Re-Calibrating Steampunk London: Heterotopia and Spatial Imaginaries in Assassins Creed: Syndicate and the Order 1886

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk Marcus Janni Pivato Many people seem to think that William Gibson invented The cyberpunk genre in 1984, but in fact the cyberpunk aesthetic was alive well before Neuromancer (1984). For example, in my opinion, Ridley Scott's 1982 movie, Blade Runner, captures the quintessence of the cyberpunk aesthetic: a juxtaposition of high technology with social decay as a troubling allegory of the relationship between humanity and machines ---in particular, artificially intelligent machines. I believe the aesthetic of the movie originates from Scott's own vision, because I didn't really find it in the Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), upon which the movie is (very loosely) based. Neuromancer made a big splash not because it was the "first" cyberpunk novel, but rather, because it perfectly captured the Zeitgeist of anxiety and wonder that prevailed at the dawning of the present era of globalized economics, digital telecommunications, and exponential technological progress --things which we now take for granted but which, in the early 1980s were still new and frightening. For example, Gibson's novels exhibit a fascination with the "Japanification" of Western culture --then a major concern, but now a forgotten and laughable anxiety. This is also visible in the futuristic Los Angeles of Scott’s Blade Runner. Another early cyberpunk author is K.W. Jeter, whose imaginative and disturbing novels Dr. Adder (1984) and The Glass Hammer (1985) exemplify the dark underside of the genre. Some people also identify Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling as progenitors of cyberpunk. -

Citizen Cyborg.” Citizen a Groundbreaking Work of Social Commentary, Citizen Cyborg Artificial Intelligence, Nanotechnology, and Genetic Engineering —DR

hughes (continued from front flap) $26.95 US ADVANCE PRAISE FOR ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE NANOTECHNOLOGY GENETIC ENGINEERING MEDICAL ETHICS INVITRO FERTILIZATION STEM-CELL RESEARCH $37.95 CAN citizen LIFE EXTENSION GENETIC PATENTS HUMAN GENETIC ENGINEERING CLONING SEX SELECTION ASSISTED SUICIDE UNIVERSAL HEALTHCARE human genetic engineering, sex selection, drugs, and assisted In the next fifty years, life spans will extend well beyond a century. suicide—and concludes with a concrete political agenda for pro- cyborg Our senses and cognition will be enhanced. We will have greater technology progressives, including expanding and deepening control over our emotions and memory. Our bodies and brains “A challenging and provocative look at the intersection of human self-modification and human rights, reforming genetic patent laws, and providing SOCIETIES MUST RESPOND TO THE REDESIGNED HUMAN OF FUTURE WHY DEMOCRATIC will be surrounded by and merged with computer power. The limits political governance. Everyone wondering how society will be able to handle the coming citizen everyone with healthcare and a basic guaranteed income. of the human body will be transcended, as technologies such as possibilities of A.I. and genomics should read Citizen Cyborg.” citizen A groundbreaking work of social commentary, Citizen Cyborg artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and genetic engineering —DR. GREGORY STOCK, author of Redesigning Humans illuminates the technologies that are pushing the boundaries of converge and accelerate. With them, we will redesign ourselves and humanness—and the debate that may determine the future of the our children into varieties of posthumanity. “A powerful indictment of the anti-rationalist attitudes that are dominating our national human race itself. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Children Entering Fourth Grade ~

New Canaan Public Schools New Canaan, Connecticut ~ Summer Reading 2018 ~ Children Entering Fourth Grade ~ 2018 Newbery Medal Winner: Hello Universe By Erin Entrada Kelly Websites for more ideas: http://booksforkidsblog.blogspot.com (A retired librarian’s excellent children’s book blog) https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/reading-lists/childrens- choices/childrens-choices-reading-list-2018.pdf Children’s Choice Awards https://www.bankstreet.edu/center-childrens-literature/childrens-book-committee/best- books-year/2018-edition/ Bank Street College Book Recommendations (All suggested titles are for reading aloud and/or reading independently.) Revised by Joanne Shulman, Language Arts Coordinator joanne,[email protected] New and Noteworthy (Reviews quoted from amazon.com) Word of Mouse by James Patterson “…a long tradition of clever mice who accomplish great things.” Fish in a Tree by Lynda Mallaly Hunt “Fans of R.J. Palacio’s Wonder will appreciate this feel-good story of friendship and unconventional smarts.”—Kirkus Reviews Secret Sisters of the Salty Seas by Lynne Rae Perkins “Perkins’ charming black-and-white illustrations are matched by gentle, evocative language that sparkles like summer sunlight on the sea…The novel’s themes of family, friendship, growing up and trying new things are a perfect fit for Perkins’ middle grade audience.”—Book Page Dash (Dogs of World War II) by Kirby Larson “Historical fiction at its best.”—School Library Journal The Penderwicks at Last by Jean Birdsall “The finale you’ve all been -

