry EMRE TURHAL ISSUE 8 Gatehouse Gazette SEP ‘09 CONTENTS The Gatehouse Gazette is an FEATURES online magazine in publication Loving the Factory, too 3 since July 2008, dedicated to the Industry and machines in steampunk and dieselpunk. speculative fiction genres of 4 steampunk and dieselpunk. Alchemy for Mystery Interview with Carol McCleary, author of The Alchemy of Murder The Flying Scotsman 8 Not a man with wings but a champion of the steam railway. Start up the Big Machines 16 The industrialization of Britain, Germany and France compared. The Asylum 19 Thoughts on the recent Lincoln, England steampunk convivial. COLUMNS REVIEWS Dieselpunk Season 12 Hilde Heyvaert’s The Steampunk Wardrobe . The Alchemy The Martini 15 of Murder 4 Craig B. Daniel’s The Liquor Cabinet . Boilerplate 7 Quatermass and the Pit 11 Guy Dampier’s last Quatermass review. Leviathan 10 Dieselpunk Online 6 The Invisible An overview of what’s new at the premier dieselpunk websites. Frontier 13 Casshern 18 ©2009 Gatehouse Gazette . All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Gatehouse Gazette . Published every two months by The Gatehouse . Contact the editor at [email protected]. PAGE 2 ISSUE 8 Gatehouse Gazette SEP ‘09 EDITORIAL LOVING THE NICK OTTENS FACTORY, TOO THERE ARE STARK AND UNDENIABLE DIFFERENCES dieselpunk, more distinctly informed b y cyberpunk between the mindsets of steampunk and dieselpunk in sensibilities, is more likely to become a dystopia than its spite of the close bonds between both genres and those steampunk counterpart. -

Golden Fantasy: an Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific Nu Iversity

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 3rd, 2016 Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Morrison, Zechariah James, "Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing" (2016). Honors Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/50 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. Golden Fantasy By Zechariah James Morrison Faculty Advisor, Owen Ewald Second Reader, Doug Thorpe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2016 2 Walk into any bookstore and you can easily find a section with the title “Fantasy” hoisted above it, and you would probably find the greater half of the books there to be full of vast rural landscapes, hackneyed elves, made-up Latinate or Greek words, and a small-town hero, (usually male) destined to stop a physically absent overlord associated with darkness, nihilism, or/and industrialization. With this predictability in mind, critics have condemned fantasy as escapist, childish, fake, and dependent upon familiar tropes. Many a great fantasy author, such as the giants Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others, has recognized this, and either agreed or disagreed as the particulars are debated. -

Defining Fantasy

1 DEFINING FANTASY by Steven S. Long This article is my take on what makes a story Fantasy, the major elements that tend to appear in Fantasy, and perhaps most importantly what the different subgenres of Fantasy are (and what distinguishes them). I’ve adapted it from Chapter One of my book Fantasy Hero, available from Hero Games at www.herogames.com, by eliminating or changing most (but not all) references to gaming and gamers. My insights on Fantasy may not be new or revelatory, but hopefully they at least establish a common ground for discussion. I often find that when people talk about Fantasy they run into trouble right away because they don’t define their terms. A person will use the term “Swords and Sorcery” or “Epic Fantasy” without explaining what he means by that. Since other people may interpret those terms differently, this leads to confusion on the part of the reader, misunderstandings, and all sorts of other frustrating nonsense. So I’m going to define my terms right off the bat. When I say a story is a Swords and Sorcery story, you can be sure that it falls within the general definitions and tropes discussed below. The same goes for Epic Fantasy or any other type of Fantasy tale. Please note that my goal here isn’t necessarily to persuade anyone to agree with me — I hope you will, but that’s not the point. What I call “Epic Fantasy” you may refer to as “Heroic Fantasy” or “Quest Fantasy” or “High Fantasy.” I don’t really care. -

Exploring Trauma Through Fantasy

IN-BETWEEN WORLDS: EXPLORING TRAUMA THROUGH FANTASY Amber Leigh Francine Shields A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2018 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/16004 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4 Abstract While fantasy as a genre is often dismissed as frivolous and inappropriate, it is highly relevant in representing and working through trauma. The fantasy genre presents spectators with images of the unsettled and unresolved, taking them on a journey through a world in which the familiar is rendered unfamiliar. It positions itself as an in-between, while the consequential disturbance of recognized world orders lends this genre to relating stories of trauma themselves characterized by hauntings, disputed memories, and irresolution. Through an examination of films from around the world and their depictions of individual and collective traumas through the fantastic, this thesis outlines how fantasy succeeds in representing and challenging histories of violence, silence, and irresolution. Further, it also examines how the genre itself is transformed in relating stories that are not yet resolved. While analysing the modes in which the fantasy genre mediates and intercedes trauma narratives, this research contributes to a wider recognition of an understudied and underestimated genre, as well as to discourses on how trauma is narrated and negotiated. -

Fantasy Films As a Postmodern Phenomenon A

FANTASY FILMS AS A POSTMODERN PHENOMENON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND DESIGN AND THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OF İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By İclal Alev Değim June 2011 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. İCLAL ALEV DEĞİM __________________________ ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Gürata (Advisor) I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Dilek Kaya Mutlu I certify that I have read this thesis and that in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________________ Dr. Özlem Savaş Approved by the Graduate School of Fine Arts ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Bülent Özgüç Director of the Graduate School of Fine Arts iii ABSTRACT FANTASY FILMS AS A POSTMODERN PHENOMENON İclal Alev Değim M.A. in Media and Visual Studies Advisor: Assist. Prof. -

Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy Kimberly Wickham University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Wickham, Kimberly, "Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 716. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/716 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUESTING FEMINISM: NARRATIVE TENSIONS AND MAGICAL WOMEN IN MODERN FANTASY BY KIMBERLY WICKHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF KIMBERLY WICKHAM APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Carolyn Betensky Robert Widell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. This assumption prevents Epic Fantasy works from achieving wide critical acceptance resulting in an under-analyzed and under-appreciated genre of literature. While some early works do follow the same narrative path as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Epic Fantasy has long challenged and reworked these narratives and character tropes. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. -

Gendered Quest in Recent Hungarian Fantasy Films.” Hungarian Cultural Studies

Benczik, Vera. “Gendered Quest in Recent Hungarian Fantasy Films.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 12 (2019) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2019.365 Gendered Quest in Recent Hungarian Fantasy Films Vera Benczik Abstract: Although the fantastic in print looks back upon a tradition of commenting on issues of race and gender, films that use the mode tend to be more conservative in their approach to subverting the patriarchal script, that is, the tendency of patriarchal society prescribing certain normative behaviors based on gender while punishing deviations from these norms. While this is especially true for blockbuster movies, independent filmmaking has come to appreciate the subversive potential of fantasy. The present study will scrutinize the fantastic as a storytelling mechanism in recent Hungarian cinema, with special emphasis on the uses of the quest formula and its intersections with gender scripts in the films Hurok [‘Loop’] (2016), and Liza, a rókatündér [‘Liza, the Fox-Fairy’] (2015). Keywords: coming-of-age narratives, redemptive narratives, “Groundhog Day” narrative template, female quest vs. male quest, the quest in fantasy/science fiction narratives, gendered quest, the fantastic in Hungarian filmmaking Biography: Vera Benczik is Senior Assistant Professor at the Department of American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, where she teaches courses on American and Canadian literature, science fiction and popular culture, with research interests mainly in the field of science fiction. Her current projects focus on the spatial discourse of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic science fiction narratives and the use of place and space in Margaret Atwood’s dystopian fiction. -

Myth, Mythopoeia and High Fantasy in Contemporary Indian Novels

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.7.Issue 3. 2019 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (July-Sept.) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE MYTH, MYTHOPOEIA AND HIGH FANTASY IN CONTEMPORARY INDIAN NOVELS Dr. SAMIR THAKUR1, Dr. SAVITA SINGH2, SHRADDHA SHARMA3 1Principal, RITEE College of Management Raipur (C.G.) 2Asst. Professor Department of English, Govt. NPG College of Science Raipur (C.G.) 3Research Scholar, Pt.Ravishankar Shukla Univercity, Raipur (C.G) doi: doi.org/10.33329/rjelal.73.235 ABSTRACT Myths are important to highlight the origin of world to society. Indian mythology and its innumerable sections have permanent influence on Indian literature as a whole, which can be considered a literary genre itself. Mythology in the Indian context encloses all-inclusive subject, to which everybody wants to be a part of life. Keywords – Myth, mythopoeia, Contemporary Indian novels . From the Greek mythos, myth means story mythology is like Chinese whispers. A story, told and or word. Mythology is the study of myth. As stories retold over generations, develops its own sub-plots, myths articulate how characters undergo or enact an introduces new characters and relatable events and ordered sequence of events. The term myth has changes perspectives according to the storyteller. come to refer to a certain genre of stories that share “Myth, history, and the contemporary – all characteristics that make this genre distinctly become part of the same chronological sequence; different from other genres of oral narratives, such as one is not distinguished from another; the passage legends and folktales. -

Rhetorics of the Fantastic: Re-Examining Fantasy As Action, Object, and Experience

Rhetorics of the Fantastic: Re-Examining Fantasy as Action, Object, and Experience Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Rick, David Wesley Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 15:03:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631281 RHETORICS OF THE FANTASTIC: RE-EXAMINING FANTASY AS ACTION, OBJECT, AND EXPERIENCE by David W. Rick __________________________ Copyright © David W. Rick 2019 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 Rick 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: David W. Rick Rick 4 Acknowledgments Since I began my program at the University of Arizona, I have been supported in innumerable ways by many dedicated people. Dr. Ken McAllister has been a mentor beyond all my expectations and has offered, in addition to advising, no end of encouragement and inspiration. -

The Stages of the Hero's Journey All Stories Consist of Common Structural Elements of Stages Found Universally in Myths, Fairy Tales, Dreams, and Movies

Excepts from Myth and the Movies, Stuart Voytilla1 Foreword By Christopher Vogler … Among students of myth like Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade, Theodore Gaster, and Heinrich Zimmer, the work of a man named Joseph Campbell has particular relevance for our quest. He hammered out a mighty link of the chain, a set of observations known as The Hero’s Journey. In books like The Hero with a Thousand Faces, The Power of Myth, and The Inner Reaches of Outer Space, Campbell reported on the synthesis he found while comparing the myths and legends of many cultures. The Hero’s Journey was his all-embracing metaphor for the deep inner journey of transformation that heroes in every time and place seem to share, a path that leads them through great movements of separation, descent, ordeal, and return. In reaction to Campbell’s work, a man named George Lucas composed what many have called a myth for our times - the Star War series, in which young heroes of a highly technological civilization confront the same demons, trials, and wonders as the heroes of old. ... The Stages of the Hero's Journey All stories consist of common structural elements of Stages found universally in myths, fairy tales, dreams, and movies. These twelve Stages compose the Hero's Journey. What follows is a simple overview of each Stage, illustrating basic characteristics and functions. Use it as a quick-reference guide as you explore the genre and movie analyses. Since it cannot provide all of Christopher Vogler's insights upon which it was based, I recommend you refer to his book, The Writer's Journey, for a much more thorough evaluation.