THESIS ANXIETIES and ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING the POP CULTURE GYNOID Submitted by Carly Fabian Department of Communicati

THESIS ANXIETIES AND ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING THE POP CULTURE GYNOID Submitted by Carly Fabian Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2018 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Katie L. Gibson Kit Hughes Kristina Quynn Copyright by Carly Leilani Fabian 2018 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ANXIETIES AND ARTIFICIAL WOMEN: DISASSEMBLING THE POP CULTURE GYNOID This thesis analyzes the cultural meanings of the feminine-presenting robot, or gynoid, in three popular sci-fi texts: The Stepford Wives (1975), Ex Machina (2013), and Westworld (2017). Centralizing a critical feminist rhetorical approach, this thesis outlines the symbolic meaning of gynoids as representing cultural anxieties about women and technology historically and in each case study. This thesis draws from rhetorical analyses of media, sci-fi studies, and previously articulated meanings of the gynoid in order to discern how each text interacts with the gendered and technological concerns it presents. The author assesses how the text equips—or fails to equip—the public audience with motives for addressing those concerns. Prior to analysis, each chapter synthesizes popular and scholarly criticisms of the film or series and interacts with their temporal contexts. Each chapter unearths a unique interaction with the meanings of gynoid: The Stepford Wives performs necrophilic fetishism to alleviate anxieties about the Women’s Liberation Movement; Ex Machina redirects technological anxieties towards the surveilling practices of tech industries, simultaneously punishing exploitive masculine fantasies; Westworld utilizes fantasies and anxieties cyclically in order to maximize its serial potential and appeal to impulses of its viewership, ultimately prescribing a rhetorical placebo. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Modern Mythopoeia &The Construction of Fictional Futures In

Modern Mythopoeia & The Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904 2 Modern Mythopoeia & the Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Diana Simpson Hernandez MA Design Products Royal College of Art October 2012 Word Count: 10,459 3 INTRODUCTION: ON MYTH 10 SLEEPWALKERS 22 A PRECOG DREAM? 34 CONCLUSION: THE SLEEPER HAS AWAKEN 45 APPENDIX 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 90 4 Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904. Available from: <http://culturepotion.blogspot.co.uk/2010/08/witches- and-witchcraft-in-art-history.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 2. Evidence Dolls. Dunne and Raby. 2005. Available from: <http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/projects/69/0> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 3. Slave City-cradle to cradle. Atelier Van Lieshout. 2009. Available from: <http://www.designboom.com/weblog/cat/8/view/7862/atelier-van- lieshout-slave-city-cradle-to-cradle.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 4. Der Jude. 1943. Hans Schweitzer. Available from: <http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/posters2.htm> [accessed 15 September 2012] Figure 5. Lascaux cave painting depicting the Seven Sisters constellation. Available from: <http://madamepickwickartblog.com/2011/05/lascaux- and-intimate-with-the-godsbackstage-pass-only/> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 6. Map Presbiteri Johannis, Sive, Abissinorum Imperii Descriptio by Ortelius. Antwerp, 1573. Available from: <http://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/9021?view=print > [accessed 30 May 2012] 5 Figure 7. Mercator projection of the world between 82°S and 82°N. Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercator_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 8. The Gall-Peters projection of the world map Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gall–Peters_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 9. -

The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Leeds Beckett Repository The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture Professor Karl Spracklen (Leeds Metropolitan University, UK) and Beverley Spracklen (Independent Scholar) Lead Author Contact Details: Professor Karl Spracklen Carnegie Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QU 44 (0)113 812 3608 [email protected] Abstract From counter culture to subculture to the ubiquity of every black-clad wannabe vampire hanging around the centre of Western cities, Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture. The music’s cultural terrain has been extensively mapped in the first decade of this century. In this paper we examine the phenomenon of the Whitby Goth Weekend, a modern Goth music festival, which has contributed to (and has been altered by) the heritage tourism marketing of Whitby as the holiday resort of Dracula (the place where Bram Stoker imagined the Vampire Count arriving one dark and stormy night). We examine marketing literature and websites that sell Whitby as a spooky town, and suggest that this strategy has driven the success of the Goth festival. We explore the development of the festival and the politics of its ownership, and its increasing visibility as a mainstream tourist destination for those who want to dress up for the weekend. By interviewing Goths from the north of England, we suggest that the mainstreaming of the festival has led to it becoming less attractive to those more established, older Goths who see the subculture’s authenticity as being rooted in the post-punk era, and who believe Goth subculture should be something one lives full-time. -

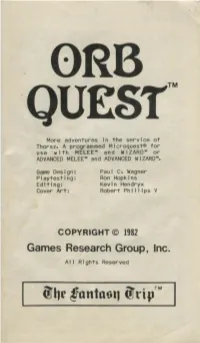

ORB QUEST™ Is a Programmed Adventure for the Instruction, It W I 11 Give You Information and FANTASY TRIP™ Game System

0RB QUEST™ More adventures in the service of Thorsz. A programmed Microquest® for use with ME LEE'" and WIZARD'" or ADVANCED MELEE'" and ADVANCED WIZARD'". Game Design: Paul c. Wagner Playtesting: Ron Hopkins Editing: Kevin Hendryx Cover Art: Robert Phillips V COPYRIGHT© 1982 Games Research Group, Inc. Al I Rights Reserved 3 2 from agai~ Enough prospered, however, to establish INTRODUCTION the base of the kingdom and dynasty of the Thorsz as it now stands. During evening rounds outside the w i. zard's "With time and the excess of luxuries brought quarters at the Thorsz's pa I ace, you are. deta 1 n~~ b~ about by these successes, the fate of the ear I i er a red-robed figure who speaks to you 1 n a su ue orbs was forgotten. Too many were content with tone. "There is a task that needs to _be done," their lot and power of the present and did not look murmurs the mage, "which is I~ the service of the forward into the future. And now, disturbing news Thorsz. It is fu I I of hardsh 1 ps and d~ngers, but Indeed has deve I oped. your rewards and renown w i I I be accord 1 ng I Y great. "The I and surrounding the rea I ms of the Thorsz Wi II you accept this bidding?" has become darker, more foreboding, and more With a silent nod you agree. dangerous. One in five patrols of the border guard "Good," mutters the wizard. "Here 1 s a to~en to returns with injury, or not at al I. -

Blade Runner and the Right to Life Eli Park Sorensen

Blade Runner and the Right to Life Eli Park Sorensen Trans-Humanities Journal, Volume 8, Number 3, October 2015, pp. 111-129 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/trh.2015.0012 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/635253/summary [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] Blade Runner and the Right to Life Eli Park SORENSEN (Seoul National University) Ⅰ. Introduction One of the most debated issues in connection with Ridley Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece Blade Runner (1982) is whether Deckard — the protagonist, played by Harrison Ford — is a replicant or not. Allegedly, Ford was strongly opposed to Scott’s decision to include the famous unicorn scene in the film, which apparently confirms that Deckard — like Rachael — possesses “implants,” synthetic memories; a scene anticipating the film’s ending, during which Deckard finds an origami unicorn left by detective Gaff, who thus reveals that he knows about Deckard’s real identity — that he is in fact a replicant (Sammon 362). In this article, I suggest that although much of the scholarship and criticism on Blade Runner tends to focus on this particular issue, it nonetheless remains one of the least interesting aspects of the film. Or, to put it differently, whether Deckard is a replicant is a question whose real purpose rather seems to be covering a far more traumatic issue, which Michel Foucault in the first volume of History of Sexuality addresses thus: “The ‘right’ to life, to one’s body, to health, to happiness, to the satisfactions of needs, and beyond all the oppressions or ‘alienations,’ the ‘right’ to rediscover what one is and all that one can be” (145).